Specialist optometrists involved in treating patients are open to the risk of litigation if the patient expectations of the interventions used are not met, or if they feel they have suffered harm as a result of treatment; even if these consequences were completely unforeseen. The claim can either be related to actions taken by the clinician during treatment or, indeed, to the clinician making the decision not to treat.

Professional Development

Specialist eye care diagnostic and treatment options continue to evolve at a rapid pace. Many of these are far more invasive than clinical techniques used in the past and, although they offer new management options previously not possible, they can also carry a greater risk of serious visual loss.

Take, for example, the use of intravitreal injections (IVI) of anti-VEGF for the management of wet AMD. Twenty years ago, it was not possible to help patients with this condition and, without treatment, many ended up being registered as severely sight impaired. The introduction of IVI treatment now means that many patients no longer suffer further vision loss after the first detection of wet AMD and, for some, vision is improved.

There is about a one in 5,000 risk of serious sight loss due to complication following IVI treatment. This is mainly from endophthalmitis, retinal detachment or a central artery occlusion resulting from a severe IOP spike post-injection. Without treatment, however, most people suffer significant visual loss.

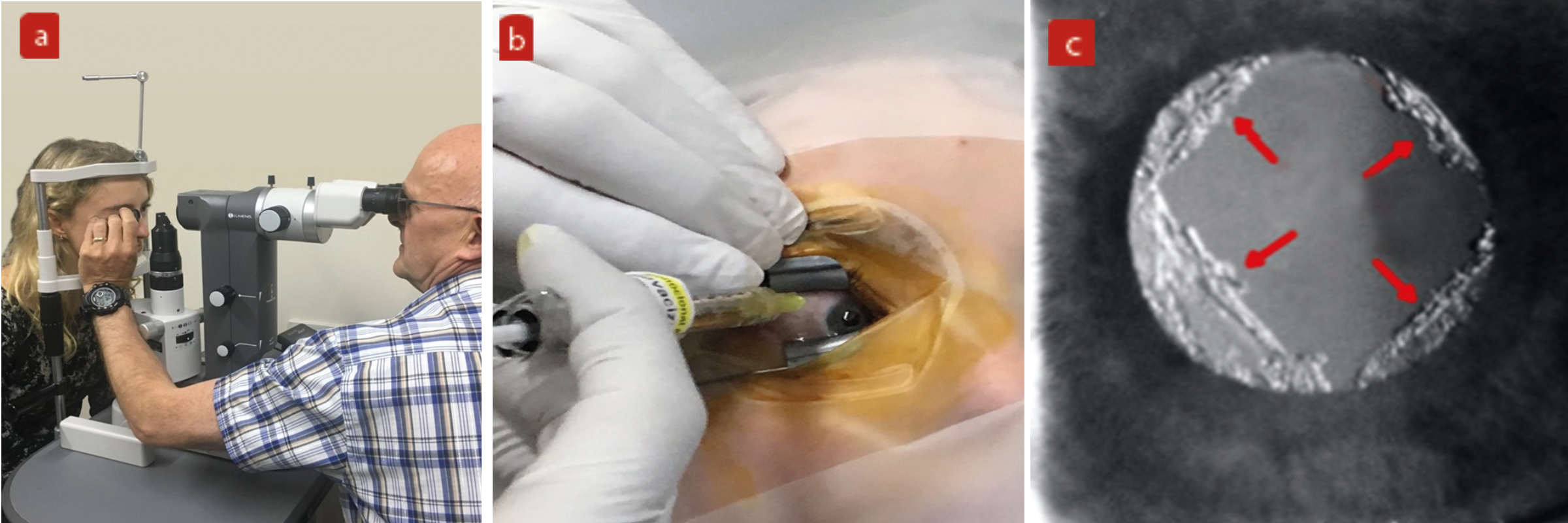

As more and more optometrists start offering IVI and other invasive treatments, such as the use of YAG and SLT laser and IPL therapy (figure 1), it is more important than ever to understand and implement appropriate patient consent protocol. Newer treatments are likely to be yet more invasive, for example the use of radio frequency to remove skin lesions, so now is the time to consider a formal written consent protocol in a practice as opposed to relying solely on verbal consent at the time of the procedure.

