Eye care practitioners (ECPs) see patients on a regular basis so are ideally placed to detect conditions other than just those specific to the eye that might otherwise not be directly reported. They can then ensure that patients understand that help is available and how this might be sought. Hearing loss occurs for many reasons, is often age-related and in many cases linked with sight loss.

Furthermore, loss is often insidious in onset and may be causing problems for individuals and the people around them in a way that they might not easily pinpoint. ECPs should be aware of the nature of hearing loss, be able to identify patients where there may be a concern, and know the best advice to help the patient address the deficit. It is also essential to be able to communicate effectively with patients who have hearing loss in order to provide adequate eye care. It is also important to be aware of the wealth of support services offered by various allied healthcare professionals and charities.

This article is an overview of hearing loss and aims to offer the essentials that should be useful to all categories of registered eye care practitioner and their support staff.

The Extent of the Problem

Here are a few current facts compiled by the UK charity Royal National Institute for Deaf People, previously known as Action on Hearing Loss from 2011 to 2020 (rnid.org.uk).

- In the UK there are 12 million adults with hearing loss greater than 25 dBHL. This is equivalent to one in five adults.

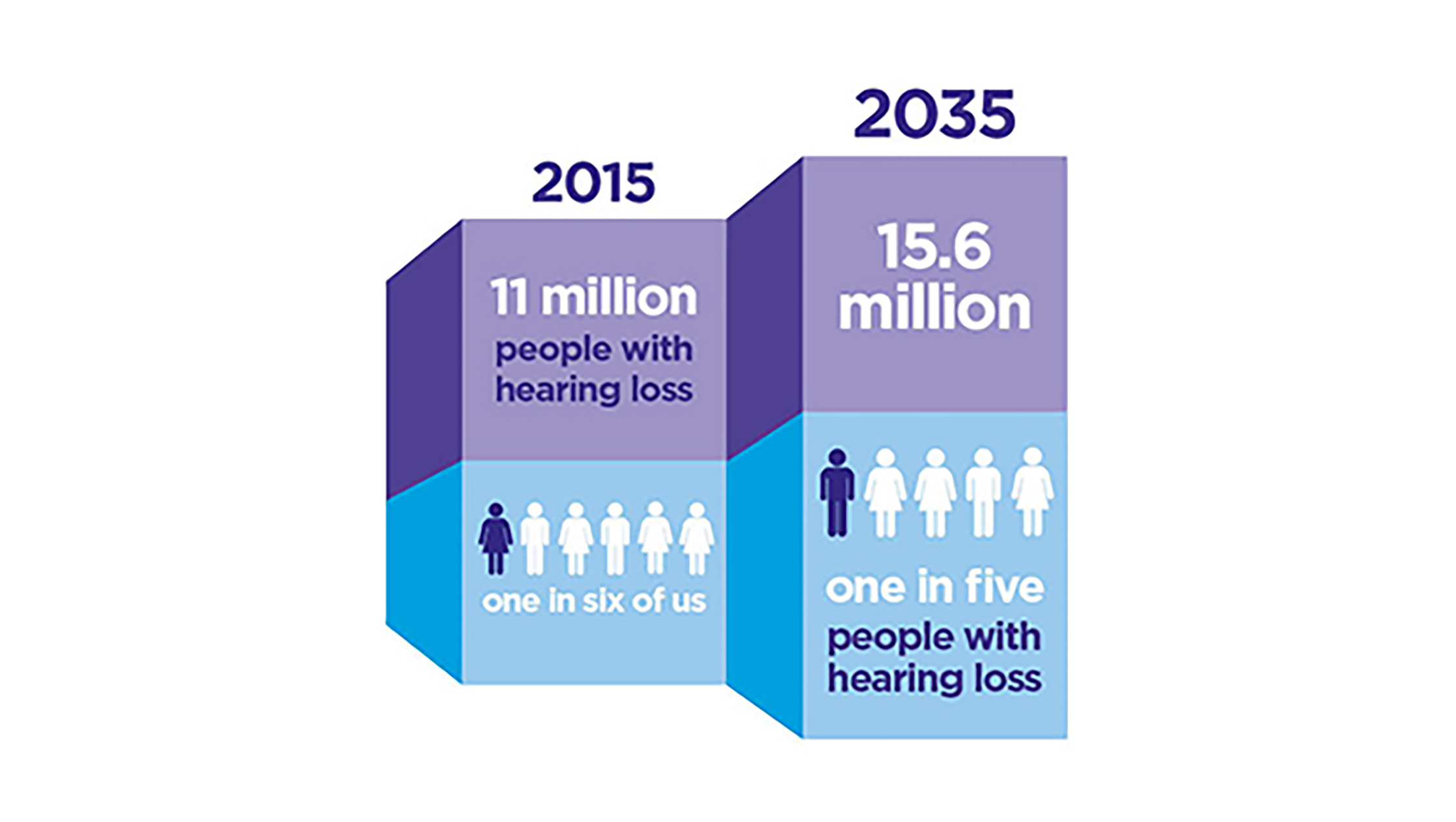

- By 2035, it is estimated that there will be 15.6 million people with hearing loss in the UK, an increase of nearly five million in 20 years (figure 1).

- Hearing loss is becoming more prevalent, not just related to increased life expectancy, but part linked with the noisy modern world.

- More than 900,000 people in the UK are severely or profoundly deaf.

- There are more than 45,000 deaf children in the UK, plus many more who experience temporary hearing loss.

- More than 70% of over 70-year-olds and 40% of over 50-year-olds have some kind of hearing loss.

- 24,000 people across the UK use sign language as their main language, although this is likely to be an underestimate.

- There are approximately 250,000 people in the UK with both hearing loss and sight loss. Of these 220,000 are aged 70 or over.

- Around 6.7 million people could benefit from hearing aids.

- On average, it takes 10 years for people to address their hearing loss.

- Around one in every 10 UK adults has tinnitus. This increases to 25 to 30% of over 70-year-olds.

- 45% people who report hearing problems to their GP are not referred for a hearing test or hearing aids.

