A s the clock counted down to the start of the 2023 CooperVision Virtual Perspectives conference, thousands of eye care professionals (ECPs) from across the globe signed in to hear the latest research and opinions about myopia management (figure 1). During the day, academic double act and event hosts Professors Lyndon Jones and Philip Morgan (figure 2) introduced a session delivered by Professor James Wolffsohn (Aston University) and Professor Debbie Jones (University of Waterloo), which focused on the significance and impact of increasing levels of myopia across the world and showed how clinical practice is necessarily adapting to address the problems this increase presents.

This article aims to highlight the key points that might be relevant to ECPs in primary care in the UK.

Figure 1: Countdown to conference

Figure 2: Hosts, Professor Lyndon Jones (left) and Professor Philip Morgan

Myopia Epidemiology

The figures for the prevalence of myopia and its increasing incidence over the past few decades are as remarkable as they are worrying. This was clearly outlined at the start of the session by Professor Debbie Jones who firstly reminded the audience of the myopia figures, oft-quoted in previous decades, published by Professor Sorsby in the 1950s. As national service was still in force in the UK, figures were collated of the number of myopes among 1,017 men, aged 17 to 27 years, with non-emmetropic eyes and found to have ‘a dysregulation’ of emmetropia. In other words, those with what appeared to be progressive myopia. The figure for this group was found to be just 13%, a group who were described as having some form of ‘failure of homeostasis’.1

Concern was first aroused about the growing incidence of myopia when data from the Far East emerged from the 1980s onwards. Researchers, such as Lin et al, started publishing data showing an 84% prevalence for myopia among Taiwanese schoolchildren (of a sample of 11,000 16 to 18-year-olds).2 In 2012, a prevalence of 96.5% for myopia was found among 19-year-old South Korean conscripts aged 19 years (n=23,616).3

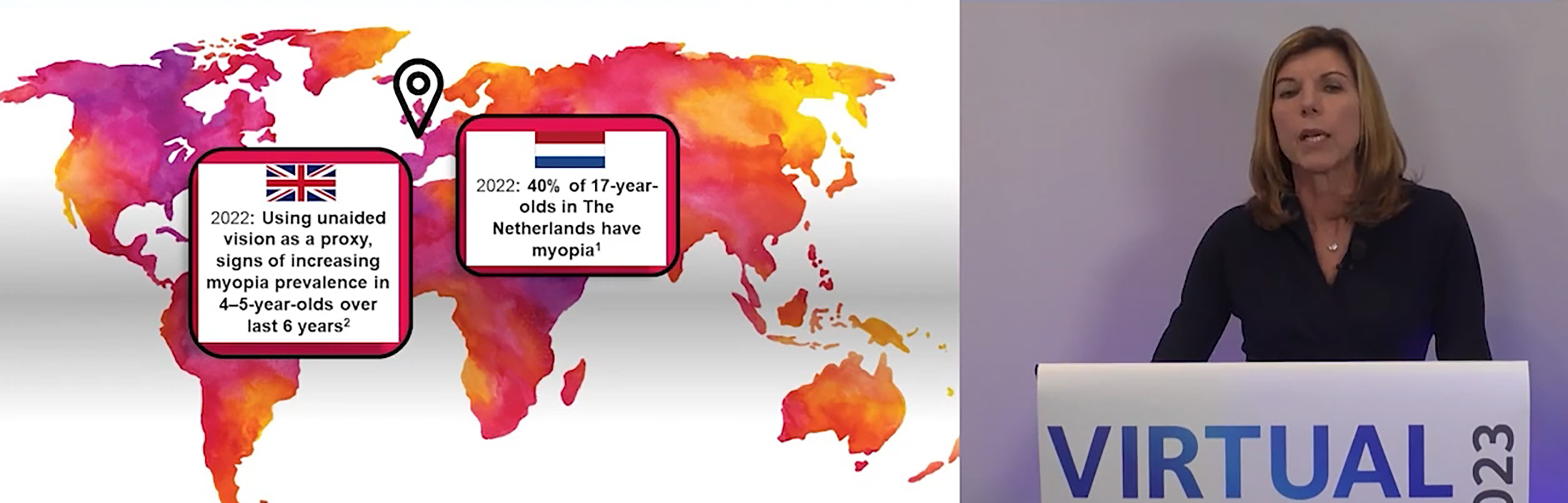

But, as Prof Jones pointed out, the West is hardly immune to the growth of myopia as many had once been tempted to believe (figure 3). Figures presented at the 2022 Myopia Conference in Rotterdam showed how 40% of 17-year-olds in the Netherlands now have myopia while, in the UK, myopia prevalence among four to five-year-olds is now confirmed as being on the increase.