Figure 1: Examples of invasive procedures increasingly undertaken by optometrists. (a) Selective laser trabeculoplasty, (b) intravitreal injection, (c) YAG capsulotomy

Verbal or Written

Although a signed consent form is not strictly necessary in law, it can provide useful evidence of consent having been given if questioned later. But it is worth remembering, even if a patient signs a consent form, they may still change their mind and withdraw consent, even mid-procedure.1

Consent may be either explicit, where the patient is asked to consent to a procedure, or implicit, where their actions imply consent to procedures being performed. An example of this might be implied consent to having an anterior eye examination by a patient putting their chin on a slit lamp chinrest.1

Verbal explicit consent would normally be requested before, for example, instilling dilating eye drops or inserting a contact lens during a contact lens trial. It is, however, hard to prove afterwards, and so is usually only used for relatively low risk procedures.

In an exceptional, emergency situation when time is of the essence, for example undertaking an unexpected emergency paracentesis to lower IOP (figure 2), verbal consent may be justifiable so that timely sight-saving treatment can be given. However, the potential need for such an intervention should have been discussed in the information given to the patient prior to consent forms being signed.

Figure 2: Emergency paracentesis to reduce IOP; verbal consent might be justifiable as minimising delay to treatment

Legislation

It is important to recognise that seeking consent for surgical intervention is not merely the signing of a form. It must also include the provision of all the relevant information that enables the patient to make an informed decision to undergo a specific treatment. This is a legal requirement for any medical treatment and is reinforced by professional guidelines.

If a patient is treated without valid consent, it may be considered as assault or battery, under the Offences Against the Persons Act (1861), and can give rise to criminal or civil proceedings.

More recently, section 22 of the Health and Social Care Act (2008), (Regulated Activities) Regulations (2014), makes it an offence for a ‘registered person to fail to comply’ with certain regulations. One such regulation states that ‘care and treatment of service users must only be provided with the consent of the relevant person’. Treatment without consent would be a crime.

To be valid, consent must be given ‘freely and voluntarily’ by a patient ‘with capacity’ who has been given ‘all the information’ he or she needs to reach a decision. Patients should not be subjected to undue pressure or influence by medical staff or their family or friends.

Important milestones in the formulation of current legislation include the following:

The Nuremberg Code

Voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential. This means that the person involved:

- Should have legal capacity to give consent

- Should be so situated as to be able to exercise free power of choice, without the intervention of any element of force, fraud, deceit, duress, overreaching, or other ulterior form of constraint or coercion

- Should have sufficient knowledge and comprehension of the elements of the subject matter involved as to enable him to make an understanding and enlightened decision

Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957]

The ‘Bolam test’ expects the clinician’s standards to be in accordance with a responsible body of medical opinion.

Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015]

A doctor must now tell their patient whatever he/she wishes to know, not merely what the treating doctor thinks they should be told. Rather than attaching their own significance to a risk, they must assess what the reasonable patient would wish to know.

Principles of informed consent

The principles of informed consent for an adult with the capacity to make decisions about their treatment and care must take into account the way information is provided and its nature, the timing of the process and detail of the process itself.

Information

Providing the patient with material information with which to make a decision is a requirement. Facilitating voluntary and informed consent is focused on meaningful dialogue between the parties and this must include:

- Giving information on the diagnosis and nature/purpose of the procedure (including written pamphlets or other media)

- Finding out what matters to the patient and tailoring the discussion to them

- Emphasising their role in the decision making

- Giving information on the expected outcome of treatment

- Discussing any discomfort likely to occur during or after the procedure and how to minimise this

- Discussing not only the expected benefits but also common harms and side effects and any risk of serious harm however unlikely it is to occur (Chester v Afshar [2004])

- Discussing the consequences of non-treatment

- Discussing the possibility of alternative treatments or treatment elsewhere with a different clinician/getting a second opinion

- Discussing national guidelines for treatment and explaining reasons for not following current guidelines (if appropriate)

- Discussing the cost and duration of treatment

- Discussing any follow up treatment

- Giving the opportunity to ask and then answering any patient queries

- Informing the patient of which clinician will be involved in treatment

- Explaining that the patient can change their mind at any time

The initial delivery of information can be face-to-face or virtually (via Zoom and similar). The patient record should be annotated to document that this discussion has taken place.

The discussion should use language that the patient understands and ‘reasonable care’ should be taken to ensure that the discussion has been understood.

By law, patients with disabilities (including sensory loss) must be provided with information (including consent forms and information leaflets) in a format of the patient’s choice (for instance large print, audio and braille). An example of this is the information booklets that are supplied by the IVI drug companies, which include an audio-visual CD explaining the condition and its treatment.

