In part 1 of this series (Optician 29.07.22), we developed an understanding of autistic visual sensory issues. To summarise, autistic adults can experience various visual sensory symptoms (eg to different aspects of light, colours, patterns and motion). Some of these symptoms are similar to those of visual stress, which is a visual perceptual disorder provoked by high contrast, repetitive patterns. Although non-autistic people would probably experience some of these symptoms, it is the negative impact on daily activities, such as the ability to visit public places or use public transport, that seems to be greater for autistic people. Autistic people try to control the effects of visual sensory experiences, mostly by avoiding symptom-provoking situations, but with limited success.

This article will outline the various challenges to accessing eye care experienced by autistic people.

Autism and vision anomalies

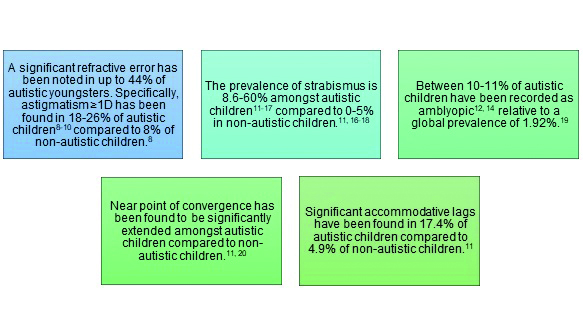

Although visual acuity is comparable between autistic and non-autistic people,1 autistic people are at greater risk of developing optometric anomalies including higher refractive errors, strabismus and amblyopia:2, 3 Figure 1 provides a summary of optometric research in autistic people. These studies were conducted with young autistic participants, having an upper age of 20 years. Additionally, many of them also had a co-existing learning disability. Parmar et al4 attempted to address the lack of research about optometric anomalies in autistic adults without learning disabilities. The outcomes of this study, conducted with 24 autistic adults, suggests this population is more likely to develop a significant change in refractive correction, and present with binocular vision (e.g., accommodative insufficiency and infacility) and visual stress issues. Overlaps have been identified between the symptoms of visual stress and common eye problems such as uncorrected refractive error and binocular vision anomalies;5-7 it is possible that some autistic visual sensory experiences have a similar link.

Figure 1: A summary of reported prevalence of optometric anomalies among autistic people

Overall, if autistic people are more likely to develop optometric issues, they can be expected to need to visit an optometrist regularly. However, are eye care services accessible for autistic people? Are adequate resources available for the provision of autism-friendly services? In general, autistic people face significant barriers when accessing healthcare.21, 22 A survey by the Westminster Commission on Autism23 found 74% of autistic, parent-advocate and professional respondents felt the autistic population receives poorer healthcare than non-autistic people. This could be because some of the physical symptoms of health issues presented by autistic people are erroneously attributed to features of autism instead.24

SeeAbility offer resources for providing accessible eye examinations to autistic children and autistic people with learning disabilities.25 The College of Optometrists have professional guidance on seeing autistic patients, based on research regarding autistic children and mainly focused on what would happen in the testing room.26 Neither of these cater to autistic adults who do not have a learning disability. It would be unreasonable to assume that adaptations made for children or people with learning disabilities will suit an autistic adult. Therefore, it is important to understand the eye examination experiences of this population to make suitable adaptations to services. Parmar et al27 conducted focus groups and interviews with autistic adults for this purpose.

Eye examination experiences of autistic adults

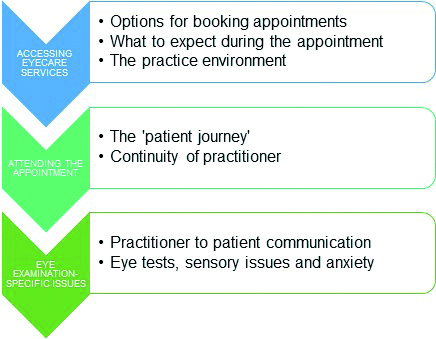

This section summarises the key concerns autistic adults have expressed about eye examinations.27 Autistic adults can face challenges at three key stages of an eye examination: accessing eye care services, attending the appointment and eye examination-specific issues (figure 2).

