Depending on the demographics of the local community, most community eye care professionals (ECPs) regularly encounter patients with 6/6 Snellen vision or better and a full visual field. Not every patient, however, reaches this perfect standard, even after full correction of the refractive error or after receiving treatment for their condition.

Vision may be reduced despite the best efforts of optometrists and ophthalmologists. Impaired vision can lead to impaired functioning, reduced independence and a lower quality of life (QoL). ECPs need to use their professional judgement to decide to what extent a patient’s visual impairment is affecting their day-to-day activities and ability to function as their patient may benefit from low vision services or they may be eligible for sight impairment (SI) or severe sight impairment (SSI) certification and subsequent registration.

For those patients who meet the eligibility criteria for certification, a referral to the hospital eye service may be warranted. How do community optometrists decide which patients need to be referred for vision impairment certification? How familiar are optometrists with the guidelines? Do optometrists actively discuss registration benefits with their patients? What visual functions are relevant in the context of certification? Are patients with sub-optimal vision routinely asked about their QoL? These questions are the focus of this article for which a survey was carried out among a small group of optometrists in the UK.

Background

Most patients with ocular vision impairment attend an eye department for diagnosis and treatment of their condition. Patients who receive treatment continue to have regular appointments and it is therefore reasonable to assume that it is the ophthalmologists’ responsibility to refer patients to the low vision clinic and to consider certification for sight impairment.

In practice, however, this does not always happen and patients could be attending an eye department for years before they are offered support. The author recently conducted a survey among ophthalmologists in Edinburgh which revealed that, at least in the hospital surveyed, the commonest barriers for offering certification were as follows:

- Lack of understanding of the benefits of registration

- Limited time in clinic

- Uncertainty about the best time to certify

It would appear ophthalmologists are often focused on treating the condition and that referral to low vision services or offering certification for sight impairment simply does not spring to mind during their busy clinics. Many patients attending the low vision clinic confirm they wished they had been referred or certified many years earlier.

One also has to remember that patients with conditions such as dry age-related macular degeneration are usually managed in the community and may never attend hospital eye services. In this case, it is the responsibility of the community optometrist to decide if a referral is warranted for certification of vision impairment or indeed for support from low vision services. Once this referral has been made, it is the consultant ophthalmologist’s responsibility to certify the patient.

