Can you visualise the face of a close relative, and the house and street where you grew up? Most people are able to create a mental picture of people and places with their ‘mind’s eye’. However, if you ask someone to rate the clarity of this image on a scale from one to five, whereby one represents ‘no visual image’ and five represents a crystal-clear image, responses vary from person to person. Some people can ‘see’ the face or place with precise clarity and detail. Others struggle to create even a faint image. Some find it easier to visualise places, while others find it easier to visualise faces, objects or landscapes.

We tend to self-reference and therefore to assume that everyone’s visual perception is the same as ours. However, it has long been recognised that this is not the case.1, 2 In recent years, interest in this phenomenon has increased and, in 2015, the term aphantasia was introduced to describe a lack of the ability to create mental visual imagery.3 This is not always a total lack and, because of this, Fox-Muraton has suggested we refer to aphantasia as a spectrum disorder.4

The Greek word Rantasia (spoken as ‘phantasia’) translates into ‘imagination’. In most people with aphantasia, the term relates to visual imagery, though other senses can be involved as well. Researcher Wlodzislaw Duch prefers the term ‘imagery sensory agnosia,’ as he believes this describes the phenomenon more accurately in terms of the neurological phenomenon.5

It is thought that aphantasia is a physiological condition and that this is not usually related to emotional distress.6, 7 Zeman et al. found evidence that the left hemisphere is predominantly involved in creating visual imagery.8 The inferior pre-motor and inferior frontal sulcus, responsible for executive function, and the superior parietal lobe, responsible for visual attention, play a role as well as the superior and cingulate eye fields, responsible for eye movements. The left inferior temporal lobe was found to be activated during visual imagination.

Aphantasia is usually a congenital condition, but some cases of acquired aphantasia have been documented,7 notably as a result of COVID-19.9

Aphantasia can manifest itself as a complete absence of sensory imagery. However, in most cases, the sensory imagery tends to be incomplete rather than completely absent. In the next few sections, the phenomenon of aphantasia will be considered using a case scenario.

Case Report

A young woman with aphantasia since birth had never given much thought to the matter until, in 2020, the topic came up in conversation during which her friend referred to a BBC feature from 2015.10 After this encounter, she decided to contact the researcher, Adam Zeman, who subsequently invited her to take part in a study about aphantasia.