Figure 2: The three key stages of an eye examination during which autistic adults can face challenges, adapted from Parmar et al27

Accessing eye care services

Options for booking appointments

Due to the social difficulties linked with autism,28 autistic adults commonly feel anxious when communicating with strangers. They do not feel at ease around unknown people and cannot anticipate what they will be like. Of course, this challenge has impacts at various stages of an eye examination.

Booking eye examinations over the phone is very uncomfortable for autistic people. They often have to build up courage to make a phone call to eye care providers (ECPs) in order to access an appointment. Such interactions are kept to a minimum to reduce the stress of having to speak to a stranger. For some autistic people, it serves as a deterrent, making them delay important healthcare until it is unavoidable or someone else can make the phone call for them. Not only does this impact the autistic person themselves, but it also has a knock-on effect on their family members too:

‘My children have had optician reminders for months. One of my children’s been nagging me non-stop to get hers done. … I won’t phone … It would have to be some kind of emergency for me to do that.’27

A relatively recent alternative is to book appointments electronically, for example via an online booking portal or simply by email. Autistic adults strongly prefer these methods, which avoid anxiety-provoking social interactions, maintain a communication trail and allow better control over their appointments. Although research has suggested that electronic booking methods improve appointment attendance for non-autistic people too,29 for autistic people it appears to be more of a necessity to access eye care:

‘If I can book online then I don’t avoid making appointments for four months…’27

This applies to receiving reminders too; emails, text messages or letters are preferred over phone calls.

What to expect during the appointment

Autistic adults feel anxious about visiting optometric practices and having an eye examination. Having an idea of what will be involved in an eye examination can allow them to be less anxious and have greater capacity to deal with any other unpredictable situations. Knowing what to expect involves informing autistic patients about what the practice environment looks like, who they will meet, what tests they will undergo and approximately how long the appointment will last. The simplest approach for this would be a staff member sitting with an autistic patient, upon arrival, and describing what will take place during the appointment. A positive experience shared by a participant in the Parmar et al’s27 study was:

‘…they’d [staff at the optometric practice] tell me exactly, right from the onset, right, that’s the waiting room, you’re going to go through this, then that, then this…that’s generally good anyway…’

A popular method among autistic adults is to be given ‘what to expect’ information in advance of their appointment. This can take the form of an information sheet or webpage, and should include text descriptions, photos and possibly videos too.2, 30 An online resource for ECPs can be accessed at: https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/autism-and-vision/patient_resources.

Additionally, guidance on getting to the practice (e.g., maps, travel routes, public transport options) can reduce travel anxiety. Some autistic people may prefer to visit the optometric practice in advance of their appointment, as an opportunity to familiarise themselves with the setting. Of course, longstanding patients would be familiar with these aspects and may not feel as stressed, but this should not be assumed:

‘Because we already have glasses, they probably assume that we know what’s going to happen.’27

The practice environment

Optometric practices adopt their own interior design and layout styles. However, these features are fundamental to how accessible practices are for autistic adults. Generally, unfamiliar settings have been found to be overwhelming or intimidating for autistic individuals, and this can hinder their attendance.31 Therefore, unexpected changes in practice layout can be disconcerting because of the sudden unfamiliarity.

Unfortunately, autistic adults have noted that optometric practices do not routinely ask patients about special requirements: ‘…there’s never any mention of accessibility…they don’t ask if you have any needs or anything.’27 Obtaining accessibility information is an opportunity for autistic people to state any foreseeable challenges in advance, and for ECPs to appropriately prepare reasonable adjustments. It is a legal requirement as per the Accessible Information Standard.32 This law, in effect since August 2016, ensures people with a disability, impairment or sensory loss receive information that they can easily understand, and any required communication support. Figure 3 summarises the five requirements of the Standard for NHS and social care services and you can visit the following NHS website for further information: england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/ patient-equalities-programme/equality-frameworks-and-information-standards/accessibleinfo.

