The increasing incidence of acquired cognitive impairment, whether due to neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or vascular disease, means that it is increasingly likely for an eye care professional to have dealings with patients with this impairment.

Recent Events

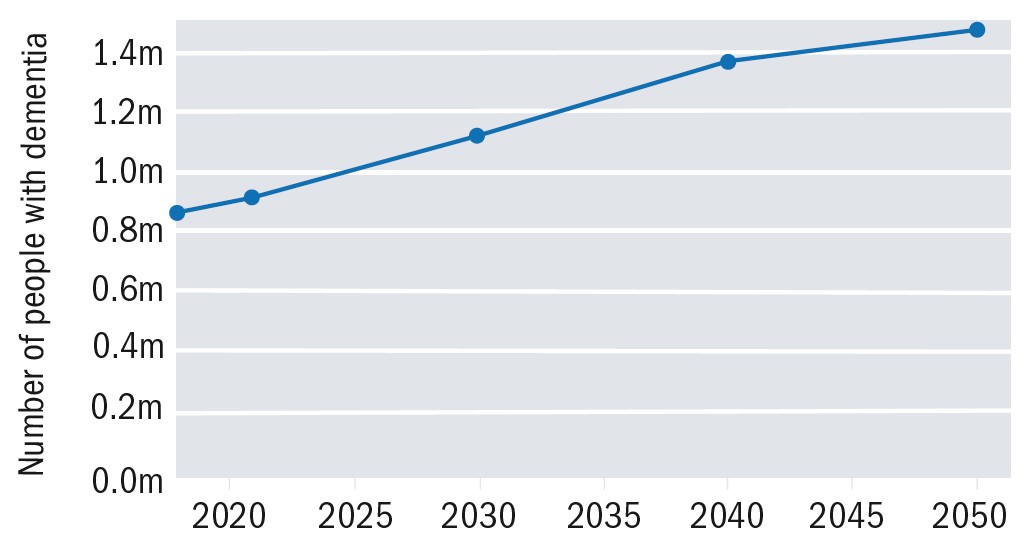

Since I last discussed this issue in this publication (see Optician 08.06.18), there have been two major influences upon the extent and nature of dementia in the UK. The first was, as predicted in my previous discussion, the incidence (that is, the prevalence over a given time) of dementia in the UK has increased, and this increase is set to continue in the coming years (figure 1).

