The second of in a quarterly series of online events, supported by Alcon, took place recently and looked at the topic of contact lens comfort. In the first of two reviews of this event, the focus is upon:

- Managing contact lens discomfort

- Improving the contact lens experience for the patient

- Innovations to aid comfort

The second review, to be published next week, will consider the latest thinking concerning the tear film and ocular surface and how this influences the ideal contact lens for comfortable wear.

Managing Contact Lens Discomfort

Contact lens discomfort (CLD) is a prevalent issue. Nearly half of all contact lens wearers experience some discomfort.1 Though the prevalence rates of CLD range from 31%2 to 57%,3 this figure shoots up to 88% when considering reports of any degree of discomfort.4 Discomfort is one of the leading reasons for contact lens discontinuation.5, 6 It is therefore vital that CLD is managed in practice, to help patients get the most out of their contact lens experience, and ultimately, to avoid drop out.

Sulley et al investigated first year retention rates of neophytes fitted with contact lenses.7 Looking at those who dropped out within the first year, 25% dropped out in the first month, 50% by month two and 75% by month six. The first two months then, appear to be crucial to monitor new wearers and address any problems early on. The majority of soft CL wearers do not consult their eye care professional (ECP) prior to drop out,8 so there is a need for us to be proactive and reach out to patients who may be struggling with their contact lenses. There is a need to manage CLD in a timely and effective manner.

The Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) set up a workshop, which started in January 2012, pulling in 79 experts from the field, to evaluate CLD.9 A sub-committee was specifically assigned to investigate the management and therapy of CLD.10 A previous survey found that 47% clinicians would refit patients a different contact lens as their first line therapy.11

The report suggests the need for a systematic approach to managing CLD. It is important to assess the individual to explore concurrent conditions that could contribute to CLD and address these first. Once these factors are accounted for, one can determine the cause/s of CLD and implement the required treatment strategy. Such a system ensures that the contact lens is in a ‘clinically acceptable ocular environment.’9