Certification and Registration

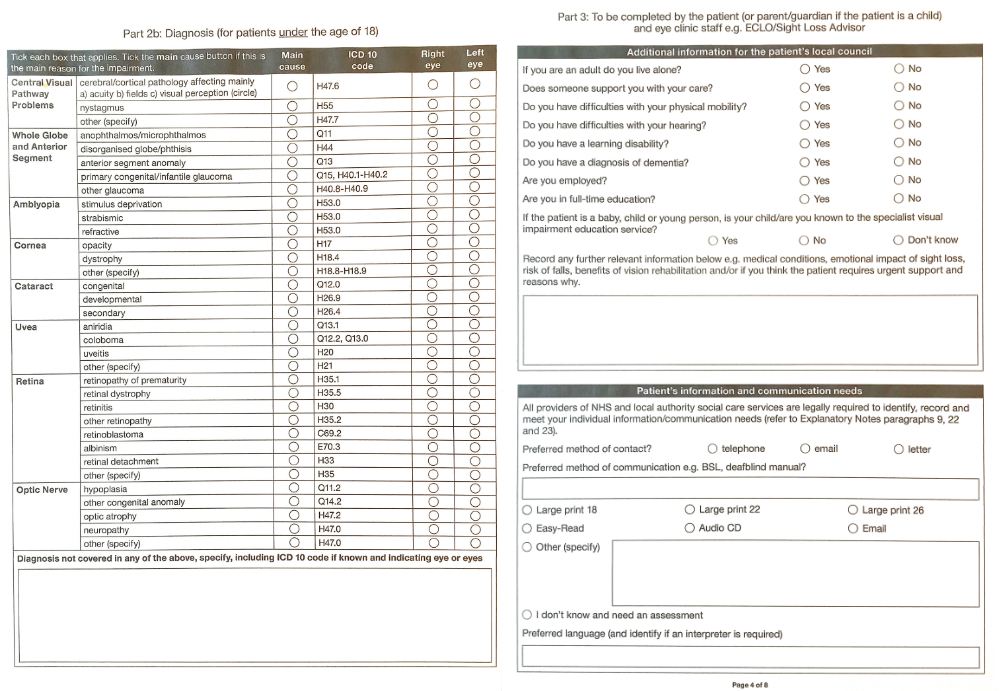

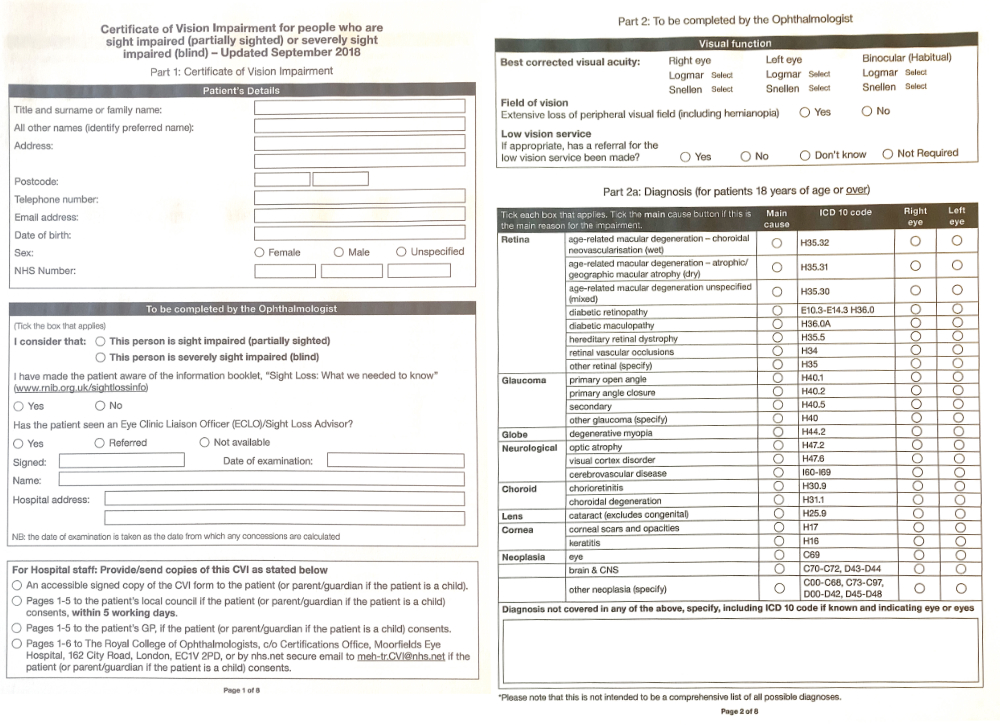

In England and Wales, certification can be completed online with a Certificate of Vision Impairment (CVI). In Scotland, a paper copy of the Certificate of Vision Impairment Scotland (CVI Scotland, formerly the BP1) form is completed and signed by the consultant ophthalmologist and the patient. In Northern Ireland, the CVI is called an A655. Figure 1 shows the first four pages of the CVI document.

This form is then passed on to the local authority (or the agency acting on their behalf) to process and update the register. According to the national standards of social care for visually impaired adults,1 patients should be contacted by social care within 10 working days of referral or receipt of their CVI. It then can take up to three months for the patient to receive their certificate of registration.