Figure 1: Prevalence of hearing loss in the UK

Normal Hearing

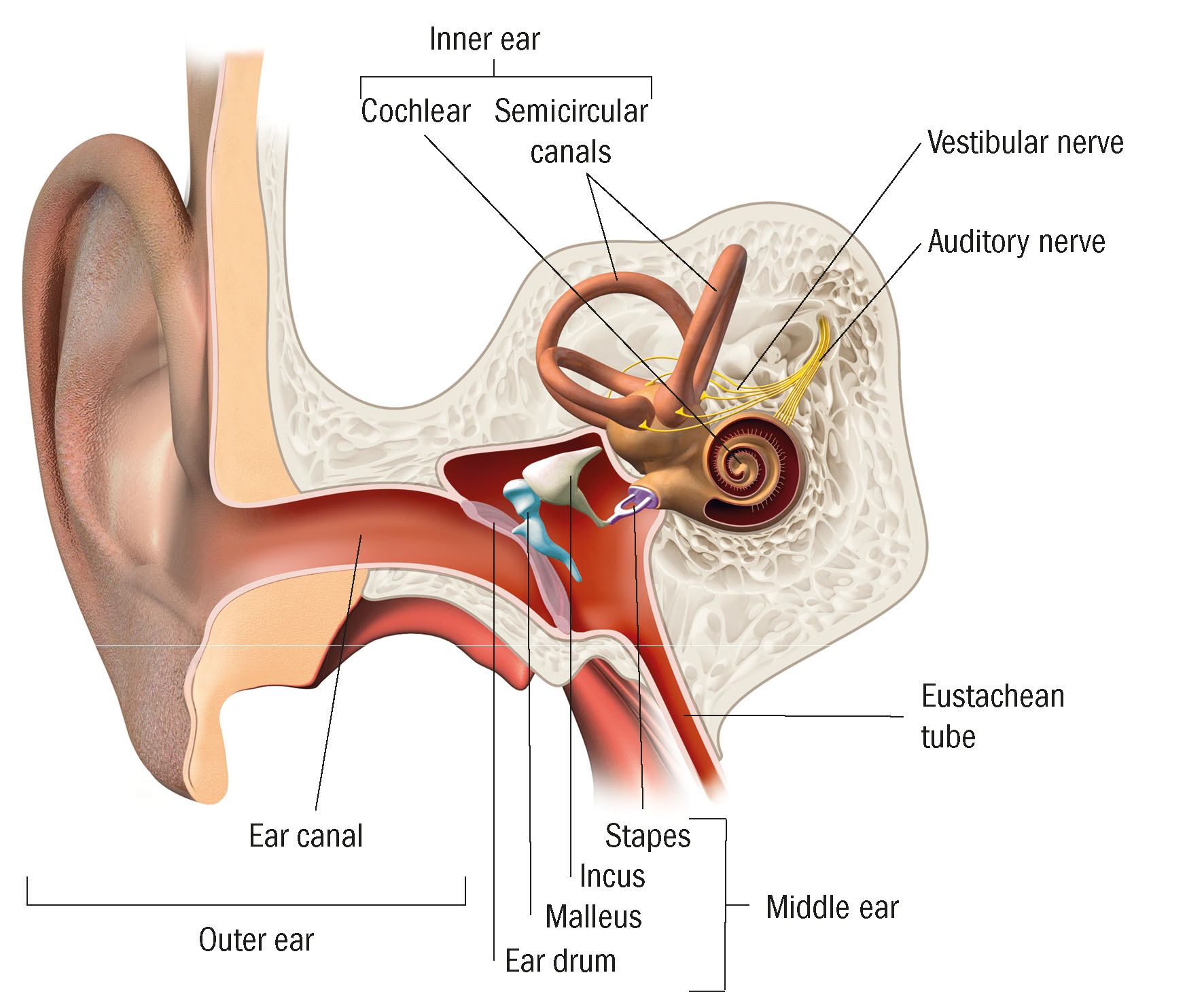

Having two ears helps humans in the localisation of sound and, indeed, has links with the visual system to help develop an accurate overall percept. Each comprises of an outer ear, or pinna, middle ear and inner ear (figure 2).

Sound is a compression wave, requiring a medium for transmission (‘in space no one can hear you scream’). The frequency of the compressions in the medium dictates the pitch of the sound and the human ear of a young person can detect frequencies from 20Hz to 20,000Hz. The difference in pressure between the compression and the gap in between is the amplitude and this dictates the volume or loudness. Loudness is measured in decibels (a logarithmic expression of the amplitude ratio). Normal speech is around 65dB and noise of 120dB or more may cause pain or damage to the ear. Loudness is further influenced by the frequency, with humans having a peak sensitivity to frequencies of 3,000Hz.

Figure 2: Gross anatomy of the ear

The pinna is designed to capture sound waves (analogous with, say, a satellite dish for radio waves) and funnel them into the ear canal (or external auditory meatus) within which the sound resonates and causes the eardrum (or tympanic membrane), which separates the outer and middle ear to vibrate in a way dictated by the nature of the pressure wave (analogous to the membrane on a loudspeaker).

The middle ear contains three linked bones or ossicles, which link the eardrum to the oval window at the start of the inner ear. These bones, the malleus, incus and stapes, are, as every pub quizzer knows, the smallest bones in the body and amplify the incident pressure wave. Two muscles, the tensor tympanum and the stapedius, attach to the bones and dampen any extreme bone vibration. Air is directly available to the middle ear via the Eustachian tube from the pharynx so ambient air pressure either side of the eardrum is maintained in equilibrium. Sudden pressure changes, as for example experienced during a flight, is noticed as ‘ear popping’ during the equalisation process. The oval window is 20 times smaller than the eardrum and this greatly increases the intensity of the pressure waves reaching the inner ear.

The inner ear is essentially a system of fluid filled tubes forming two distinct structures:

- Cochlea; a snail-like whorled structure that converts the pressure waves into electric signals then transmitted to the brain.

- Vestibular apparatus; three semi-circular tubes filled with fluid and orientated to represent the three spatial dimensions. Fluid movements relative to the heads position and this movement is converted into electrical signals representing the head’s position in space.