Assess Patient Status

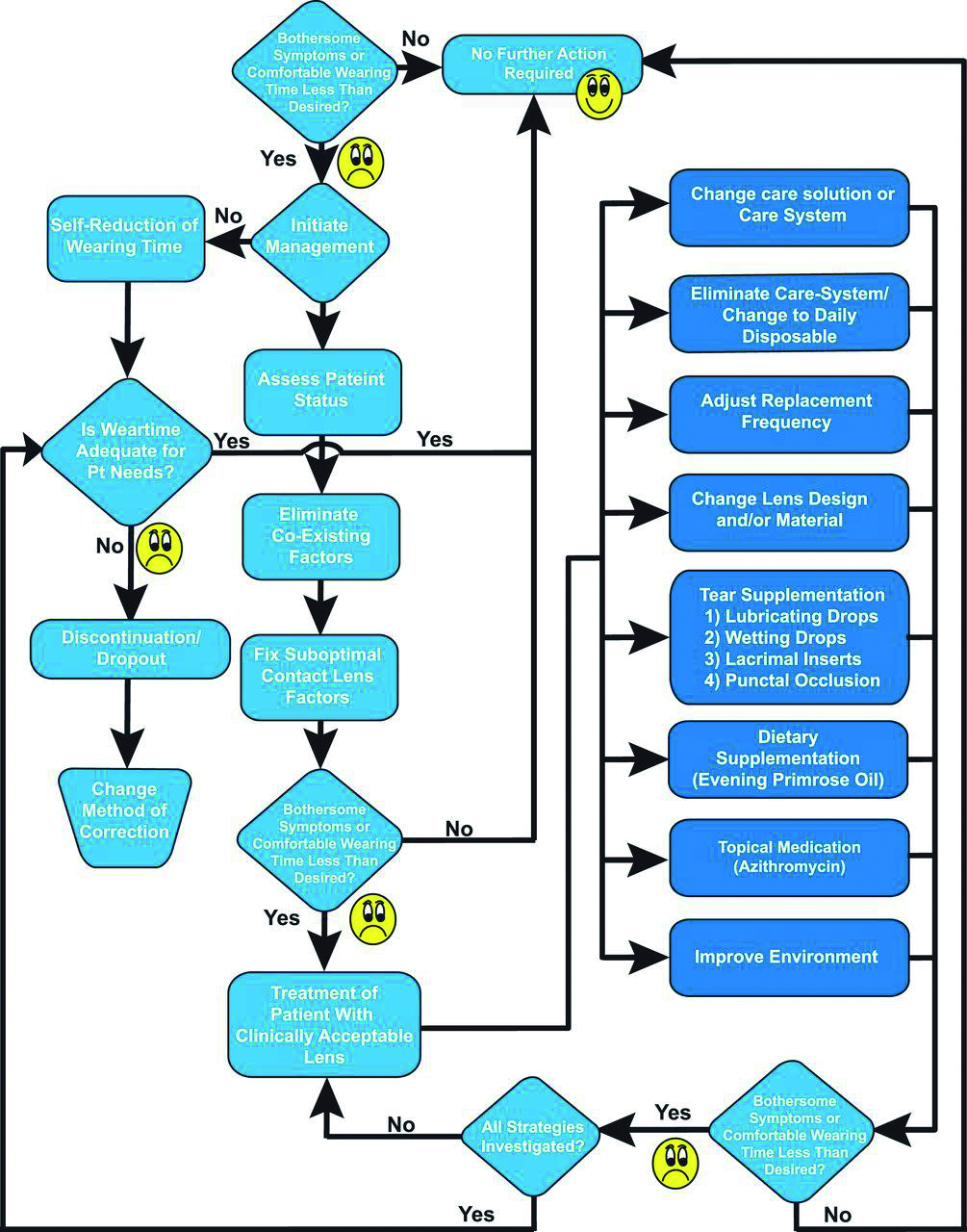

The TFOS International Workshop on CLD proposed a flowchart to use in deciding on the management pathway for each patient (figure 1). The first place in this flowchart tells us to ‘assess patient status’, in other words, to conduct a thorough history and symptoms to really establish all the details about the patient. In practice as ECPs, we are well-trained at taking a good history.

However, what points specifically need consideration and further elaboration to help identify and manage CLD? Table 1 is a summary of points to consider.

Table 1: Points to consider during history-taking

- Age and sex

- Symptom onset and duration

- Type of contact lens worn

- Care system and replacement schedule

- Use of additional wetting agents

- Wear time and pattern

- Adherence

- Occupational environment

- Coexisting disease

- Medications

Firstly, age and sex are two important factors, which give content to the complaint. It is well publicised that dry eye disease (DED) is more prevalent in females and with increasing age.12, 13 For CLD on the other hand, younger patients appear to be more likely to report problems than older patients.14-16

Then, there is the timing and symptom onset. Are they experiencing the typical end-of-day discomfort or are they getting the irritation as soon as they have the lenses in? Those two things will require different management strategies. The type of lens that they are wearing, so the material and the modality will again determine the eventual management. If the patient does need switching out of their current lenses, this information will help you decide the best alternative.

Figure 1: Flowchart proposed by TFOS10

The care system and replacement schedule are also important factors to note. Are the lenses monthly replacements or are they two-weekly lenses? What solutions are being used to clean and store the lenses in such cases, and is this adequate to get the deposits off? Deposit build-up on contact lenses can affect the lens wettability, and in turn, the comfort of the lenses.

Next, it is important to quiz the patient on lubricating drops. Are lubricating drops being used pre-insertion or during the course of contact lens wear? This would provide useful additional information. The wearing times and pattern of wear also helps to build a story. It not only provides baseline assessment, but if a management plan is implemented, it can be a great way to check if it is working by assessing if wearing time is increasing or back to the level that the patient would like.

It is also a vital piece of information between visits; if the wearing time is reducing between aftercares, we need to investigate this as ECPs to see if this is down to CLD or other modifiable factors. Sometimes, patients do not openly disclose problems, perhaps in fear that they may be told they can no longer wear contact lenses, and so we must look at non-verbal cues in practice.

Adherence is also an important factor to consider. The incorrect use of the lenses, the care system or the lens case can precipitate problems. It is also a good indicator if a patient is not cleaning their lenses properly, perhaps there is a deposit build up causing discomfort.

Adherence should be assessed at each visit; it is quite easy to assume that long-term wearers will be fully compliant, however, they may not have been taught the correct care regime or slipped into bad habits over time. It is important to delve into this area and educate patients because if no one has told them otherwise, they are going to continue with the incorrect practice.

Another consideration for the history taking is the occupational environment that the patient is exposed to. What is their life outside of this test room? Are they surrounded by air conditioning day to day? Are they in a humid environment, whether that is at work, at home or for a hobby? In the car, do they have their blowers on full blast?