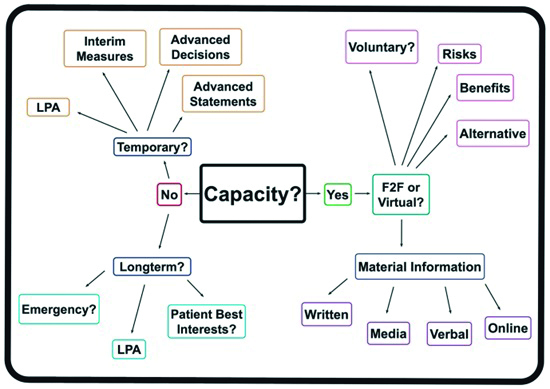

If English is not the patient’s native language, they should be allowed to bring an interpreter to the meeting. It is a good idea to record the presence of this third party on the record. In addition to helping the patient make an informed decision, by understanding the procedure they will be less nervous and more likely to remain calm when treatment takes place. Figure 3 shows a flow chart summary of actions to obtain consent based upon patient capacity.

Figure 3: Gaining informed consent dependent on patient capacity (LPA = lasting power of attorney)

Timing

The patient should be given adequate time to understand the information with which to make an informed decision.

Ideally the consenting discussion would be done some time before the procedure takes place or forms signed, so that the patient has had time to come to a balanced decision and think of any questions and considerations they want to discuss. They should be given a copy of the consent form to read through. This time interval may be shortened somewhat if the success of the treatment would be adversely affected with too long a delay.

Conversely, if treatment is not time sensitive and there has been a long delay between signing the consent form and the procedure, the clinician should confirm the patient’s complete understanding and annotate the form to say that this has been done. It is not necessary for the patient to resign the form.2

For cosmetic and aesthetic procedures, which are not strictly clinically necessary yet could run the potential risk of disfigurement, it is recommended that a delay of at least two weeks be allowed to ensure that even after deliberation, they still wish to proceed with the treatment.

Consenting

The stages leading up to the signing of the consent form are:

- The patient is given the consent and information documents and all supporting media at the time of the discussion

- The patient then is allowed time to review all the information at home ahead of the procedure.

- Further queries arising between the discussion and the procedure can be answered by the clinician if necessary

- The consent form is signed voluntarily

- Both the patient and the clinician have a copy of the consent form

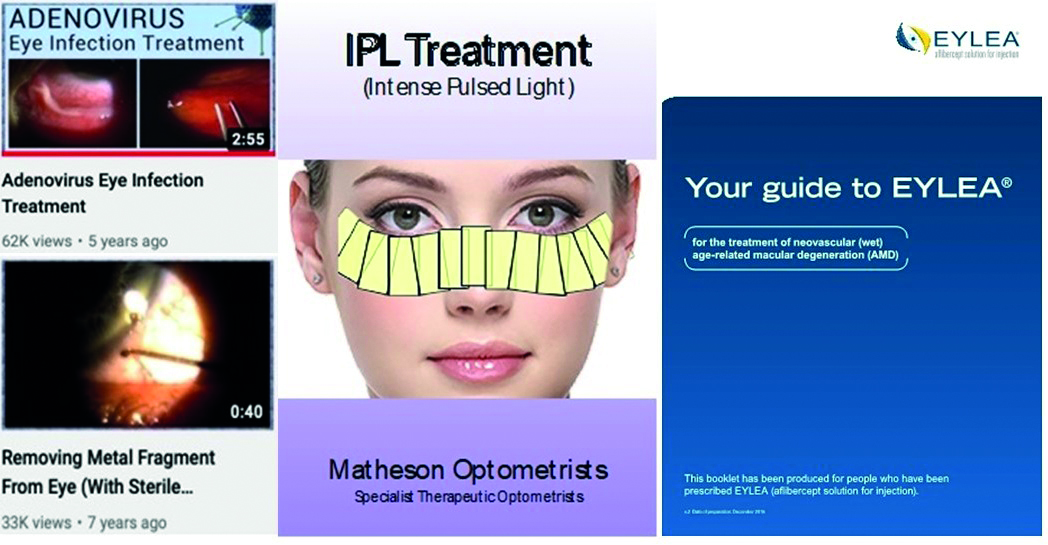

Health professionals must be satisfied that treatment decisions are taken without coercion. Exactly what the patient should do if they have any problems or worries needs to be clearly explained and a detailed list of contact phone numbers and emails, including out of hours if appropriate, needs to be given. This often includes a list of all the local Hospital Eye Department contact details. This information can be included with the consent form. Figure 4 shows examples of information and literature that might be used to support a consent process. Any final queries or concerns can be raised before signing the consent and undergoing the procedure.