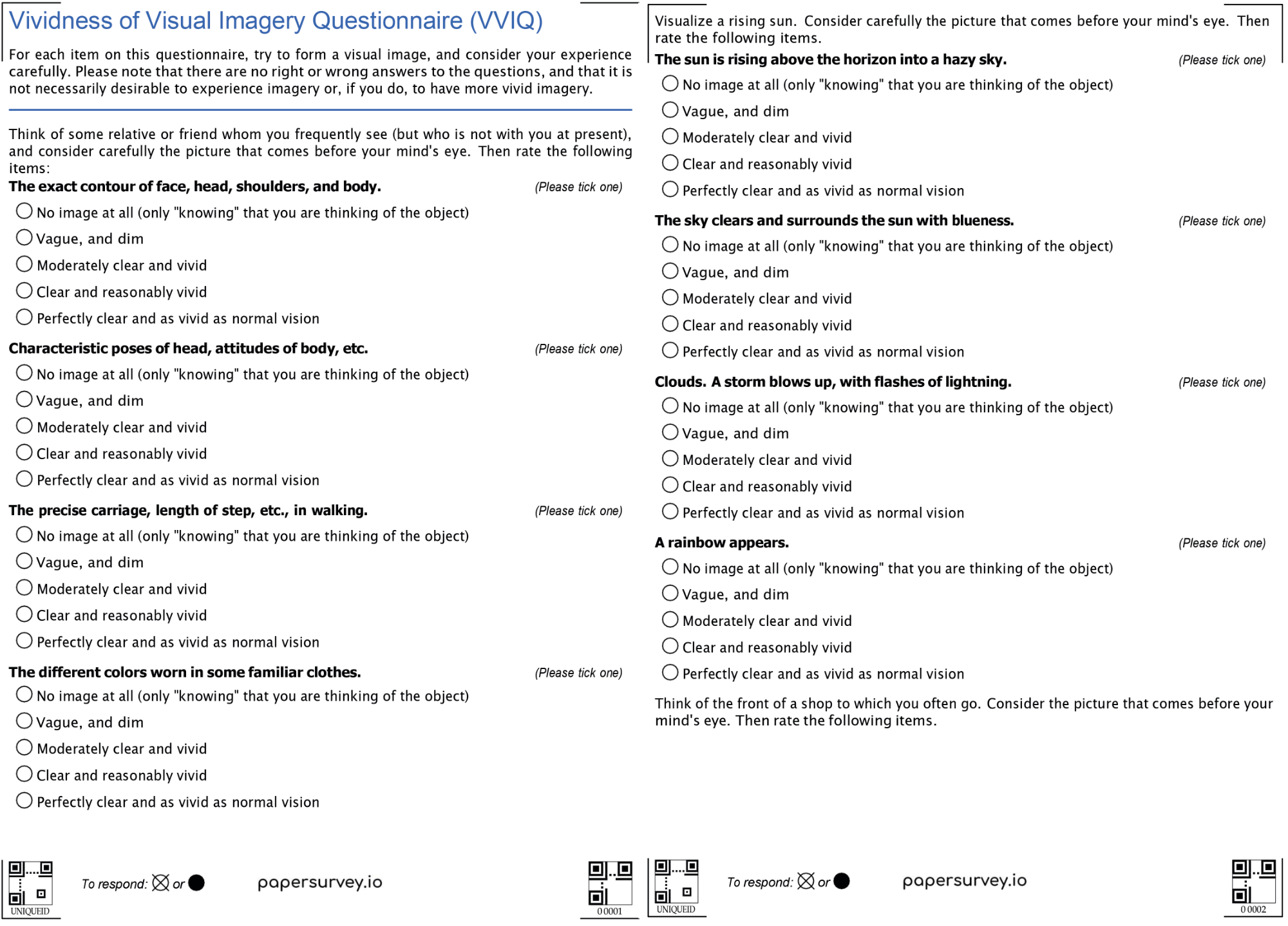

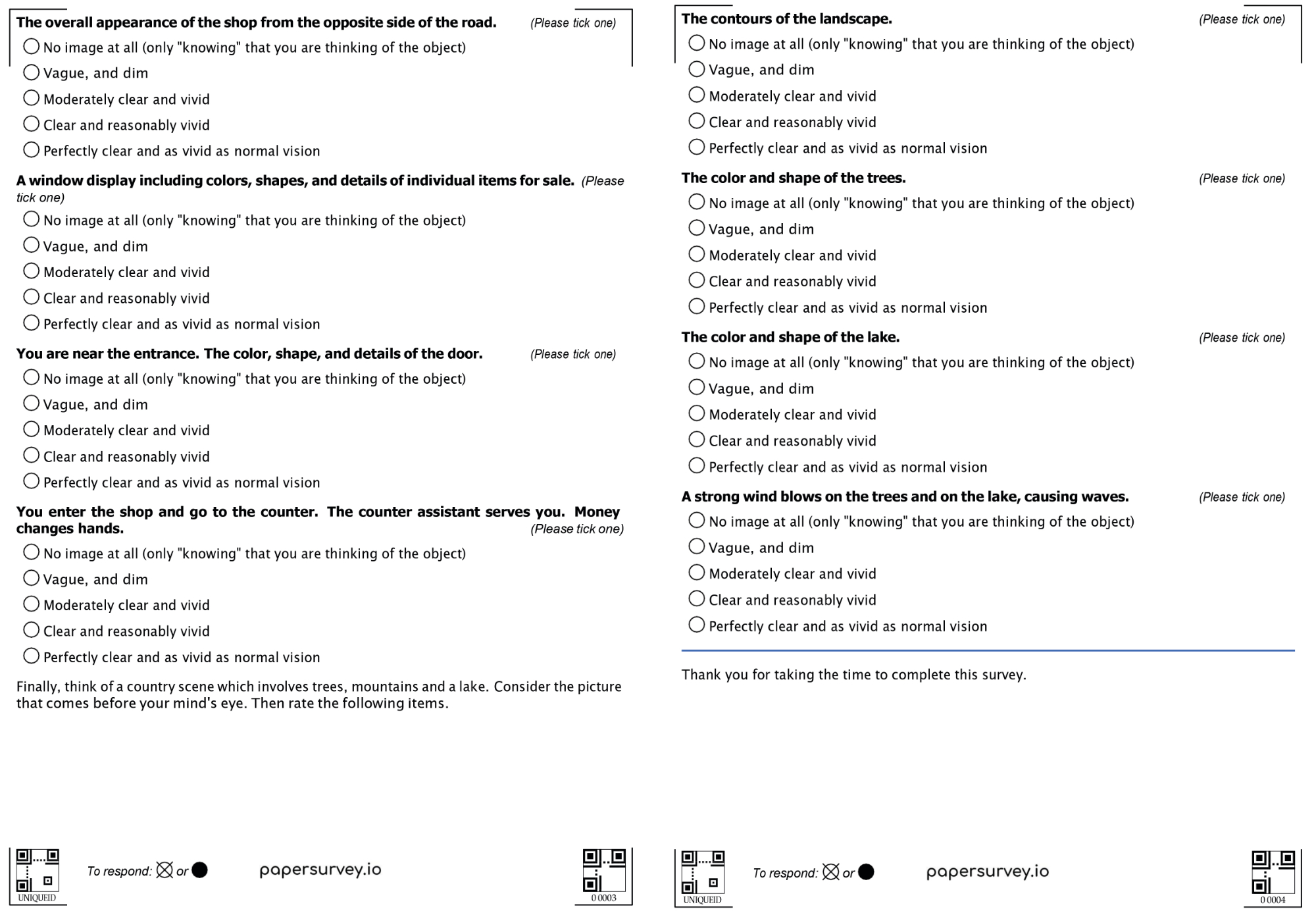

As part of this study, she completed two questionnaires, namely:

- Modified version of the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire

- Imagery Questionnaire

She was also invited for a physical examination, including fMRI. The questionnaires and the physical examination confirmed her diagnosis of aphantasia. Now, a couple of years later, she is keen to improve her understanding about her experience of aphantasia and other visual perceptual dysfunctions and to share her experiences with others.

Symptoms

Faces and places

It transpired that her lack of mental visual imagery is accompanied by a number of other visual perceptual differences. She is unable to create a mental picture of people’s faces and of places and she does not have instant recognition of faces and places when she encounters people and places. Instead, she has to rely on alternative cognitive strategies.

In order for her to recognise her friends and family, she has to rely on her impeccable memory of details and irregularities of people’s faces. She remembers people, for example, by the way their earlobes are positioned, by the way people move their bodies, by their specific gestures and the way they speak.

For navigation, she relies on memory of landmarks (recognised only by recalling specific features) and the number of turnings and road crossings required to get to her destination. She does not recognise buildings in the usual fashion. Instead, she analyses and describes the features in her mind, which she subsequently remembers the next time when she comes across the building. For example, she remembers that there is a school building with little brown bricks, but she is unable to create a ‘picture’ of that building in her mind and could not recognise a building from a photograph.

The inability to visualise familiar scenes was identified when she was first diagnosed with the condition. Her physician asked her to visualise her own house and estimate the number of windows in her house. Unlike most non-aphantasics, who can take a virtual mental visual tour of their house or their neighbourhood, she was unable to do this. Instead, she reasoned that most rooms had two windows and that a house with four rooms must have around eight windows. Although she cannot find her way around using visual memory, she has no problems with spatial awareness. Her ability to judge distances and to reach accurately are unaffected. In fact, she has developed extremely accurate coordination of her upper and lower limbs as a drummer and as a boxer.

Dreams and time travelling

Our patient reported never having been aware of any ‘visual’ dreams and was found, during a three-day sleep assessment, to have a complete lack of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. This is the sleep phase where dreams usually occur. She also reported that she is unable to imagine going back or forward in time, unable to picture what events were like or would be like. She has difficulties processing traumatic situations from the past and wonders if this may be related to her aphantasia. She had never responded well to cognitive behavioural therapy, which invariably involves imagination of past and future events. She also reported that she is unable to attach an emotion to past or future events.

