It is still the case that many people dropout of contact lens wear, and the reasons for doing so are different between new and established wearers. Given the investment of time from both the eye care professional (ECP) and patient to trial contact lenses, reach a final prescription, be taught wear and care practices, and become a confident happy lens wearer, it is particularly disappointing when new wearers lapse.

Much is understood about their reasons for doing so, and a recent literature review has not only summarised that evidence but has also provided clinical management recommendations for ECPs to use in practice to help take proactive steps to reduce early dropout.1

This article summarises the key points that drive new wearer soft lens dropout and presents clinical management steps that ECPs can take to mitigate these issues.

Dropout from lens wear

Contact lens dropout has been featured in the literature over the past 30 years and the dropout rate has remained fairly stable over this period despite efforts, including new lens design and material technology, to help reduce it.2-12 When a lens wearer discontinues contact lens use, it is typically considered a clinical failure, as significant resources have been invested in the fitting process.

Those resources comprise the time and effort of the clinical staff, support team and of the lens wearer themselves. Stopping wear is often disappointing for the patient, who is missing out on the vision and lifestyle benefits of contact lenses, the ECP and practice staff but also for the contact lens industry as a whole, as a high rate of global discontinuation can limit market size and investment in new materials and designs.

The incidence of contact lens dropout and examination of common reasons

A survey of over 4,000 existing and new contact lens wearers by Dumbleton et al noted that discomfort or dryness accounted for around half of all discontinuations.4 Other factors such as vision, handling, expense, lens maintenance, infections, allergies and pregnancy each accounted for approximately 5% of dropouts. The overall dropout rate (existing and new wearers) found by pooling multiple studies was found to be 21.7% per year.13

Specific studies looking at new contact lens wearers only were conducted by Sulley and co-workers. They performed a prospective study over one year8 and a retrospective chart review.2 The two most significant reasons reported by new wearers who discontinued were poor vision and handling.2 The dropout rates for new wearers were found to be 22-26% per year2, 8 which are higher than the overall rate, indicating that new wearers specifically seem to be more at risk of discontinuation.

When do new lens wearers dropout?