Figure 1: Increasing prevalence of UK dementia predicted up to 20501

Figure 1: Increasing prevalence of UK dementia predicted up to 20501

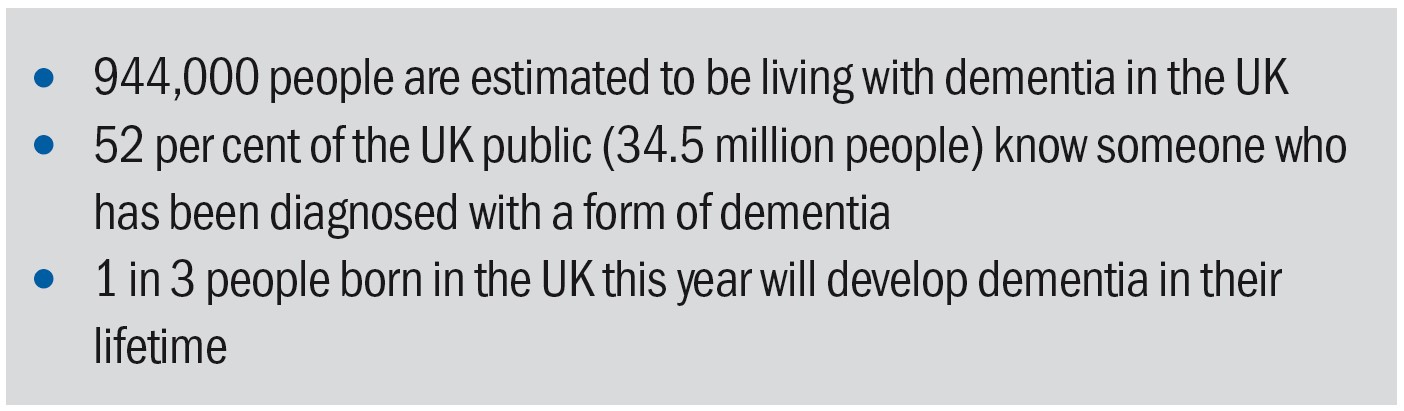

The need to provide appropriate healthcare support for people living with dementia has become more apparent as our population age rises, and the number of people in the UK currently diagnosed with a form of dementia is now 944,000 (up from the 850,000 just three years ago).1 See Table 1 for an overview of the latest statistics.

Table 1: Statistics about dementia in the UK in 20221

Table 1: Statistics about dementia in the UK in 20221

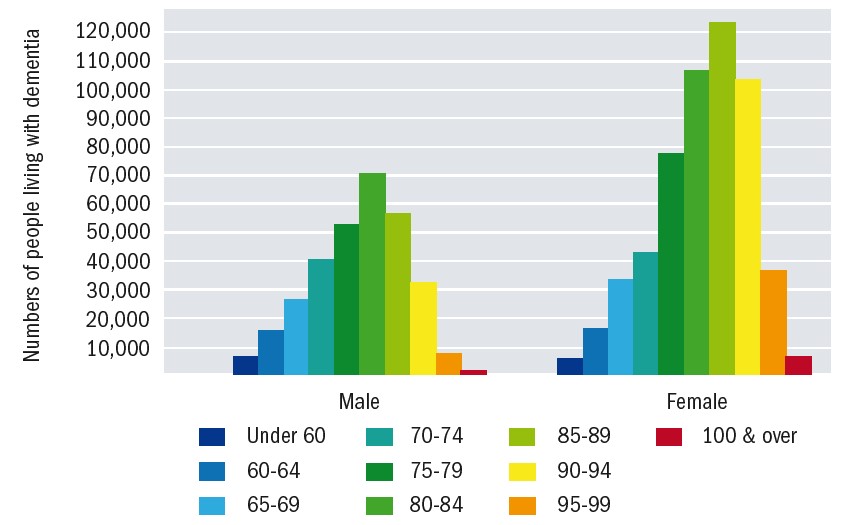

There is also a shift in emphasis away from the perception that dementia only impacts on people in the later stages of life. There is currently an estimated 42,325 people in the UK diagnosed with young onset dementia, which represents over 5% of the total number with dementia.2 This re-evaluation of dementia is important to consider, and not just from perspective of those working in the care and medical professions who will increasingly be coming across people living with dementia. It is also important for businesses and employers who will need to accommodate the likelihood that their employees may develop dementia before retirement age. For the majority of dementia, the prevalence reflects life expectancy (figure 2). There is a clear female predisposition, as might be expected by the longer life expectancy, but this shift is also likely to be influenced by other physiological and societal factors.

