The subject of myopia and its progression has taken a prominent place in the optical industry over recent years, and the advent of Covid-19, with its associated lengthy lockdowns, has exacerbated the problem. Many children who, in more normal school times, were out in the playground three times a day have been at home, sitting in front of a laptop for extended periods of home education, and recent research publications from Canada and Asia have noted an increase in the rate of myopia progression among these younger patients.1,2

For many eye care professionals (ECPs), the wealth of research into myopia management and the range of management options entering the market in a relatively short space of time may seem intimidating, and some may have wondered whether tackling this is the province of all ECPs, or just the experts in the field.

The World Council of Optometry, of which the College of Optometrists is a member, is an international membership organisation for the development of optometry and has defined a clear evidence-based standard of care for myopia management and advises all optometrists to incorporate it into their practices. This standard of care comprises three elements – mitigation, measurement and management,3 meaning that parents and children should be educated about myopia and its consequences, children should be evaluated for risk of developing myopia, and evidence-based interventions to slow the progression of myopia should be offered where appropriate.

How do we know who is at risk?

There are a number of factors that we can take into account when assessing the likelihood of a child developing myopia. The Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Ethnicity and Refractive Error (CLEERE) study shows that it is largely possible to predict a myopic future by refractive error at certain ages.4 For example, if a child has less than +0.75D of hyperopia at age six years, they are likely to become a myope, as is a nine to 10-year-old who is +0.25DS or less. The 2020 report from the Northern Ireland Childhood Errors of Refraction (NICER) research study also show that children at the age of six to seven years with a spherical error of refraction (SER) of +0.19DS or less, at least one myopic parent, and an axial length of 23.19mm or more, were at greatest risk of becoming myopic by the age of 10 years.5

Parental myopia is a good indicator of the likelihood of a child becoming myopic, and it has been shown that there is a threefold increase in the likelihood of myopia for a child with one myopic parent.6 If both parents are myopic, then the child is seven times more likely to develop myopia than a child of non-myopic parents.6 If we combine refractive error and parental myopia, then we see that a six-year-old child who has +0.75D of hyperopia or less and two myopic parents has a 75% chance of becoming myopic by the age of 13 years.7

The NICER study suggests that children age six to seven years should have an annual eye examination if they have a positive family history of myopia, are emmetropic or low hyperopes or have a sedentary lifestyle of less than three hours outdoors per day.6 A recent meta-analysis of 15 articles showed smart device exposure might be associated with an increased risk of myopia, but further research is required.8

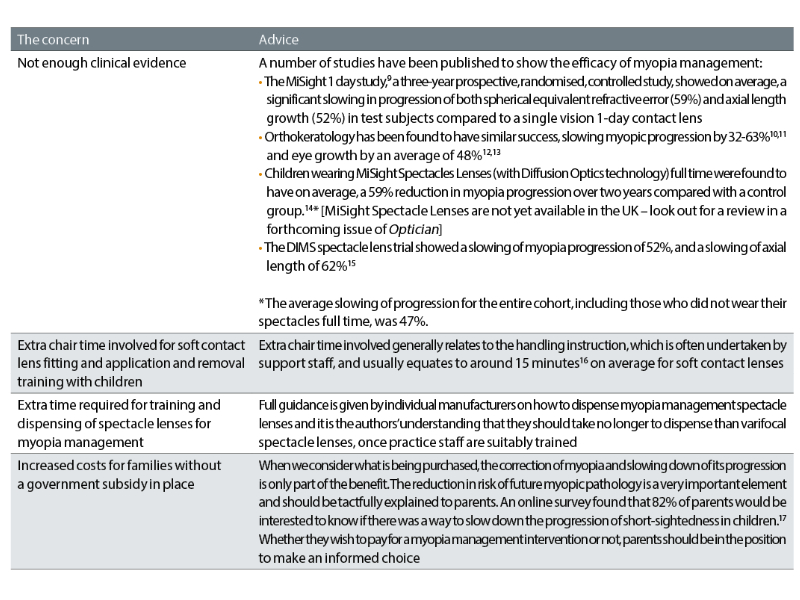

Table 1: ECP Barriers to offering myopia management

What are the barriers to ECPs providing myopia management in practice?