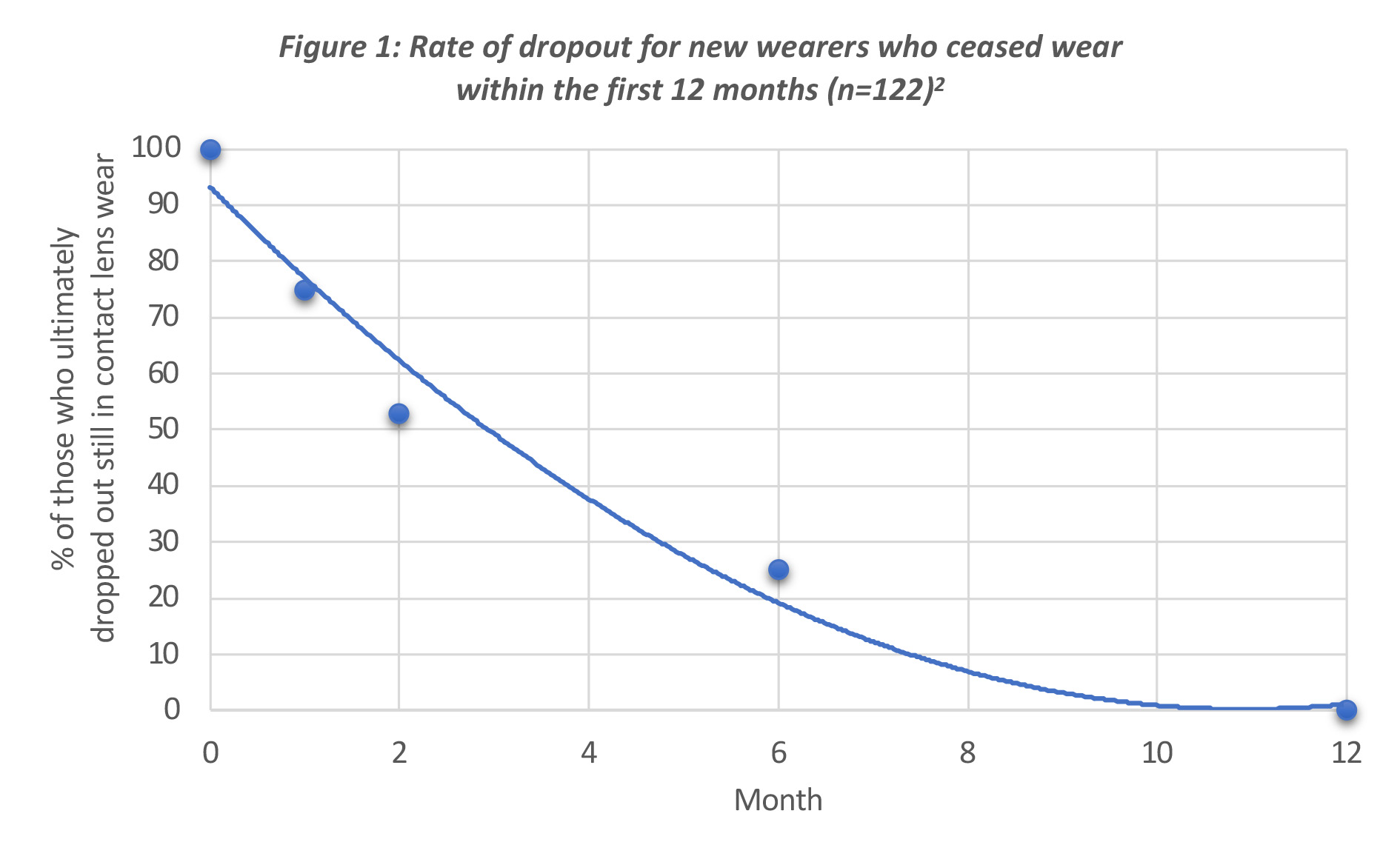

It is of interest to understand when new wearers dropout. In the retrospective study, of the wearers who dropped out at a known time point, nearly half of them (47%) did so within the first two months.2, 8 The rate of dropout from this review is depicted in figure 1, which shows the proportion of the 122 wearers from this dropout group by month across the year. While this group all ultimately ceased lens wear, the early few weeks are critical, with the steepest decline in wearers occurring here.

Figure 1: Rate of dropout for new wearers who ceased wear within the first 12 months (n=122)2

These first two months are critical to the success of new contact lens wearers. The understanding that vision and handling are significant factors, along with the comfort experience is key. By developing targeted communication and associated clinical management strategies, ECPs and practice teams should be able to assist new wearers and reduce discontinuations.

Evidence

Vision

This was rated as an important reason for new wearer discontinuation.2 Evidence confirms the need for accurate refraction and that just a 0.25D optical blur is associated with the loss of one line of logMAR acuity.14 For soft toric lenses, visual stability is a crucial factor to consider as different toric lens designs can produce variations in visual performance.15, 16 Sulley and colleagues have shown that soft multifocal lens wearers are more likely to drop out versus spherical and toric wearers.2

This further emphasises the importance of visual performance in contact lens wearer success. Symptoms of poor vision can sometimes be perceived by wearers as symptoms of discomfort.17-19 In fact, many new lens wearers do not inform their ECPs about their sub-optimal vision or comfort and continue to struggle at risk of discontinuation.20, 21

Most of these ‘strugglers’ are frustrated with their lenses and develop compensations such as removing lenses early or using re-wetting drops without informing their ECPs.20 There is some evidence to show that phoning or sending supportive SMS messages to new lens wearers is associated with a reduction in discontinuations.22, 23

Discomfort

Discomfort is the main reason for discontinuation across all CL wearers,4 yet for new wearers it is less of a significant factor over the first few weeks of wear.2 Evidence confirms that many contact lens wearers notice their lenses are less comfortable at the end of the day. It is worth noting that non-contact lens wearers also report a reduction in comfort towards the end of the day,24 so some reduction in ocular comfort is normal for spectacle wearers and emmetropes too.

