The profile of vision care for patients with special needs has been raised considerably over the past decade as healthcare commissioners and practitioners adapt to demographic changes in the population and legislation such as the UK Equality Act 2010. Domiciliary eye care for patients who cannot leave home under their own steam is a growing aspect of eye care practice and new services, such as the Special School Eye Care Service, which was first adopted in Wales and has more recently been rolled out in some parts of England, have demanded new skills from the practitioners involved.

Epidemiology of Disability in the UK

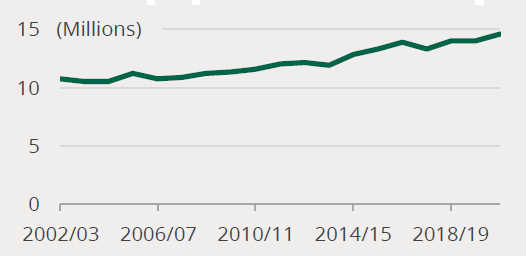

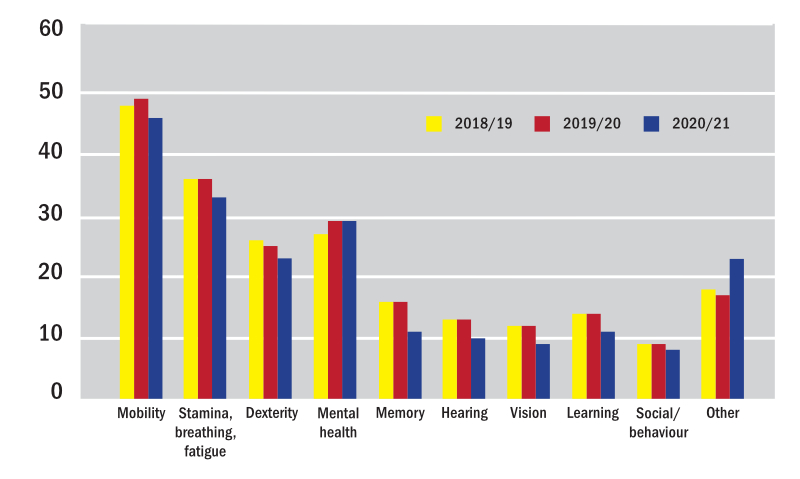

According to House of Commons research, drawing on many sources, the number of patients with special needs due to learning difficulties, autism and other disabilities is increasing in number steadily in the UK (figure 1) and this is mirrored throughout the developed world. According to a recent survey,1 between one in five and one in four UK citizens consider themselves to be disabled. This represents 14.6 million people (around 22% of the population), of whom over five million are entitled to additional benefits because of the increased living costs associated with their disability.

Figure 1: The number of people living with a disability in the UK is increasing1

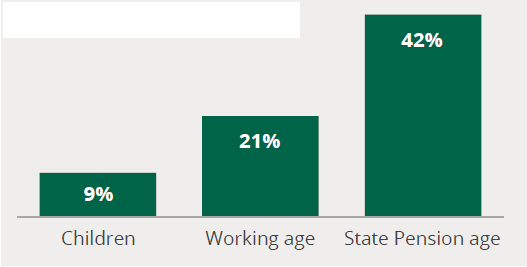

The prevalence of disability rises with age. Some 9% of children live with disability compared to 22% of people of working age and 42% of adults over state pension age, rising to 59% in the over-80s (figure 2). Elderly patients make up a significant percentage of sight tests and dispensing in community optical practices, and the overwhelming majority of domiciliary eye care visits. Despite advances in healthcare, as a result of the post-Second World War baby boom, disability is steadily increasing with comorbidity, where a person lives with several disabilities and/or chronic conditions, also increasing dramatically as people live longer.