Figure 3: Professor Debbie Jones presenting myopia growth data from Europe

Association with Visual Impairment

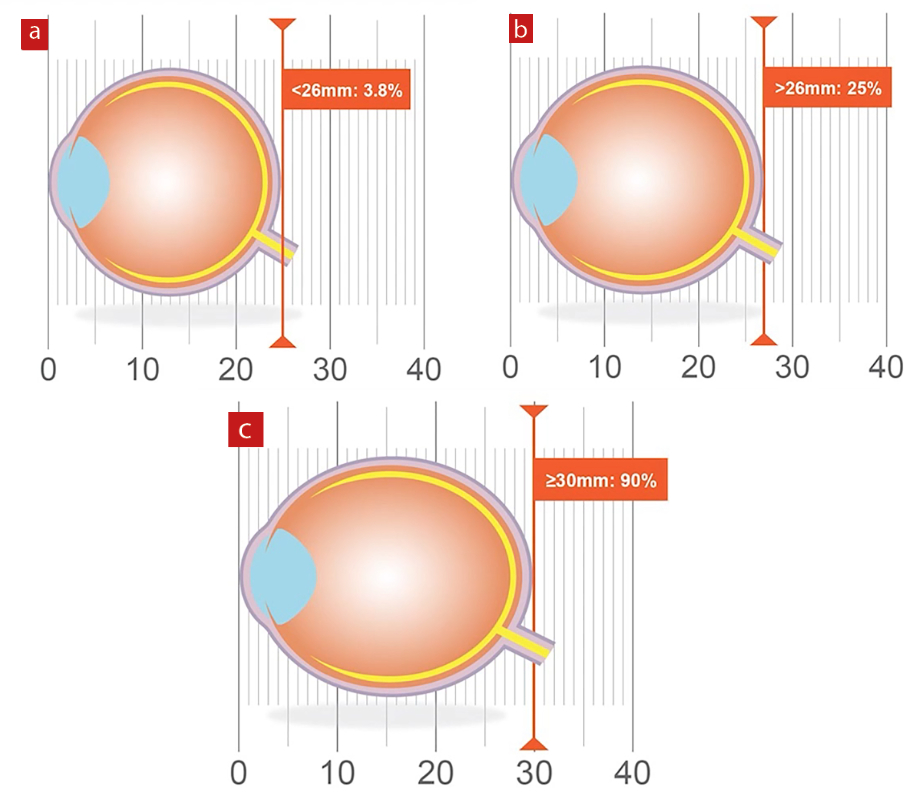

Professor Jones followed up the population statistics with an excellent schematic representation of the association between increased axial length and increased risk of uncorrectable visual impairment (VI). Referring to the work of Tiderman et al,4 she suggested that a ‘normal axial length of under 26mm has a likelihood of development of VI of 3.8%. This risk increases dramatically, however, with axial length of greater than 26mm having a VI risk of 25%, which, for lengths of more than 30mm, increases to a shocking 90% (figure 4).

Figure 4: The association of axial length with % risk of uncorrectable visual impairment for (a) <25mm, (b) >25mm and (c) >30mm (after Tiderman et al4)