Figure 3: A summary poster (produced by Healthwatch Suffolk) of the five requirements of the Accessible Information Standard for NHS and social care services33

Experiencing altered sensory reactivity, as discussed in Part 1 of this series, means that autistic adults may have difficulties coping with certain types of lighting, colours of walls and carpets, crowded practices at peak times, lots of sounds (music or chattering) and strong scents (e.g., air fresheners and perfumes). Glare-inducing reflections from spectacles situated near the entrance of optometric practices challenge autistic adults to enter the premises. Quieter and less busy practices are preferred because of fewer sensory stimuli, less stress caused by crowding and a more personal service. It is likely that making adaptations to reduce the sensory difficulties of autistic people in an optometric practice will result in a more comfortable experience.

A study by Cermak et al34 found that adapting the sensory environment of dental practices, such as putting curtains over windows and covering overhead fluorescent lighting, reduced discomfort, pain and anxiety among autistic children. ECPs can refer to a checklist for autism-friendly environments, produced by South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust,35 to assess the accessibility of their practice. This evaluates the possibility of sensory-provoking situations by sensory modality, helping service providers to consider reasonable adjustments and alterations. For vision, some of the questions are:

- Are the colours in the environment low arousal such as cream and pastel shades and not red or vibrant? AND Do any rooms/spaces need a change of paint or wallpaper?

- Have you considered the effect of sunlight from windows or skylights? AND Where the light is at different times of the day? AND Reflective surfaces?

Attending the appointment

The ‘patient journey’

It is commonplace in ophthalmic clinical settings for different staff members to be responsible for stages of the patient’s appointment. Knowing that autistic adults experience anxiety when meeting new people, this type of patient journey is very uncomfortable and has been identified as a barrier to healthcare.22, 36, 37 With time, autistic adults feel less anxious around new people. But, with the typical patient journey, just as an autistic person starts to become comfortable with one staff member, they are handed over to someone else:

‘… You talk to someone and then you talk to someone else, and then you go and have like the pre-exam… And then you go and see the optician who’s someone else. And then you speak to the salesperson. So yeah, I find that very difficult. And I knew it was going to be like that, so I did put it off as long as I could.’27

Although probably efficient, autistic adults have expressed negative views about this type of system, feeling that it compromises their value as a patient:

‘…you’re part of some cattle production line. I find it very dehumanising.’27

Not only is constant change in staff discomforting, but so is having to visit multiple rooms because of the unfamiliarity with surroundings.

The mannerism of practice staff also affects how at-ease autistic individuals feel during this journey. Staff should be aware that autistic people can become easily overwhelmed. Constantly attending to them, especially during the spectacle dispensing phase, and offering multiple optional extras is stress-inducing. Autistic people have expressed:

‘… The woman is standing there staring at me while I’m trying to choose these specs. Well, anything that overloads my head, my brain just shuts down then … I have to take my wife everywhere and she has to tell them to go away.’27

Continuity of practitioner

Staff continuity is important across successive eye examinations for autistic adults, especially of the optometrist. Seeing the same optometrist allows autistic adults to feel relaxed and respond better because they know the practitioner. The practitioner would also have built a relationship with the autistic patient over a series of examinations, and therefore better understand their requirements. Overall, autistic people feel more confident with an optometrist that they see regularly, regardless of the practitioner’s competence.