Some ECPs are reluctant to offer myopia management for a variety of misperceptions, some of which are listed in table 1.

What are the benefits of providing myopia management in practice?

Myopia management offers significant benefits for children. Slowing the progression of myopia, and therefore potentially reducing the ultimate prescription, means a child can expect a better visual future. While they are still going to be myopic, unaided vision is likely to be better than it would have otherwise been. Choice of spectacle frames may be wider and there may not be a need for costly high index spectacle lenses. Patients may also have a better outcome if they were to undergo refractive surgery when older.18 Slowing axial length growth is a major benefit of myopia management and is likely to reduce the risk of myopia-related pathology such as retinal detachment, glaucoma and myopic maculopathy later in life.19 In the UK, myopia is currently the third most common cause of binocular visual impairment in the over-75s after age-related macular degeneration and cataracts.20 This can add to chair time during future eye examinations as lengthy explanations are made and patients are referred for treatment. A 50% control effect would lead to a reduction of more than 90% in the frequency of myopia over -5.00DS.19

There is a definite expectation from parents that an ECP should offer advice on myopia and the options for management. A YouGov questionnaire in 2019 found that 69% of parents want to know about eye health risks associated with worsening myopia in children, and 89% would be interested to know if there was a way to slow down progression. Ninety-two percent of those questioned said they would expect their ECP to tell them about all available eye care options that could help slow progression of myopia.17

The practice can also benefit from providing myopia management to children. It has been shown that contact lens wearers demonstrate greater practice loyalty, especially daily disposable lens wearers when subscribing to a monthly payment plan,21 which may help to build a practice’s patient database and reduce those patients lost to internet purchasing. In addition, myopia management requires full-time wear, whether using spectacles or contact lenses, which may generate more regular income for the practice. This may be considered an immediate benefit to the practice, with the significant, potential longer term patient benefit of slowing down myopia progression and reducing the risk of myopia-related pathological problems in the future.22

Where to start in myopia management

For many ECPs, myopia management is a new area of expertise, but there are plenty of ways to learn more and expand skillsets. Most optical conferences provide informative content on research papers, myopia management options and advice on incorporating this valuable element into everyday practice, and there are opportunities for professional education too, for example the BCLA Myopia Management Certificate,23 and Myopia Profile online learning courses.24 Manufacturers who offer myopia management products also provide training and support, and there are professional associations, groups, online websites and social media groups devoted to the subject.

As a starting point, ECPs are well placed to offer advice to mitigate myopia, as advised by the WCO, and at first this may be as simple as discussing lifestyle and behavioural strategies to delay onset with more outdoor time27 and less screen time.8

Parents should be made aware that myopia onset and progression can be managed as well as corrected and be given valid reasons for doing so. Studies have shown a generational difference in that a child is likely to become more myopic than their parents,25 and ECPs are ideally placed to help parents understand this.