Figure 2: Proportion of people living with a disability in the UK by age group1

Disability in Children

The fact that disability in children is increasing steadily is worth noting. This increase is undoubtedly partly due to increased testing and diagnosis, particularly of learning difficulties and autistic spectrum disorders. However, it is also partly driven by increased prevalence of congenital abnormalities. The most common severe congenital abnormalities are heart defects, neural tube (embryonic spinal cord and brain) malformation, and Down’s syndrome.2 The increased prevalence of these and many less serious birth defects is partly because women in developed nations now choose to have children later in life than in previous times and age is a known risk factor.

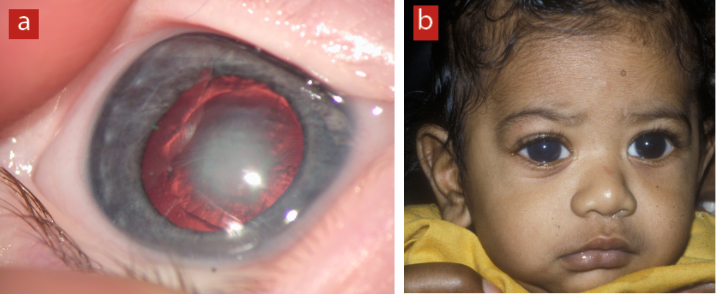

Reduced uptake in the 14 or so childhood immunisation programmes from the 1990s onwards is filtering through to increased prevalence of diseases such as rubella during pregnancy leading to increased rates of conditions with lifelong consequences. For example, congenital rubella syndrome (CRS), if the baby survives at all, can cause many potentially disabling conditions including deafness, cataracts, heart defects, intellectual disabilities, glaucoma and brain damage (figure 3).

Figure 3: Reduced uptake of childhood immunisation programmes has resulted in increases in eye defects such as (a) congenital cataract and (b) congenital glaucoma

Childhood immunisation is an important aspect of public health and has saved hundreds of millions of lives. Public health concerns the organised efforts of society to prevent disease and promote health and well-being and vaccination is an important part of public health policy given that most conditions for which children routinely receive immunisation have no cure, few treatment options, and significant risk of lifelong disability. For this reason, eye care practitioners (ECPs) have an important public health role convincing parents and patients of the value of vaccinating their children when it is clear that they do not feel vaccination is of any benefit. It is incumbent upon ECPs, who are themselves sceptical about vaccination, to urgently review the scientific evidence in order that they align themselves with the current medical and scientific evidence that they are expected to reflect as registered healthcare practitioners.

The recent anti-vax movement has discouraged many parents from having their children vaccinated against the usual childhood diseases, so infections, such as measles, which had largely been eradicated from the UK, are now making a comeback with devastating consequences for the young children unfortunate enough to contract them, who often subsequently have to live with lifelong disability.

Impact of Disability

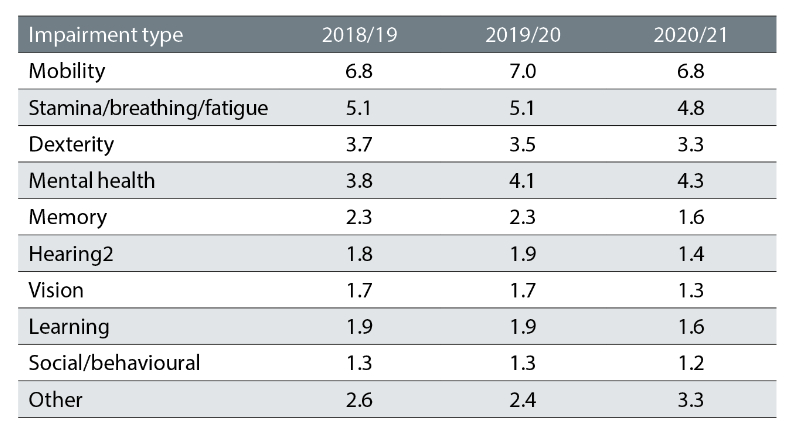

The Equality Act 2010 defines a disability as a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities. The exact nature of the underlying impairment leading to the disability varies considerably and, as mentioned earlier, it is common for individuals to have more than one disability. Table 1 summarises some recent figures of the numbers of people in the UK with specific impairments, while figure 4 shows the percentage of disabled people with different types of impairment.