Figure 4: Examples of information literature and media

Capacity and Lasting Power of Attorney

A major step in the consent process is to establish that a patient has capacity to give informed consent as per the requirements of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. If a patient is considered as lacking such capacity, for example when unconscious or under ventilation, the clinician must act in the patient’s best interests. Where relevant, seek consent from a person authorised with a lasting power of attorney (LPA) to give consent on behalf of the patient.

There are two types of LPA:

- LPA for health and welfare

- LPA for financial and business interests

These need not be held by the same individual. In healthcare situations, it is only the person with LPA for health and welfare who can give consent for a patient with incapacity. The document showing this authorisation should be reviewed to ensure it is valid. The identity of the third party giving consent and the review of their LPA documentation should be noted in the patient record. This third party should obviously be involved in all the discussions regarding treatment.

The default position should always be to assume that every adult has capacity to consent, though to remember that the capacity will depend upon the complexity of the decision. If an adult does have capacity, no one else should make a decision in their place.

To have capacity, a patient must be able to:

- Understand and remember the information provided

- Weigh up the information provided

- Tell you their decision

If a patient is judged to have capacity to give informed consent, but cannot physically sign a consent form for some reason, verbal consent is acceptable. In such cases, it is good practice to have the verbal consent witnessed by a responsible family member or friend of the patient and for them sign on the consent form that this has taken place.

A patient who either temporarily or permanently lacks capacity can be treated in an emergency situation, for example if to save their life with CPR and defibrillation or to prevent serious harm.

It is important that the action taken is no more than is immediately necessary in the best interests of the patient. Additional treatment above and beyond that necessary to deal with the emergency should not be undertaken.

If a patient without capacity has a known Advance Decision, a stipulation informing any clinician that they do not want a particular treatment performed, then this wish must be respected. This assumes that the patient had capacity at the time of making the Advance Directive. A less clear situation is when a patient has made an Advance Statement of their wishes. This is more flexible, especially if the patient’s situation has materially changed since it was made. Advance Statements should be respected wherever possible.

Children (under 16)

The default position is that an adult with parental responsibility makes the decision for children, but this presumption is overturned if you consider that the child is able to understand the nature, purpose and possible consequences of the proposed examination and treatment, as well as the consequences of

non-treatment.

Gillick competence is a term originating in England and Wales and is used in medical law to decide whether a child (a person under 16 years of age) is able to consent to their own medical treatment, without the need for parental permission or knowledge. Each case should be judged carefully as many in this age group will lack capacity.

The standard is based on the 1985 judicial decision of the House of Lords with respect to a case of the contraception advice given by an NHS doctor in Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority. In this case, the doctor had prescribed contraception requested by a child under 16 as it was felt this was in their best interest and that the child had the mental capacity to understand the situation. However, parental consent had not been sought as it was known that the parent would have refused the prescribing. The House of Lords ruled in favour of the doctor.

Whether parents can override a competent child, and what to do when parents disagree is complex. In the real world, it is unlikely that an optometrist would treat a competent child patient not wanting a procedure performed, even if their parent requested it. A referral to ophthalmology would normally be made.

Young persons (16-17)

The situation when considering treatment of 16 to 17-year-old patients is more complex. If competent and they consent to a procedure, then this is valid. If they refuse, this can be over-ruled in certain circumstances. In practice, an optometrist would be unwise to proceed against the competent 16 to 17-year-old patient’s wishes.

Variable capacity

A patient with Alzheimer’s, vascular dementia and other causes of cognitive impairment may, by the nature of the disease, have varying mental capacity at different times. It is not unreasonable to give them and their carer information about a proposed procedure and reassess capacity on a different day or time when their capacity may be greater. Some would suggest such an action even if their carer or a relative with LPA is present, as it may be less distressing for the patient when they actually come to being treated.

Delegation of consent

Best practice is for the clinician to obtain consent, but it can be delegated. If delegated, the clinician ideally should confirm the patient’s understanding of the procedure being performed before proceeding. If obtaining informed consent is delegated to a colleague, the person obtaining consent should have clear knowledge of the procedure and the potential risks and complications. Ideally, this should be someone who also performs the procedure. They need to be able to answer any questions the patient may have.