These elements can also contribute to the comfort of the contact lenses as well as the stability of the tear film. Being fully informed on these factors is important in order to decide on the correct management plan.

Then, there is a need to establish the presence of any coexisting disease, both ocular and systemic. This will help to form thought processes to the management. Perhaps comorbidities are contributing to the symptoms. Also, from a management point of view, if something has been tried in the past and was unsuccessful, such details would help to avoid any repetitions.

Additionally, it is essential to take a thorough list of medications the patient is taking. That is, prescription and non-prescription, since pharmacology can affect the ocular surface. For example, patients may not declare taking multivitamins, however, these may contribute to DED.17

Coexisting Factors

Having completed a thorough history, the next step we need to look at is to eliminate coexisting factors. Since discomfort is a non-specific symptom, it is important to rule out any concurrent conditions that may be contributing to CLD and managing these first. At this point, looking at medicamentosa is helpful as discussed earlier.

For example, is the patient on preserved glaucoma eye drops? It is well documented that preservatives in eye drops can lead to ocular surface disease, and so perhaps in such an instance, switching to a preservative-free alternative may be beneficial.18, 19

Treating coexisting diseases such as such as Sjögren’s syndrome or rheumatoid arthritis is also important. Again, these can contribute to irritation, dryness and a poorer tear film, and so appropriate management of these is essential. Perhaps there is the presence of eyelid disease, such as MGD and blepharitis, which are quite common in practice. Treating these first is vital, as the insertion of a contact lens in such cases could just aggravate the ocular surface further.