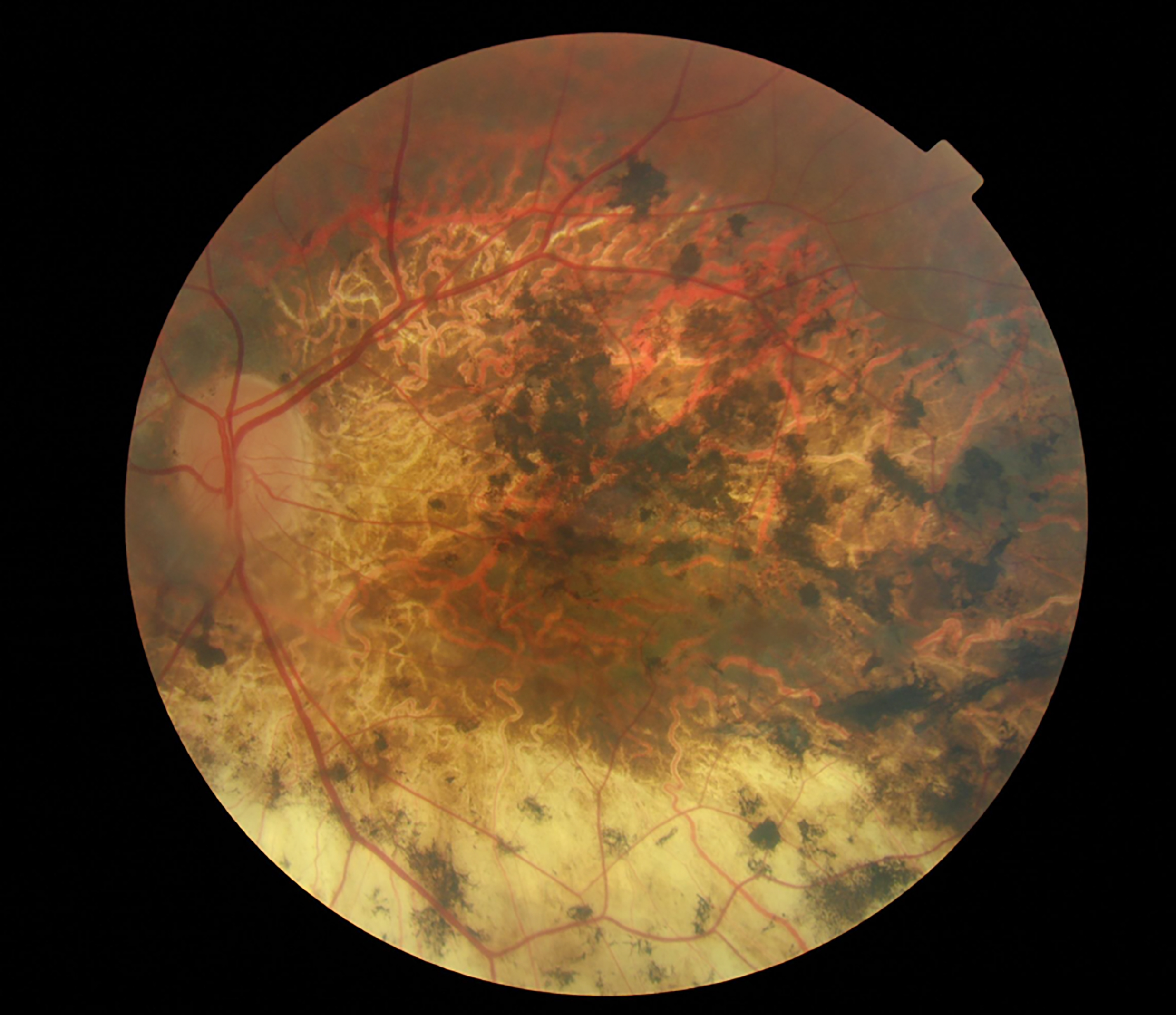

The causes of uncorrectable VI include retinal detachment, cataract, glaucoma and, most significantly of all, myopic maculopathy (figure 5). This has led to efforts by researchers to quantify the risk of maculopathy with increasing myopia. Perhaps best known of these is the work by Professor Mark Bullimore who coined the now well-quoted statistic that ‘each dioptre matters’. Put more specifically, every increase of -1.00DS myopia increases the prevalence of myopic maculopathy by 58%. And, for those doubting the benefits of myopia management: every reduction of myopia by 1.00DS is associated with around 40% reduction in the risk of myopic maculopathy.5

Figure 5: Extensive myopic maculopathy in a patient registered as severely sight impaired

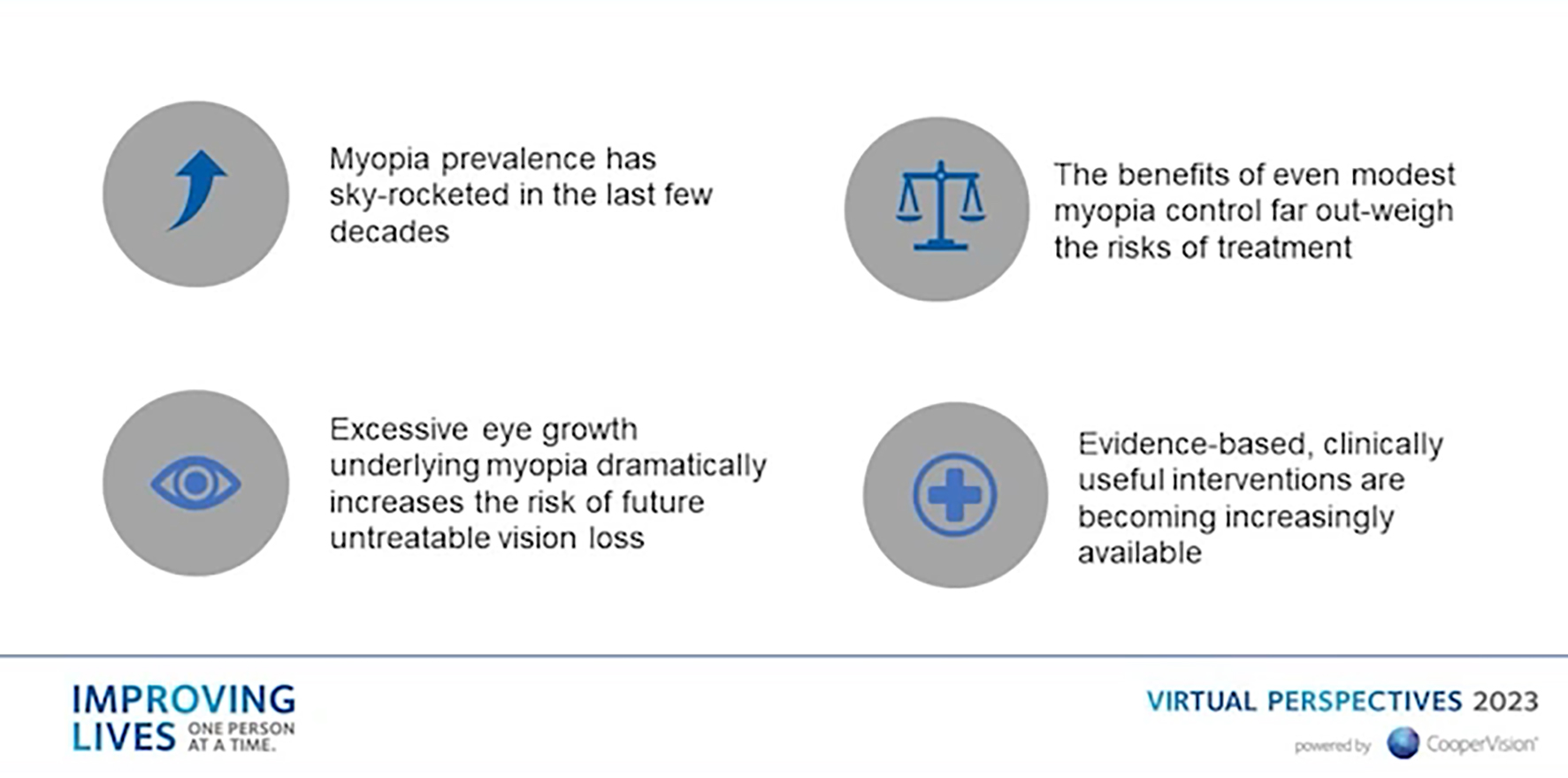

The extent and significance of increasing myopia levels is summarised in the slide shown in figure 6.

Figure 6: Summary of the relevance of myopia data

In summary, Professor Jones suggested that ‘it is our duty to keep axial length as short as possible.’

International Myopia Institute (IMI)

Introducing the work of the International Myopia Institute (IMI), Professor James Wolffsohn reminded delegates of the first IMI session that was held at Aston University back in 2017 (figure 7). First set up in 2015 following a World Health Organisation and Brien Holden Vision Institute (BHVI) meeting on myopia and high myopia, the IMI has set out several aims as summarised in table 1.