Taste, touch, smell, sight and sound

Aphantasia does not seem to be limited to the sense of vision. Our patient described a lack of formation of mental ‘imagery’ concerning taste and touch as well. She is unable to imagine, or anticipate, the taste of common foods, such as a lemon or banana. She cannot imagine what a hug feels like until she physically hugs someone. However, she describes her auditory imagination to be very vivid and being able to ‘hear’ music and even create music in her mind. She also experienced synaesthesia (a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway) when she was learning to play the piano. In her experience, musical chords have different colours.

Aphantasia and behavioural traits

Our patient has wondered if she might have ‘autistic features’. She describes herself as extremely introverted and she finds it difficult to interpret non-verbal clues in terms of knowing when it is her turn to speak or to remain quiet. Her ability to relate to others seems to be based on her skills in interpreting breathing rates, skin colour and other subtle signs that she can describe and use to create an impression of a person’s emotional state. She describes it as her intuition and an ‘understanding of the rhythms around her’.

Discussion

A hidden condition

It is common for people with congenital aphantasia to only realise in their teens or twenties that their lack of visual imagery is unusual.7 This realisation often occurs in conversation with others who describe the images of their ‘mind’s eye’. It is a relatively common condition with an estimated prevalence of 4%,1 but tends to remain undiagnosed.

Associated prosopagnosia and topographic agnosia

It has been suggested that there may be a relationship between aphantasia and prosopagnosia, as these conditions often co-occur.7, 11, 12 Prosopagnosia is caused by dysfunction of the fusiform gyrus face area, whereby instant recognition of faces is impaired.

In topographic agnosia, instant recognition of places is impaired. The specific combination of prosopagnosia and topographic agnosia has been described in the context of developmental agnosia, whereby different members of the same family described difficulties with face and place recognition.13

In order to function well, people with aphantasia, prosopagnosia and topographic agnosia often need to rely on alternative cognitive strategies as our case report showed. This appears to be a common feature in people with aphantasia.8, 14

Grüter et al found that people with prosopagnosia usually score low on a Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ, figure 2), suggesting a relationship between prosopagnosia and aphantasia.11 They score particularly low on the facial imagination questions, but a number of respondents also score low on questions about non-face objects. The study did not investigate if these people had associated object or topographic agnosia. The VVIQ will be discussed in a later section. According to Dawes et al, impaired spatial imagery is usually not a feature of aphantasia.15 In their study, they asked subjects to copy a picture of a room with several objects from memory. The subjects were able to place the objects accurately but did not draw much detail. The aphantasic participants seemed to accurately remember where things were but not what things looked like.

Figure 2: People with prosopagnosia usually score low on a Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire

Dreaming

The experiences from our case report regarding the lack of dreams echo the findings from Dawes et al,15 who concluded that ‘aphantasic individuals reported fewer and qualitatively impoverished dreams compared to controls’.

Autobiographical memory and mental imagery in human emotion

Our patient showed another feature that is commonly associated with aphantasia; impaired autobiographical memory, or ‘re-experiencing’ events.4, 12, 16 Dawes et al showed that aphantasics have a significant reduction in episodic memories and in the ability to imagine future events.15 Blackwell explains how mental imagery is used in cognitive behavioural therapy to influence emotion, cognition and behaviour and that non-imagery based thought (for example, verbal or semantic) is less effective.17 This may well explain why our patient was unresponsive to cognitive behavioural therapy.

Wicken et al. showed that aphantasics have a ‘dampened emotional response when reading fearful scenarios’ and conclude that this finding supports the theory that visual imagery provides ‘emotional amplification’. However, they also stress that their findings do not indicate that aphantasics are emotionally muted in general. Rather, a significant role of envisioning seems to be one of connecting thoughts to emotions.18

Multisensory aphantasia

Aphantasia usually refers to impaired visual imagery, but it can also involve other senses. Dawes et al reported a total absence of multisensory imagery across all modalities in 26% of aphantasics, suggesting that aphantasia has variable presentations, which can be grouped into subcategories.15

Autism

Dance et al report that people with higher scores on autistic traits are more likely to have aphantasia and that people with aphantasia generally score higher in the autistic subscale of social skills and demonstrate poorer social skills.1 Milton et al echo these findings by concluding that introversion and autistic spectrum traits are more common in aphantasics.12

