On the June 6, the government released figures for 2022 suggesting that the number of gonorrhoea diagnoses were the highest on record and syphilis diagnoses were the highest since 1948. As both of these diseases, and indeed several other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), have known ocular manifestations, any increase in incidence is likely to result in an increase in their associated ocular signs. And with more patients with ocular problems considering their primary eye care professional (ECP) as the first port of call for anterior and adnexal ocular problems, it is important for all ECPs to be able to identify those that might be caused by an STD and, having done so, know what to do.

This short feature offers an overview of the ocular implications for common STDs.

What is an STD?

STDs, sometimes known as sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and formally known as venereal disease (VD), are infections that are passed from one person to another through sexual contact. They are usually spread during vaginal, oral or anal sex, but can spread through other sexual contact involving the penis, vagina, mouth or anus. This is because some STDs, like herpes and HPV, are spread by direct skin contact or fomite transmission.

Some STDs can be passed from a pregnant person to the baby, either via the placenta during pregnancy or directly during parturition. Other ways that STDs may be spread include during breastfeeding, through blood transfusions or by sharing needles.

As the diseases originate from exogenous infective agents, there is a risk of ocular involvement, either from direct external transmission or through secondary influence via internal transmission from the primary systemic infection. Table 1 lists some of the most common STDs known to have varying influence upon eye health.

Table 1: Common sexually transmitted diseases known to affect the eye

Why are STDs in the news?

At the start of this month, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) published data that showed record levels of gonorrhoea and syphilis diagnoses in 2022.1

Gonorrhoea diagnoses increased to 82,592 in 2022, an increase of 50.3% compared to 2021 (54,961) and 16.1% compared to 2019 (prior to the Covid-19 pandemic). This is the highest number of diagnoses in any one year since records began in 1918. Infectious syphilis diagnoses increased to 8,692 in 2022, up 15.2% compared to 2021 (7,543) and 8.1% compared to 2019. This is the largest annual number since 1948.

Further analysis of the statistics revealed a number of patterns in 2022:

- There was a total of 4,394,404 consultations at sexual health services (SHSs), an 8.2% increase compared to 2021 (4,059,608)

- There were 2,195,909 sexual health screenings (diagnostic tests for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis or HIV), an increase of 13.4% compared to 2021 (1,936,455)

- There were 392,453 diagnoses of new STDs among England residents, an increase of 23.8% compared to 2021 (317,022)

- Gonorrhoea and syphilis have returned to the high levels reported in 2019 (prior to the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic)

- Gonorrhoea is increasing in people of all ages, but the rise is highest among young people aged 15 to 24 years

- Infectious syphilis (primary, secondary and early latent) is increasing both among gay, bisexual or other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), and heterosexual people

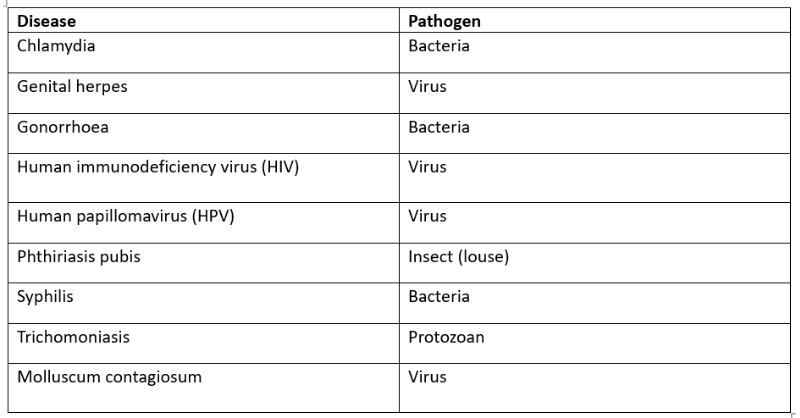

Table 2 summarises the increase for the four main STDs.

One main reason proposed for the increase is a rebound effect after lockdown resulting in a big increase in people accessing sexual health clinic services. That said, there is a clear variation between age, gender and ethnic groups and socioeconomic factors, and changed attitudes to sexual health and healthy sex may also play a role. Figure 1 shows the change in prevalence for common STDs since 2013, and a rise in both gonorrhoea and syphilis is clearly seen.

All of these conditions are avoidable by preventing pathogenic transmission, for example by the use of condoms and maintaining sterile vectors, and all are treatable. That said, the extent and duration of any infection influences the likelihood of lasting damage and illness.