Table 1: Numbers of disabled people (in millions) reporting different types of impairment3

Figure 4: Percentage of people with a disability with a range of impairments. Remember that many disabled people will have more than one impairment

Learning Disability

Mencap defines a learning disability as reduced intellectual ability and difficulty with everyday activities, for example, household tasks, socialising or managing money, and which affects someone for their whole life. Calculated using learning disability prevalence rates from Public Health England (2016) and population data from the Office for National Statistics (2019), the estimated prevalence of learning disabilities in children in the UK is 2.5%. In England, currently, it is estimated that 79% of children with severe learning disabilities and 81% of children with profound and multiple learning disabilities attend special schools. This amounts to more than 120,000 children.4

Many people with a learning disability may have an associated general health diagnosis, which increases the risk of ocular or visual problems. Adults with a learning disability are 10 times more likely to have an eye or vision problem5 and, for children, this increases to a staggering 28 times. By contrast, sight problems are comparatively rare in the general paediatric population.6 Due to this increased risk of both visual and ocular problems, it is important that regular and tailored eye care is available and accessible for all children with a learning disability.7

Reasonable Adjustments to Eyecare Practice

The Equality Act 2010 recognises nine protected characteristics: age, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, sexual orientation, and disability (table 2). While discrimination against anyone on grounds of their protected characteristics is illegal, organisations, both as suppliers of services to consumers and as employers, only need to make so-called reasonable adjustments to accommodate the needs of disabled people.

Table 2: Nine protected characteristics under the Equality Act, 2010

- Age

- Gender Reassignment

- Marriage and Civil Partnership

- Pregnancy and Maternity

- Race

- Religion or Belief

- Sex

- Sexual Orientation

- Disability

Optical practitioners and businesses should consider what might constitute reasonable adjustments whenever they are making investments into the practice and in the light of their current and potential patient base. Whether opening a new practice, relocating or shopfitting existing premises, people with disability must be front of mind.

Many reasonable adjustments can be accommodated by using the principle of universal design, such that what benefits disabled service users also benefits many others. For example, ensuring a wheelchair-friendly environment also helps all other patients who struggle with stairs or narrow passages between displays, including parents using pushchairs or prams and customers with heavy luggage (or sales reps with heavy frame cases).

Case study – what is reasonable?

What constitutes a reasonable adjustment is largely common sense. However, it may ultimately be decided in a court of law if it becomes an issue. In the authors’ experience, planning authorities and NHS contract compliance teams take a dim view of practices seeking to cut corners in the accommodation of disabled patients and it is best to seek their advice in advance of starting work on new premises. For example, one practice was seeking to relocate to a new premises with substantial upstairs space to accommodate up to 12 consulting rooms and, although the practice had planned a downstairs test room, this was felt to give insufficient capacity for the number of sight tests provided to disabled patients. It also could not offer appointments for disabled contact lens or hearing aid patients, both of which were provided on behalf of the NHS. The practice was instructed to install a lift so that all rooms and services were accessible to all patients. However, planning permission was denied due to the fact that the building had listed status. After an expensive legal battle, the outcome was to relocate to a different premises altogether and install a lift.

So, when is it reasonable to install a lift? ‘Reasonable’ is a function of cost relative to affordability. Certainly, a practice is unlikely to be compelled to install a lift unless it is already undergoing shopfitting or relocation. However, larger practices with high levels of turnover and profitability will be compelled to ensure step-free access to all services. A very small practice that tests one or two days per week and turns over, say, £100,000 per year is likely to be able to argue that it is unreasonable to have to spend £50,000 on a lift. However, given that more than one in five people have some form of disability, a practice owner might want to consider if they can afford to alienate a substantial proportion of the population and a stair lift might be reasonable, as long as it does not create a hazard to others using the stairs.