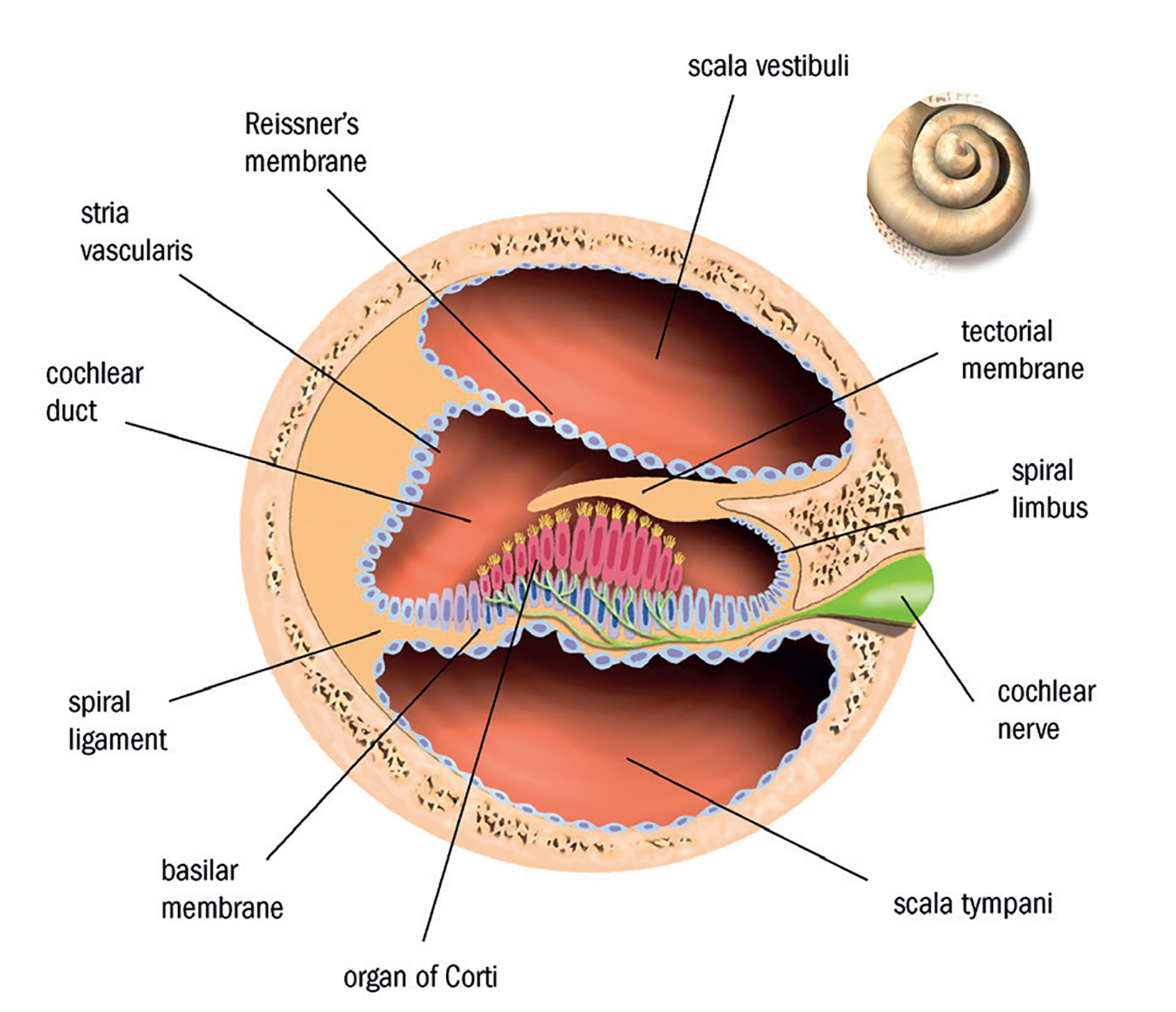

Figure 3 shows a cross-section of the cochlea and it is seen to have three chambers. The upper chamber, the scala vestibule, is directly linked to the oval window and the fluid within transmits the incident pressure wave along the cochlea, which then returns back along the lower chamber, the scala tympani, to be dispersed via a second, round window. Pressure waves are transmitted to the middle chamber, the cochlear duct, via the basilar membrane upon which lies the organ of Corti. This contains hair cells of ascending height along the cochlear length and these are able to resonate at individual frequencies dictated by their length. This is how individual frequencies stimulate specific neural signals to the brain, transmitted via the cochlear division of the 8th (vestibulocochlear or auditory) cranial nerve. The other division of the 8th nerve is linked to the vestibular apparatus.

Auditory signals pass through the brain via the lateral meniscus and inferior colliculi, then the medial geniculate nucleus to the primary auditory cortex (for sound recognition) located in the temporal lobe. The adjacent secondary auditory cortex is involved in sound localisation, language and music perception.

Understanding the anatomy helps explain the various causes of hearing loss.

Figure 3: Structure of the cochlea

Causes of Hearing Loss

Essentially there are two types of hearing loss:

- Conductive; usually localised to the outer and middle ear, a blockage or structural change prevents conduction of the compression wave adequately to the cochlea. Sound is reduced or muffled. Depending on the underlying cause, conductive hearing loss may be reversible.

- Sensorineural; damage to the cochlea or auditory neural pathway preventing adequate transmission of neural signals to the brain. Such loss is permanent.

Where both processes occur, the result is described as mixed hearing loss. Let us briefly describe some common causes of the above.

Conductive Loss

Ear wax

Secretions from the wall of the ear canal have an antiseptic role and help remove foreign particulate matter. Aggregations form a wax-like substance, of amounts related to individual’s skin type, and can block the canal and disrupt compression wave resonance. It is easily identified by an otoscope, and removed by loosening drops (olive oil is useful) or in stubborn cases, syringing. The latter is not possible where there has been damage to the eardrum (say, after a very loud noise insult) and specialist intervention is needed. Syringing needs to use sterile fluid of body temperature otherwise convection currents are set up in the vestibular apparatus causing dizziness and even nausea. This is exploited when a specialist wants to assess the health of the vestibular apparatus (the Caloric test).

Otitis externa

Inflammation of the outer ear caused by infections, skin disorders (such as eczema and psoriasis) or allergy. Swelling and discharge disrupt sound conduction. Treatment is specific to the cause.

Exostosis

Bony growths within the canal that may develop with repeated exposure to cold water. Surgery may be needed to restore uninterrupted conduction, but avoidance is the best policy (earplugs for swimming, for example).

Otitis media

This describes middle ear infections. These may spread from the nose or throat via the Eustachian communication. Most common in youngsters, infection may cause the eardrum to bulge causing severe earache and a dampening of sound because of restriction of movement of the ossicles. Treatment is specific to the underlying infection.

Otitis media is often followed by a build-up of fluid (often described as glue ear), which has not drained away via the Eustachian tube and so continues to muffle sound. Persistence for some months might require the surgical instillation of a drainage tube (or grommet) in the eardrum. Repeated otitis media may result in longer term fluid build-up (called chronic suppurative otitis media or CSOM) or a skin growth in the middle ear called a cholesteatoma. Surgery is typically needed to treat this.

Ossicle damage

Resulting from either congenital malformation or damage through injury or serious infection, this prevents normal bone transmission of sound signals. Surgical treatment includes the implantation of artificial replacements. Sometimes the ossicles, especially the stapes, suffer restricted movement or even become fixed because of abnormal bone growth (otosclerosis). This condition is most common in women aged 20 to 30 years and is exacerbated by pregnancy. Hearing aids may help, but a complete stapedectomy (the removal of complete or part of the original stapes bone and replacement with an artificial device) is sometimes required to restore adequate hearing.

Perforated eardrum

Trauma, sudden extreme pressure changes (such as from an explosion) and serious infections may perforate the drum and cause earache. This usually resolves in a month or two during which the ear must be protected from water and external fluid ingression.

Sensorineural loss

Applying a resonating tuning fork to the mastoid bone may allow a patient with no sensorineural loss to hear the sound even though conductive loss prevents them from hearing it when held close to the ear (Rinne’s test). If not, then sensorineural loss is likely. If the tuning fork is applied to the middle of the forehead, asymmetry in sound indicates either conductive loss in the poorer ear or sensorineural loss in the other. This may then be confirmed by covering the weaker ear and total loss of sound then confirms the latter (Weber’s test). The nature of the loss may be further investigated by seeing which frequencies the patient has lost sensitivity to. This process is described as audiometry and is the means by which an audiologist may prescribe an appropriate aid.