Interestingly, people who score highly in autistic traits are also more likely to have synaesthesia, a phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. Dance et al have shown that aphantasia and synaesthesia can co-occur.19

The ‘Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire’

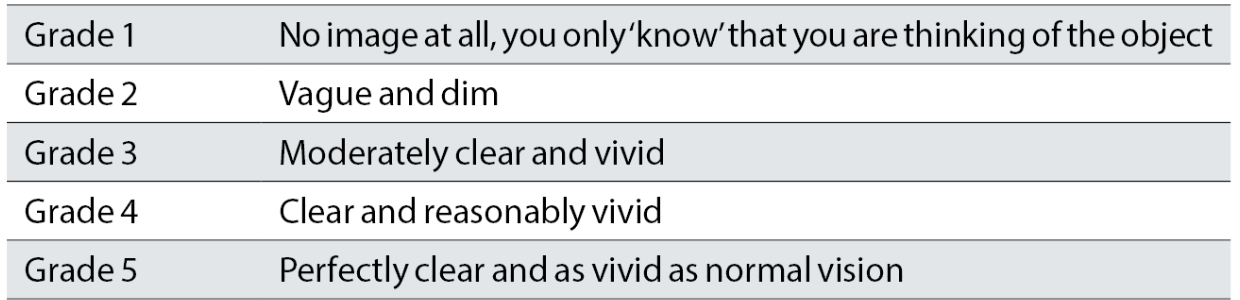

The VVIQ contains a total of sixteen items in four categories. The first category concerns visualisation of a friend or relative, the second category concerns visualisation of a sunrise, the third category concerns visualisation of a storefront and the last category concerns visualisation of a country scene. For each item, one needs to rate the clarity and vividness of the visual imagery (see table 1). For those interested in rating their own score on the VVIQ, the questionnaire can be accessed online.20

The author asked a number of friends and relatives to complete the questionnaire and found a variety of results, ranging from normal, to hyperphantasia or hypophantasia, confirming the notion that visual imagery is markedly variable in nature.

Table 1: Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire grading scale

Auditory imagery agnosia

Auditory imagery agnosia concerns a lack of ability to anticipate or imagine sound.5 One can play a musical instrument accurately by understanding the musical score and then produce the correct notes. However, there is more to music than mechanically producing the correct notes. It involves an interplay of emotion, intonation and sounds, which can only be achieved when the musicians have the ability to anticipate what they will hear and combine this with the feeling that they want to express in their music. People without auditory imagery can learn to play a musical instrument, but may find it difficult to learn tunes by ear or to play along to tunes, at least in Duch’s own experience.5

Let us now consider two scenarios which show the variability of auditory imagination.

Scenario 1

For one person, auditory imagination comes naturally. He can play tunes from memory and learn tunes by ear with ease. He can hear the tunes in his mind’s ear and even compose harmonies and add more voices to existing tunes through pure imagination. Tunes, musical thoughts and complex harmonies often spontaneously form in his mind. He can write these complex musical compositions on paper without the need to play it on an instrument. He can precisely convey the intended intonation and emotion when he performs the music. He can feel the music flow through him, imagining that the music and the accompanying emotions flow in turn through to the audience. For him, looking at a set of musical notes can trigger the sound and emotions from the music.

Scenario 2

A second person may not hear music in his mind’s ear. He can sing songs from memory and he can follow along with others, but he is unable to sing a part in a choir because he is distracted then entrained by the sounds coming from the other singers. He can sing songs from memory, but he does not remember these through imagining what they sound like. He simply starts to sing the tune without knowing how he does it. He dreams in visual imagery and never experiences sound in his dreams. In terms of visual imagery, this same person describes an exceptional ability to create complex multidimensional visual representations in his mind’s eye.