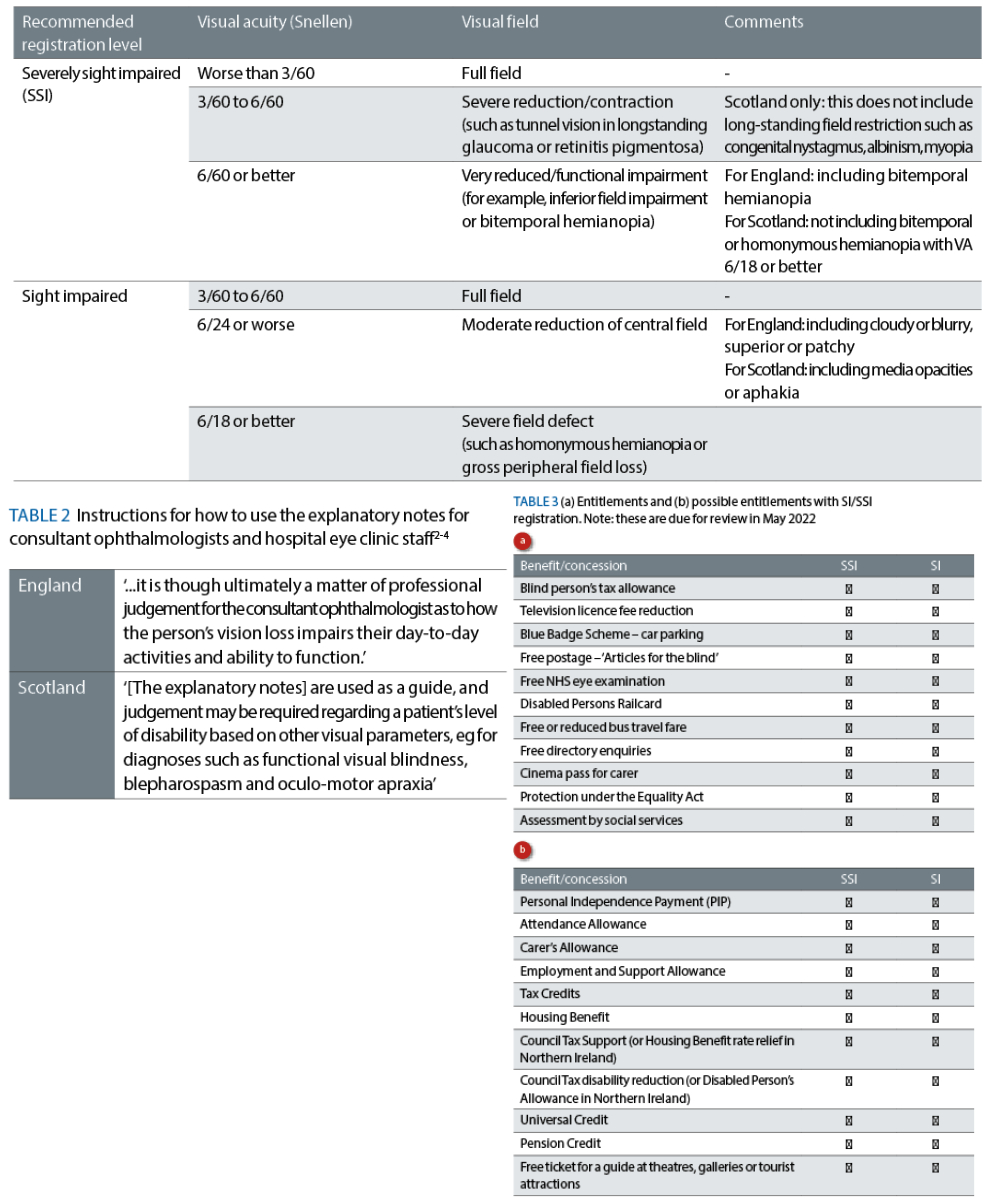

Deciding which patients are eligible for registration is not always straightforward and, therefore, the explanatory notes for consultant ophthalmologists and hospital eye clinic staff include guidance for certification in terms of visual acuity and visual field impairment (see table 1 and figure 2).2-4

Interestingly, there is no guidance in terms of contrast sensitivity. This is despite the evidence that contrast sensitivity is a strong indicator for experienced QoL.5-8 The visual function guidelines are not prescriptive.

However, as the focus should be on functional vision, the explanatory notes for consultant ophthalmologists and hospital eye clinic staff should be used as a guide. Each case should be assessed in the context of functional vision as illustrated in table 2 and an element of discretion needs to be introduced on a case-by-case basis.

Figure 1: A CVI form (February 2022). Part 1, top left, shows to whom copies are sent. Part 2, 2a and 2b, top right & bottom left, show diagnostic information for completion by an ophthalmologist. Part 3, bottom right, asks for further details of the impact of sight loss. The remaining pages (not shown here) include declaration of consent, ethnicity details and further information

Benefits of SI/SSI registration

The ultimate goal of sight impairment registration is to help patients remain as independent as possible and to facilitate access to services. Support is provided at an individual level, whereby a patient can claim benefits and receive practical support (see table 3). Vision impairment registration also benefits the wider community as the number of registrations informs local authorities about the needs of the population. For example, in areas with a high number of registered patients, traffic lights may be more readily adapted with beeping signals or tactile signals, such as rotating cones and tactile paving.

Current Awareness

The responsibility for initiating a discussion about vision impairment certification and registration benefits is a shared responsibility of all health care professionals; including ophthalmologists, optometrists and dispensing opticians. Do optometrists feel equipped to deal with this issue? What are some of the barriers for discussing this topic? Which factors are considered important when considering a referral for certification?

Two surveys were carried out among optometrists in January 2022, using Survey Monkey. Optometrists working in the community, as well as optometrists working in the hospital eye service, were invited to take part. A total of 14 optometrists completed the survey about understanding registration benefits. Of these optometrists, six worked in the hospital eye service and eight worked in community optometry.

Questions were asked about self-perceived knowledge of registration benefits, of the process of certification and registration and of certification criteria. A total of 13 optometrists completed the survey about clinical decision making. Of these optometrists, five worked in the hospital eye service and eight worked in community optometry. Questions were asked about the perceived relevance of visual function tests and other factors in the decision-making process.