That said, practices should not fall into the trap of thinking that disability is all about wheelchairs. In fact, only about 10% of disabled people use a wheelchair, around 1.9 million people in total (figure 5).8

Figure 5:

Table 3: Recommended reasonable adjustments for eye care practice

- Step free access to all services and departments

- Where a temporary ramp is used, this should be accessible from outside the practice by use of an intercom or other means of calling for staff assistance

- Wheelchair accessible consulting rooms

- Hearing aid loop (figure 6) at reception, pre-screening and selected dispensing desks and consulting rooms

- A choice of patient recall reminder communications including email, text message, telephone and large print letter

- Accessible website and marketing communications

Figure 6: Hearing aid loops are recommended throughout an eye care practice

Eye care practices and practitioners should consider making a number of reasonable adjustments to accommodate the needs of disabled people as listed in table 3. This list could easily apply to any business, and practices should not forget other obvious provision such as ensuring waiting area chairs have arms so that it is easier for elderly patients to stand up. Perhaps, the most obvious reasonable adjustment is for practices to be prepared to see all types of patients that should be within their scope of practice.

In the authors’ experience, many practices are unwilling to provide sight tests to pre-school children, especially those requiring cycloplegia, usually on the grounds that such children might not know their letters, or that the optometrists are not sufficiently proficient in retinoscopy. However, older patients with learning difficulties may also require similar techniques. Another group of patients that seem often to be unreasonably discriminated against are, surprisingly given the training of optometrists and dispensing opticians, those that are registered severely sight impaired.

Other reasonable adjustments therefore include:

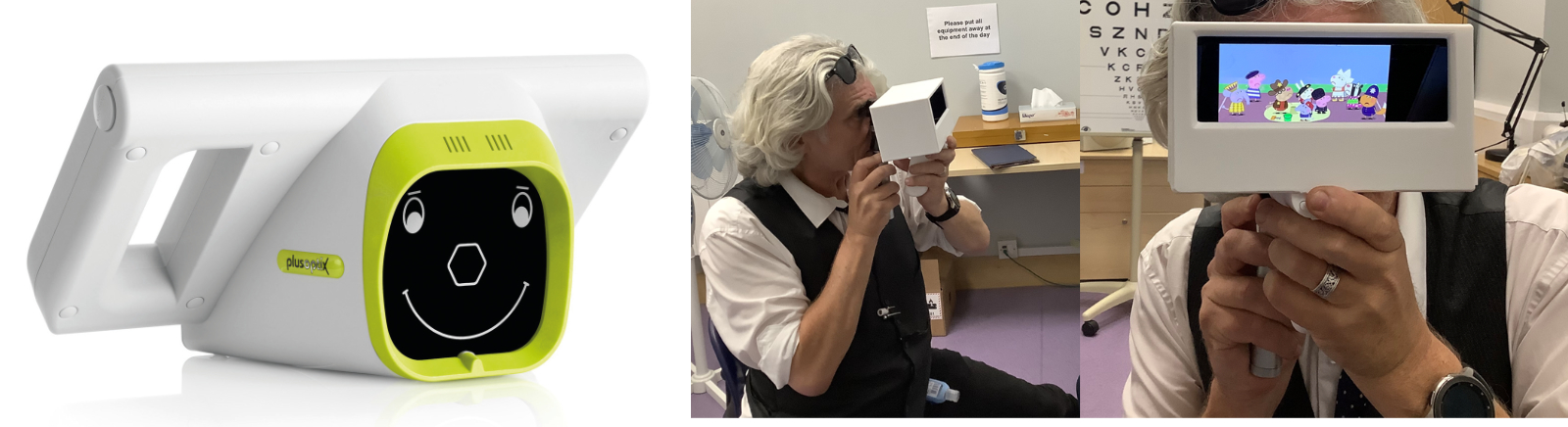

- Objective means of refraction: both retinoscopy and autorefraction. Some autorefractors are hand-held and incorporate features that help when assessing very young patients or those with learning disability (figure 7). A recent innovation is the Visual Fixation System, which allows retinoscopy via a two-way mirror onto which videos and images from a smartphone can be projected (figure 8).