Figure 1: Trends in diagnoses of common STDs over the last decade. The increase in both gonorrhoea and syphilis is clearly seen1

Chlamydia

Chlamydia is a common STD caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis. Most common among young adults (aged 15 to 35 years), the condition is transmitted via oral, vaginal or anal sex with someone who has chlamydia. A pregnant person can also pass the infection to the baby during childbirth. Often asymptomatic, the systemic disease can cause urethritis, cervicitis, prostatitis and proctitis (inflammation of the rectum).

The main ocular impact of chlamydial infection is chronic follicular conjunctivitis (figure 2). Seventy percent of chlamydial conjunctivitis results from sexual activity, the remainder via other direct contact or fomite transmission.

Figure 2: Follicular conjunctivitis

Signs at presentation include:

- Conjunctiva;

- Hyperaemia

- Chemosis

- Mucopurulent discharge

- Follicles, large in the fornices and occasionally seen on the bulbar conjunctiva near the limbus

- Cornea;

- Epithelial keratitis, typically superior

- Infiltrates (figure 3)

Symptomatic relief is often helpful, by issuing ocular lubricants. Contact lens wear must cease. Topical treatment is with tetracycline ointment, typically four times a day for six weeks. Systemic treatment is with either azithromycin (1g single dose) or doxycyline (100mg bid for one to two weeks).

According to the College of Optometrists, clinical management guidelines concerning patients with chlamydial conjunctivitis: ‘It is important that these patients are referred urgently to the ophthalmologist, who will liaise with the genitourinary medicine clinic where the patient can have a full STI investigation. Chlamydial infection is usually treated with antibiotics, which can be very effective. Patients’ sexual partners also may need treatment. Most people with chlamydial infection will be cured if they take their antibiotics correctly.’2

Figure 3: Marginal infiltrates

Genital Herpes

Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by a Herpes simplex virus (HSV). It is characterised by sores in the genital or rectal area, buttocks and thighs. It can be caught from having vaginal, anal or oral sex with someone with the virus. The virus can spread even when sores are not present. Mothers can also infect their babies during childbirth and, due to their nascent immunity, can cause serious illness in the newborn.

There are two types of HSV of relevance, imaginatively called HSV-1 and HSV-2, and each tends to affect different parts of the body. HSV-1 primarily affects areas ‘above the waist’, such as the lips and face (the common cold sore). HSV-2 tends to affect ‘below the waist’, to cause sores around the genitals. These distinctions are not, however, clearcut, and HSV-2 can cause ocular disease.

It is thought that over 90% of the UK population carry HSV, having first caught it via direct contact during childhood (a kiss from an aunt with a cold sore, perhaps). The virus may reside inactive in the nervous system, for example the trigeminal ganglion, until reactivated by any number of possible triggers.

These may include:

- Poor health

- Immunocompromise

- Corticosteroids

- Immunosuppressant drugs

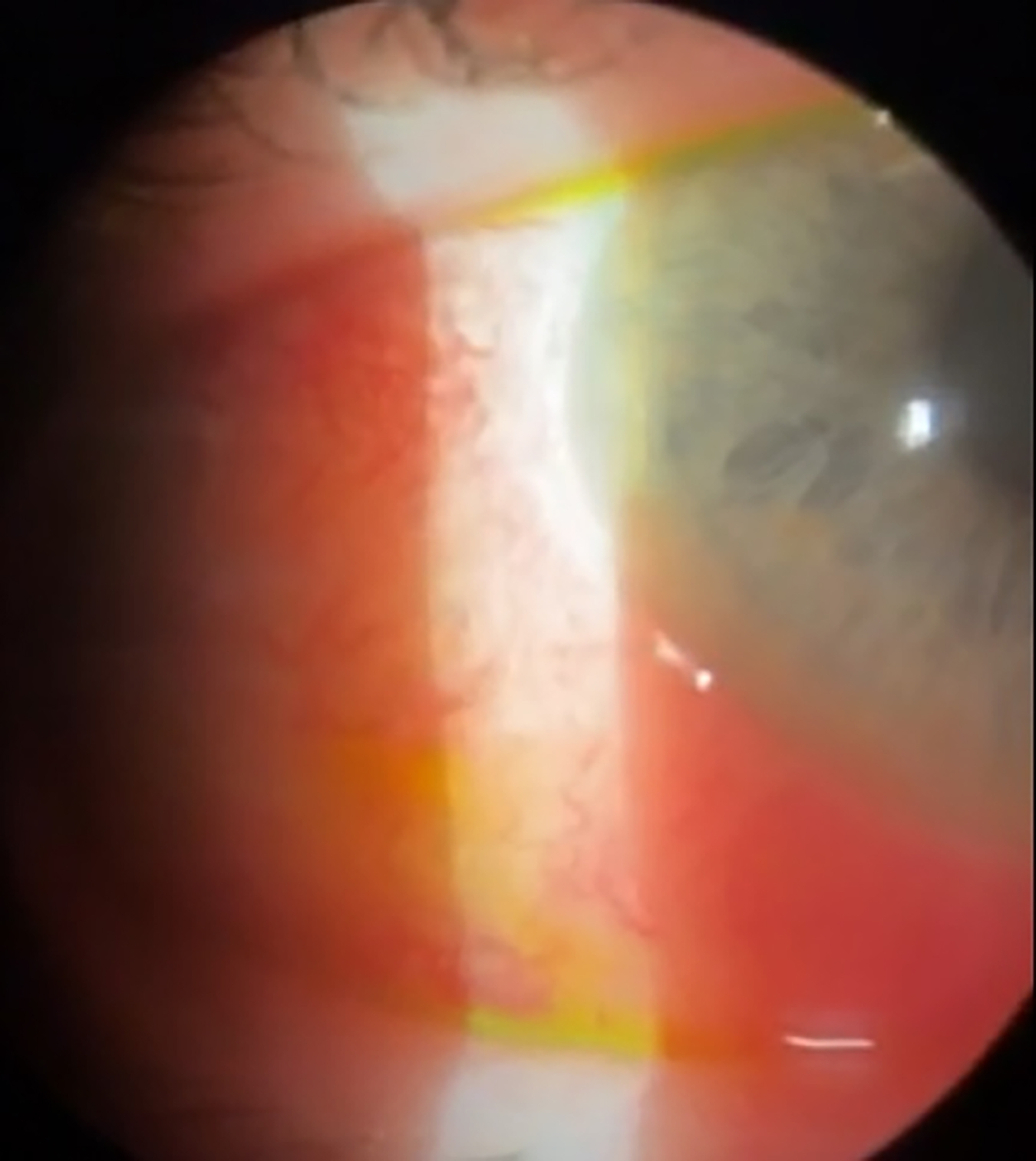

Ocular HSV infection, whether direct or a reactivation of a previous pathogen, can manifest as blepharoconjunctivitis, keratitis, anterior uveitis or acute retinal necrosis. The most common form is epithelial keratitis, accounting for 50% to 80% of cases, and is commonly seen as a characteristic, centrally located dendritic ulceration of the cornea (figure 4). Around 10% of corneal transplants are due to herpetic keratitis.

The condition reminds us of the importance of using fluorescein whenever presented with an apparent viral conjunctivitis as this may reveal the start of a dendritic ulcer. Management is via topical antiviral agents, though anterior chamber involvement (cells and flare) may require steroid drops with antiviral cover. The condition is IP treatable, but any suspicion of retinal involvement or persistence after initial treatment are best sent directly to secondary care.

Figure 4: Dendritic ulcer due to herpetic keratitis

Gonorrhoea

Gonorrhoea is a common STD caused by a Gram-negative bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae. It is transmitted via vaginal, oral, or anal sex with an infected partner. Though not always symptomatic, the STD can cause urethritis, cervicitis, epididymitis, salpingitis (Fallopian tube inflammation) and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). If PID is left untreated in women, it can lead to infertility and neonatal problems.

In men, gonorrhoea can cause pain when urinating and discharge from the penis. If untreated, it can cause problems with the prostate and testicles. In women, the early symptoms often include mild genital discomfort. If ignored, it can cause bleeding between periods, pain when urinating and increased discharge from the vagina.

The conjunctiva is especially prone to invasion by N. gonorrhoea. Once infection is established, the bacteria can rapidly invade the cornea to cause microbial keratitis. The keratitis initially will start at the peripheral cornea causing marginal ulcerations, which can coalesce and, if untreated, may perforate the cornea to cause a devastating endophthalmitis. For this reason, any suspicion of a microbial keratitis in this context warrants an emergency referral (<24 hour).

A pregnant woman can pass it to her baby during childbirth and cause gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum (figure 5) which, if untreated, may lead to loss of sight. Intensive antibiotic treatment is warranted for treatment.