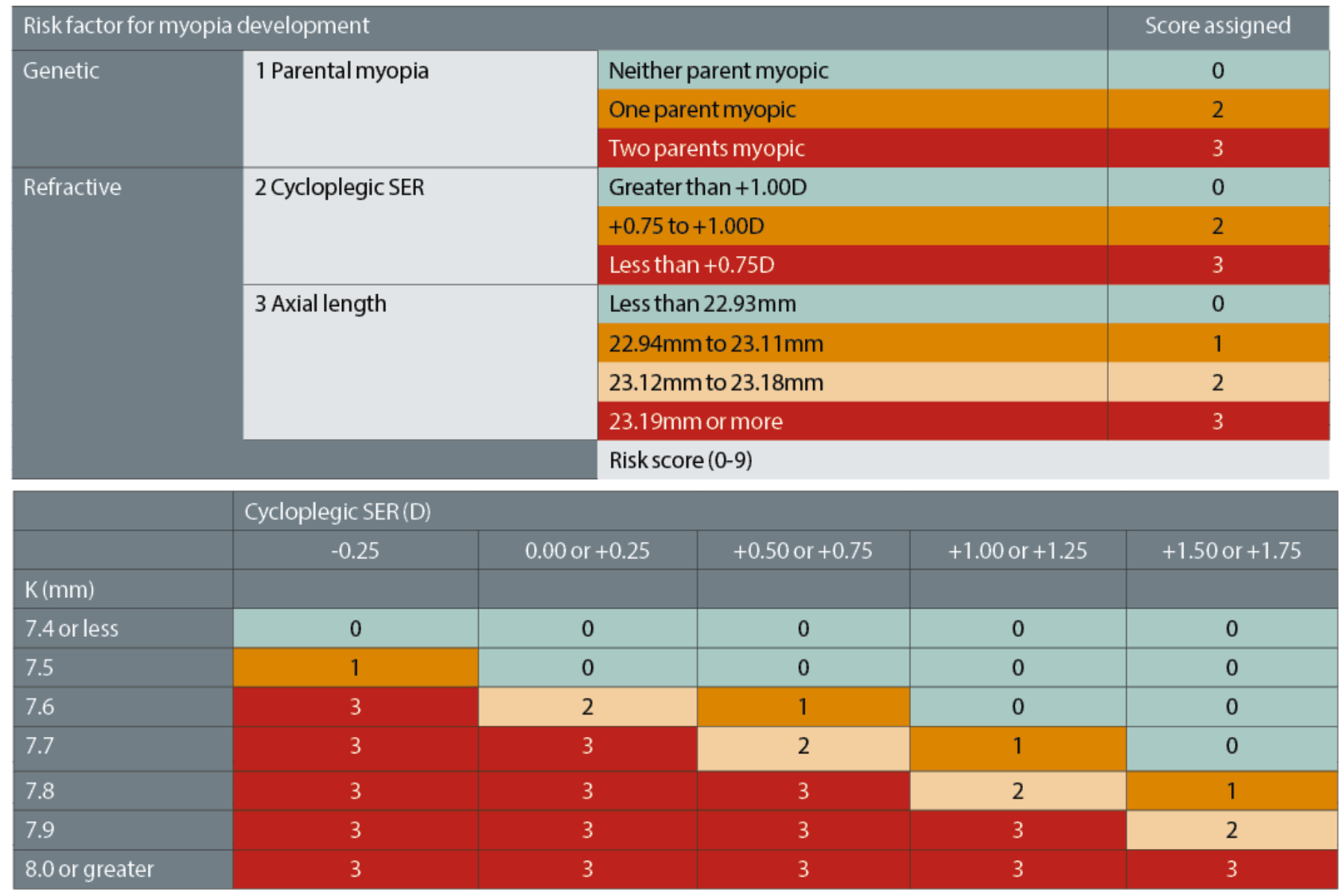

Table 2: Assessing the risk of myopia for children aged six to eight years.26 With kind permission from Ulster University, United Kingdom

Table 3: Estimations for risk score from average keratometry (K readings, mm) & cycloplegic spherical equivalent refraction (D).26 With kind permission from Ulster University, United Kingdom

The Predicting Myopia Onset and Progression (PreMO) risk indicator tables,26 produced from the results of the NICER study,5 may be useful tools for ECPs, to help them assess the likelihood of a child becoming myopic. The NICER research team have created two sets of tables; one for children aged six to eight years and one for children aged nine to 10 years. Table 2 shows the scoring table for the younger age group.

There are further tables (table 3) to assist those who do not have access to cycloplegic refraction data and/or axial length measurement, enabling a score to be assigned for all children.