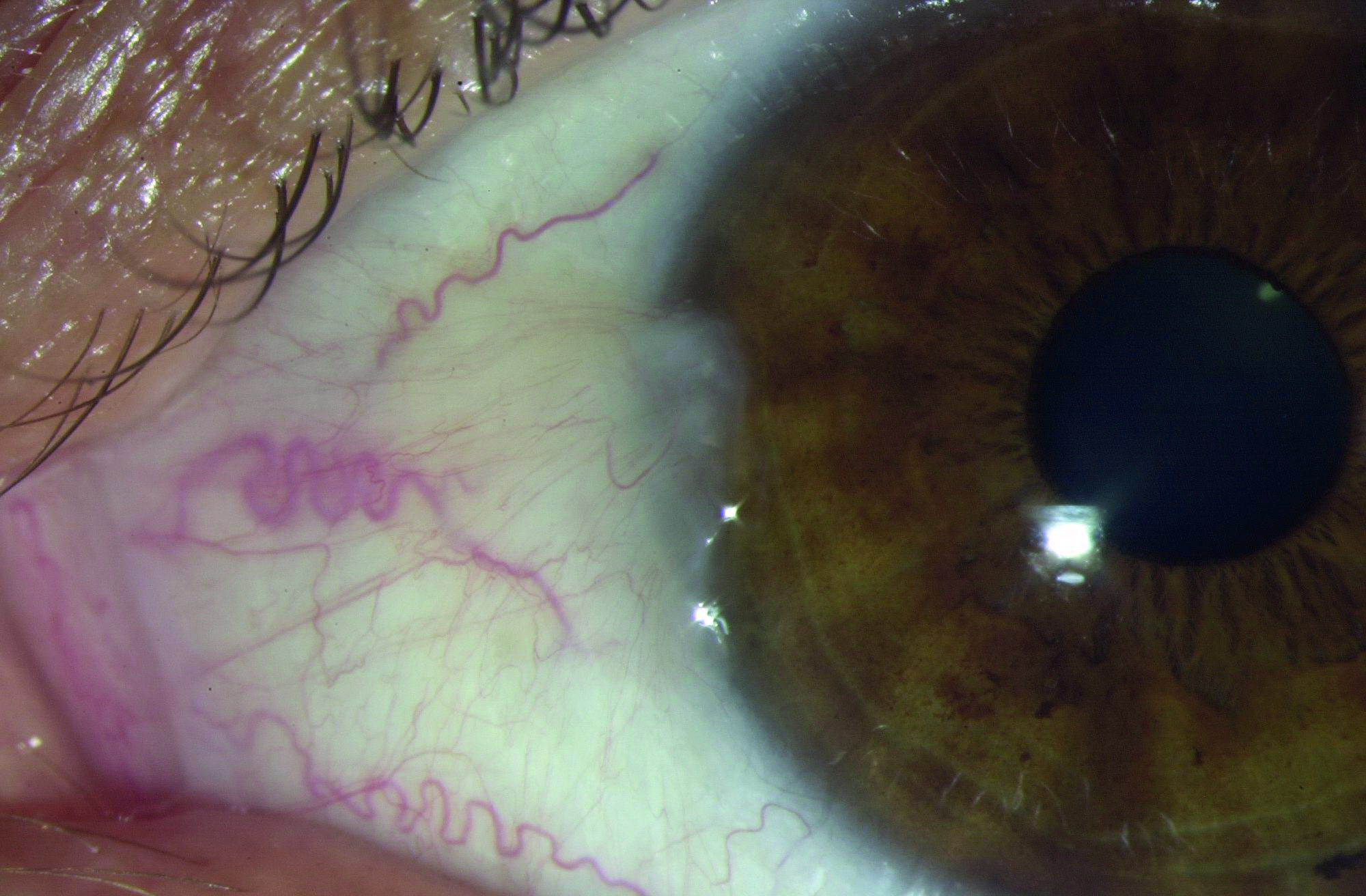

Addressing any tear film abnormalities and ocular surface disease (OSD), as indicated by corneal and conjunctival staining or tear break-up time, is also vital. There may be signs of OSD which have not yet translated into symptoms and the addition of a contact lens may just tip things over the edge. Equally, conjunctival conditions, such as the presence of pinguecula or pterygium (figure 2), and corneal issues such as recurring corneal erosions, could all affect the fit and comfort of the lens, and so thought must be given to these first and foremost.

Figure 2: Pterygium

Fixing the Sub-optimal Contact Lens Factors

The next step of the TFOS flowchart (figure 1) encourages the fixing of sub-optimal contact lens factors.10 In essence, what lens factors could be causing or contributing to CLD for the current contact lens. Are there any obvious lens defects present such as edge chips or tears? These could be causing the discomfort itself, but could also suggest mishandling or perhaps aggressive cleaning, the latter points requiring re-education.

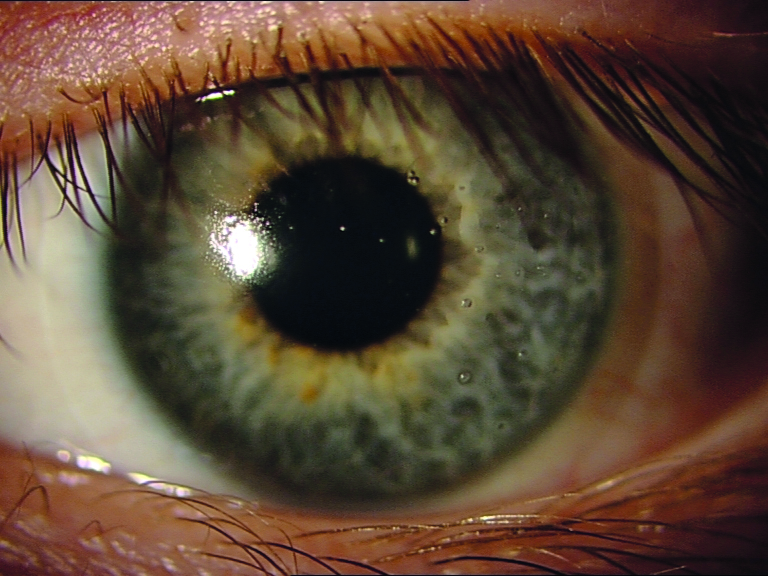

In addition, assessing the lens for deposits is an important observation. Hydrogel lens materials attract more proteins20 and silicone hydrogels attract more lipids (figure 3).21 The accumulation of lipids on the lens suggests a need to reconsider the cleaning methods or modality of wear.

Figure 3: Lipid deposits on a silicone hydrogel lens

It is also important to examine the lens to cornea fitting relationship. How is the lens sitting on the eye? As discussed earlier, is the lens too flat or too steep, both of which could contribute to different degrees of discomfort. Perhaps the lens has just been inserted inside-out; a mistake which is easily remediated. Similarly, the lens and lid interaction is also of importance and, depending on the lens modulus and edge features, can result in edge standoff or fluting in severe cases.22

Lastly, one must consider visual discomfort. A study was conducted a few years ago by Moldonado-Codina et al to look at the association between comfort and vision in soft toric contact lenses.23 The results showed a strong correlation between perceived comfort and subjective vision. In turn, in cases where the vision is compromised, the discomfort may be amplified. Could the patient reporting CLD benefit from a toric correction, or do they require an adjustment to their prescription to optimise vision?