Presbycusis

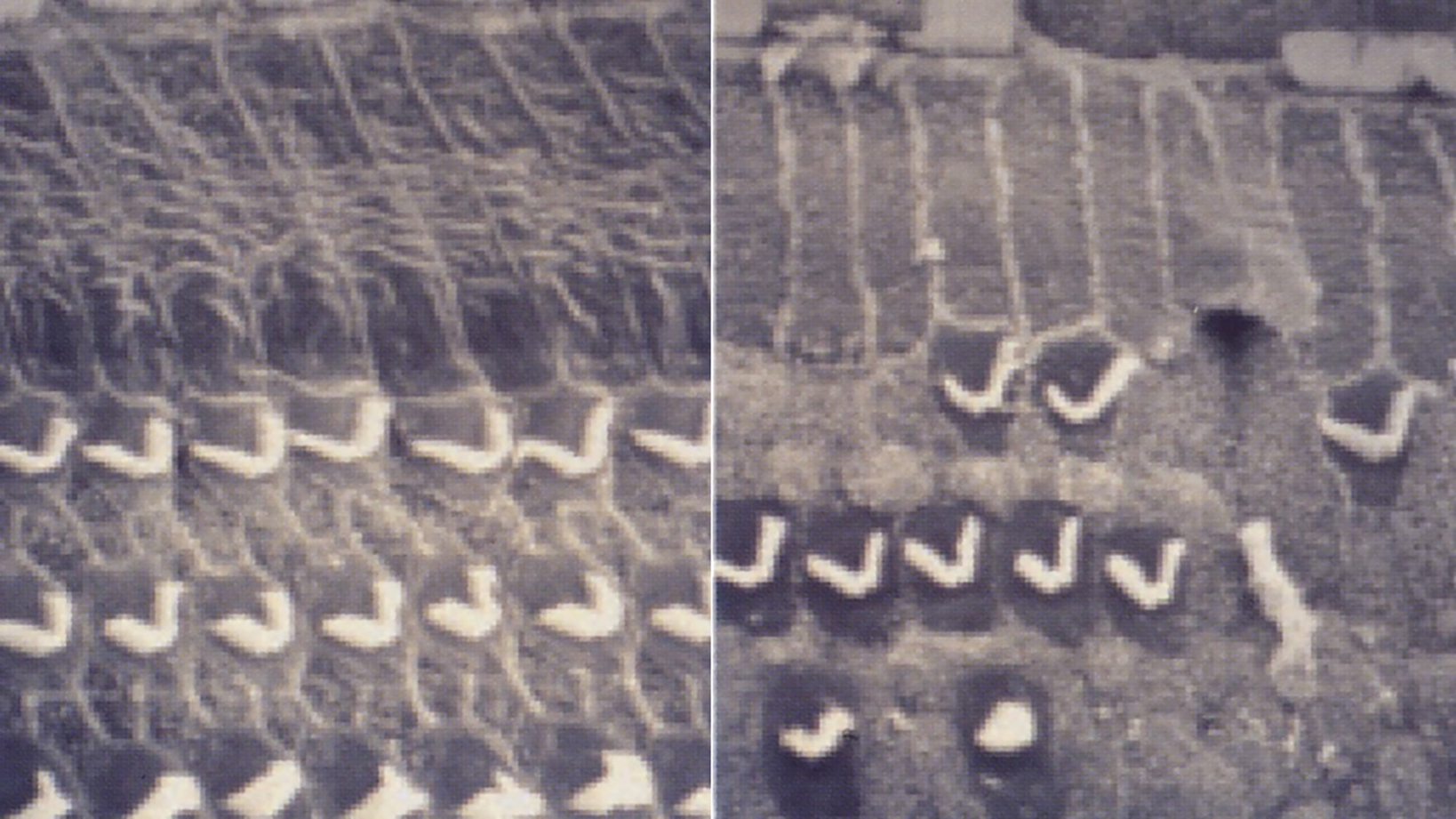

Just as presbyopia (‘presby’ or older and ‘opia’ sightedness) reduces our focusing ability as we age, similarly, ageing leads to a loss of high frequency responsive hair cells (figure 4) in the cochlea (presbycusis). Obviously, loud insult hastens this damage, hence restrictions on noise levels. Occasionally disease or damage or stimulus loss triggers spontaneous neural firing causing ‘ringing’ or tinnitus, a sort of aural Charles Bonnett. High frequency loss is particularly difficult as it means that we lose out on many of the consonants and higher pitched phonemes in the English language. This means that a person with a high frequency loss can experience sound coming through like it is a string of vowels and low-pitched sounds which is what makes it sound like someone is mumbling (figure 5). As a result, people living with this type of loss tend to blame other people for not speaking clearly and do not realise it is their hearing. It is also this loss with age that is widespread and of which we should all be aware when dealing with older patients.

Figure 4: Sensory loss; normal sensory tissue is shown on the left and damaged tissue on the right

People with sensorineural loss usually benefit greatly from hearing aids. Someone’s quality of life is likely to be greatly improved if this is made known to them. Severe cases of cochlear disruption may require a cochlear implant.

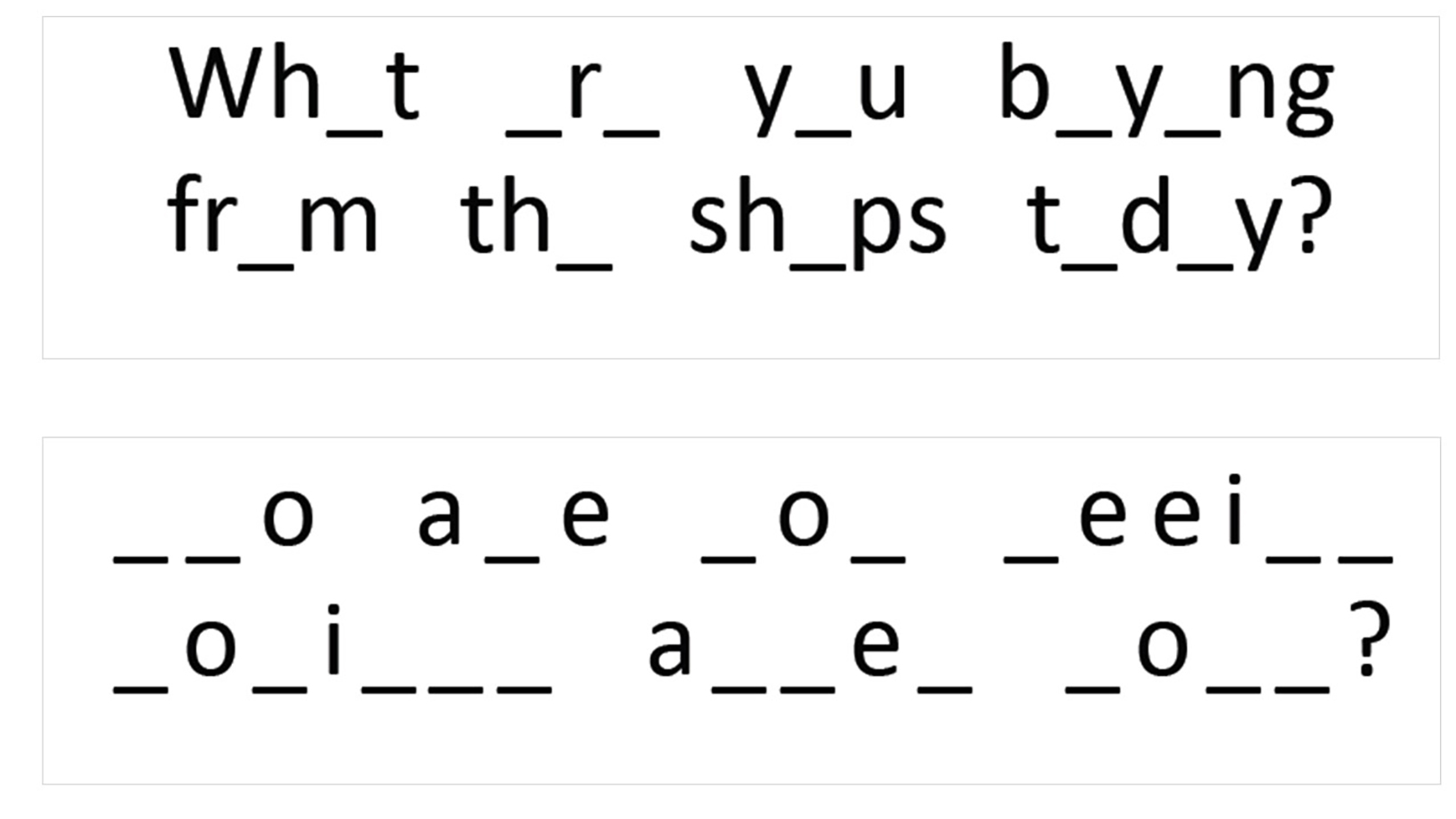

Figure 5: High frequency loss impacts upon consonants. The lower construct, where the consonants are missing, is much harder to interpret