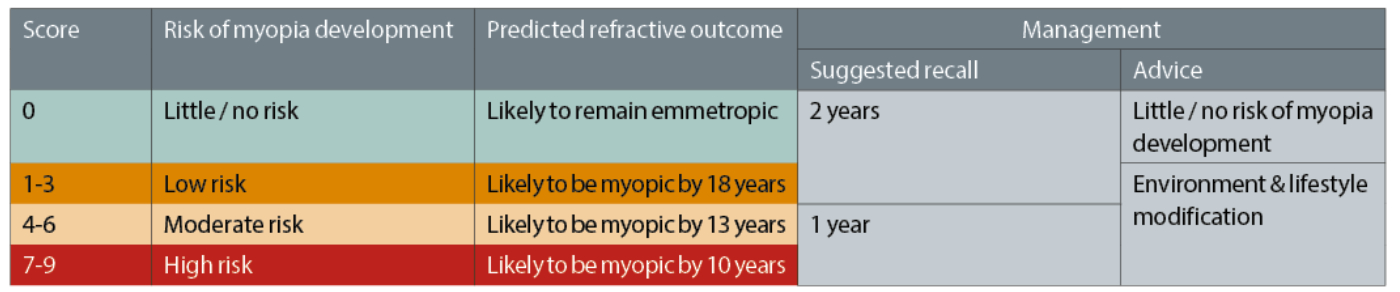

The scores from tables 2 and 3 can then be interpreted into a level of risk using table 4, which also offers a suggested recall timeframe and management options advice.

Table 4: Predicted risk of myopia development and suggested management options and advice.26 With kind permission from Ulster University, United Kingdom

Available options in practice

If a child is not yet myopic but at risk of becoming so in the future, based on parental history, refraction and axial length, then environment and lifestyle advice can be offered – more outdoor time, and less screen time. It has been suggested that a 50% reduction in the risk of developing myopia may be achieved by spending an average of 76 minutes outdoors per day.27

This is also a good time to discuss possible myopia management options with the family, so that they have time to think about the options and ask any questions they may have. When a child develops myopia, the correct moment to begin optical intervention may be difficult to determine, as until the child notices a drop in unaided vision it may be difficult to persuade them to wear either spectacles or contact lenses. When a distance blur becomes noticeable however, this is an ideal time to revisit the earlier conversation about management and formulate a plan with the parents and child. They may not feel ready to embrace contact lens wear yet and may wish to begin with spectacle management for the time being.

It is important to note that compliance with full-time spectacle wear for waking hours, including for close work, is necessary for the purpose of myopia management. Conversely, for a very active child who engages in a lot of sport, contact lenses may be the ideal primary correction from the beginning, and for those children who wish to be correction-free during the day or who swim often, orthokeratology contact lenses may be the best intervention for myopia management.

A child’s myopia management journey

Let us consider a child’s possible myopic progression. Ben presents for his first eye examination at age six years. His mother is a -4.00DS myope, and his cycloplegic refraction is found to be plano in right and left eyes, with axial lengths of 23.11mm and 23.05mm respectively. This gives Ben a PreMO score of six, putting him at moderate risk of becoming myopic by the age of 13 years. The ECP discusses the probability of myopia with Ben’s mother, advising more outdoor time and less screen time, and suggests a one-year follow up.

One year later, Ben’s cycloplegic refraction is -0.50DS in the right and left eyes, with axial lengths of 23.16mm and 23.18mm respectively. His PreMO score has now shifted to seven, meaning he has moved to being at high risk of myopia by the age of 10 years. As this is discussed, it becomes apparent that his mother is keen to take action to slow down the progression of his myopia, but Ben is happy with his unaided vision and not keen on wearing either spectacles or contact lenses. The ECP explains to the mother that compliance with use of myopia management intervention options will be hard to maintain and that concentrating on lifestyle options, such as outdoor time and limiting screen time, is still useful. A recall period of one year is suggested unless Ben starts to struggle to see the television or board at school.