Treatment With a Clinically Acceptable Lens

The focus then shifts to the treatment of the symptomatic contact lens patient with a clinically acceptable lens. There are numerous remedial options as proposed by the TFOS report on CLD,10 once the aforementioned factors have been addressed. These include:

- Adjusting replacement frequency. Since lens deposition can affect wettability and in turn, comfort, more frequent replacement may provide better comfort.24 Thus, switching to daily disposable lenses might be an appropriate solution for some.

- Changing material. Silicone hydrogel lenses may be more comfortable through the day,25 but hydrogel lenses tend to be more elastic. Switching a person from one type to the other may help, although inevitably, changing the material also results in other factors being changed such as the edge profile of the lens.

- Incorporation of internal wetting agents. Soft lenses may be impregnated with wetting agents such as hyaluronic acid (HA) (to increase hydrophilicity) or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) (to improve surface wettability).

- Use of external wetting agents. The pre-lubrication with the likes of methylcellulose or guar as wetting drops, or the addition of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) to the multipurpose cleaning solution, may aid with the comfort of the contact lenses.

- Elimination of the care system. In cases where the cleaning system is not efficient or deposition is an issue, eliminating this by switching to daily disposable lenses could provide a viable solution.

- Lens factors. Thin, knifepoint edge designs appear to provide better comfort than rounded edge designs,26 so changing lens designs might address the issue of CLD.

- Changing the care system. Toxicity from ingredients in the cleaning solution may lead to discomfort, and so switching to an alternative may be an option.

- Use of tear supplements and wetting agents. Lubricants are still the mainstay of treatment options for CLD.27 Rewetting drops such as hypo-osmotic saline, aqueous based drops, lipid-based drops and more commonly, drops with anti-inflammatory ingredients such as Manuka honey, are some of the options available to the patient.

- Nutrition. Advising patients on nutrition may improve the ocular environment and so improve contact lens comfort. Educating patients on consuming less alcohol and more water, additional essential fatty acids (Omega-3/6) to their diets.

- Punctal occlusion. This could help increase tear quantity, and so could allow longer wearing times (figure 4).

- Topical medications. Such as azithromycin and cyclosporine, could help to improve the ocular environment in which the lens sits.

- Environment. Educating the patient and changing modifiable factors that could be contributing to CLD, such as air conditioning, VDU use, air vents in the car, low humidity, etc.

- Blink behaviour. Educating patients, particularly partial blinkers, to consciously blink during the day, or during extended periods of VDU use for example.

- Soft or rigid. If one lens type is not working, switching them to the other may help.

- Reduced wearing time. For those where comfort is an issue, simply reducing the wearing time to a period that is comfortable, may be the answer.

- Orthokeratology or scleral lenses. Alternative contact lens modalities may improve comfort, though individual suitability of these must be assessed.

- Refractive surgery. In cases where CLD is a continuing issue, patients may look to refractive surgery to be free of contact lens and spectacle correction.

- Spectacles. Where all alternatives have been explored, resorting back to spectacles might be the only solution for some.

Figure 4: Punctal occlusion

Improving the CL Experience

The next part of the webinar focused on techniques we can implement in practice to improve the CL experience for the patient. We are all well-equipped in effective communication, but how can we elevate what we say and do in the test room? The following pointers are some suggestions on the conversations we can have with patients to help with their contact lens wear:

- Revisiting handling at each aftercare. It is easy to slip into bad habits over time, which could compromise the safety of contact lens wear. Assessing whether patients wash their hands before lens handling, and how they clean their lenses (if reusable), are just two of the observations that can be made during an aftercare. Education in cases where this is indicated, could not only help with the safety of contact lens wear but potentially improve the comfort.

- Leaflets to supplements advice. Only a small fraction of conversations is retained by the average person. During a consultation when so much is discussed, it is always helpful to supplement advice with leaflets and instructions.

- Open conversations. ‘Silent sufferers’ are a common patient type in practice. Problems may not be reported in fear that the ECP may tell the patient that they are no longer suitable for contact lens wear. Reassuring patients that not all lenses feel the same and that the type of lens may require changing to match the changing needs of the patient, is an important conversation to have. The transparency is part of a healthy patient-practitioner relationship.