Table 1: Overall aims of the IMI

Figure 7: Professor James Wolffsohn and the first IMI meeting at Aston University

Prof Wolffsohn then described the timeline of IMI activities, including the two key publications of IMI papers in 2019 and 20216 and the creation of the IMI Facts and Findings Infographic (in multiple languages), a useful public health communication tool and chairside reference of key myopia management evidence-based information easily accessed by practitioners.7

Professor Wolffsohn then told of the forthcoming 2023 publication soon to be made available. His specific topic within the new papers includes the results from a global practitioner survey on the uptake of myopia management. As ECPs, knowing how our profession is evolving globally is important and new trends in practice based on clinical evidence should be understood by all.

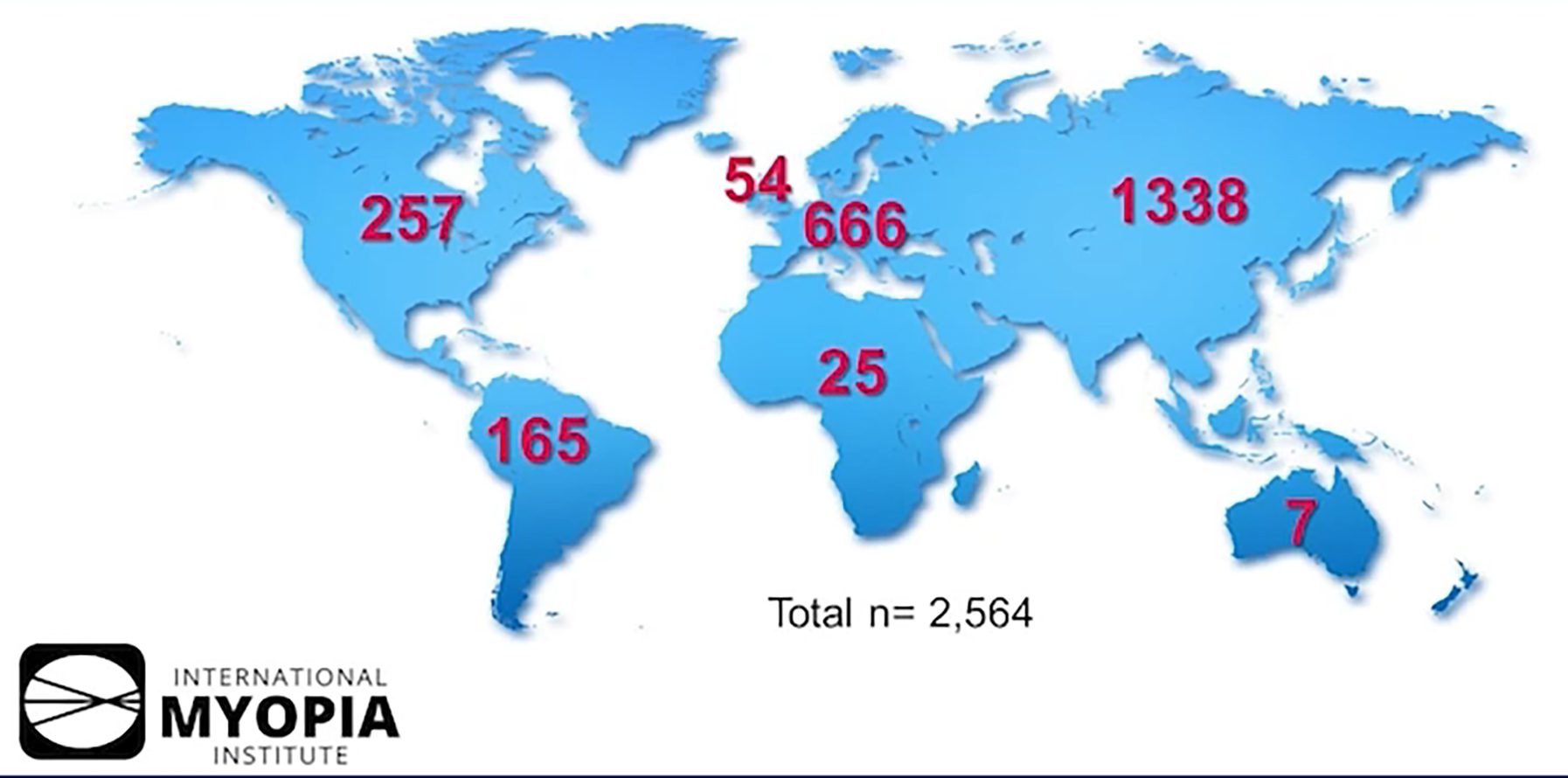

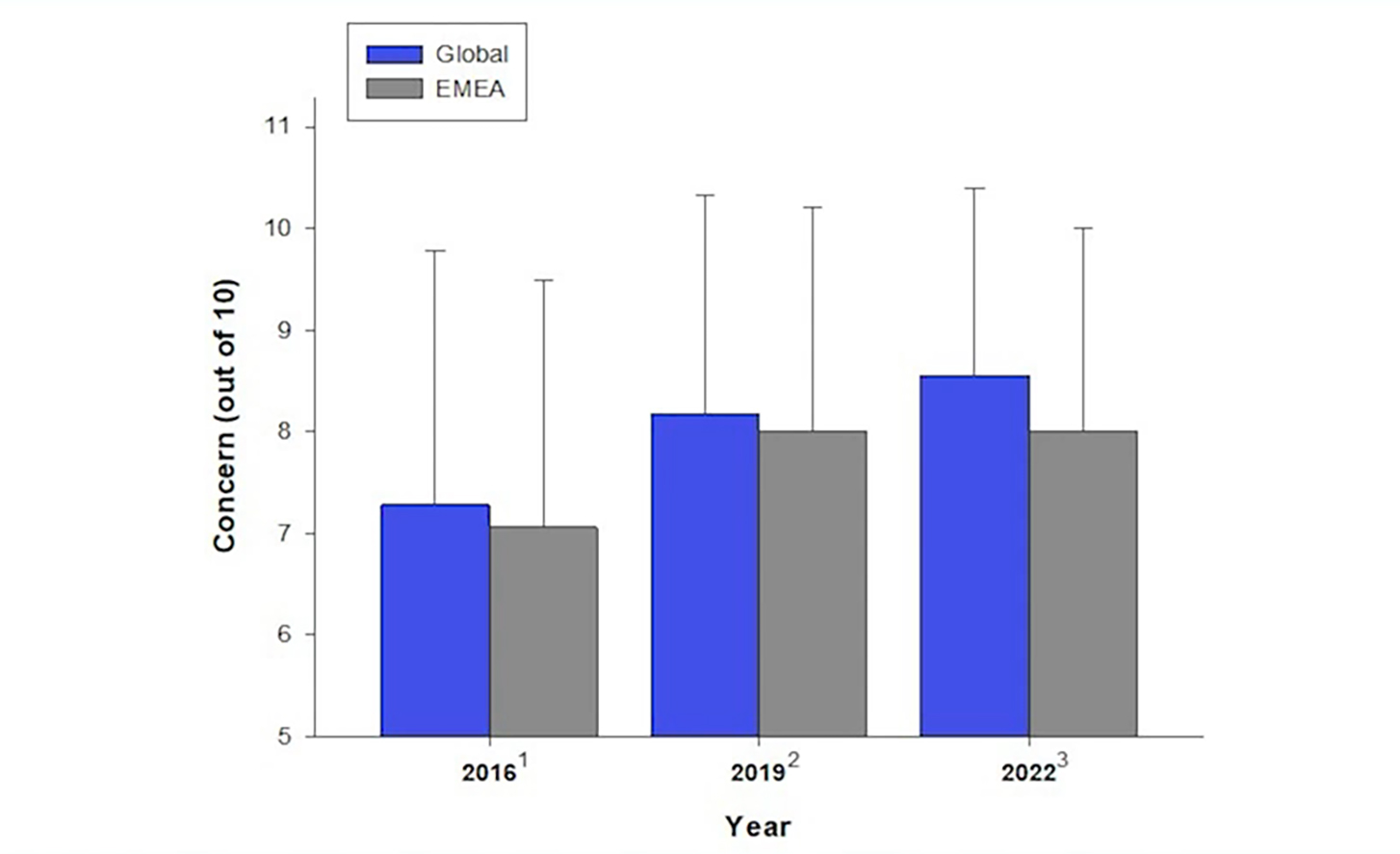

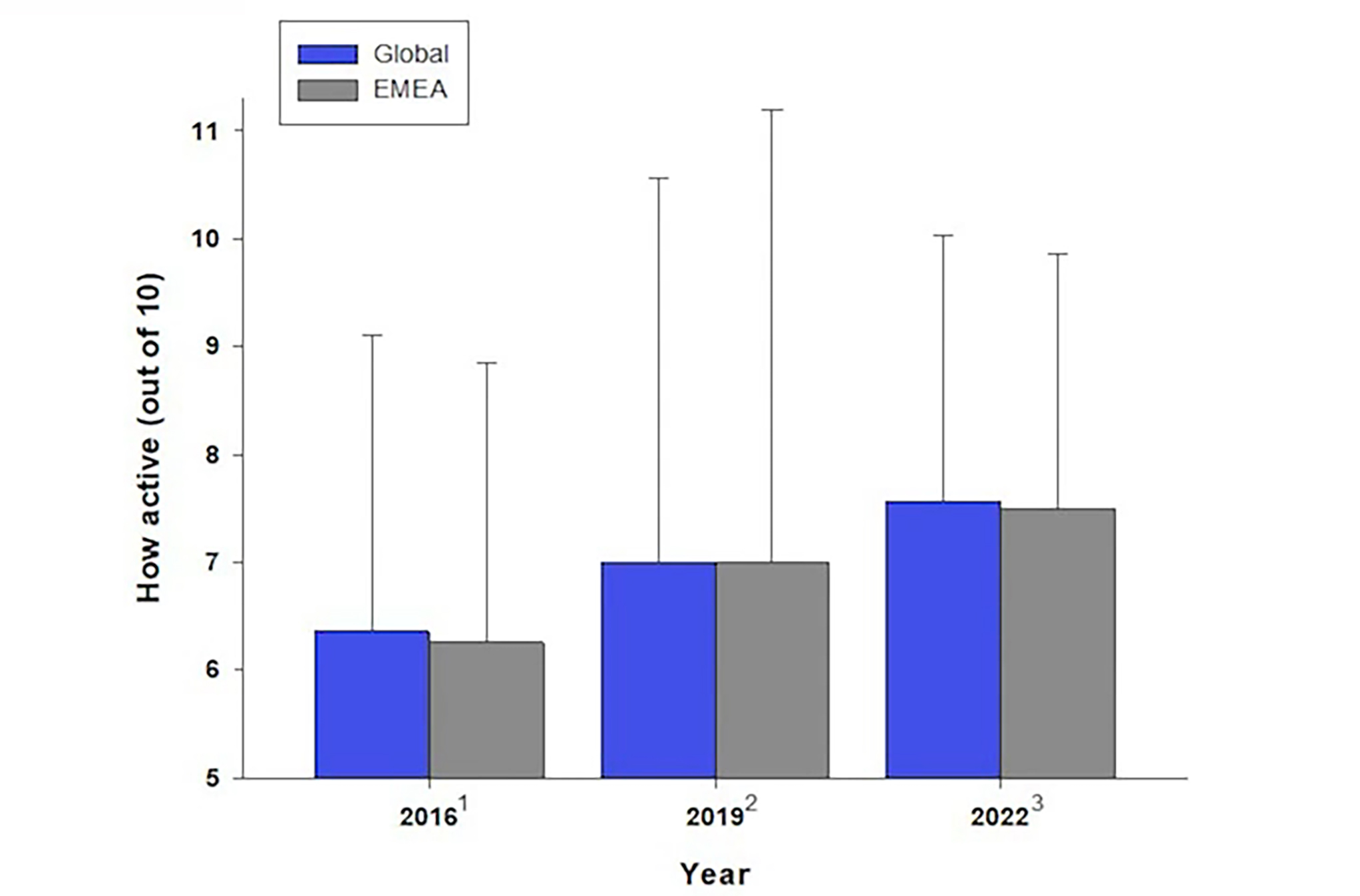

The global practitioner survey has looked at the clinical practice of myopia management among 2,564 ECPs across the globe (figure 8). Now with three sets of data, Wolffsohn has been able to look at trends in ECP behaviour regarding myopia management.8 Figure 9 shows how concern about the increasing prevalence of myopia is growing among ECPs involved in paediatric practice. Not surprisingly, this is leading to an increase in myopia management activity (figure 10).

Figure 8: Global ECP participation in the global practitioner survey on the uptake of myopia management

Figure 9: Increasing concern about myopia prevalence among ECPs both globally and in Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA)