Figure 5: Gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

HIV affects the eye to varying extent in over 70% of cases. The main threat to the eye with HIV is through secondary opportunistic infections, if the complications of some antiretroviral medications are ignored. Ocular complications of note include:

- Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO); affects about 5-15% of HIV patients

- Kaposi sarcoma; a highly vascularised tumour, caused by a human herpes virus (this time, HSV-8), commonly affecting the skin and mucous membranes. It is seen in about 25% of patients who are HIV positive

- More than 50% of HIV-positive patients exhibit anterior segment complications, like dry eyes, keratitis, and iridocyclitis.

- Varicella zoster virus (VZV) and Herpes simplex virus (HSV) are the most common causes of infectious keratitis in HIV-positive patients

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common cause of intraocular infections in Aids patients and CMV retinitis is the most common infectious ocular complication that may affect 30 to 40% of severely immunocompromised individuals

The HIV virus itself may cause a distinct retinopathy seen as multiple cotton wool spots in the absence of significant, visible vascular compromise.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is a member of the papilloma family of viruses that are more commonly found in sexually active patients in their 20s and 30s.

More than 30 to 40 types of HPV are typically spread through sexual contact and infect the anogenital region. Because of an association with malignant disease later in life, a vaccination programme against HPV has been introduced in the UK.

HPV infection of the ocular surface is common but rarely causes problems. That said, it is associated with some malignant diseases such as squamous cell carcinomas.

Phthiriasis pubis

Phthiriasis pubis is caused by pubic lice (commonly known as ‘crabs’) whose leg separation make them easily adapted to life in the pubic hair regions. As the hair separation of the lashes and eye brows is not dissimilar, then direct contact of infected public areas may lead to infestation here too, conditions known as phthiriasis palpebrarum and pediculosis ciliarum respectively.

The lice or their nits can be manually removed using forceps at the slit lamp. Infections of the eyelashes may be managed with petroleum jelly (applied twice daily for 10 days) or 1% permethrin lotion, phenothrin and carbaryl, keeping the eyes closed during the 10 minute application.

Most importantly, signs of phthiriasis in a child must always be treated as a potential safeguarding issue according to your local protocol.

Syphilis

On June 9, 2023, a clinical alert was issued by the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) regarding syphilis. If you see a patient with unknown cause of a red eye condition or visual disturbance you should have a low threshold for suspecting syphilis.

‘If you see a patient with unknown cause of a red eye condition or visual disturbance you should have a low threshold for suspecting syphilis and consider whether you should advise them to have a blood test for syphilis, particularly if they consider themselves in an at-risk group for the disease.’3

Syphilis is a multi-stage, chronic and progressively debilitating disease that is caused by a bacterial spirochaete called Treponema pallidum, which is often transmitted by a sexual route, but can also be transmitted trans-placentally from mother to foetus and by corrupted blood transfusion.4

The eye is not a common site of syphilitic infection. The pathogen usually spreads to the eye through the blood stream. Almost any part of the eye may be involved in syphilis, including the sclera, cornea, lens, uveal tract, retina, retinal vasculature, optic nerve, pupillomotor pathways and cranial nerves. This might present as:

- Mild conjunctivitis; the most likely presentation in primary eye care practice

- Interstitial keratitis; this is non-ulcerative and may be diffuse and bilateral, often with an associated anterior uveitis

- Syphilitic iridocyclitis occurs in about 4% of patients with secondary syphilis