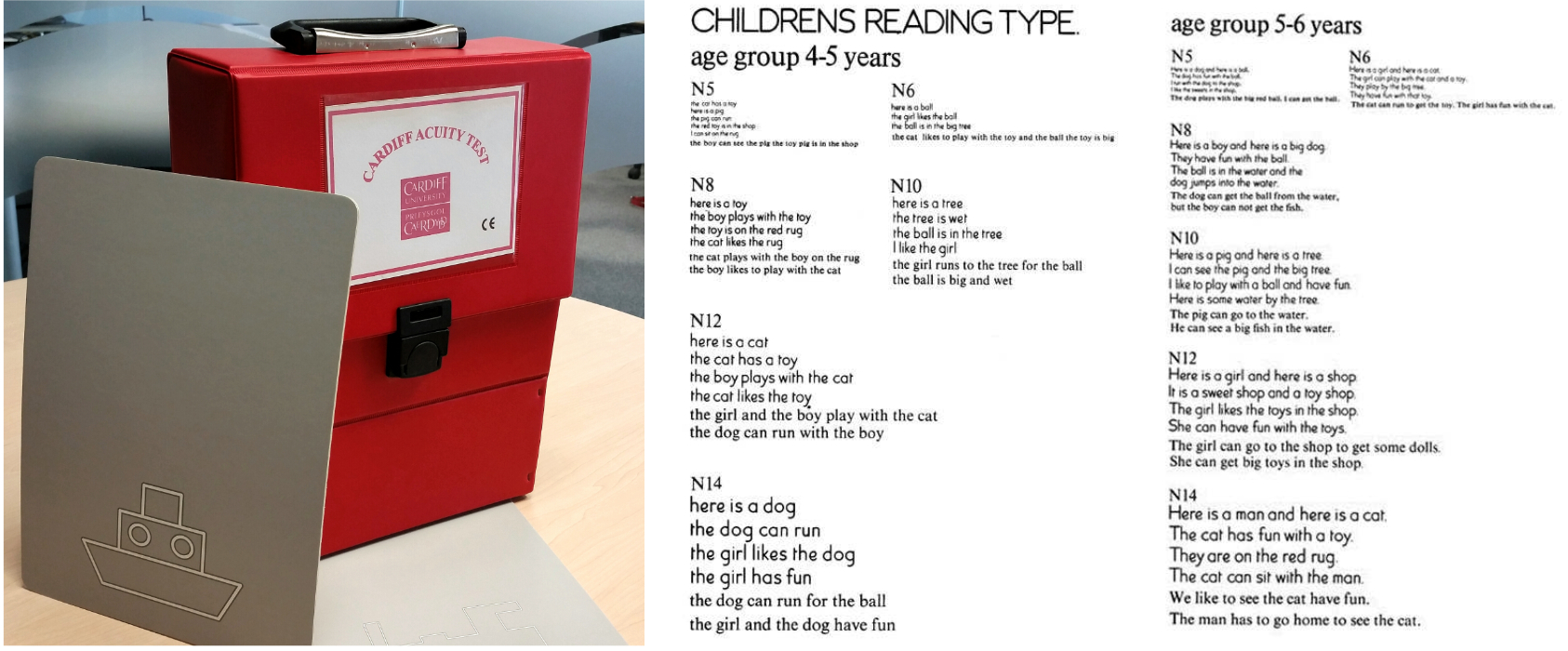

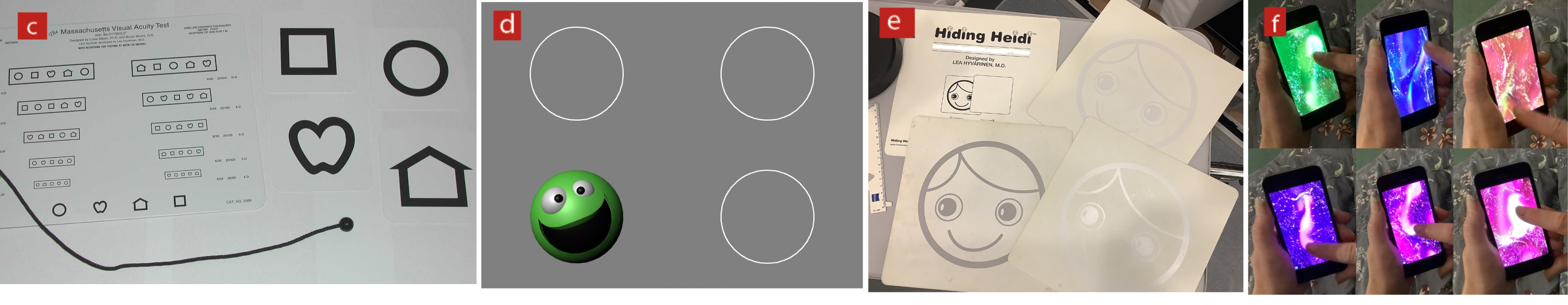

- Test charts suitable for patients of all ages and intellectual ability (figure 9)

- Test charts suitable for severely sight impaired patients and the ability to use them at reduced testing distances

Figure 7 & 8: Some hand-held autorefractors have adaptations to make assessment of children or those with learning disability more repeatable, such as the Plusoptix device shown; The Visual Fixation System for retinoscopy in use (left) and as seen by the patient (right)

Figure 9: Test charts for younger patients and those with learning disability. (a) Cardiff Acuity Test preferential looking cards. (b) McClure reading type test.

Figure 9: left-to-right (c) Massachusetts Acuity Charts. (d) Peek-a-boo app acuity test. (e) Hiding Heidi contrast test. (f) Sensory Plazma app displays

Given the right practice environment and suitable sight testing skills and equipment, there is still one other reasonable adjustment that must almost always be provided to patients with special needs; time.

It is not unreasonable to provide additional testing and dispensing time for patients who need it. However, time is also important in other ways. It is often beneficial when seeing patients in practice with special needs, including a learning disability, to invest time acclimatising them to the environment and procedures. This might include, for example, arranging for the patient and their carer to visit the practice independent of the sight test at a quiet time, to get to know the staff, practice layout and get used to some of the tests and trying on frames. Implicit in this is also accepting that it is often not possible to fully complete an examination and two or more appointments may be necessary to complete all that is required.

Special School Eye Care Service