Table 1: Guidelines for certification for England and Scotland2-4

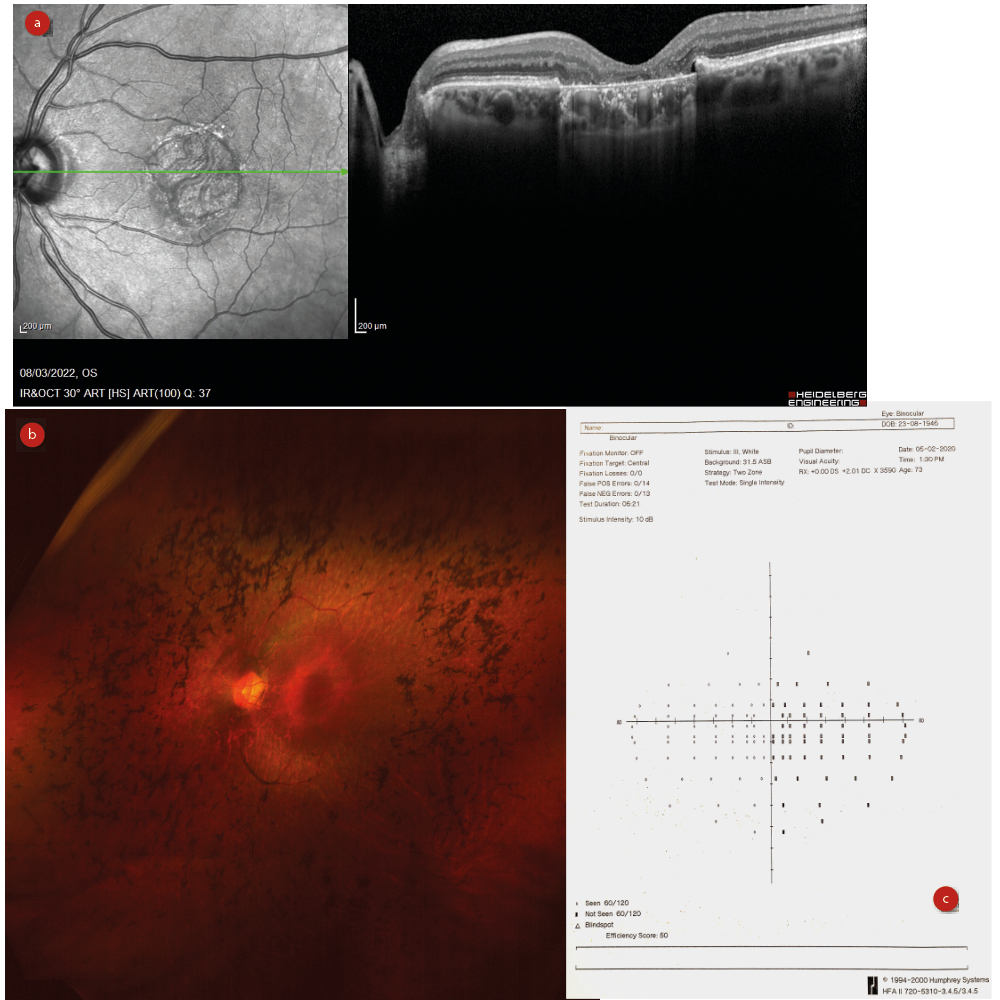

Figure 2: Registration eligibility depends upon loss of acuity, as with

(a) macular degeneration, or visual field contraction, as with (b) retinitis pigmentosa or (c) stroke

Referral frequency

Optometrists were asked how many patients they had referred for SI or SSI certification in the past year. Hospital optometrists made more referrals than community optometrists, with half of the hospital optometrists estimating more than 10 referrals in the past year. In the community, all optometrists estimated their referral totals for certification to be five or less in the same time period.