Figure 10: Increasing ECP activity in myopia management from 2016 to 2022

Management Approaches

There then followed a review of management strategies as currently used across the world and nicely summarised in the slide shown in figure 11, based on the work of Jonas et al.9

Figure 11: Summary of management strategies for myopic progression9

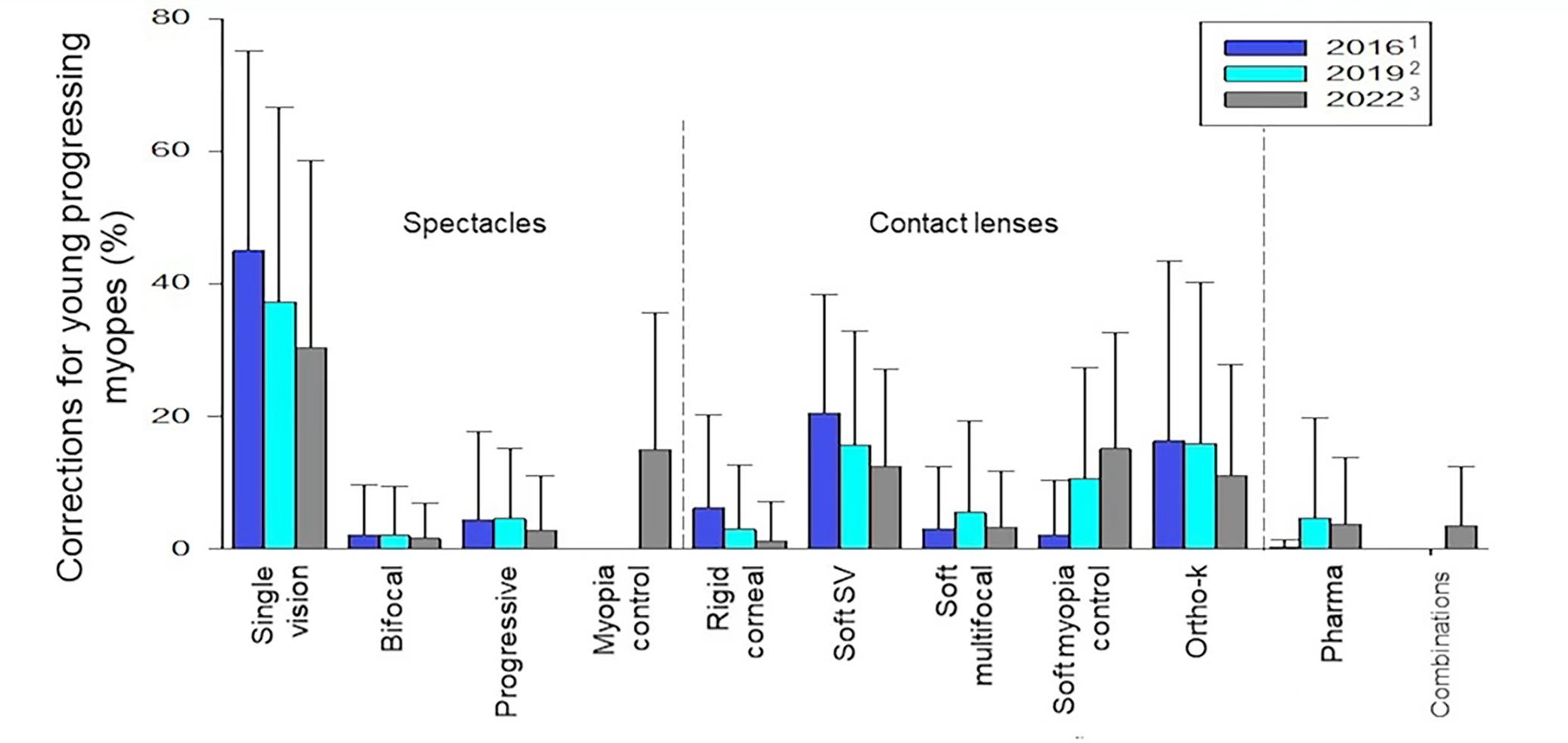

The IMI is a global concern, and it was emphasised that the approach to myopia management is likely to be influenced or constrained by local legal requirements, guidelines and ethical considerations. That said, Wolffsohn was able to summarise the approaches used in management and how they are changing over the past few years, with a focus now on Europe and the Middle East and Africa, or EMEA (figure 12).