The difficulty many patients with special needs have in coping with unfamiliar surroundings, and the fact that according to SeeAbility people with learning difficulties are 28 times more likely to live with serious sight problems, has led to the recent commissioning of the Special School Eye Care Service, firstly in Wales and, more recently, in many areas of England.

In England, this new service provides sight tests and the dispensing of spectacles if required on special school premises for the first time, providing an eye care service for the first time for the majority of the 100,000 pupils with a severe learning disability. The commissioning of the service follows a pilot where 45 of the first 200 children tested had significant undiagnosed vision problems including uncorrected refractive error, which had not been previously identified or addressed – this rate levelled off at 12.5% in a larger study.7,9 However, a staggering 46.2% of pupils had a visual deficit. Following the dispensing of spectacles, the pilot included observations of the child in the classroom environment to measure any change in learning and behaviour. Potentially, this now enables every learning-disabled student in these schools to be able to participate in the full education experience.

The charity SeeAbility, in conjunction with professional bodies such as ABDO, has developed tailored continuing professional development and training for dispensing opticians and optometrists. ABDO has also recently actively engaged with NHS England in the development of a new one-day training course for dispensing opticians that focused on dispensing for children with special facial characteristics.

In support of this service, NHS England has introduced a new dispensing order and supply model that does not require the use of GOS optical vouchers and enables ECPs to order spectacles from a comprehensive range of specialist frames without any commercial influence or consideration. This means ECPs can choose the most appropriate frames and lenses for every child and the invoicing process will be managed solely by NHS England.