Other important causes of sensorineural hearing loss worthy of note for the ECP include the following:

- Space occupying neoplasm impacting upon the auditory nerve; often somewhat erroneously called an acoustic neuroma, such a lesion is more correctly termed as a vestibular schwannoma as it results from excess Schwann cell growth on the vestibular nerve. It may cause hearing loss, tinnitus, balance issues and is sometimes a cause of headache that may prompt an eye examination. Though slow growing, symptoms may require surgery, which can result in loss of facial innervation and ocular exposure and lagophthalmos.

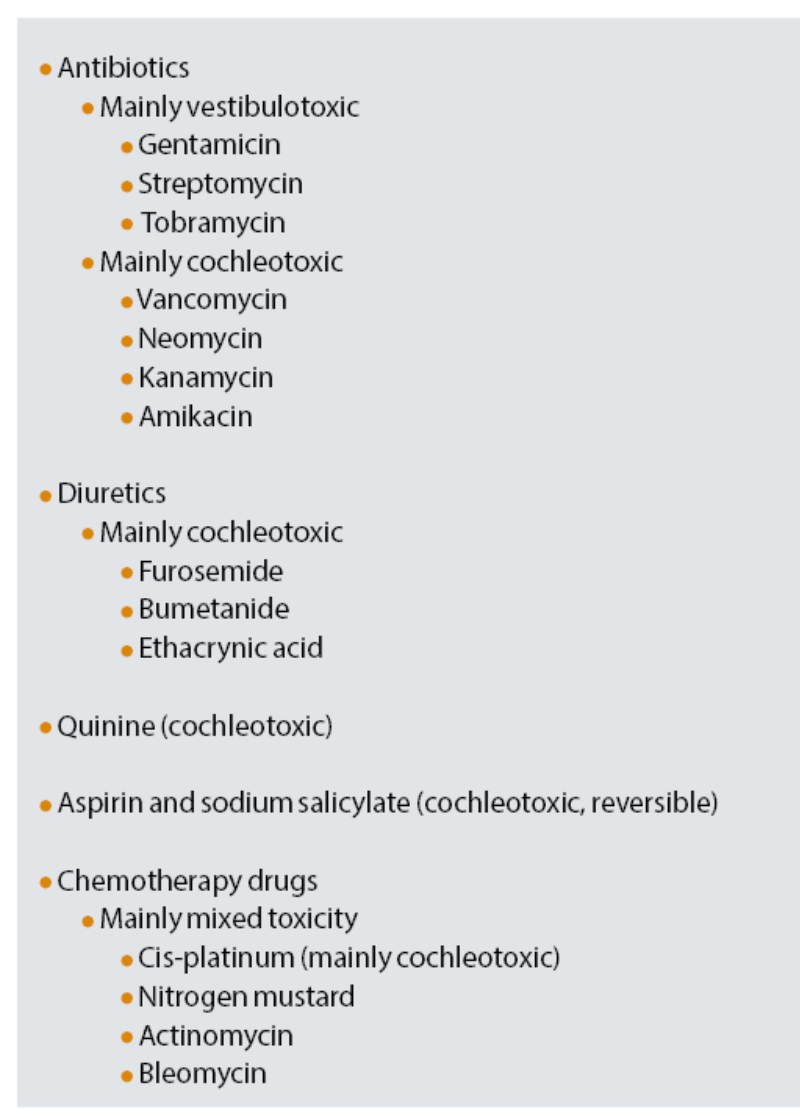

- Medication: table 1 lists some examples.

- Infectious diseases; these include mumps and meningitis.

- Meniere’s disease; this results from abnormal fluid levels within the inner ear structures causing hearing loss, tinnitus and balance problems.

- Inherited and congenital syndromes; about 30% of deafness in young children is associated with other medical conditions or syndromes. This type of hearing loss is usually called syndromic deafness. Of particular interest to ECPs is Usher syndrome, where the patient has deafness from birth and loses their sight gradually. Usher syndrome is the commonest cause of deaf-blindness and is usually signalled by the patient using a striped white cane to signal their hearing loss concomitant with sight loss. Interestingly, some patients with Duane’s retraction syndrome have other problems, such as hearing impairment, Goldenhar syndrome, spinal and vertebral abnormalities. Referral of Duane’s for sensory assessment is, therefore, recommended if not for the incomitancy.

- Birth complications; parturition may cause insult to the auditory pathway.

Table 1: Drugs linked with sensorineural hearing loss. Many anticonvulsants, antihypertensives and sedatives are ototoxic to some extent and may cause dizziness and vertigo

Types of help

It is important to remember that a wide range of assistance is available, and should be known about, to assist those with hearing impairment. Hearing loss may range from the profound, causing significant communication problems and major handicap, to the barely recognised, which may have subtle negative social impact. Congenital severe loss may result in developmental problems, particularly with regards to language skills, and so alternatives to standard verbal language might be helpful. Where loss is acquired, often enhancement of ability, such as through hearing aids and better communication skills adoption by correspondents, might be sufficient. Each case is different and this article can only offer an overview of different strategies.

From an ECP point of view, initial identification of the problem, adoption of good techniques, and awareness of where help might be sought to develop a tailored management approach is paramount. Our privileged position in seeing people, especially those at risk of sight loss such as the young and elderly, means we are also well-placed to check if ongoing strategies are appropriate and working well. How many readers, for example, have found they regularly advise an elderly patient about switching on their hearing aid more often?

For this overview, I have considered management in three main areas:

- Communication strategies

- Treatment strategies

- Support services

Communication Strategies

Patient considerations

It is always important to recognise that hearing impairment affects people in different ways. Acquired loss, particularly in the elderly, may even be considered a normal ageing change and highlighting it as otherwise may result in a negative or even aggressive response. Always accentuating the positive, by reminding people that help may make things easier, is usually the best approach.

It is rare for the ECP to be the first to identify a severe hearing loss. The opposite is true for less severe acquired loss and typical indicative behaviours to look out for include:

- Calls for repetition

- Irrelevant or nonsensical answers

- Misinterpreted instructions

- Hand cupping around ears

- Leaning forward when listening

- Staring at practitioner’s lips during conversation

- Speaking loudly

Recognising such clues might not automatically lead to the question ‘how is your hearing?’ Indeed, some authorities suggest this is more often than not met with the answer ‘fine’. A better approach might be a more direct inquiry, such as ‘does your hearing loss cause you any problems?’