Eye examination-specific issues

Practitioner to patient communication

Poor communication, understanding and trust distresses autistic adults during clinical appointments.38 Therefore, the rapport created by optometrists strongly influences eye care accessibility:

“…the interpersonal interaction greatly outweighs anything I have to do inside…”27

The quality of communication plays a large part in this, which autistic adults have said needs improvement. Communication should be adapted so that autistic adults feel comfortable, can process what they are being told, and clearly understand instructions and procedures. But this is a fine balancing act with sounding patronising and speaking to autistic patients in a child-like manner. The communication improvements indicated by autistic adults are what would be usually expected of an optometrist in the College of Optometrists’ ‘partnership with patients’ professional guidelines.39

Autistic adults have emphasised the positive impact of optometrists simply introducing themselves, and being attentive, understanding and reassuring. This makes them feel more confident around the optometrist and with the different tests. An eye examination assesses many aspects of ocular functions, be it refractive error, ocular muscle balance or eye health. Autistic people feel anxious when they are unsure of what to expect. They have expressed concern around the lack of information given about the individual eye tests, what would be involved and the importance of each. As a result, the significance of eye examinations conducted by an optometrist has been questioned, especially if a ‘machine has already done it.’27

Autistic adults can think very literally40 and may only provide relevant information if specifically asked.22 Therefore, they have highlighted that optometrists’ instructions and questions need to be more robust, especially for subjective tests:

‘I don’t want to anticipate, but I wish the language was more concrete.…don’t ask me what’s better, ask me is it supposed to be sharper or brighter or something.’27

Generally, optometrists need to be clearer on what should be judged by the patient during subjective tests, and mention if no difference or improvement in vision should be expected. For example, during cross-cylinder assessment, optometrists commonly ask ‘are the circles rounder and sharper with lens one or two?’ An autistic patient may interpret this as there must be a difference between the two options, subsequently becoming distressed if they are not noticing it:

‘I’m obviously doing something wrong because I can’t see the difference.’27 Rather, the optometrists should ask ‘are the circles rounder and sharper with lens one or two, or about the same?’

After an eye examination, some autistic adults have described feeling unsure of the outcomes, and if their vision and eye health are within normal limits. Autistic adults have expressed anxiety about normal ocular phenomena, such as the time taken to adapt to different light levels and physiological floaters. It could be the case that optometrists insufficiently address such presenting concerns knowing that they are normal. However, if these concerns are troubling an autistic person on a daily basis, they can come away from an eye examination feeling worried and frustrated.

Eye tests, sensory issues and anxiety

The uniform structure, together with the variety of tests and gadgets used during an eye examination creates an interesting experience for some autistic adults. But for others, it can be a very distressing process:

‘I actually feel like I want to cry sometimes because I’ve had to work so hard.’27

Autistic adults have described subjective eye tests as the most difficult part of an eye examination. This is not helped by them sometimes feeling rushed. They feel under pressure, worrying that any incorrect responses will jeopardise the examination outcomes, particularly the spectacle prescription. Research has confirmed that autistic adults can have difficulty with decision-making,41 so it is unsurprising that they find tests that involve lens comparison challenging. Because of the concentration and numerous responses required autistic adults can end up feeling overwhelmed, leading to a point where they cannot answer anymore.

Due to the sensory challenges and anxiety that autistic adults are prone to, certain eye tests can be extremely unpleasant. In particular, tests involving a sudden occurrence, such as non-contact tonometry (commonly known as the ‘air-puff test’), are very distressing and cause spikes in anxiety during the examination. Furthermore, tests requiring close proximity (e.g., direct ophthalmoscopy) or having to sit behind a slit-lamp on a combi unit feel incredibly uncomfortable, giving a sense of being trapped. Considering the sensory issues that autistic adults experience,42 tests involving bright lights, a flash of light or skin contact are challenging. Additionally, practitioners wearing strong perfumes can be very distracting. Autistic adults have to work extra hard to override the consequences of sensory issues and be able to attend to tests.

Key messages

Autistic adults face a number of barriers when accessing eye examinations. These begin from the point of booking the examination, to arriving at the practice, and undergoing multiple tests with different staff members. These barriers create anxiety and stress. As a result, autistic adults can avoid eye care. It is obvious that when considering how to improve eye care accessibility for autistic people, providers need to take a holistic approach.