Unfortunately, following a successful pilot, the service seems to be stuck in a ‘proof of concept’ stage and rollout has stalled, having only reached around 10% of schools (83 schools with under 10,000 pupils). Since funding is due for review in March 2023, sadly it appears likely that ECPs in most areas will likely need to see children and young adults with special needs in community practice rather than in the familiar school environment.10

Dispensing Considerations

Dispensing children and adults with special needs can be a real challenge, both technically and emotionally. However, there are strategies that can make it a successful and rewarding process.

Atypical facial features mean handmade frames or substantial adaptation of stock frames are much more likely. However, many of the skills required are similar to those used in paediatric dispensing generally that have been covered in previous articles (figure 12).11, 12 These include technical skills in terms of facial measurements and also communication skills required to put a patient at ease, develop a rapport and trust, and the ability to amuse the patient sufficiently so that important measurements can be taken quickly.

Figure 12: Communication skills are essential for paediatric dispensing

In general, patients with special needs are more likely to need robust spectacles, both in terms of the frame and the lenses. This is to ensure that they are fit for purpose for as long as possible and can withstand the rough and tumble that may accompany a special needs environment. Patients with special educational needs are likely to have mobility or coordination issues that make falls more likely, may have a condition that predisposes them to seizures or fits, or may simply behave erratically or violently on occasion. Practitioners should make safety a priority and, therefore, glass lenses are out of the question. CR39 lenses may be appropriate but are less impact-resistant than some alternatives. Polycarbonate lenses certainly offer excellent impact resistance.

However, the low Abbe number results in significant chromatic aberration and degradation of image quality. The best solution, therefore, is a lens made from 1.53 index plastic Trivex (also known as Trilogy or PNX) which offers good impact resistance and good image quality.

Many patients, including a significant proportion of those with Downs and a variety of other conditions, have poor accommodation and may need a reading addition at a young age. It is usual to dispense bifocals with a straight top segment set high, either on pupil centre or midway between pupil centre and lower limbus (figure 13). Where cooperation is troublesome, it may be easiest to draw the HCL and 2mm increments on the dummy lens of the frame and, assuming the patient is happy to keep the frame on, estimate the measurement by observing the frame in situ rather than trying to use a frame of face rule.

Figure 13: Nasir with his mother, soon after being fitted with bifocals7

Measurements can be difficult. However, many patients are intrigued by looking into machines and a pupillometer may offer more success than a ruler or iPad system for measuring the PD although, again, marking lines on a dummy lens and asking the patient to wear the frame may offer an alternative possibility of success.

Tints may be an appropriate option for many patients. These could include bespoke tints for patients with visual stress caused, for example, by dyslexia. Although this topic remains controversial due to a lack of robust evidence, there is no doubt that many patients report a benefit. Tints have been developed, however, that benefit specific conditions such as retinitis pigmentosa, albinism and specific types of colour vision deficiency.

Perhaps the biggest challenge with special needs patients is in frame choice. Many learning-disabled patients also live with significant physical disability and facial and other anatomical abnormalities that make standard frame fitting a challenge. Such abnormalities may include microtia, a congenital condition where the external cartilage of the ear is underdeveloped, or anotia (literally ‘no ears,’ where the pinna is absent); this may be bilateral or unilateral. External ear malformations and many other disabilities are often accompanied by hearing loss and the need for hearing aids, which provide for even more challenges from a frame fitting point of view (figure 14).

Figure 14: Adapting a frame to cater for ear malformation and a hearing aid (image courtesy of Jessica Gowing, Great Ormond Street Hospital)12

Frame fitting may also need to take into account padded wheelchair head restraints, helmets and other protective equipment.