Ben returns one year later and his prescription has changed slightly to R: -0.75DS and L: -0.50DS. He is still happy with his vision, although does admit it is a bit clearer at the bottom of the chart with the correction. Conventional single vision spectacles are prescribed, and he is advised to wear them full time. A six-month recall is advised, or sooner if he notices his vision worsening.

At the age of eight-and-a-half, Ben’s refraction is now -1.00DS in right and left eyes, with axial lengths of 23.67mm and 23.58mm respectively. He reports that he is now wearing his spectacles full time and agrees that the chart is clearer with the updated prescription. His mother is concerned that his vision is worsening, and myopia management strategies are discussed again. Neither Ben nor his mother are ready to consider contact lenses yet, but fortunately there are myopia management spectacle lenses available, so Ben has new spectacles with myopia management lenses made and agrees to wear them every day from waking up in the morning, through to when he goes to bed, except when playing football.

Six months later, Ben is back for his routine appointment. He has to remove his spectacles for sport at school, and while he has begun to enjoy playing football, it annoys him he cannot see clearly while doing so. His enthusiasm for the game has resulted in him joining a local football club and playing most days with his friends in the park. This means his blurred vision when not wearing his spectacles is a daily issue now, and both Ben and his mother feel that this may be the time to try contact lenses. His refraction is unchanged at this appointment, and he is fitted with soft, dual-focus myopia control contact lenses (MiSight 1 day), keeping his myopia management spectacles as back-up. He responds well to tuition and is soon applying and removing his lenses with ease. He is really pleased with being able to see well, especially on the football pitch, and finds the lenses comfortable to wear.

At the age of nine-and-a-half, Ben comes in for his eye examination and contact lens check-up, and his prescription has changed to -1.25DS in right and left eyes, and axial length is measured to be 24.12mm and 24.01mm respectively. His mother is concerned, and asks why the prescription has gone up, as it seemed to have stabilised with the myopia management glasses. The ECP reminds her that myopia management is likely to slow progression down, not stop it altogether and points out that Ben is significantly taller than he was, and some eye growth is still natural, although at a steadier rate than might otherwise have been the case.

Conclusion

Publications and anecdotal reports suggest there are many children like Ben coming into our consulting rooms and the path to managing their myopia is becoming relatively more straightforward. Even if parents are not yet ready to consider an optical intervention for their child, it is important the ECP ensures the appropriate advice is given, so the family can make an informed choice. If the myopia then progresses, they may be more willing to consider appropriate interventions in the future having heard about the options earlier.

There are undoubtedly more complex elements to myopia management that may be considered and incorporated, but as the late Professor Brien Holden said during a BCLA conference in 2015: ‘We don’t know everything about myopia, but we know too much to sit back and do nothing at all.’ This is especially true now, with the range of clinical interventions offering options to all life-stages and lifestyles for young myopes.

Myopia management is now becoming a recognised standard of care in the optical community and there is a wealth of information that can easily be found for those ECPs who have yet to begin to incorporate this into their regular clinics. Aside from clinical articles and published data on studies, training is available from manufacturers of myopia management contact and spectacle lenses, and there are helpful organisations devoted to the subject, along with many social media outlets. A subject as critical as this should be everyday conversation in practice with staff recommending and following-up with patients and parents on offers of appropriate intervention. So, please do not be too short-sighted about managing a child’s myopia.

- Wendy Sethi is a contact lens optician and consultant for CooperVision based in the UK.

- Elizabeth Lumb is an optometrist and director global professional affairs, myopia management at CooperVision & Krupa Patel is an optometrist and senior manager, EMEA professional services, myopia management also at CooperVision.

References

- Wang J, Li Y, Musch DC, et al. Progression of myopia in school-aged children after COVID-19 home confinement. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2021;139(3):293-300.January, 2021.

- Moore SA, Faulkner G, Rhodes RE, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: a national survey. International Journal of Behavioral & Nutritional Physiology Actions. 2020;17(1):85.