This article raises the key concerns that autistic adults have about eye care services. Considering the variety of tests employed by an optometrist and how this could pose challenges for autistic adults, the next article in this series will detail more eye examination-specific feedback. In the final article, we will bring together the learnings from this series and discuss some easy-to-implement adaptations for autism-friendly eye care.

- Dr Ketan Parmar is a research optometrist at Eurolens Research, and Optometry Clinical Tutor for the undergraduate Optometry degree programme at The University of Manchester.

References

- Anketell P, Saunders K, Gallagher S, Bailey C, Little J. Brief report: Vision in children with autism spectrum disorder: What should clinicians expect? Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2015;45(9):3041-7.

- Gowen E, Porter C, Baimbridge P, Hanratty K, Pelham J, Dickinson C. Optometric and orthoptic findings in autism: a review and guidelines for working effectively with autistic adult patients during an optometric examination. Optometry in Practice. 2017;18(3):145-54.

- Little JA. Vision in children with autism spectrum disorder: a critical review. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2018;101(4):504-13.

- Parmar KR. An investigation of optometric and orthoptic conditions in autistic adults [PhD]. Manchester: The University of Manchester; 2022.

- Evans BJW. The need for optometric investigation in suspected Meares–Irlen syndrome or visual stress. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics. 2005;25(4):363-70.

- Evans BJW, Allen PM. A systematic review of controlled trials on visual stress using Intuitive Overlays or the Intuitive Colorimeter. Journal of Optometry. 2016;9(4):205-18.

- Whitaker L, Jones C, Wilkins A, Roberson D. Judging the intensity of emotional expression in faces: the effects of colored tints on individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research. 2016;9(4):450-9.

- Anketell P, Saunders K, Gallagher S, Bailey C, Little J. Profile of refractive errors in European Caucasian children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder; increased prevalence and magnitude of astigmatism. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics. 2016;36(4):395-403.

- Ezegwui I, Lawrence L, Aghaji A, Okoye O, Okoye O, Onwasigwe E, et al. Refractive errors in children with autism in a developing country. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice. 2014;17(4):467-70.

- Scharre JE, Creedon MP. Assessment of visual function in autistic children. Optometry and Vision Science. 1992;69(6):433-9.

- Anketell P, Saunders K, Gallagher S, Bailey C, Little J. Accommodative Function in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Optometry and Vision Science. 2018;95(3):193-201.

- Black K, McCarus C, Collins MLZ, Jensen A. Ocular manifestations of autism in ophthalmology. Strabismus. 2013;21(2):98-102.

- Denis D, Burillon C, Livet M, Burguiere O. Ophthalmologic signs in children with autism. Journal francais d’ophtalmologie. 1997;20(2):103-10.

- Ikeda J, Davitt BV, Ultmann M, Maxim R, Cruz OA. Brief report: incidence of ophthalmologic disorders in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(6):1447-51.

- Kabatas E, Ozer P, Ertugrul G, Kurtul B, Bodur S, Alan B. Initial ophthalmic findings in Turkish children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45(8):2578-81.

- Milne E, Scope A, Griffiths H, Codina C, Buckley D. Brief Report: Preliminary Evidence of Reduced Sensitivity in the Peripheral Visual Field of Adolescents with Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(8):1976-82.

- Wang J, Ding G, Li Y, Hua N, Wei N, Qi X, et al. Refractive Status and Amblyopia Risk Factors in Chinese Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2018;48(5):1530-6.

- Graham P. Epidemiology of strabismus. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1974;58(3):224.

- Fu Z, Hong H, Su Z, Lou B, Pan C-W, Liu H. Global prevalence of amblyopia and disease burden projections through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020;104(8):1164.

- Milne E, Griffiths H, Buckley D, Scope A. Vision in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorder: Evidence for reduced convergence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39(7):965-75.

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, McDonald K, Dern S, Boisclair WC, Ashkenazy E, et al. Comparison of healthcare experiences in autistic and non-autistic adults: a cross-sectional online survey facilitated by an academic-community partnership. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28(6):761-9.