Feedback

It is good practice to obtain feedback from the patient after the procedure has occurred. This should focus on the care they received and any appropriate action taken if any harm did actually occur. This documents the level of satisfaction and, if satisfactory, strengthens the case against any future litigation. Apart from any other considerations, this feedback can also improve the care of patients in the future.

Risks with IVI and laser procedures

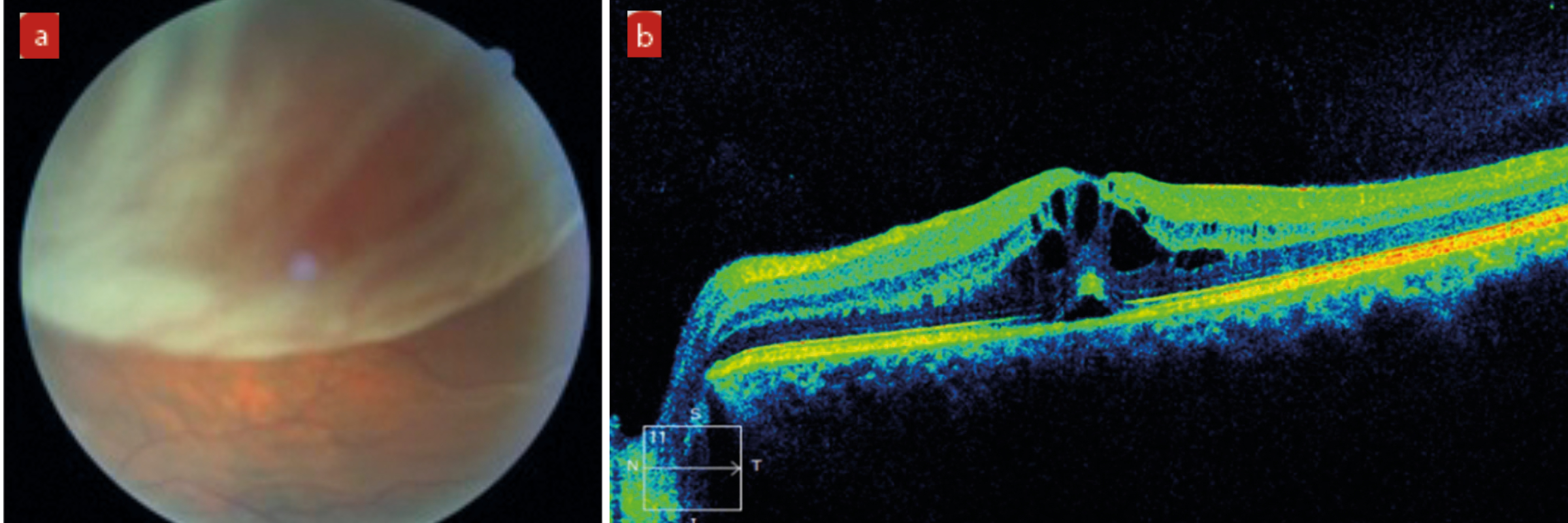

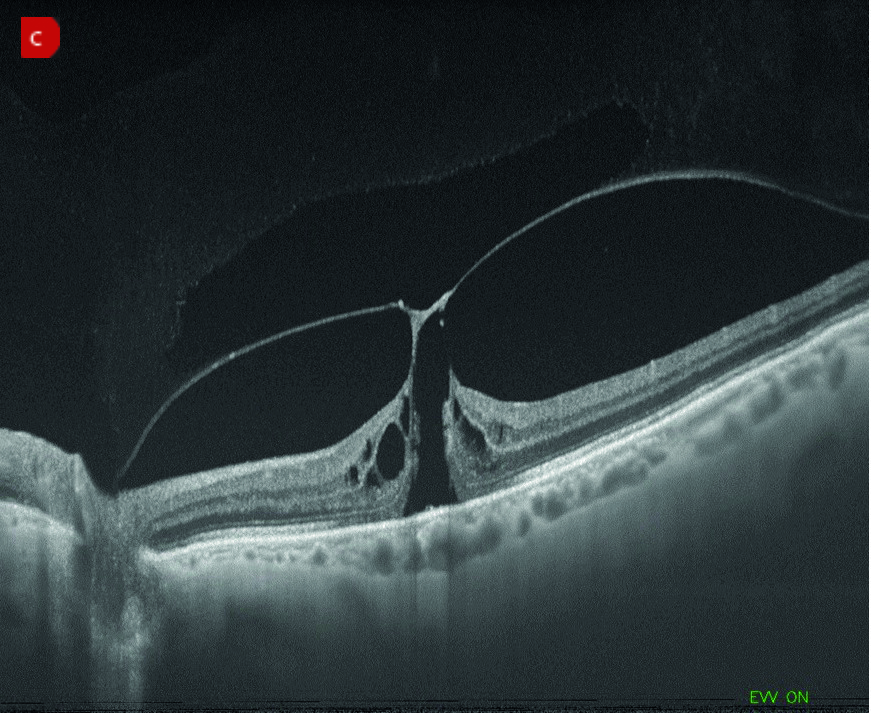

Even though a good outcome is expected, there are certain known risks with IVI and laser treatments which need to be discussed with the patient (figure 5). These include the following:

- Retinal detachment

- IOL damage or dislocation

- Cystoid macular oedema (CMO)

- Increased intraocular pressure

- Anterior uveitis

- Iris haemorrhage

- Corneal oedema

- Macular hole

- Corneal endothelial cell loss

- Endophthalmitis

Any increased risk needs to be identified as soon as possible so any remediation that might be needed can be discussed. In high-risk groups with previous CMO or diabetic retinopathy, NSAID drops are often used to reduce this risk of the procedure aggravating an easily inflamed eye.

Patients with pre-existing vitreomacular traction (VMT) are more prone to progressing to a full thickness macular hole due to shock waves in the vitreous from the treatment laser. An OCT prior to undergoing the procedure can help identify patients at risk and these increased risks emphasised during informed consent. Like with previously high myopes, low power laser settings, probably with a capsulotomy lens being used, produce the lowest risk of this complication.

Iris bleed is rare, but can occur with laser procedures of nervous or non-cooperative patients. Patients in wheelchairs, the severely obese and those with breathing difficulties, all pose challenges as far as keeping their head and eyes still while the laser is precisely focused and fired.

Although these examples of possible complications are somewhat daunting, they are thankfully rare with careful technique and patient selection.

Figure 5: Examples of complications of IVI or laser treatment. (a) Retinal detachment. (b) Cystoid macular oedema. (c) Macular hole with vitreomacular traction