- Folkesson P et al. World Council of Optometry Resolution April 2021 https://worldcouncilofoptometry.info/resolution-the-standard-of-care-for-myopia-management-by-optometrists/

- Jones-Jordan L et al. CLEERE Study Group Early Childhood Refractive Error and Parental History of Myopia as Predictors of Myopia. Investigative & Ophthalmological Vision Science. 2010 Jan; 51(1): 115–121]

- McCullough S, Adamson G, Breslin K, et al. Axial growth and refractive change in white European children and young adults: predictive factors for myopia. Science Reports. 2020 Sep 16;10(1):15189

- McCullough S, O’Donoghue L, Saunders K. Six Year Refractive Change among White Children and Young Adults: Evidence for Significant Increase in Myopia among White UK Children 2016 2016 PLOS ONE Volume: 11, Issue: 1, pp 1-19

- McCullough S, Saunders K. Childhood Myopia in the 21st Century. Optometry Today. June 2016, 69-74

- Foreman J et al. Association between digital smart device use and myopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digital Health. 2021;3:e806–18. Date accessed 1st December 2021.

- Chamberlain P, Peixoto-de-Matos S, Logan N et al. A 3-year randomized clinical trial of MiSight lenses for myopia control. Optometry & Vision Science. 2019 Aug;96(8):556-567

- Charm J, Cho P. High myopia-partial reduction ortho-k: a 2-year randomized study. Optometry & Vision Science. 2013;90(6):530-539.

- Santodomingo-Rubido J, Villa-Collar C, Gilmartin B, Gutiérrez-Ortega R. Myopia control with orthokeratology contact lenses in Spain: refractive and biometric changes. Investigative & Ophthalmological Vision Science. 2012;53(8):5060-5065.

- 0Si JK, Tang K, Bi HS, Guo DD, Guo JG, Wang XR. Orthokeratology for myopia control: a meta-analysis. Optometry & Vision Science. 2015;92(3):252-257.

- Sun Y, Xu F, Zhang T, et al. Orthokeratology to control myopia progression: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124535

- SGV data on file 2021. Control of Myopia Using Peripheral Diffusion Lenses: Efficacy and Safety Study, 24-month results (n = 256, 14 North American sites)

- Lam CSY, Tang WC, Tse DY, et al.Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segments (DIMS) spectacle lenses slow myopia progression: a 2-year randomised clinical trial. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 2020;104:363-368

- Walline J et al. Contact Lenses in Paediatrics (CLIP) study: Chair time and ocular health. Optometry & Vision Science, 2007 84, (9) 896-902

- Bull Z, Lumb E, Sulley. A Parent and Practitioner opinions on myopia management part 1. Optician, 02/08/19, Issue 8; 27-31

- Bailey M, et al. The effect of LASIK on best-corrected high and low contrast visual acuity Optometry and Visual Science;81 No.5:362-368

- Flitcroft DI. The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Progress in Retina & Eye Research. 2012;31:622-60.

- Evans J, Fletcher A, and Wormald R. Causes of visual impairment in people aged 75 years and older in Britain: an add-on study to the MRC Trial of Assessment and Management of Older People in the Community. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 2004 Mar; 88(3): 365–370.

- Patel N et al. Customer loyalty among daily disposable contact lens wearers. CLAE, 2015;38:15-20

- Tideman J, Snabel M, Tedja M, et al. Association of axial length with risk of uncorrectable visual impairment for Europeans with myopia. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2016 Dec 1;134(12):1355-1363.

- Myopia Management Course (bcla.org.uk) Date accessed 1st December 2021.

- Myopia Profile: Myopia Control & Management. Date accessed 1st December 2021.

- Liang Y, et al. Generational difference of refractive error in the baseline study of the Bejing myopia progression study. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 2013;97:765-769

- PreMO-risk-indicator-for-website.pdf (ulster.ac.uk). Date accessed 1st December 2021.

- Xiong, S et al. Time spent in outdoor activities in relation to myopia prevention and control: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2017: 95: 551–566