Figure 2: Dementia prevalence by age and gender1

Figure 2: Dementia prevalence by age and gender1

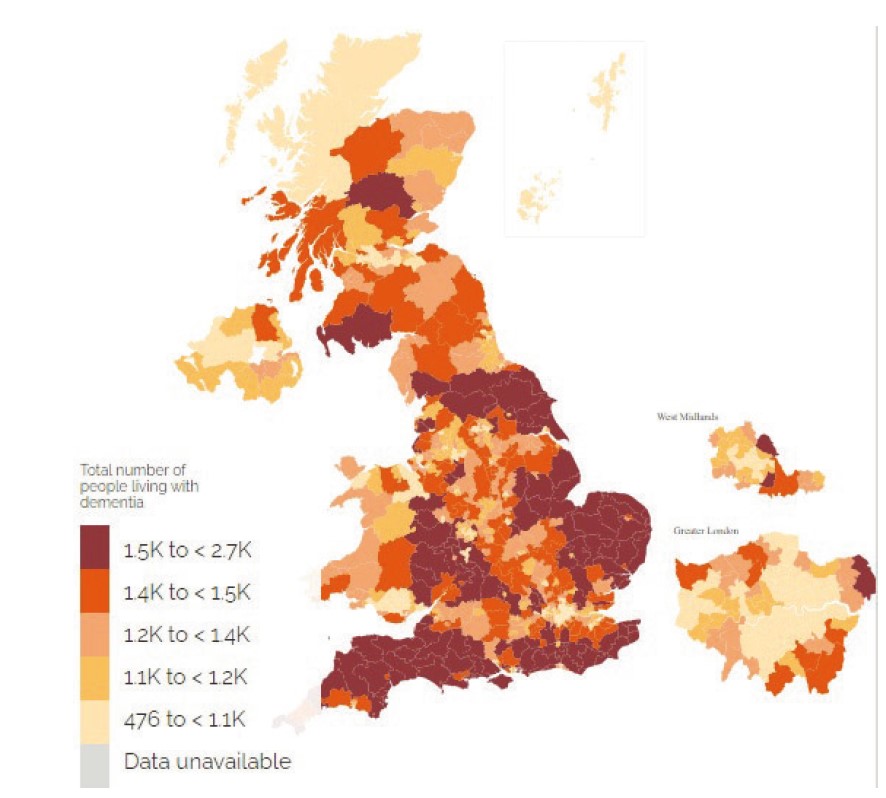

It is also worth noting the geographical distribution of dementia in the UK (figure 3). It can be seen that the areas with the highest concentration of dementia tend to be those of lower population density and are often rural. This has implications for both practitioners, in being able to predict the problems of their patient base, and also for the nature of care, especially in terms of accessibility to services.

Figure 3: Geographical distribution of dementia in the UK

Figure 3: Geographical distribution of dementia in the UK

The second major influence on health in all areas since my last report has been the less widely predicted global pandemic, an event that is taking its toll on all of our mental and physical states of well-being. This has limited access to health professionals, and so likely to have caused a number of delayed diagnoses. The Alzheimer’s Society reports that here has been a significant decrease in dementia diagnosis rates, from 67.6 per cent in February 2020 to 63.5 per cent in June 2020.3 The same report suggested that data from the lockdown period revealed a sharp drop in the number of referrals to memory services. There are usually, on average, 2,600 referrals from primary care to memory clinics per month, yet data from April 2020 showed only 84, May 435 and June 994. While referral rates are returning to the expected levels again, the obvious conclusion is that there is a significant backlog of care and that many people with dementia are likely to have ‘slipped through the net.’ As the Alzheimer’s Society states: ‘A sustained and proactive effort must be made to support access to a timely diagnosis.’

Another change foist upon us by the lockdown has been the rise in consultations, both clinical and social, via electronic means, either video or audio only. As we shall see, the lack of direct, face-to-face contact has a negative impact on the quality of information exchange with a dementia patient and limits the positive impact of any such exchange upon the patient. That said, the increased use of remote consultation does have some potential in future in improving contact networks and frequency of contact and, as such, is included in the key messages cited at the end of this article.

While the impact of the pandemic on people with dementia has been widely reported upon, for those charged with caring for people with dementia, the easing of lockdown restrictions may not make much of a difference, something that the charity Dementia UK has highlighted with their Lives on Hold campaign. Launched in 2020, this awareness campaign aims to show how life for carers of people living with dementia is similar to living in lockdown, often for many months or years. A sad fact remains that, as life begins to get back to a new kind of post-pandemic normal for most people, families living with dementia will see little change.4

For eye care professionals, these statistics have a number of implications. When access to health professionals is restricted in any way, it is often the primary care sector, especially in those areas where routine regular check-ups are the norm, such as optometry, dentistry, podiatry and so on, where the first suspicions of a cognitive decline might be detected. For this reason, all ECPs should be comfortable in recognising the possible early signs of dementia and become familiar with the care pathway available to their place of work.