Examples of treatments with more significant risk to the patient

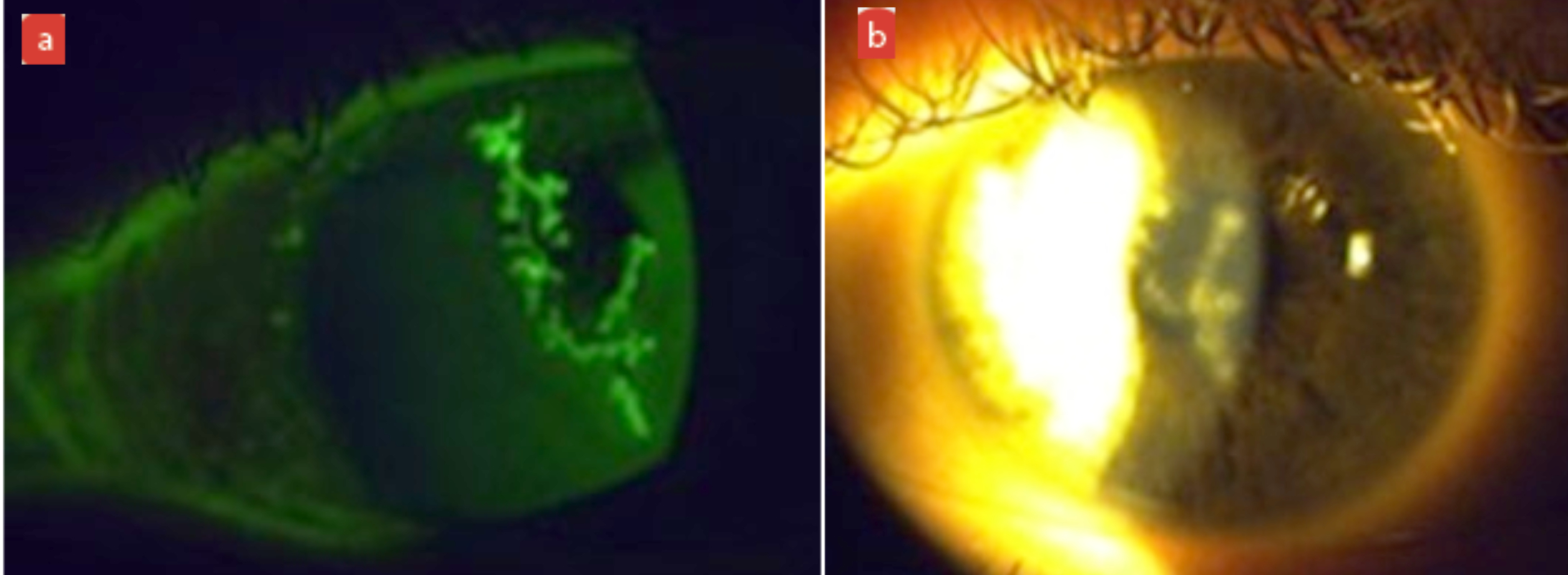

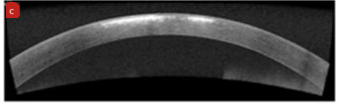

Occasionally, a condition is treated where there is a significant risk that the patient’s vision will not return to normal pre-intervention levels, even with appropriate treatment. A consent form should be signed to make clear that the patient realises that this is the case at the time the intervention is started.

Examples of this may be a centrally located corneal Herpes simplex infection or a centrally located deep metallic foreign body, where permanent residual corneal scarring can remain (figure 6).

A dilemma may arise when no immediate access to secondary HES care is available, as was often the case during lockdown. The only morally acceptable action (in my opinion) is to start treatment, after consenting and seeking advice from consultant colleagues, and to follow up the patient more frequently afterwards. Often in these cases, after the initial emergency procedure is performed, most IP optometrists would then refer for further monitoring and or treatment by ophthalmology for medico-legal reasons.

A sobering thought is that an optometrist, who is adequately trained and accredited to perform a procedure on a patient who has given informed consent and where no actual harm is done, might, because of a risk of harm being present, still be subject to a GOC fitness to practice investigation if it was thought that the College of Optometrists’ code of ethics and guidelines had not been adhered to. It is unfortunate that professional body guidelines often lag behind real world training. In the past, the Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ recommendation that only those ‘medically qualified’ could administer intravitreal injections, persisted for a long time after it became commonplace for it to be performed by other health care professionals.

Figure 6: (a) Centrally located active dendritic ulceration with Herpes simplex infection. (b) Slit lamp image showing residual corneal scarring after treatment. (c) OCT image showing section of residual corneal scarring after treatment

The Importance of Informed Consent for Future Optometrists

The pandemic period has shown the benefits of farming out many diagnostic and treatment tasks to the community specialist therapeutic optometrist. Accreditation in laser and surgical techniques for specialist optometrists has been under way in recent years.

Hopefully, advanced procedures such as YAG capsulotomy, along with SLT laser for open angle glaucoma, laser peripheral iridotomy for angle closure, laser iridoplasty for plateau iris and intravitreal injection treatment for AMD, diabetic macular oedema and vein occlusions, will become services we can soon offer in our practices. Our profession is starting to treat these conditions in hospital eye units and we need to continue to press for them to be available in our community practices. This will enable patients to be treated on their doorstep, by their already respected specialist optometrist, in a timely fashion. Eye units do not have the manpower or clinic time or space to be able to treat everyone. We need to work with our ophthalmologist colleagues to enable this to start happening soon.

As part of this new dawn in clinical specialist optometry, it is important that clinicians adhere to good professional guidance in obtaining valid informed consent before treating patients with these more invasive procedures.

Suitably trained and qualified optometrists are able to provide this treatment conveniently, safely and cost effectively. This will reduce the need for so many hospital review appointments and free our ophthalmology colleagues up for more demanding tasks.

We need to push for this to happen, both in the HES and in private practice.

- Andrew Matheson is a glaucoma specialist therapeutic optometrist involved in emergency community eyecare and glaucoma management and provides hospital laser surgery and intra-vitreal injection services.

- The author would like to thank fellow specialist therapeutic optometrist, Dr Michael Johnson, for his assistance preparing this article.

References

- www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/guidance/communication,-partnership-and-teamwork/consent

- www.rcseng.ac.uk/standards-and-research/gsp/domain-3/3-5-1-consent