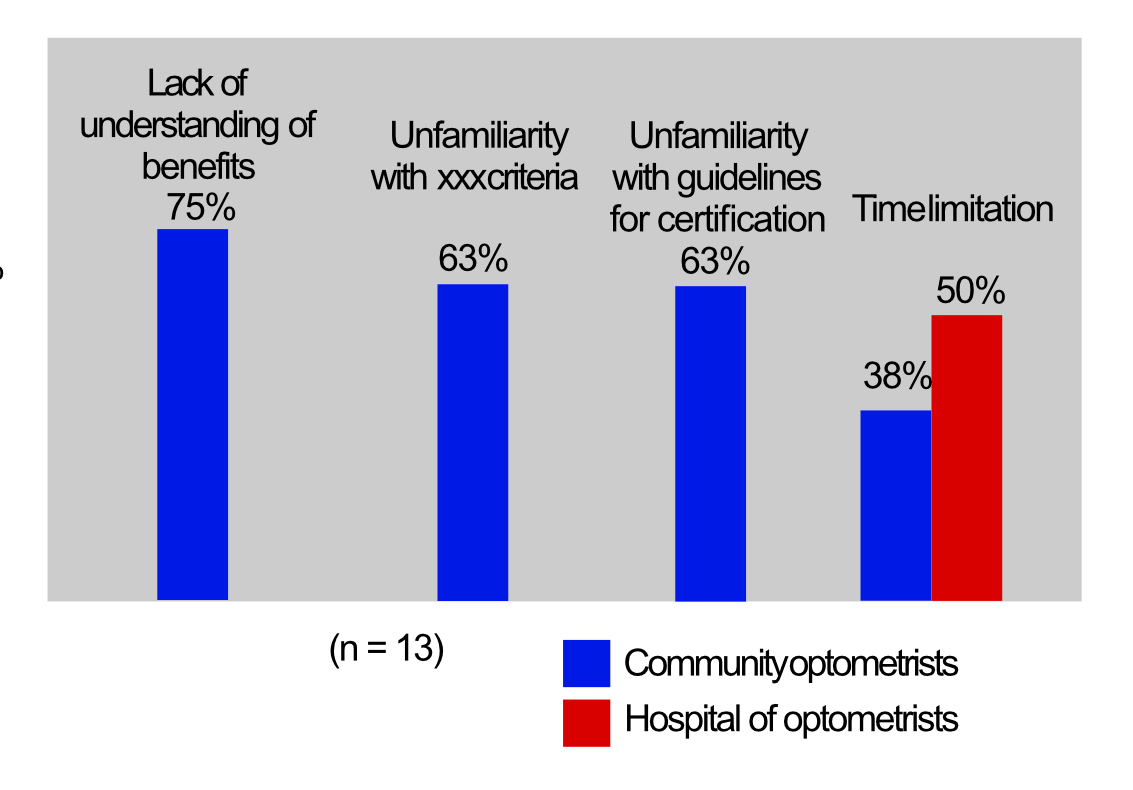

Perceived barriers for discussing or referring for SI/SSI certification

For community optometrists, the most important barriers for discussing SI/SSI certification or referring patients for SI/SSI certification were a lack of understanding the benefits of registration (75%) and unfamiliarity with the guidelines for certification (63%) and eligibility criteria (63%). For hospital optometrists, these factors were less important. Time limits however, were the most important barrier for hospital optometrists (50%). This was a less important but still significant factor for community optometrists (38%). One community optometrist felt that it was not their responsibility to discuss certification and assumed that this was the responsibility of the hospital eye service (see figure 3).

Figure 3: What barriers are there for discussing or referring for SI/SSI certification?

Benefits of registration

All community optometrists completing the survey indicated they had minimal or no knowledge about the benefits of registration. The specialist low vision hospital optometrists (n=2) stated that they had good knowledge of the benefits. The other hospital optometrists felt they had fair (n=3) or minimal (n=1) knowledge. Three (community) optometrists stated they did not discuss benefits with their patients when considering a referral for certification. Three (hospital) optometrists indicated they relied on the Patient Support Service (PSS) or Eye Clinic Liaison Officer (ECLO) to discuss registration benefits in more depth. The role of the PSS or ECLO service is to liaise between clinical eye care professionals and rehabilitation and social care.