Congenital hearing loss may be profound and require specialist communication strategies. That said, it is worth remembering that deafness in children has a strong association with ocular and visual problems in both the young and the elderly and so one should never exclude assessment of the other.

Finally, as with sight loss, it is useful to be aware of the stigma associated with terminology such as ‘deaf’ and ‘deafness’. Even though these terms have an acceptance among the deaf community and are used by charitable organisations, it might not necessarily be the case that recently acquired loss as might be commonly met in eye care practice should be described as such and so doing risks alienating the patient and perhaps reducing the opportunity for encouraging the sufferer to seek help.

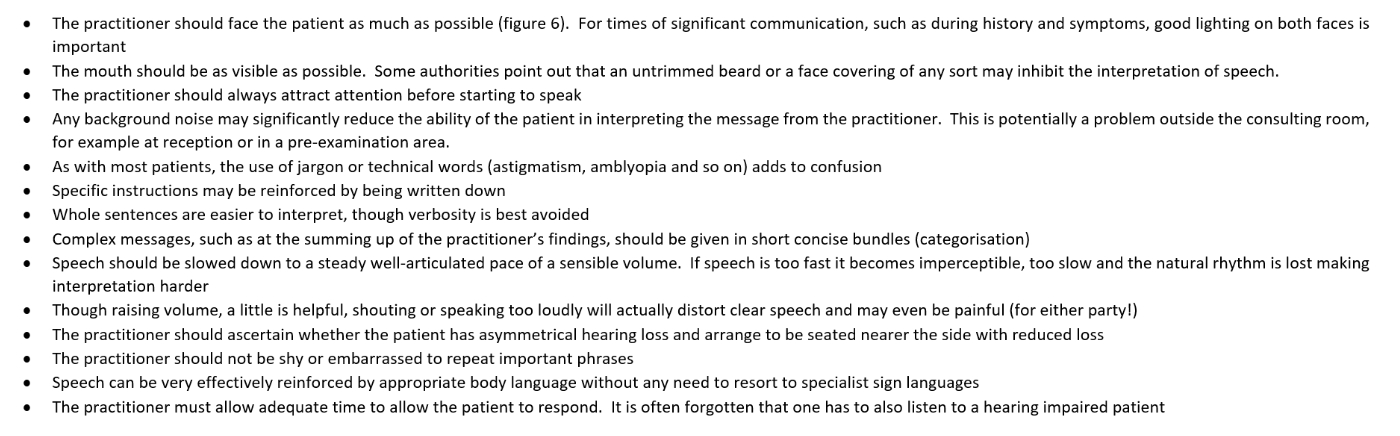

Figure 6: The ECP should face the patient as much as possible

ECP communication skills

When communicating with a patient with a hearing impairment in eye care practice, the general points outlined in table 2 should be considered:

Visual clues, traditionally written on paper, are often useful and the advent of tablets, both with electronic fonts and handwritten touch capability, are often very useful to support verbal technique (figure 7).

Figure 7: Tablets are very useful to support verbal technique

When working in the low vision environment, it is worth remembering that vision of at least 6/96 is required for useful lip reading and visual cues should be tailored to the expected vision capability of the patient.

Even low levels of acquired hearing loss may impact upon subjective assessment, for example seeming to impair recall when a patient is being asked to compare current and previous image quality. Tolerance is the key and a maintenance of awareness of the indicative behaviours mentioned previously.

In general, improved listening and speaking (auditory-oral) techniques help maintain communication and, in children, may help with the development of some literacy skills. Often a combination of techniques is adopted and may include the following:

- Cued speech; this uses hand shapes to represent the sounds of English visually. Technically it can be used to supplement other approaches, either auditory-oral or sign based, but its major function is to support the understanding of spoken English and the development of literacy. Hand shapes are ‘cued’ near to the mouth to make clear the sounds of English which, when lip read, look the same. It is based on the principle that cueing in this way will make every sound and word clear to deaf children and therefore enable them to have full access to spoken language.

- Lip reading; sometimes called speech-reading, this is the ability to read words from the lip patterns of the person speaking. It is hard to say how much speech can be understood just by relying on lip reading, as many speech sounds are not visible on the lips and lip patterns also vary from person to person, but it is estimated that only about 30% to 40% of speech sounds can be lip read even under the best conditions. Lip reading is never enough on its own and is used to support other communication approaches.