- Specific questions. Instead of asking ‘how long do you wear your lenses?’ ask them at what time the lenses are inserted and removed for a more accurate idea of wearing times. For removal of the lenses, asking ‘are the lenses being removed at that time because you want to, or because you have to?’ could suggest comfort issues towards the end of day.

- Offer new technology. There is much emerging technology is the contact lens world at the moment and discussing and offering this to patients who may benefit from this is so important during consultations. If we do not discuss this at contact lens appointments, patients are unaware of their options. Offering free trials of upgrades allows patients to ascertain for themselves, whether the change enhances their contact lens experience.

- Grade comfort out of 10. Something so simple but beneficial. It can give you a numerical idea of the comfort levels, allowing comparisons between visits, between different lens types and even allow monitoring of comfort levels at the beginning and end of the day. Management can then be tailored accordingly.

- Lifestyle changes. Assess lifestyle at each visit. People’s jobs change, their home situation changes and it might be that their current lens choice is not matching their needs anymore.

- Silent cues. Is the patient removing their lenses earlier than previously? Are they using rewetting drops, which they were not using at their last appointment? Are they having to compromise on their wearing time? Picking up on clues through the history and symptoms is an important element of the aftercare as it can tell you that there may be underlying issues that need addressing.

- Telephone appointments. Having touchpoints between visits, particularly in the first few months of contact lens wear when drop out rates are the highest, is a great way to go the extra mile. There may be some embarrassment to report problems, and so being proactive to reach out to the patient would be very welcomed.

- Address adherence. Are the correct protocols being followed to allow safe and comfortable wear? Advising patients on best practice and how this will help them to get the most out of their lenses and avoid complications, can help to build better relationships between patients and practitioners.

Innovations to Aid Comfort

Finally, what innovations are available to help with comfortable lens wear? One lens might not suit everyone, so it is important to look at what technology suits your patient.

One of the innovations is water gradient technology. Researchers thought, instead of having to compromise between one factor or the other, perhaps there are different requirements at the core and at the surface of the contact lens. It is this notion that led to the development of the water gradient technology in Dailies Total1.

There is a gradual transition from the core, which has a low water content and high silicone content, to the surface, which has a high water content and low silicone content. The surface of the lens has a water content that approaches nearly 100%.28 A cross section of such a lens allows visualisation of this transition.29

A typical silicone hydrogel, on the other hand, is composed of the same homogenous polymer throughout the lens, with no change in water content. The purpose of the water gradient technology is to enhance the comfort of the lenses. The combined properties of the lens allow for increased lubricity and wettability,30 and ex vivo studies demonstrate a longer surface moisture break up time.31

Biofinity lenses employ Aquaform Technology. This feature aims to retain moisture in the lens, by hydrating the lens to twice its weight in water,32 supporting the wettability of the lens and in turn, helping with comfort.

Oasys 1 day Max employs TearStable Technology, which aims to reduce tear evaporation33 through the use of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-based wetting agent applied to surface,34 in turn, helping to support the comfort of the lens.33

Ultra One Day lenses use MoistureSeal and Comfort Feel technologies. MoistureSeal involves a two-phase polymerisation process that includes additional hydrophilic components to help retain moisture. The ComfortFeel technology releases conditioners, osmoprotectants and electrolytes to help support the tear film.35

The SmartTears Technology of Dailies Total1 releases a lipid naturally found in the tear film called phosphatidylcholine to help to stabilise the tear film to provide continuous moisture throughout the day.36 The Celligent Technology of Total30 mimics the surface of the cornea, with charged, mobile polymers at the surface resisting lipids and bacteria and sweeping these away.37

Conclusion

What is the ideal contact lens and tear film relationship for comfortable wear? If you think of a perfect marriage, both parties have to contribute to making it perfect. The same can be applied to this relationship; the contact lens itself needs to have good properties and allow biocompatibility, and the ocular surface also needs to be healthy to provide the right environment for the lens to sit in. In the last few decades, the contact lens world has come so far, and it is exciting to think about what is yet to come.

- Dr Alberto Recchioni is a Research Fellow (optometry) at the University of Birmingham and Dr Sunayna Verma Mistry is Professional Education and Development Manager with Alcon.