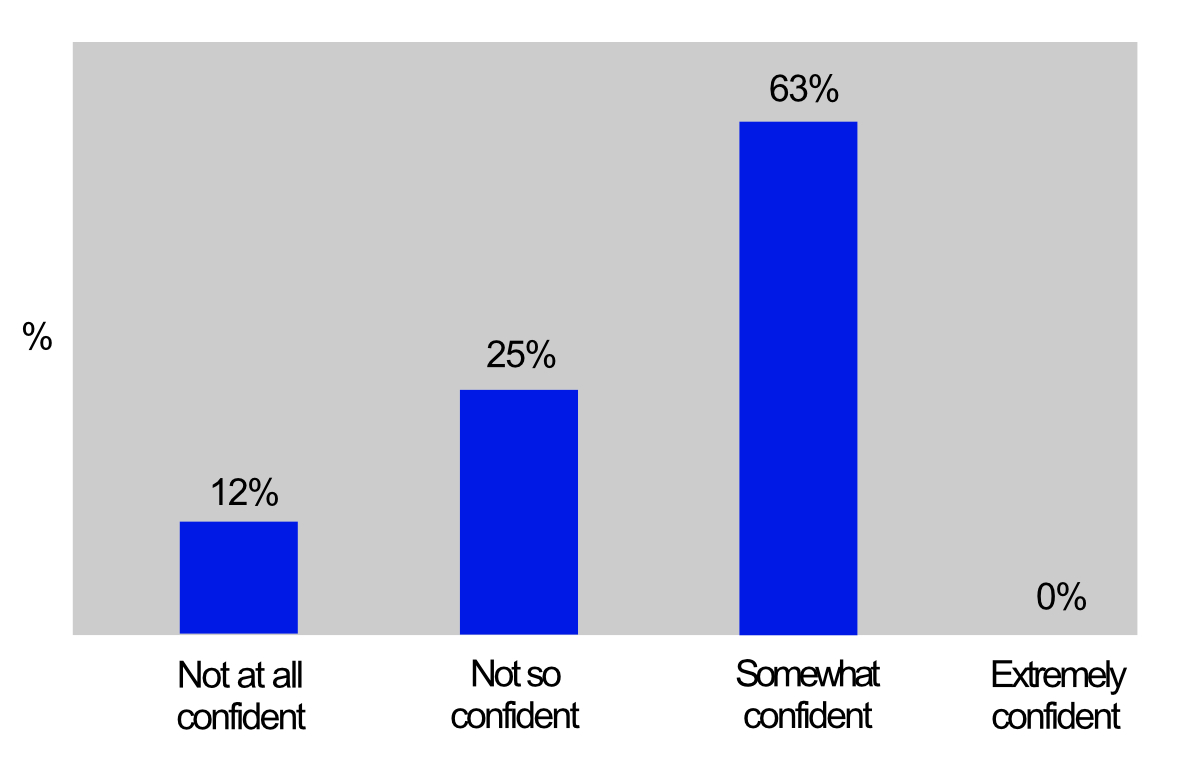

Confidence about certification guidelines

Two thirds of hospital optometrists felt very or extremely confident that they understood the guidelines for certification. Community optometrists felt somewhat confident (63%), not so confident (25%) or not at all confident (12%), as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Confidence about understanding of certification guidelines among surveyed community optometrists

Timing of certification

Optometrists were then asked when they felt it would be a good time to discuss certification for sight impairment. Ninety-three percent (n=14) would consider certification when the patient is eligible, while 36% (n=5) would consider this when the patient asks for it. Two respondents indicated they tend to think about treating refractive error and the eye condition rather than impact on functioning.

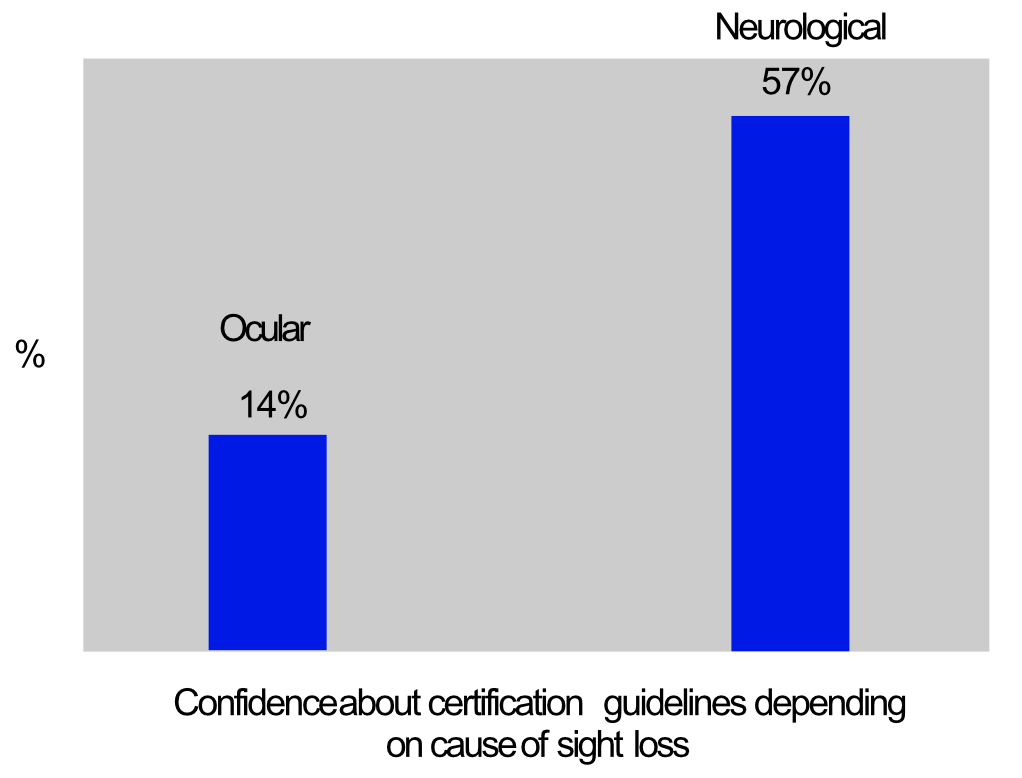

Ocular versus neurological

In terms of confidence regarding certification guidelines, optometrists felt more confident when assessing patients with ocular vision impairment compared to neurological vision impairment. More than half of the respondents (57%) were confident when dealing with ocular vision impairment versus 14% when dealing with neurological vision impairment (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Percentage of optometrists indicating they felt very or extremely

confident about assessing patients for ocular versus neurological vision impairment registration

Visual function

Optometrists were asked when they would consider a referral for vision impairment certification in terms of visual acuity cut-off. There was a wide range of responses, from 0.30 logMAR (6/12) to 1.00 logMAR (6/60). The average cut-off value was 0.4 LogMAR (6/15).

Three respondents indicated they would consider a referral for certification with any visual acuity value, while a number of respondents mentioned that it depends on the visual field as well.