Furthermore, it is worth remembering that ECPs should be aware of the Mental Capacity Act (2005), and be able to make a judgement as to whether a patient is in a position to be able to give informed consent for any procedure or recommended action.

In a major paper published in The Lancet in 2017, it was stated that ‘dementia is the greatest global challenge for health and social care in the 21st century’ and stressed that the responsibility of preventing dementia and improving the quality of life for carers lies with us all.5 ECPs are very much part of this.

What is dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term to describe a set of symptoms associated with an ongoing decline of brain functioning. Memory loss is the symptom most commonly associated with dementia however it is not always the first or more prominent symptom, other symptoms include:

- Communication difficulties

- Disorientation of time

- Place and person

- Mood swings

- Apathy and depression

- Lack of coordination or balance

- Visual perceptual difficulties and hallucinations

There is always a cognitive decline with dementia, which progresses at different rates for each individual. The two most common types of dementia are Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia, but there are numerous other types of dementia such as dementia with Lewy bodies, caused by tiny spherical protein deposits in the brain, or frontotemporal dementia, which tends to occur at a younger age, generally between the ages of 40 and 45, and which affects the part of the brain associated with empathy and executive function.

Although all forms of dementia exhibit similar symptoms, they often follow different patterns of decline. For example, with AD, the decline tends to be a steady downhill slope whereas, with vascular dementia, you might not notice any changes in someone’s behaviour for some time until a sudden deterioration, often triggered by a minor stroke. This is often described as a staircase pattern of decline.

The main drugs used to treat AD are the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine (used as monotherapies) or memantine (used when patients are intolerant to the pre-mentioned drugs or suffer from severe AD).6 These drugs are used because it is suggested that cognitive impairment in AD is the result of cholinergic synaptic dysfunction in the hippocampus and neocortex.

Mostly, the adverse effects of these drugs are systemic, ranging from drowsiness to urinary retention, constipation and hallucinations. Blurred vision has also been reported after treatment with these drugs. Nevertheless, as these drugs improve the blood flow at the brain level, and many patients with normal-tension glaucoma have been found to exhibit abnormal cerebral blood flow similar to patients with AD, it could be hypothesised that these drugs may have a beneficial effect for glaucoma patients. In addition, they also lower the IOP, even with oral intake.7 In addition, animal studies have also demonstrated that the drug galantamine protects retinal ganglion cell structure and function in a rat model of glaucoma.8 These effects need further investigation.9

There is no known cure for dementia, but the medication that can be taken by AD patients may help with memory loss and confusion, as well as improve concentration, motivation and assist with aspects of daily living such as cooking or shopping.

What does this mean for eye care practitioners?