Visual imagery after sight loss

Oliver Sacks, in his book ‘The Mind’s Eye’,21 wonders to what extent we shape our brains through experience. He refers to a book by John Hull, entitled ‘Touching the Rock: An Experience of Blindness’, in which Hull describes his loss of visual images and memories after becoming blind, but he also describes losing the concept of sight. Before losing his eyesight he was able to construct a visual image in his mind, but after becoming blind, he became no longer able to do this yet could construct an image using his other intact sensory modalities. However, not all people who lose their eyesight share this experience. Sacks describes a case of a woman who lost her eyesight in her teens but still considers herself a ‘very visual person’ with vivid visual imagery in her mind’s eye, despite not being able to see with her eyes. Sacks then goes on to describe a number of cases of patients who lost their vision and subsequently developed their visual imagery to become extremely vivid, and other cases of patients who completely lost their ability to visualise scenes or remember faces of close relatives.

Final thoughts

Imagining what something feels like, looks like, tastes like, smells like or sounds like, is a unique experience for each person. Self-referencing leads us to think that we all have the same experiences in our mind’s eye, and our mind’s other senses. However, nothing is further from the truth! Although the concept of aphantasia and the spectrum of (visual) mental imagery has now been recognised, there are still many unanswered questions and it will be interesting to see how further research will unveil some of these current mysteries.

- Cirta Tooth is a hospital optometrist based in Edinburgh with a special interest is low vision and functional vision.

References

- Dance CJ, Ipser A and Simmer J. 2022. The prevalence of aphantasia(imagery weakness) in the general population. Consciousness and Recognition. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2021.103243

- Galton F. Mind a quarterly review of psychology and philosophy. Mind, 1880, (19), 301-318. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/os-V.19.301

- Zeman, A, Dewar M. and Della Sala S. 2015. Lives without imagery: Congenital aphantasia. Cortex, 73, pp.378-380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2015.05.019

- Fox-Muraton M. 2021. A world without imagination? Consequences of aphantasia for an existential account of self. History of European Ideas 47(3), pp.4141-428. https://doi.org/10.1080/01916599.2020.1799553

- Duch W. 2022. Imagery agnosia and its phenomenology. Annals of Psychology [preview: accepted for publication]. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5kjwe

- Keogh R and Pearson J. 2018. The Blind Mind: No Sensory Visual Imagery in Aphantasia. Cortex 105, pp.58

- Zeman A, Dewar M, Della Sala S. 2016. Reflections on Aphantasia. Cortex 74, pp.336-337

- Zeman A, MacKisack M and Onians J. 2018. The Eye’s Mind: Visual Imagination, Neuroscience and the Humanities. Cortex 105, pp.1-3

- Gaber T K and Eltemamy M. 2021. Post-COVID-19 aphantasia. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry 25(3). https://wchh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pnp.714

- Gallagher J. 2015. Aphantasia: A life without mental images. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-34039054 [Accessed on 2nd July 2022]

- Grüter T, Grüter M, Bell et al. 2009. Visual mental imagery in congenital prosopagnosia. Neuroscience Letters 453, pp.135-140

- Milton F, Fulford J, Dance C et al. 2021. Behavioral and neural signatures of visual imagery vividness extremes: Aphantasia versus hyperphantasia. Cerebral Cortex Communications 2, pp.1-15

- Dutton GN. 2003. Cognitive vision, its disorders and differential diagnosis in adults and children: knowing where and what things are. Eye 17, pp.289-304

- Jacobs C, Schwarszkopf DS and Silvanto J. 2018. Visual working memory in aphantasia. Cortex 105, pp.61-73

- Dawes AJ, Keogh R, Andrillon T et al. 2020. A cognitive profile of multi-sensory imagery, memory and dreaming in aphantasia. Scientific Reports Article Number 10022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65705-7

- Zeman A, Milton F, Della Sala S et al. 2020. Phantasia: The psychological significance of lifelong visual imagery vividness extremes. Cortex 130, pp.426-440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2020.04.003

- Blackwell SE. 2021. Mental imagery in the science and practice of cognitive behavioural therapy: past, present and future perspectives. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy 14, pp.160-181

- Wicken M, Keogh A and Pearson J. 2021. The critical role of mental imagery in human emotion: in-sights from fear-based imagery and aphantasia. Proceedings of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences 288

- Dance CJ, Jaquiery M, Eagleman DM et al. 2021. What is the relationship between aphantasia, synaesthesia and autism? Consciousness and Cognition. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2021.103087

- https://aphantasia.com/vviq

- Sacks O. 2010. The Mind’s Eye. London: Picador