Figure 12: Approaches to myopia management in EMEA in 2016, 2019 and 2022

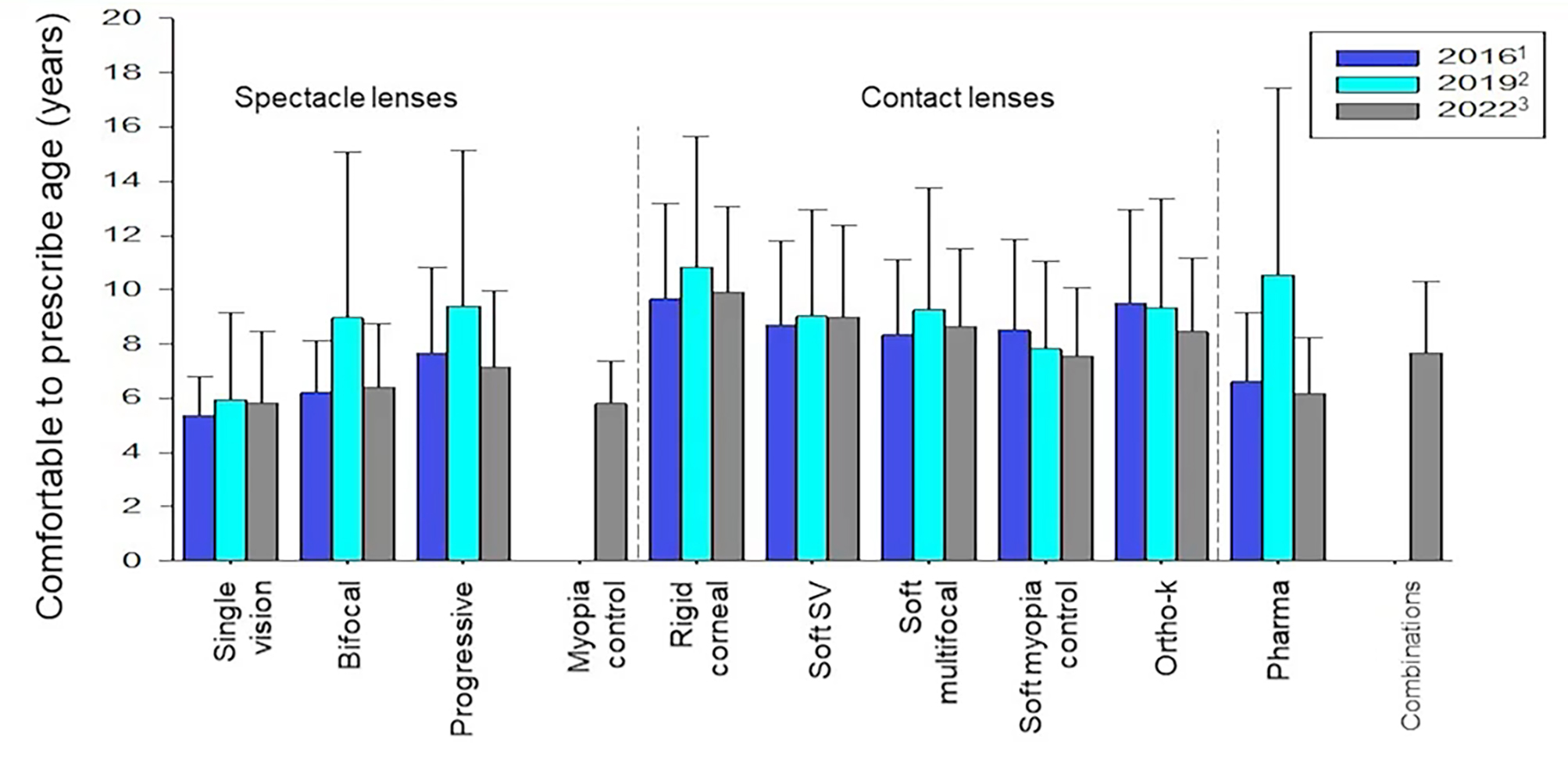

Another point of interest the analysis has revealed is that the age at which ECPs first intervene with any form of myopic management is reducing, being roughly six years for spectacles and pharmaceutical correction, and eight years for contact lenses (figure 13). When it comes to the minimum level of myopia at which an ECP might first intervene with myopia management, the UK and Ireland are leading the way with over 60% starting at -0.50DS, as opposed to under 40% doing so in the US.

Figure 13: Age of first intervention according to technique in 2016, 2019 and 2022

When asked about barriers to myopia intervention, regional variation is again seen. However, the cost to the patient is a significant barrier across the board.