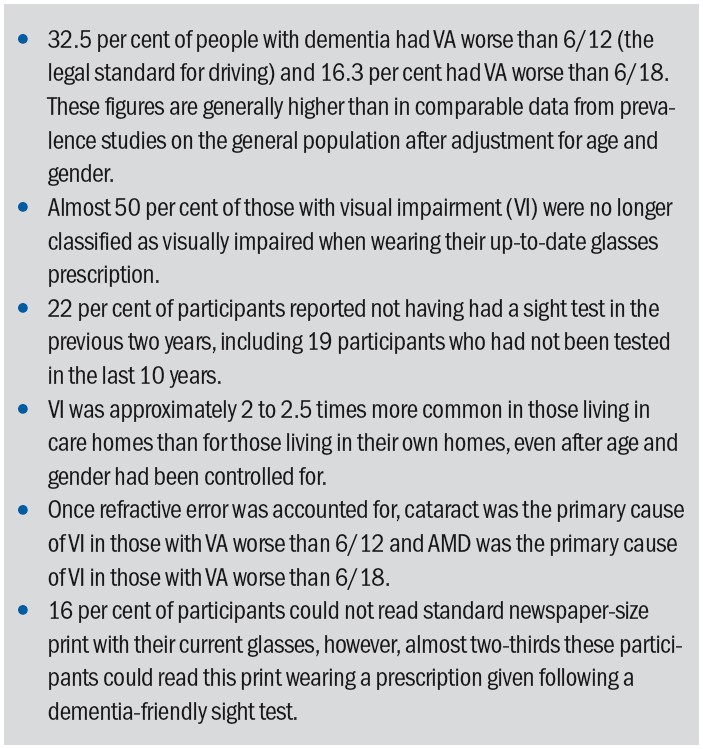

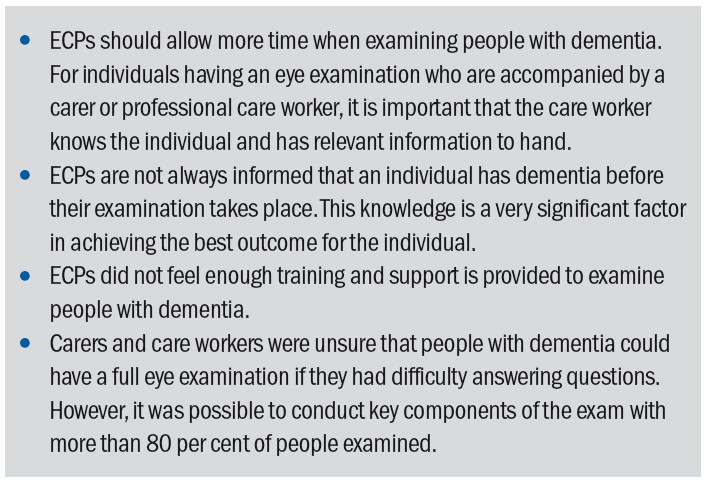

There are currently thought to be around 250,000 people living with dementia and sight loss in the UK. A major study, entitled the Prevalence of Visual Impairment in People with Dementia (PrOVIDe) study, found that ‘the prevalence of sight loss in people with dementia is higher than the overall population, and almost 50 per cent of those with sight loss were no longer classified as visually impaired when wearing the correctly prescribed glasses.’10 The PrOVIDe study, led by the College of Optometrists in association with universities and charitable organisations, aimed to measure the prevalence of a range of vision problems in people with dementia aged 60 to 89 years to determine the extent to which their vision conditions are undetected or inappropriately managed. The study’s key findings are highlighted in tables 2 and 3.

Table 2: Key findings of the PrOVIDe study

Table 2: Key findings of the PrOVIDe study

Table 3: Findings of the PrOVIDe study of particular relevance to eye care professionals

Table 3: Findings of the PrOVIDe study of particular relevance to eye care professionals

The RNIB encourages people with dementia to get regular eye checks because common side effects of dementia can be alleviated by low vision aids. Often symptoms of dementia, such as problems with balance or visual perception issues, are dismissed as dementia when they are actually caused by sight loss or treatable visual issues. Loss of vision causes someone with dementia to lose confidence in moving around spaces safely and often prevents them from carrying out familiar activities.

Accommodating for both dementia and sight loss can be harder than living with either condition on its own and causes loss of independence, increased confusion and disorientation. People with both conditions are also at a heightened risk of anxiety, depression, communication difficulties, low self-esteem, sleep disturbance and social isolation. The chances of developing dementia and the speed in which symptoms of dementia progress is exacerbated by social isolation. It is, therefore, vital that eye care professionals make every moment count. Remember, the trip to the ‘opticians’ might be the only social interaction an elderly patient will have that week.

Obstacles facing eye care professionals when treating dementia patients

Aggression and communication difficulties are some of the biggest difficulties facing eye care practitioners when treating someone with dementia. It is important to identify probable causes of these behaviours in order to make sure patients can get the appropriate treatment. Table 4 outlines possible causes of aggression.