When assessing patients for potential certification, visual acuity was judged to be an important or extremely important factor by 71% of respondents. Twenty-one percent of respondents valued contrast sensitivity as a relevant measurement and no one indicated this was a regular part of their assessment. It appears that contrast sensitivity tests are not widely used in community practices, despite their increasing availability in many electronic display chart systems.

All respondents agreed that visual fields were an important visual function and 71% indicated that they usually or always assess this function. The vast majority of respondents considered central scotoma, tunnel vision, hemianopia and lower field impairments to be important factors for vision impairment certification. Patchy field loss, quadrantanopia and simultanagnosia (the inability of an individual to perceive more than a single object at a time) were considered less important.

These findings mirror earlier findings from a survey among ophthalmologists that was carried out by the author a few months earlier, although the ophthalmologists placed less importance on visual acuity.

Quality of life and co-morbidities

The majority of optometrists (93%) indicated that they usually assess quality of life and 21% indicated they usually or always consider other health issues when considering certification.

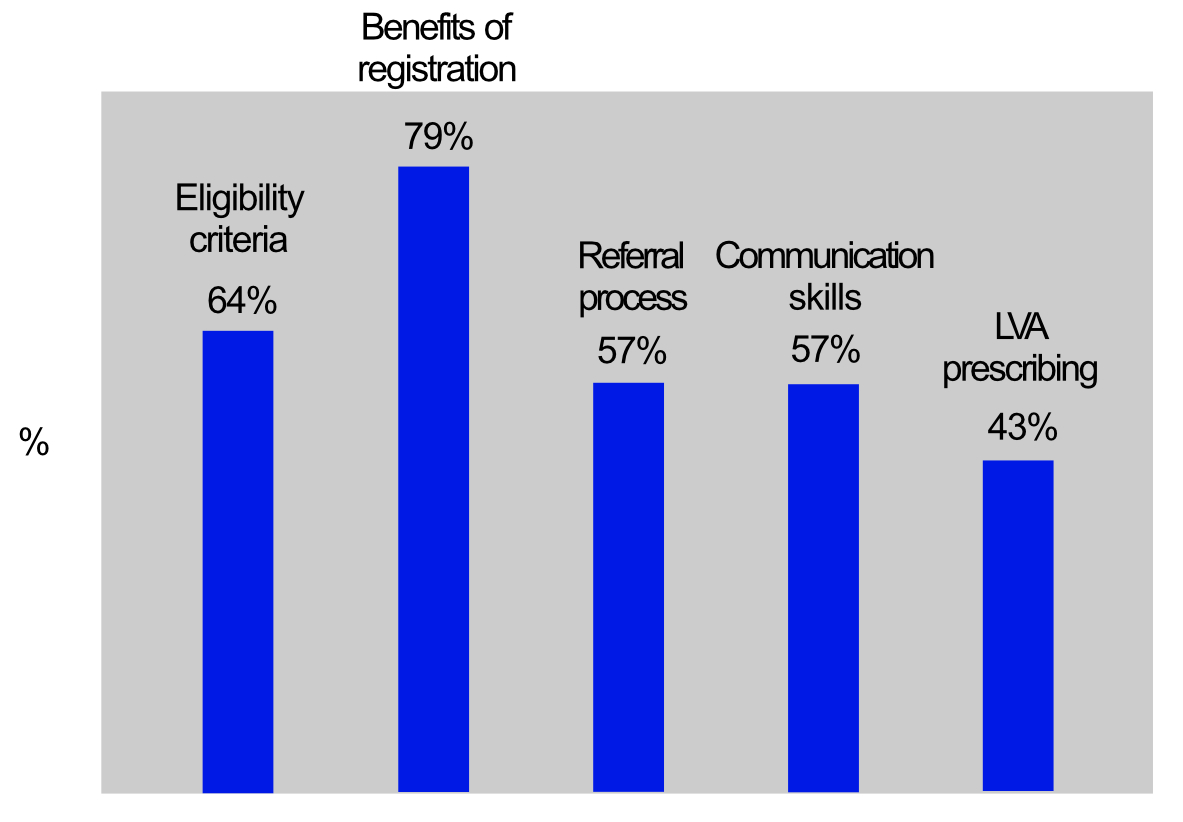

Further training and education

When optometrists were asked if they would appreciate training (figure 6), there was a keen interest in learning more about eligibility criteria for vision impairment (64% of respondents), understanding the benefits of registration (79%), referral into low vision services (57%), communication skills (57%) and prescribing low vision aids (43%).

Figure 6: Percentage of optometrists wanting further training in specific subject areas

Discussion

Although this was only a small sample, the survey has highlighted some of the main barriers for discussing registration and referring patients for certification. Lack of familiarity with benefits, guidelines and procedures were the main barriers in community optometry and time constraints were the main issue in the hospital eye service. Both of these barriers can be addressed.