- To access the online webinar series, go to: www.alconversation.com/alcon-talks-webinar-series

- Part 2 of this review will consider the latest thinking concerning the tear film and ocular surface and how this influences the ideal contact lens for comfortable wear

Alcon Talks in Optician Contact Lens Monthly 2023:

- March: Toric contact lenses

- June: Contact lens comfort

- September: Dry eye disease

- December: Multifocal contact lens options

References

- Nichols JJ et al. 2013. The TFOS international workshop on contact lens discomfort: executive summary. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 54(11), pp.TFOS7-TFOS13

- Chalmers RL et al. 2016. Soft contact lens-related symptoms in North America and the United Kingdom. Optometry & Vision Science, 93(8), pp.836-847

- Siddireddy, JS et al. 2018. The eyelids and tear film in contact lens discomfort. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 41(2), pp.144-153

- Sapkota, K et al. 2015. Common symptoms of Nepalese soft contact lens wearers: A pilot study. Journal of Optometry, 8(3), pp.200-205

- Young, G et al. 2002. A multi-centre study of lapsed contact lens wearers. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 22(6), pp. 516–527

- Pritchard, N et al. 1999. Discontinuation of contact lens wear: a survey. International Contact Lens Clinic, 26(6), pp.157-162

- Sulley, A et al. (2017. Factors in the success of new contact lens wearers. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 40(1), pp. 15–24

- Soft Contact Lens Dropout Study. July 2013. Alcon Data on file

- Nichols, JJ et al. 2013. The TFOS international workshop on contact lens discomfort: executive summary. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 54(11), pp.TFOS7-TFOS13

- Papas, et al. The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: Report of the Management and Therapy Subcommittee. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2013;54(11):TFOS183-TFOS203

- Giannon AG et al. 2012 Annual report on dry eye disease. Contact Lens Spectrum. 2012; 27: 26–30

- Moss SE et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye syndrome. Archives of Ophthalmology, 2000; 118: 1264–1268

- Uchino M et al. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye disease in Japan: Koumi study. Ophthalmology, 2010; 118: 2361–2367

- Chalmers RL et al. Dryness symptoms among an unselected clinical population with and without contact lens wear. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 2006; 29: 25–30.

- Du Toit RS et al. The effects of six months of contact lens wear on the tear film, ocular surfaces, and symptoms of presbyopes. Optometry & Vision Science, 2001; 78: 455–462

- Du Toit RS et al. The effects of six months of contact lens wear on the tear film, ocular surfaces, and symptoms of presbyopes. Optometry & Vision Science, 2001; 78: 455–462

- Stapleton F et al. TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report. Ocular Surface, 2017 Jul;15(3):334-365

- Baudouin C et al. 2010. Preservatives in eyedrops: the good, the bad and the ugly. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 29(4), pp.312-334

- Pisella PJ et al. Prevalence of ocular symptoms and signs with preserved and preservative free glaucoma medication. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2002;86:418-423

- Sindt CW Longmuir RA. Contact lens strategies for the patient with dry eye. Ocular Surface, 2007; 5: 294–307

- Walther H et al. In vitro cholesterol deposition on daily disposable contact lens materials. Optometry & Vision Science, 2016;93(1):36–41

- Ramdass S. Investigating the fluting phenomenon. Contact Lens Spectrum, Volume: 33, Issue: June 2018, page(s): 19

- Maldonado-Codina et al. 2021. The association of comfort and vision in soft toric contact lens wear. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 44(4), p.101387

- Pritchard N et al. Ocular and subjective responses to frequent replacement of daily wear soft contact lenses. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 1996 Jan;22(1):53-9

- Chalmers R et al. Improving contact-lens related dryness symptoms with silicone hydrogel lenses. Optometry & Vision Science, 2008 Aug;85(8):778-84

- Maïssa C et al. Contact lens-induced circumlimbal staining in silicone hydrogel contact lenses worn on a daily wear basis. Eye & Contact Lens 2012 Jan;38(1):16-26

- Stapleton F et al. 2021. BCLA CLEAR-Contact lens complications. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 44(2), pp.330-367

- Alcon data on file

- Dursch TJ et al. 2015. Fluorescent solute-partitioning characterization of layered soft contact lenses. Acta Biomaterialia, 15, pp.48-54

- Alcon data on file

- Alcon data on file

- https://coopervision.com/practitioner/our-products/biofinity-family/biofinity-biofinity-xr

- https://jnjvisionpro.co.uk/products/acuvue-oasys-max-1-day

- https://www.optix-now.com

- https://www.ultraoneday.co.uk/for-eyecare-professionals

- Alcon data on file 2009

- Alcon data on file