Table 4: Possible triggers for aggressive behaviour

Table 4: Possible triggers for aggressive behaviour

Some symptoms, most commonly aggression, but also hallucination (Charles Bonnett syndrome) and symptoms caused by low vision, are often incorrectly ascribed to dementia. There is a persistent ideology that dementia causes aggression, or that there is a form of dementia that causes violent behaviour, but in most cases the aggression is caused by social factors (there are some exceptions). These social factors are wide and varied, and it is often the job of a family member, carer or healthcare professional to detect the cause of the problem. Aggression in dementia patients is usually caused by external factors such as temperature, noise or pain and should be taken as indicators of physical or psychological distress. Someone with dementia may not be able to locate the cause of their discomfit or might struggle to communicate that they are experiencing pain or confusion.

The RNIB produce an excellent document for patients with dementia, which is helpful both to them and any carers. Included are some key tips about how they may helps themselves with visual challenges. These include:

- Follow the three Cs: make sure glasses are always current, clean and correct

- Make sure glasses fit well

- Ensure good, even lighting to help reduce shadows

- Reduce the risk of trips and falls

- Use good colour contrast, especially for everyday activities

- Having plain backgrounds, for example for walls, can be more helpful than patterned

- When guiding the person indoors, give information about the people who are present and the environment

- Ensure any medication, especially eye drops are taken

Better communication and person-centred care

The first means of improving communication with dementia patients is to limit any environmental factors that could cause distress. Someone with dementia can find background noise, like televisions, radios or chatter, very distressing. Find a quiet well-lit place to carry out assessments, minimising outside distractions wherever possible.

Try to make the environment as dementia friendly as possible. This may include making small changes to your consultation rooms. These changes may include using contrasting colours, so the chairs are distinguishable from the floor, and avoid heavily patterned or shiny surfaces wherever possible because someone with dementia may have difficulties seeing things in three dimensions.

Someone with dementia may refuse or avoid entering a room because they think the floor looks wet or because, to them, it looks like there is a large hole in the ground. In a room with heavily patterned flooring, someone with dementia may be more prone to falls because the floor looks like it is covered in objects. They may even lean down to pick them up. Poor vision and issues with 3D perception can account for paranoia or delusions experienced by the patient, especially in poorly lit rooms. Table 5 summarises possible obstacles to good communication.

Table 5: Obstacles to good communication

Table 5: Obstacles to good communication

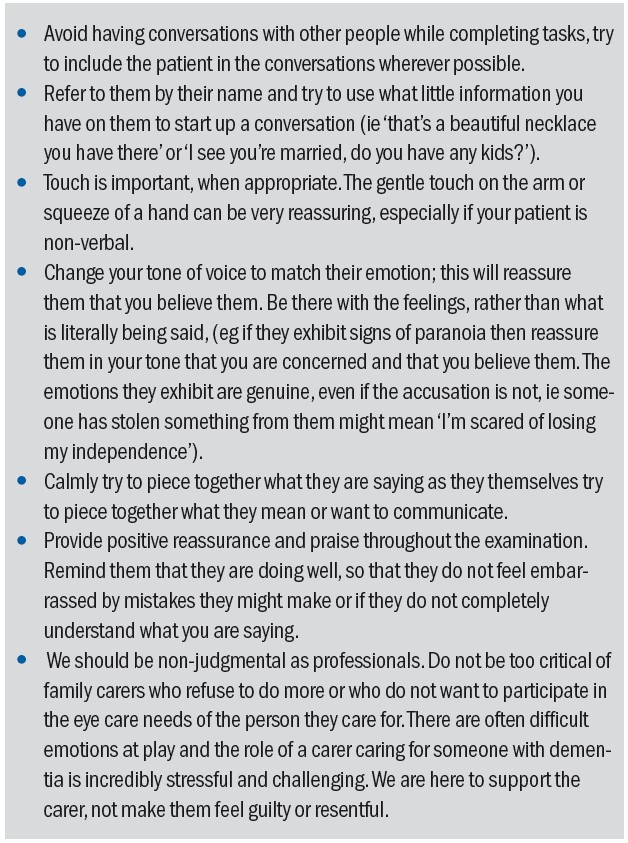

It is also useful for eye care practitioners to adapt their speech and body language to be more accommodating to someone with dementia. Improved communication and person-centred care largely involve considering what the person with dementia understands, is trying to say, and what they want, rather than being focused on completing a task. This involves both verbal and non-verbal communication skills.