This article has provided a brief overview of registration benefits and guidelines. However, it can be a challenge for optometrists to retain this information, especially if one does not deal with this patient group on a regular basis. Hospital optometrists frequently liaise with the PSS or ECLO service. The ECLOs are trained to engage with patients about issues arising from sight impairment and they are knowledgeable about the benefits and procedures for sight impairment registration. ECLOs have different priorities to those of eye clinic staff and can afford to spend more time with patients to discuss their needs and questions. With the support from ECLOs, one can address the issues of time constraints and uncertainty about procedures and benefits. ECLOs liaise with the hospital eye staff and can refer patients into the low vision service or liaise with doctors in case certification is warranted.

As hospital optometrists, especially those working in the low vision service, are more likely to encounter patients who meet the criteria for certification, it is not surprising that this group feels more confident about guidelines and procedures. Bartlett et al explored the possibility of giving specialist low vision optometrists authority to sign CVI forms.9 While this may be reasonable for optometrists with specialist low vision training, the current survey suggests that one has to be careful about deciding which optometrists are suitably skilled for this. This is an interesting discussion topic as it could potentially alleviate pressure in busy ophthalmologist clinics.

The explanatory notes for certification of sight impairment provide information about visual fields and visual acuity. It appears that optometrists pay less attention to patchy field loss, quadrantanopia and simultanagnosia, despite the fact that these field impairments do affect every day functioning. Cloudy, blurry, superior and patchy fields are included in the explanatory notes. Simultanagnosia is not specifically mentioned in the explanatory notes. However, patients with simultanagnostic vision may experience severe reduction of visual field, something akin to the tunnel vision found in advanced glaucoma or retinal dystrophies.

Ultimately, one has to remember that the impact of vision on functioning and QoL are the most important factors for deciding if sight impairment registration is indicated. Contrast sensitivity is an important predictor for QoL and should therefore not be overlooked.7,10 One could argue that ‘cloudy fields’ are a description of reduced contrast sensitivity, but it may be more appropriate to include specific criteria about contrast sensitivity in the explanatory notes.

The explanatory notes do not include any guidance on neurological vision impairment other than including cortical or neurological visual impairment in the list of causes. This tends to be more challenging to assess, as it may involve higher processing dysfunction. Impaired perception of motion, dorsal stream dysfunction and difficulties in visually cluttered environments and face, object and place recognition impairments are some of the higher processing problems that patients face. They can have a profound effect on functional vision and render patients functionally blind. Both optometrists as well as ophthalmologists indicated that they were less confident in assessing these patients for sight impairment certification and, therefore, more guidance is desirable.

Final Thought

This article has explored understanding of the guidelines and procedures for sight impairment certification and registration and common barriers to this understanding. Although the focus in this article is sight impairment certification and registration, not every patient with sight impairment is eligible for this. For any patient who is experiencing difficulties as a result of reduced functional vision, a referral to low vision services is warranted. Early intervention from low vision services is recommended to minimise any impact on QoL.1 Optometrists, and other eye care professionals, are well placed to introduce patients with visual impairment to appropriate services for optimal support and management.

- Cirta Tooth is a specialist low vision optometrist, working in both private practice and the hospital eye service.

References

- NHS. 2007. Recommended Standards for Low Vision Services: Outcomes from the Low Vision Working Group, commissioned by the Eye Care Services Steering Group. Available at: http://www.eyecare.nhs.uk/evaluationdoc.aspx [Accessed on 14 February 2022]

- Department of health. 2017. Certificate of vision impairment: Explanatory notes for consultant ophthalmologists and hospital eye clinic staff in England. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/637590/CVI_guidance.pdf [Accessed on 14 February 2022]

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-published-on-registering-a-vision-impairment-as-a-disability

- https://beta.isdscotland.org/topics/eye-care/certificate-of-vision-impairment-cvi (Note: website accessed March 2022 is still beta-testing)

- Alahmadi BO, Omari AA, Abalem MF et al. 2018. Contrast sensitivity deficits in patients with mutation-proven inherited retinal degenerations. BMC Ophthalmology 18. Article Number 313

- Bennett CR, Bex PJ, Bauer CM et al. 2019. The assessment of visual function and functional vision. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology 31(SI), pp.30-40

- Johansson L, Skiljic D, Falk Erhag H et al. (2020). Vision-related quality of life and visual function in a 70-year-old Swedish population. Acta Ophthalmologica 98(5), pp.521-529

- Roh M, Selivanova A, Shin HJ et al. (2018). Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity are two important factors affecting vision-related quality of life in advanced age-related macular degeneration. Plos One 13(5). Article Number e196-481

- Bartlett R, Jones H, Williams G et al. 2021. Agreement between ophthalmologists and optometrists in the certification of vision impairment. Eye 35(2), pp.433-440

- Brussee T, van den Berg TJTP, van Nispen RMA et al. (2018). Association between contrast sensitivity and reading with macular pathology. Optometry and Vision Science 95(3), pp.183-192