It is difficult to generalise about specific conditions. However, the most common condition resulting in special needs is Downs syndrome and, while every Downs patient is unique, there is a tendency for short length to bend combined with relatively wide head width and low set ears and low crest height. Fortunately, specialist frames such as Erin’s World have been developed with Downs patients in mind and feature low set bridges, sides that can be shortened, and flexible components that spring back to shape.13

Many other frame companies offer children’s frames that are suited to children with special educational needs, including Centrostyle and Miraflex. Perhaps, the most well-known, and probably the most versatile, are Tomato frames (figure 15). These cater for sizes ranging from new-born babies to teenagers and small adults. They have the added advantage that they are supplied with a small toolkit to facilitate removal and refitting of the bridge at three different crest heights and also sides that can be shortened and come with elasticated head straps as standard. Such adaptation entitles the patient to a special facial characteristics GOS voucher making them much more affordable. Tiny frames are similarly subject to the small frame supplement, which is useful when dispensing babies and under-developed toddlers to ensure the patient gets the best frame for the job rather than what the parent can afford.

Figure 15: Tomato frame

Conclusion

Overall, special needs dispensing draws on all the skills of the dispensing optician; critical thinking, measurement, communication and, perhaps above all, the ability to solve problems through excellent knowledge of what is available and what is possible. This includes knowledge of repair services, companies that can adapt frames to fit atypical facial features, sources of repair parts to make such adaptations possible in practice and knowledge of specialist frames that are purpose-designed to meet the needs of patients living with specific disabilities such as Downs.

However, before that can happen, practitioners need to get involved with services where they are commissioned; in the absence of such commissioned services, make sure reasonable adjustments are made in practice to ensure this important group of patients get the eye care services they deserve and need.

- Peter Black MBA FBDO FEAOO AFHEA is Course Lead for BSc (Hons) Ophthalmic Dispensing at the University of Central Lancashire, Preston, and is a practical examiner, practice assessor, exam script marker, board member and past president of the Association of British Dispensing Opticians.

- Tina Arbon Black BSc (Hons) FBDO CL is director of accredited CPD provider Orbita Black Limited, an ABDO practical examiner, practice assessor and exam script marker, and a distance learning tutor for ABDO College.

Useful resources

- SeeAbility online resources. Available at: www.seeability.org/resources

- Ulster University Vision Resources CVI Strategies for 9-12 year olds. Available at: https://www.ulster.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/168245/cvi-strategies-at-school-9-12yrs.pdf

- Ulster University Vision Resources CVI Strategies for 4-8 year olds. Available at: https://www.ulster.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/168221/cvi-strategies-at-home-4-8yrs.pdf

- Manchester University resources for autistic patients to help them prepare for an eye examination (which eye care providers can freely use), and recommendations for eye care providers for autism-friendly services. Available at: https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/autism-and-vision

References

- UK disability statistics: Prevalence and life experiences. UK Government, downloadable at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9602/

- World Health Organisation fact sheets: birth defects. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/birth-defects

- www.gov.uk/government/statistics/family-resources-survey-financial-year-2020-to-2021

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/804374/Special_educational_needs_May_19.pdf

- Emerson E, Robertson J. The estimated prevalence of visual impairment among people with learning disabilities in the UK. RNIB SeeAbility [Internet]. 2011;35. Available from: http://www.rnib.org.uk/aboutus/Research/reports/2011/Learn_dis_small_res.pdf

- Das M, Spowart K, Crossley S, Dutton GN. Evidence that children with special needs all require visual assessment. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2010;95(11):888–92

- Rughani S, Donaldson L. Eye care for children with learning disabilities – 1. Epidemiology and the case for a national programme of eye care. Optician, 15.06.2020, pp17-23

- https://www.disabled-world.com/disability/statistics/wheelchair-stats.php

- Donaldson LA, Karas M, O’Brien D, Woodhouse JM. Findings from an opt-in eye examination service in English special schools. Is vision screening effective for this population? Awadein A, editor. PLoS One. 2019 Mar;14(3):e0212733

- www.specialneedsjungle.com/nhs-england-breaking-promise-eye-care-for-disabled-children-all-special-schools

- Rughani S, Donaldson L. Eye care for children with learning disabilities – 3. Outcomes of eye examinations and dissemination of information. Optician, 19.02.2021, pp23-29

- Gowing J. Paediatric eye care — part 1. Paediatric dispensing. Optician, 17.11.2017, pp20-27

- https://erinsworldframes.com