Using a calm tone, maintaining eye contact and smiling are all very reassuring, especially if the patient is scared or confused. Try breaking down tasks or explanations into short, clear and simple instructions, and avoid giving too many choices at once. Take the time to repeat or simplify what you have already said and be patient, this will save you more time in the long run because you will avoid challenging behaviours. Sometimes people with dementia have difficulty relating words to objects and it can help showing them the object you are talking about, for example when asking them ‘would you like a drink?’ do so while showing them a mug or glass.

Reminiscence is one of the best tools we have for communicating with someone with dementia. Short-term memory is impaired in dementia patients, but long-term memory remains very acute for a long time, and when speaking with someone with dementia we often have to enter their timeline and reality. Someone with dementia may keep losing or refuse to wear their new glasses because they do not recognise them. It might be better, where possible, to fit old frames with new lenses or help carers choose new frames that are as similar to the patient’s old glasses as possible.

It might be helpful using older terminology or equipment that resembles older models, or using objects or language that is more familiar to them. Try to use what little information you might have about the person with dementia to encourage them to open up and talk about themselves. This will make them calmer and therefore make it easier to test their eyes, but also enables this brief eye examination to be a meaningful interaction.

One of the treatments currently used by memory doctors is Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST), which uses reminiscence, games and activities and group social interaction to stimulate brain activity and thus help slow down further cognitive decline. If appropriately utilised, even the shortest eye examinations can have positive results for dementia patients, or elderly patients who are more at risk of developing dementia. Studies have shown that social engagement can be an important mechanism for improving the quality of life among people with dementia.

If there is a carer present, then utilise their knowledge of the patient and work with them to ensure their loved one is calm and comfortable. Family carers are the most important resource available for people with dementia and consequently for healthcare professionals. Use their knowledge and experience to communicate effectively with your patient. However, do not leave the person with dementia out of the conversation, do not ignore them while talking to the carer and always include them in decisions about their care wherever possible. Avoid situations where the carer might be contradicting the patient (‘yes – I have been putting my eye drops in every day’), if this situation occurs try to provide the opportunity to speak briefly with the carer in private.

Table 6 summarises the various approaches to improving communication with a dementia patient.

Table 6: Tips on communication with a dementia patient

Table 6: Tips on communication with a dementia patient

Ten Key Points for the Future

The 2017 Lancet Commission report5 listed 10 key points worthy of consideration by all healthcare professionals with regard to dementia, its prevention, its detection and its management. These are worth repeating here.

- The number of people with dementia is increasing globally.

- Be ambitious about prevention; recommendations include the active treatment of hypertension in middle-aged (45 to 65 years) and older people (aged older than 65 years) without dementia to reduce dementia incidence. Interventions for other risk factors including more childhood education, exercise, maintaining social engagement, reducing smoking and management of hearing loss, depression, diabetes and obesity might have the potential to delay or prevent a third of dementia cases.

- Treatment of cognitive symptoms; to maximise cognition, people with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies should be offered cholinesterase inhibitors at all stages, or memantine for severe dementia. Cholinesterase inhibitors are not effective in mild cognitive impairment.

- Individualised care; effective dementia care spans medical, social and supportive care; it should be tailored to unique individual and cultural needs, preferences, and priorities and should incorporate support for family carers.

- Care for carers; family carers are at high risk of depression. Effective interventions will reduce the risk of depression, treat the symptoms, and should be made available.