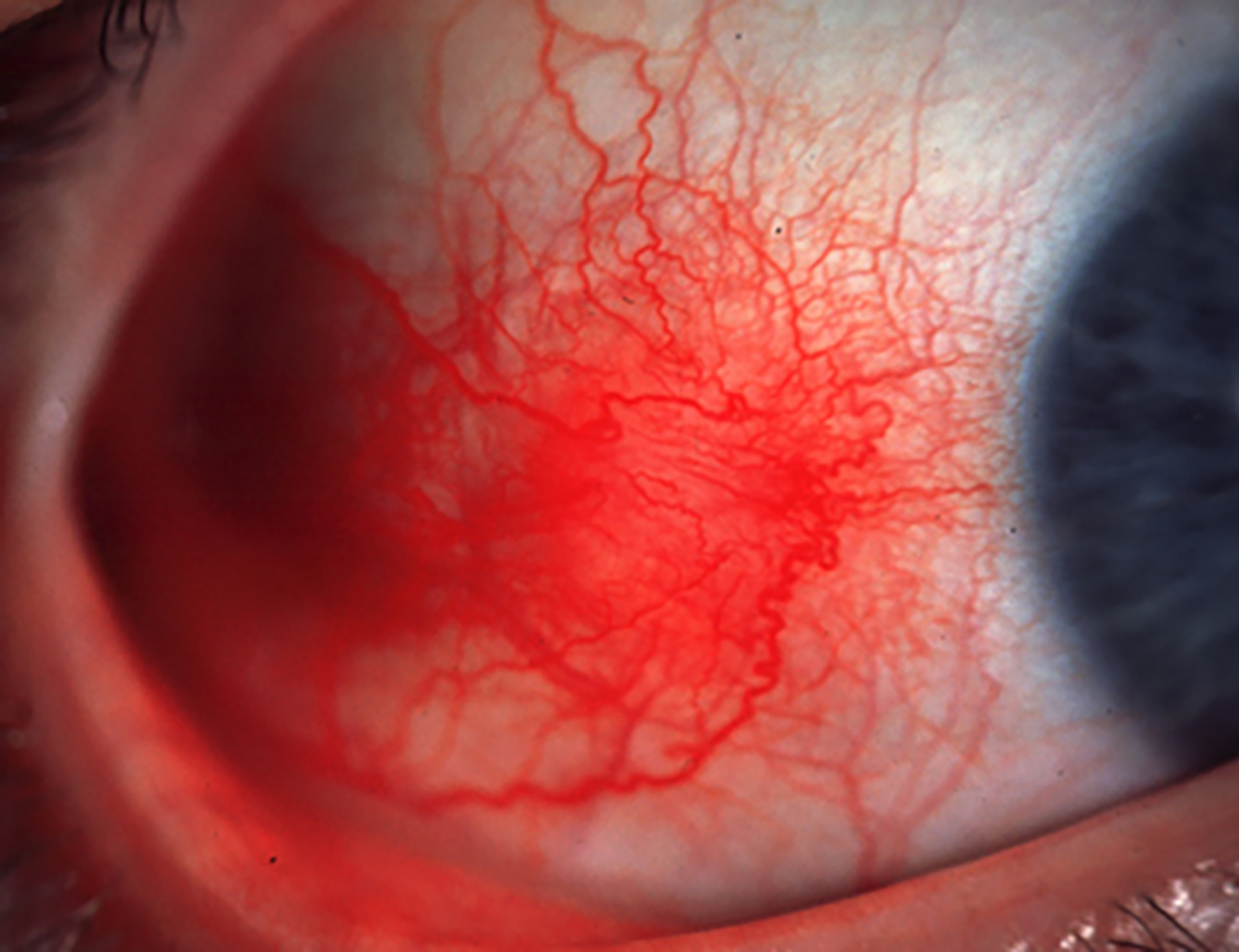

- Episcleritis (figure 6) and scleritis

- 3rd, 4th or 6th nerve palsies

- Argyll Robertson pupil: as per the famous quote, the pupil ‘will accommodate but not react directly’

Despite the worrying increase in the incidence of this serious disease, it must be emphasised that, other than the mild conjunctivitis of unknown origin, most of these signs will be unlikely to first present in primary eye care practice without a previous diagnosis having been made. That said, we all must be aware of the condition and its ocular consequences. And remember, too, that it is treatable, often with a simple course of penicillin if detected early.

Figure 6: Episcleritis

A Final Thought

As with most diseases, prevention of STDs is, by far, preferable to the cure. Primary care clinicians must be better able to dispense sensible advice regarding safer sex, whenever it is appropriate and whether it is to family, friends or our patients.

References

- https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/sexually-transmitted-infections-stis-annual-data-tables/sexually-transmitted-infections-and-screening-for-chlamydia-in-england-2022-report#:~:text=in%202022%20there%20were%20392%2C453,(COVID%2D19)%20pandemic (Accessed June 2023)

- https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/conjunctivitis_chlamydial_adultinclusionconjunctiv (Accessed June 2023)

- https://www.college-optometrists.org/news/2023/june/clinical-alert-syphilis-bashh

- Alwadani F. Common ocular manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 2018, 9:1

Useful Resources

To find out the nearest sexual health clinic, simply type in a postcode at: nhs.uk/service-search/find-a-sexual-health-clinic