- Dern S, Sappok T. Barriers to healthcare for people on the autism spectrum. Advances in Autism. 2016;2(1):2-11.

- Christou E. A Spectrum of Obstacles: an enquiry into access to healthcare for autistic people. Huddersfield: The Westminster Commission on Autism; 2016.

- Sala R, Amet L, Blagojevic-Stokic N, Shattock P, Whiteley P. Bridging the Gap Between Physical Health and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2020;16:1605-18.

- SeeAbility. Resources [internet]. SeeAbility; 2019. [Accessed 14 March, 2022]. Available from: https://www.seeability.org/resources?resource_specialism=52

- The College of Optometrists. Examining patients with autism. The College of Optometrists; 2021. [Accessed 14 March, 2022]. Available from: https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/guidance/knowledge,-skills-and-performance/examining-patients-with-autism

- Parmar KR, Porter CS, Dickinson CM, Baimbridge P, Pelham J, Gowen E. Autism-friendly eyecare: Developing recommendations for service providers based on the experiences of autistic adults. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics. 2022;42(4):675-93.

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases. 11th Revision ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- Dusheiko M, Gravelle H. Choosing and booking—and attending? Impact of an electronic booking system on outpatient referrals and non-attendances. Health Economics. 2018;27(2):357-71.

- Coulter RA, Bade A, Tea Y, Fecho G, Amster D, Jenewein E, et al. Eye examination testability in children with autism and in typical peers. Optometry and Vision Science. 2015;92(1):31.

- Krieger B, Piškur B, Schulze C, Jakobs U, Beurskens A, Moser A. Supporting and hindering environments for participation of adolescents diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. PloS one. 2018;13(8):e0202071.

- NHS England. Accessible information standard – overview 2017/2018. Leeds: NHS England; 2017. [cited 07 August 2022]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/accessible-info-standard-overview-2017-18.pdf

- 33Healthwatch Suffolk. Accessible information: Our poster about your rights. Suffolk: Healthwatch Suffolk; 2022. [cited 07 August 2022]; Available from: https://healthwatchsuffolk.co.uk/news/aisposter/

- Cermak SA, Duker LIS, Williams ME, Dawson ME, Lane CJ, Polido JC. Sensory adapted dental environments to enhance oral care for children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45(9):2876-88.

- Simpson S. Checklist for Autism-Friendly Environments. Kirlees: South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust; 2015 [cited 07 August 2022]; Available from: https://www.southwestyorkshire.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014 /10/Checklist-for-autism-friendly-environments.pdf

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM, Ashkenazy E, McDonald KE, Dern S, Baggs AE, et al. “Respect the way I need to communicate with you”: Healthcare experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism. 2015;19(7):824-31.

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, McDonald K, Kapp S, Weiner M, Ashkenazy E, et al. The development and evaluation of an online healthcare toolkit for autistic adults and their primary care providers. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2016;31(10):1180-9.

- Saqr Y, Braun E, Porter K, Barnette D, Hanks C. Addressing medical needs of adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders in a primary care setting. Autism. 2018;22(1):51-61.

- The College of Optometrists. Partnership with patients. The College of Optometrists; 2022 [Cited 07 August 2022]; Available from: https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/guidance/communication,-partnership-and-teamwork/partnership-with-patients#Keypoints

- Mason D, Ingham B, Urbanowicz A, Michael C, Birtles H, Woodbury-Smith M, et al. A Systematic Review of What Barriers and Facilitators Prevent and Enable Physical Healthcare Services Access for Autistic Adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2019;49(8):3387-400.

- Luke L, Clare ICH, Ring H, Redley M, Watson P. Decision-making difficulties experienced by adults with autism spectrum conditions. Autism. 2012;16(6):612-21.

- Green D, Chandler S, Charman T, Simonoff E, Baird G. Brief report: DSM-5 sensory behaviours in children with and without an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(11):3597-606.