- Plan for the future; people with dementia, and their families, value discussions about the future and decisions about possible attorneys to make decisions.

- Protect people with dementia; people with dementia and society require protection from possible risks of the condition, including self-neglect, vulnerability (including to exploitation), managing money, driving and so on. Risk assessment and management at all stages of the disease is essential, but it should be balanced against the person’s right to autonomy.

- Manage neuropsychiatric symptoms; management of the neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, including agitation, low mood or psychosis is usually psychological, social, and environmental, with pharmacological management reserved for individuals with more severe symptoms.

- Consider end of life; a third of older people die with dementia, so it is essential that professionals working in end-of-life care consider whether a patient has dementia, because they might be unable to make decisions about their care and treatment or express their needs and wishes.

- Technology; technological interventions have the potential to improve care delivery but should not replace social contact.

What help is available?

There is not currently a uniform body for dementia, but most local boroughs will have services or charities who can support both people living with dementia and their carers. If your patients exhibit any of the symptoms of dementia previously described, the procedure is to refer them to their GP who will do an initial cognitive assessment.

There are several different tests, but the most common ones used by GPs are the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG) or the Abbreviated mental test score (AMTS). Based upon the test scores, the GP will refer them to the local Memory Service for further cognitive assessments and brain scans. Once the diagnosis is in place, patients can access more support services, though again these vary from borough to borough.

Some London boroughs have established dementia hubs, which are information and signposting services that can answer most of your dementia-related questions (check out the Bromley Dementia Support Hub). There are also a lot of resources online. The Alzheimer’s Society has a whole wealth of information fact sheets and leaflets on dementia, varying from Understanding and supporting a person with dementia (524) to Sight, perception and hallucinations in dementia (527). These fact sheets are useful for anyone who wants to know more about dementia and are not restricted to dementia patients. Similarly, useful resources with more of a focus on dementia and sight loss are available from the RNIB website and well worth downloading.

Useful Resources

Charities such as Alzheimer’s Society, Age UK and Mind are stressing the importance of Wellbeing and trying to change the stigma surrounding dementia. Here are some important links for useful information and resource:

RNIB

- 0303 123 1999

- rnib.org.uk

Alzheimer’s Society

- 0300 222 1122

- alzheimers.org.uk

Vision UK

- visionuk.org.uk

Thomas Pocklington Trust

- pocklington-trust.org.uk

AgeUK

- 0800 678 1602

- ageuk.org.uk

Mind

- 0300 123 3393

- mind.org.uk

- Tallulah Harvey is formerly a liaison officer with the mental health charity MIND with responsibility for linking people with dementia with healthcare professionals and is now program manager for Fifteen Seconds, a technology and innovation festival.

References

- https://www.dementiastatistics.org (accessed January 2022)

- Prince, M et al (2014) Dementia UK: Update Second Edition report produced by King’s College London and the London School of Economics for the Alzheimer’s Society

- www.dementiauk.org/lives-on-hold (accessed January 2022)

- www.alzheimers.org.uk/news/2020-08-10/coronavirus-affecting-dementia-assessment-diagnosis

- Livingston G et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017, Dec 16;390(10113):2673-2734

- www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta217/chapter/1-Guidance

- Estermann S et al. Effect of oral donepezil on intraocular pressure in normotensive Alzheimer patients. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2006, 22(1),62–67

- Almasieh M et al. Structural and functional neuroprotection in glaucoma role of galantamine-mediated activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Cell Death & Disease, 2010, 1(2),e27

- Gherghel D. Ocular side effects of systemic drugs 3: Central nervous system agents. OPTICIAN, 22.05.20, pp20-23

- Bowen M, Edgar DF, Hancock B, et al. The Prevalence of Visual Impairment in People with Dementia (the PrOVIDe study): a cross-sectional study of people aged 60–89 years with dementia and qualitative exploration of individual, carer and professional perspectives. Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 4.21. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK374272/doi:10.3310/hsdr04210