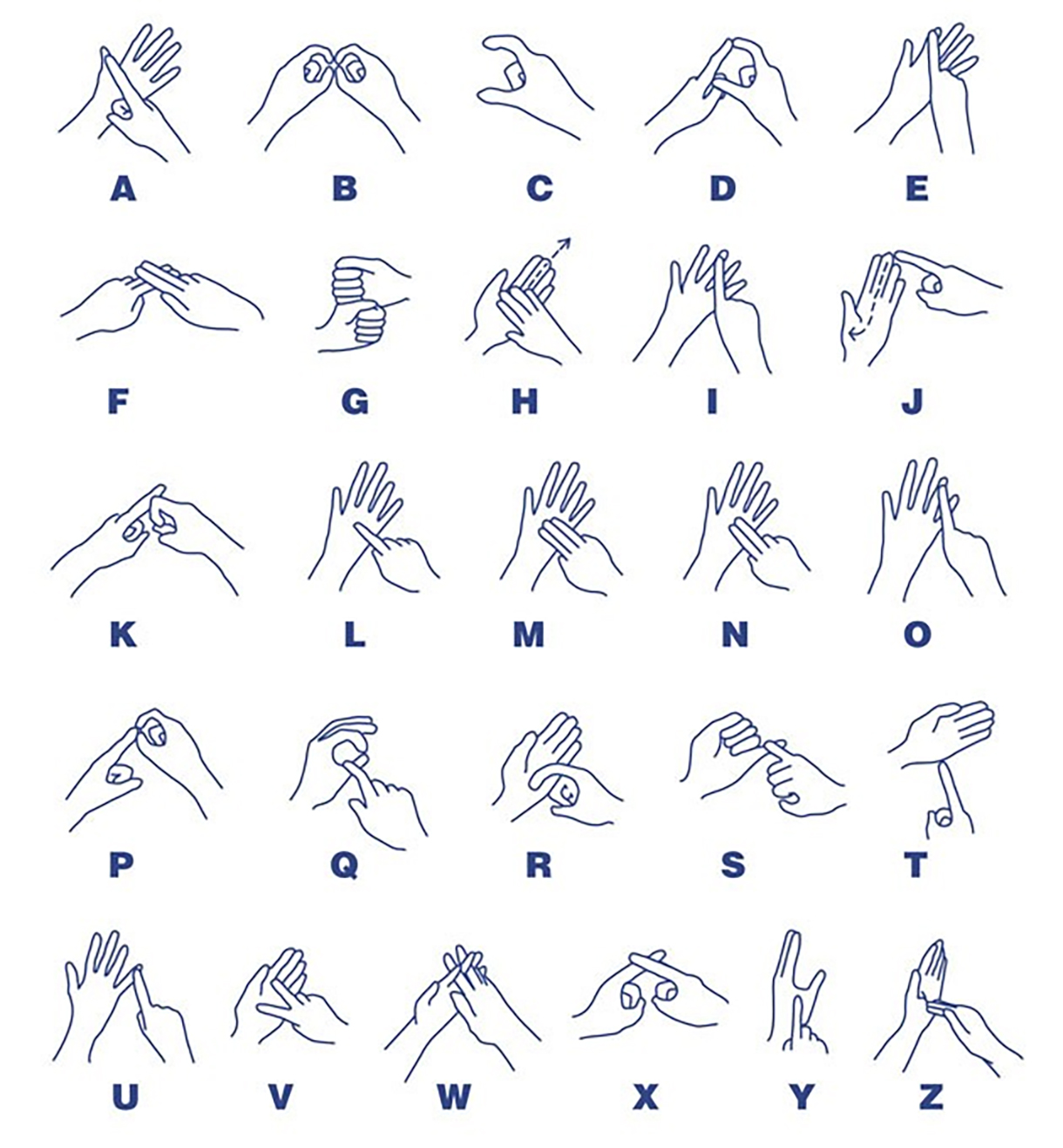

- Finger spelling; this uses the hands to spell out English words and letters. Each letter of the alphabet is indicated by using the fingers and palm of the hand. It is used to support sign language to spell names and places and for words that do not have an established BSL sign.

Specialist languages

Once considered very specialist, more and more clinicians in all areas of clinical practice are learning forms adapted forms of communication to help with interaction with those with hearing loss. The most widely used are as follows:

- British sign language (BSL). Although the United Kingdom and the United States share English as the predominant oral language (‘two countries divided by a common language’), British Sign Language (BSL) is quite distinct from American Sign Language (ASL) – having only 31% signs identical, or 44% with shared derivation. BSL is also distinct from Irish Sign Language, which is more closely related to French Sign Language (LSF) and ASL. It is also distinct from Signed English (see later).

BSL is a complete language with a unique vocabulary, construction and grammar. In the UK there are over 70,000 people whose first or preferred language is BSL. It is based upon the manual construction of individual letters (figure 8) combined with facial and other gestures to signify individual phrases, terms or concepts. It may be learned through a recognised certified education programme and is used both by those with hearing loss and those in charge of their care. People who use BSL may well bring a communication partner with them. It is important to maintain eye contact and talk directly to the person you are communicating with, not the interpreter. Also make sure that the person using sign language has an uninterrupted view of their communication partner. This will be especially important while giving directions and explanations during procedures such as ophthalmoscopy and retinoscopy when the lights are off and you effectively block their view.

Let Sign Shine is a campaign started by Norfolk teenager Jade Chapman to raise the awareness of BSL and attract signatures for a petition for it to be taught in schools. The campaign’s petition to the Parliament of the United Kingdom has attracted significant support.

- Signed English (SE) or Sign Supported English. There are a wide variety of signed languages, which do not have a distinct vocabulary, such as BSL, but instead follow the word order of spoken English with supportive signs or, in some case, contact patterns. Variety is wide and even might be self-designed by groups or pairings.

- Makaton. This is a language that uses signs, symbols and speech. It was developed by a speech and language therapist and two individuals from the Royal Association for Deaf People and is an acronym of their names. It is used by over 100,000 children and adults in the UK. The symbols used in the Kay Picture acuity test all have simple and widely used and understood Makaton signs.

Figure 8: British sign language (BSL) alphabet

Treatment Strategies

Management of conductive loss might be possible through a removal of whatever is preventing the normal conduction of sound. This might be:

- Wax removal; wax build up is common and a major cause of reversible conductive hearing loss. Though the obvious strategy is the removal of the wax, simply suggesting this to someone suspected of having this without careful otoscopic examination by someone trained to do so is not advisable. As the waxy build-up is often linked to skin secretion type, those with this form of hearing loss tend to have recurrence and so should know themselves when the time is right to either self-treat or seek help, usually via a practice nurse at the GP. Because a similar blockage may be due to or exacerbated by inflammation, a careful assessment prior to wax removal is usually advised. Softening of the wax, typically by twice daily use of an oily base such as olive oil, should give resolution within days. Cleaning with buds is not advised due to risk to the ear drum. Syringing (electric pumps are now used) with body temperature water is less used today for the same reason but might be required in particularly stubborn cases.

- Medications; if the underlying problem is a build-up of sound blocking matter from infection or inflammation, then medical treatment of the condition itself is required.

- Surgery; where conduction is caused by residual material or bone growth then surgical intervention may be required and possibly adapted to prevent future problems, as when a grommet is fitted.

For sensorineural loss, or persistent and difficult to treat cases of conductive loss, or indeed where the initial conduction problem has caused sensorineural loss, a hearing aid may be required.

Sensorineural loss, where permanent loss of hearing has been caused by damage to the cochlea or neural pathway for hearing, usually benefits from a hearing aid. These may be of several types.