The Future

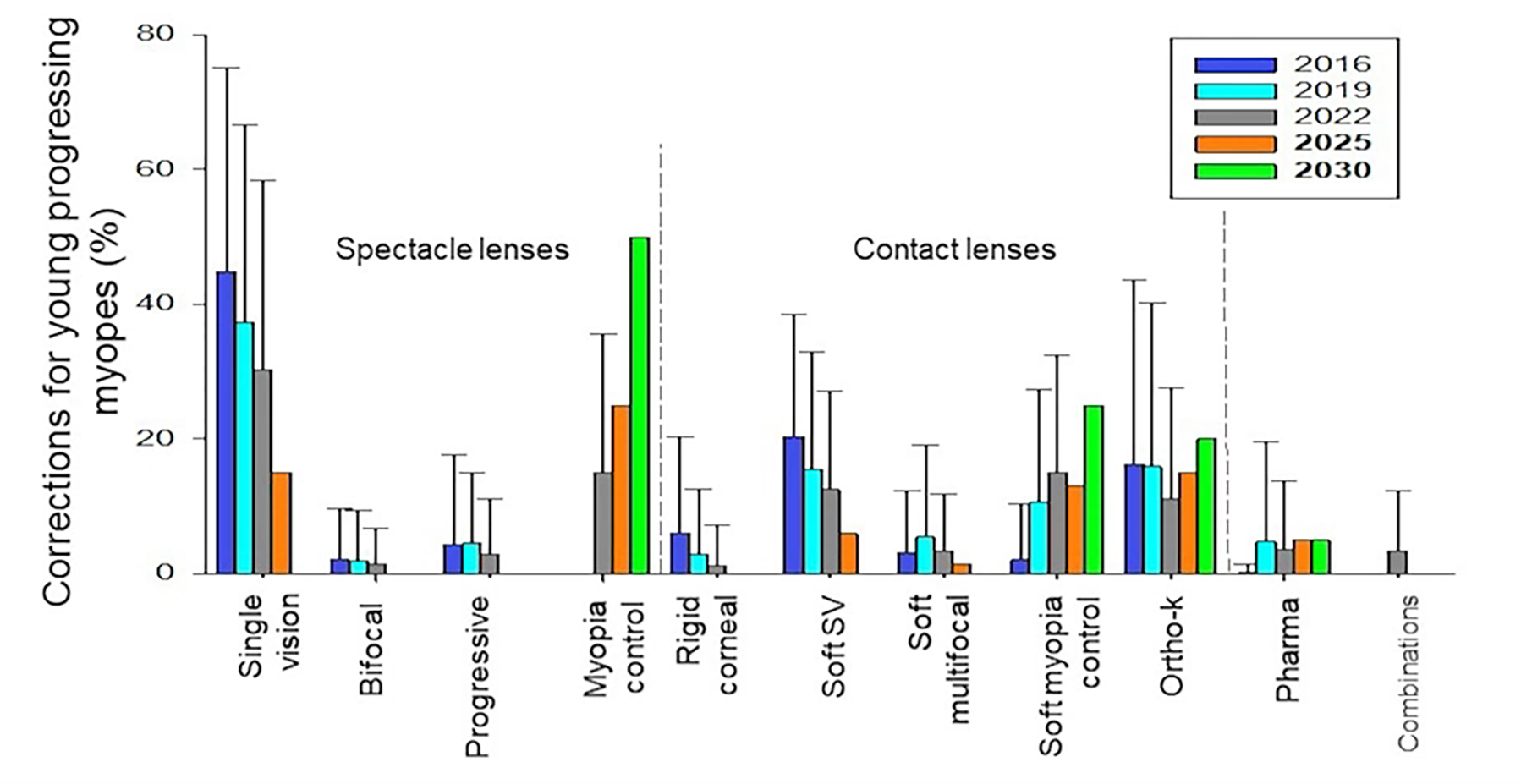

The most startling data was presented when Professor Wolffsohn was asked to predict how young progressive myopes are likely to be managed in the coming years. Based upon the trends already analysed, it can be extrapolated that, by the year 2030, there will be a complete move to dedicated myopia control designs of spectacle lenses and contact lenses (figure 14) and an end to single vision correction for this growing group of patients.

Figure 14: Predicted correction options used for correcting progressive myopic children. Note the complete move away from traditional spectacles and contact lenses by 2030

Final Thoughts

During a lively Q&A session, one particularly pertinent question focused on whether the uptake of myopia management has been slower in those areas where the increasing prevalence has been less of a concern; in other words, here. All agreed that, while this has certainly been the case in the past, there is no longer any scope for complacency and myopia management is here to stay; including throughout UK practices.

References

- Flitcroft DL. Is myopia a failure of homeostasis? Experimental Eye Research, 2013, 114, pp16-24

- Lin LL et al. Prevalence of myopia in Taiwanese schoolchildren; 1983 to 2000. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 2004, 33(1), pp27-33

- Jung S-K et al. Prevalence of myopia and its association with body stature and educational level in 19 year old male conscripts in Seoul, South Korea. Investigative Ophthalmology & Vision Science, 2012, 53(9), pp5579-5583

- Tideman JW et al. Association of axial length with risk of uncorrectable visual impairment for Europeans with myopia. JAMA Ophthalmology, 2016, 34, pp1355-1363

- Bullimore MA et al. The risks and benefits of myopia control. Ophthalmology, 2021, 128(11), pp1561-1579

- IMI White Papers & Clinical Summaries; volumes 1 and 2. Downloadable at: https://myopiainstitute.org/imi-white-papers

- IMI Facts and Findings Infographic. Downloadable at: https://myopiainstitute.org/resources

- Wolffsohn J et al. Global trends in myopia management attitudes and strategies in clinical practice. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 2016, 39(2), pp106-116

- Jonas JB et al. Prevention of myopia and its progression. IOVS, 2021, 62(5), p6