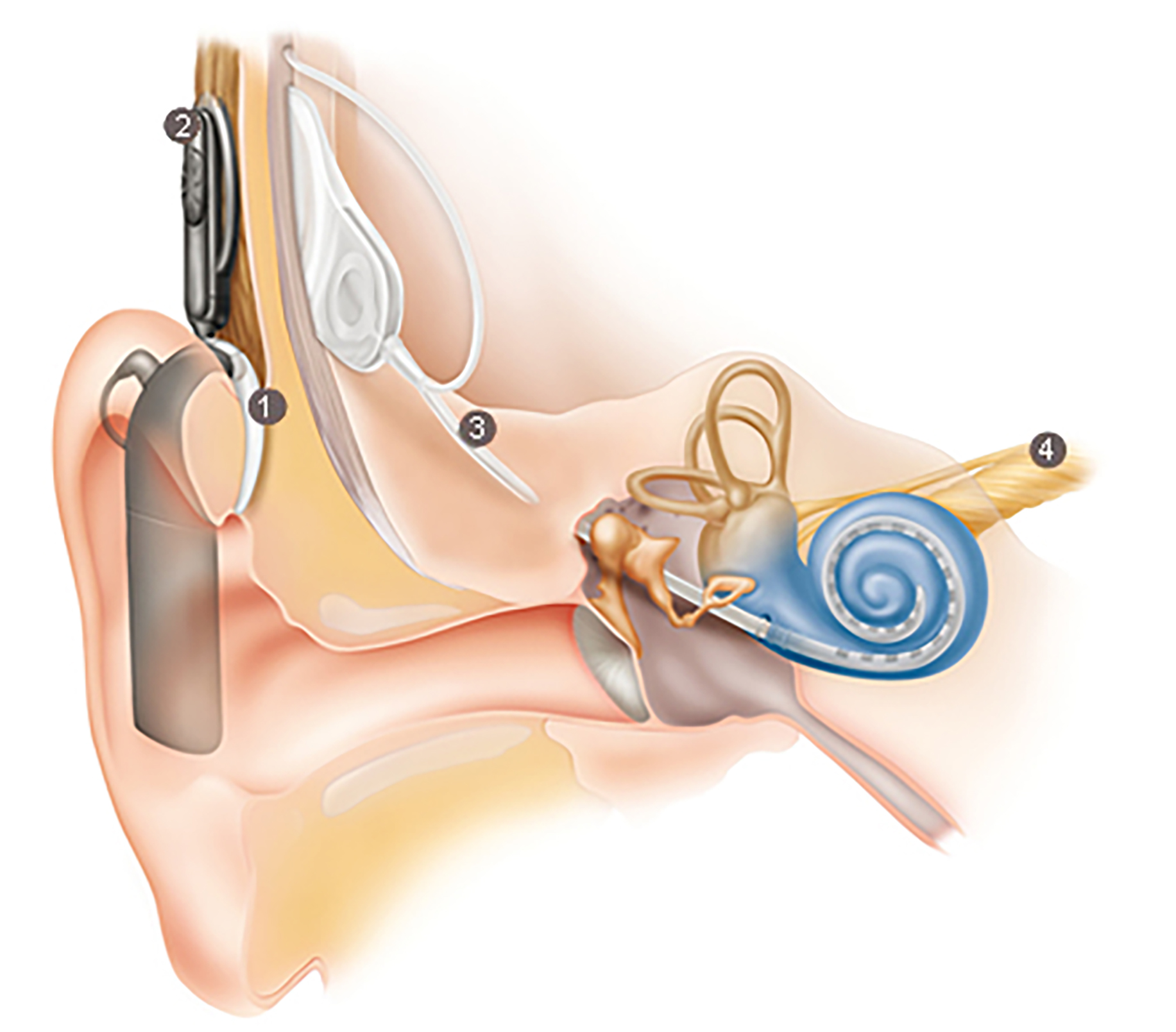

Cochlear implants

Though more likely considered a surgical intervention than a hearing aid as such, in severe cases of cochlear disruption, it is possible for an implant to be fitted that takes on some of the lost functionality of the cochlea. The implant comprises four elements (figure 9):

- A sound processor fitted behind the ear, which converts sound into digital code electrical signals, and contains the battery

- The sound processor transmits to coded signal into the implant within the skull

- The implant converts digital coded signal into electrical impulses that pass to an electrode placed within the patient’s cochlea

- The electrode stimulates the auditory nerve in place of the faulty cochlea

Figure 9: A cochlear implant (see text for key to numbers)

Hearing aids

Hearing aids may be analogue or, more likely, digital devices fitted in or around the ear that amplify sound. Analogue and digital hearing aids look very similar, but they process sound differently.

Analogue aids amplify electronic signals, while digital aids use a tiny microprocessor to process sound in a way that can be pre-programmed to match the profile dictated by the initial audiologist assessment, usually by a computer hook-up at during the assessment. Many digital aids can be programmed with different settings for different sound environments, for example a quiet living room or a crowded restaurant. Some even switch settings automatically to suit the environment. Digital hearing aids are designed to reduce background noise, which makes listening in noisy places more comfortable. They are also less likely to ‘whistle’, or give feedback.

Thanks to extensive lobbying by groups such as the RNID, some digital hearing aids are now available as standard on the NHS. Styles vary, though it is rare now to see aids incorporated into spectacle frames as once was the case.

Designs include the following:

- Behind the ear (BTE); for all ranges of loss and can be connected to assisted listening devices such as FM or Bluetooth. They include a tube fitted into the ear canal.

- Open and Receiver in Canal (Open/RIC); the ear mould is replaced with an open dome so most patients find them more comfortable as they do not occlude the ear. Also, lack of a tube means the sound is less likely to be distorted.

- In the ear (ITE or full shell); fitting into the concha or opening, they are sometimes required where more power is required for amplification than might be possible with in-ear devices.

- In the canal (ITC or half shell); filling only the bottom half of the external ear, they may be cosmetically more comfortable but offer less power than the ITE.

- Completely in the canal (CIC); these fit entirely inside the canal so are pretty much invisible, as portrayed on some recent TV adverts. Fitting requires skilled input by an audiologist and batteries and unit are at the more expensive end of the range.

- Invisible in the canal (IIC); the most recent addition to the hearing aid range, this is based on an impression of the deeper recesses of the canal so is cosmetically superior but requires skilled fitting and has a price to match.

Most of the concerns regarding cosmesis with hearing aids have now been addressed. There is even a website called ‘pimp my hearing aid’ with tips on doing just that.

Support Services

Most hearing loss first suspected in a patient by an ECP is best assessed by the GP practice. They can check for any treatable causes, such as a build-up of ear wax, or more concerning disease process requiring attention.

When these have been ruled out or treated, the remaining hearing loss (most likely presbyacutic) requires the assessment by an audiologist who will assess the loss and decide upon possible hearing aids. You can either be referred to an NHS audiology service for these hearing tests, or go to a private hearing care provider. Any hearing aids will be free from the NHS, but private, more advanced, options are paid for.

To find out what hearing services are available in any UK area, including access to an audiologist assessment, a good start is to go to www.nhs.uk/Service-Search/Hearing-impairment/LocationSearch/1799.

Under a scheme called Any Qualified Provider (AQP), some private hearing care providers also deliver NHS adult-audiology services. This means that if the scheme is available in a patient’s area and they meet the criteria, they will have more choice about which NHS audiology service they are referred to.

The RNID website allows you to search for audiology services in your area (private and NHS), and see ratings and comments made by people who have previously visited them; go to rnid.org.uk/information-and-support/local-support-services.

Just as with sight loss, there is a whole range of non-optical and electronic aids and gadgets, professional help and financial and social support available to those both registered and non-registered, hearing loss has a wide range of support services available. Registration as deaf or hard of hearing is possible, either via GP referral or self-referral to a hearing specialist, after an audiogram shows evidence of hearing loss causing impact beyond the levels required for continued living standards. Registration may offer access to a number of benefits (table 3).

Table 3: Some benefits that may available for those registered as disabled through hearing loss

The Access to Work scheme may allow hearing impaired people in employment support as the scheme requires an employer to support with help to enable them to continue working

A hearing-impaired child in full-time education may be assessed for a special educational need (SEN), of which hearing loss (as is sight loss) is on. By so doing, the child may gain support through specialist teaching staff and hearing aids.

Equipment

There is a wide array of aids, from amplified telephones and mobiles, conversation amplifiers, aided assistance for television viewing, flashing doorbells and text phones. These may be accessed through private suppliers or via groups like the RNID.

Many digital hearing aids may be set (usually to a ‘T’ setting) such that they detect signals from a loop microphone, which may be placed near to the person requiring attention. This may be a loop next to a clinician, bank worker and so on (a counter loop) or in a more public setting with the aim of amplifying sound and minimising background noise (a room loop).

As with low vision aids, the evolution of digital devices is leading to a rapid expansion of the range of available hearing aids.

Conclusion

This author has long advocated that ECPs are well placed to ask patients whether they have had a cardiovascular health check and this is particularly useful for those patients (typically, middle aged men) who are at risk of diseases like hypertension but are notoriously poor attenders for general health checks.

In a similar way, ECPs are well placed to first detect hearing loss in patients, to let elderly patients know about presbycusis and to let them know that treatment options are available.