Unfortunately, even after a full review by the Tear Film and Ocular Surface (TFOS) society in 2013, there is still much that is unknown about the impact of lens parameters on discomfort.25 The majority of clinical trials compare one lens against another with poor control of variables and in vitro laboratory testing results seem to poorly predict real on-eye lens performance.25

Evidence points to a relationship between reduced lens movement on the eye26, 27 and tapered lens edge profiles28, 29 leading to greater comfort. There is also evidence that shows different reusable lens/solution combinations can vary comfort levels.30 Comfort is generally improved with daily disposables compared to reusable lenses31 and also with the addition of lipid-containing re-wetting drops.32

There is supportive evidence that increased comfort is linked to individual factors of low friction (lubricity),33, 34 lens wettability,35 and low water content.36 There is evidence that a balanced supplementation of omega 6 and omega 337 fatty acids can improve ocular comfort whereas low humidity environments38 and use of visual display units,39, 40 is associated with reduced comfort.

Handling

Evidence points to handling being a major cause of contact lens discontinuation in new wearers.2 In a recent survey, two thirds of daily disposable wearers reported some difficulty with overall handling,41 and in another study, the ability to remove a contact lens easily was associated with improved satisfaction.42 Important features such as lens material, lens power, visibility tint, lens design, inversion indicators and blister pack characteristics may impact lens handling, however there is little direct evidence in this area.43, 44

Training new lens wearers to handle and care for their lenses is a very important part of the fitting process and anecdotally there are many different approaches undertaken in clinical practice such as lens application onto cornea versus sclera and the number of times lenses should be applied and removed before training is considered complete.

However, once again, there is minimal direct evidence as to which method is the best and it is most likely a tailored approach that provides the most success. Evidence confirms that contact lens case compliance is better when wearers are provided written instructions45 and lens hygiene appears to be improved when ‘no-water’ stickers are applied to the lens case.46

Sulley and co-workers found that new wearer retention rates in practice varied from 40% to 100% and there was no link between type, nature or location of the practice and the retention rate.2 Purchase frequency was linked to retention rate suggesting the importance of local (in-practice) systems such as advocating quarterly lens supply vs ad hoc purchasing.2 These examples demonstrate it appears within the remit of the individual practice and practice team to approach their support of new wearers in such a way that can make a significant reduction in likelihood to dropout.

Inconvenience and loss of interest

New contact lens wearers can dropout due to reduced interest in their lenses or perceived inconvenience.2, 8 Reduced interest may be because of lens problems such as those described above, or because the lenses are only needed for a specific event such as a wedding or holiday. Changes in lifestyle, like working from home, may also reduce interest in contact lenses.47, 48

Inconvenience may include factors such as the time or space required for contact lens care. Mental health issues and other non-contact lens considerations may also play a role in satisfaction and discontinuation.47, 48 Daily disposable lenses have been shown to be generally more convenient and associated with increased compliance versus reusables.49-51

Concerns around ocular health and contact lens complications

Concerns around ocular health and contact lens complications are infrequently reported as a reason for lens discontinuation.2 For most common contact lens complications, temporary cessation of lens wear is often recommended as part of the management.52 It is possible that a minor complication experienced in a new wearer could dissuade them from starting lens wear once the condition has recovered. Other concerns that may be front of mind for new lens wearers are the risks of contact lens-related infection.53

Cost

Some people discontinue using contact lenses due to the cost associated with their wear, although it is not a very common reason.2, 4 While most new lens wearers are aware of the expenses involved, a small percentage may experience ‘buyer’s remorse’ due to difficulties such as handling, vision, or comfort, perhaps ultimately feeling the benefits of lens wear do not sufficiently offset the cost in their case.

Environmental concerns

As sustainability becomes of increasing interest to consumers, contact lens wearers show greater concerns about the disposability and environmental impact of wearing contact lenses. There have been press reports referring to contact lenses being flushed down the lavatory or sink and ending up in waste water systems.54

However, research conducted in the UK reports that full-time contact lens wear makes up only 0.2% of the waste produced per year per person with little difference in overall waste between daily disposable and frequently replaced lenses and their associated cleaning solutions.55 This context can be helpful to share with patients.

Clinical Management Strategies

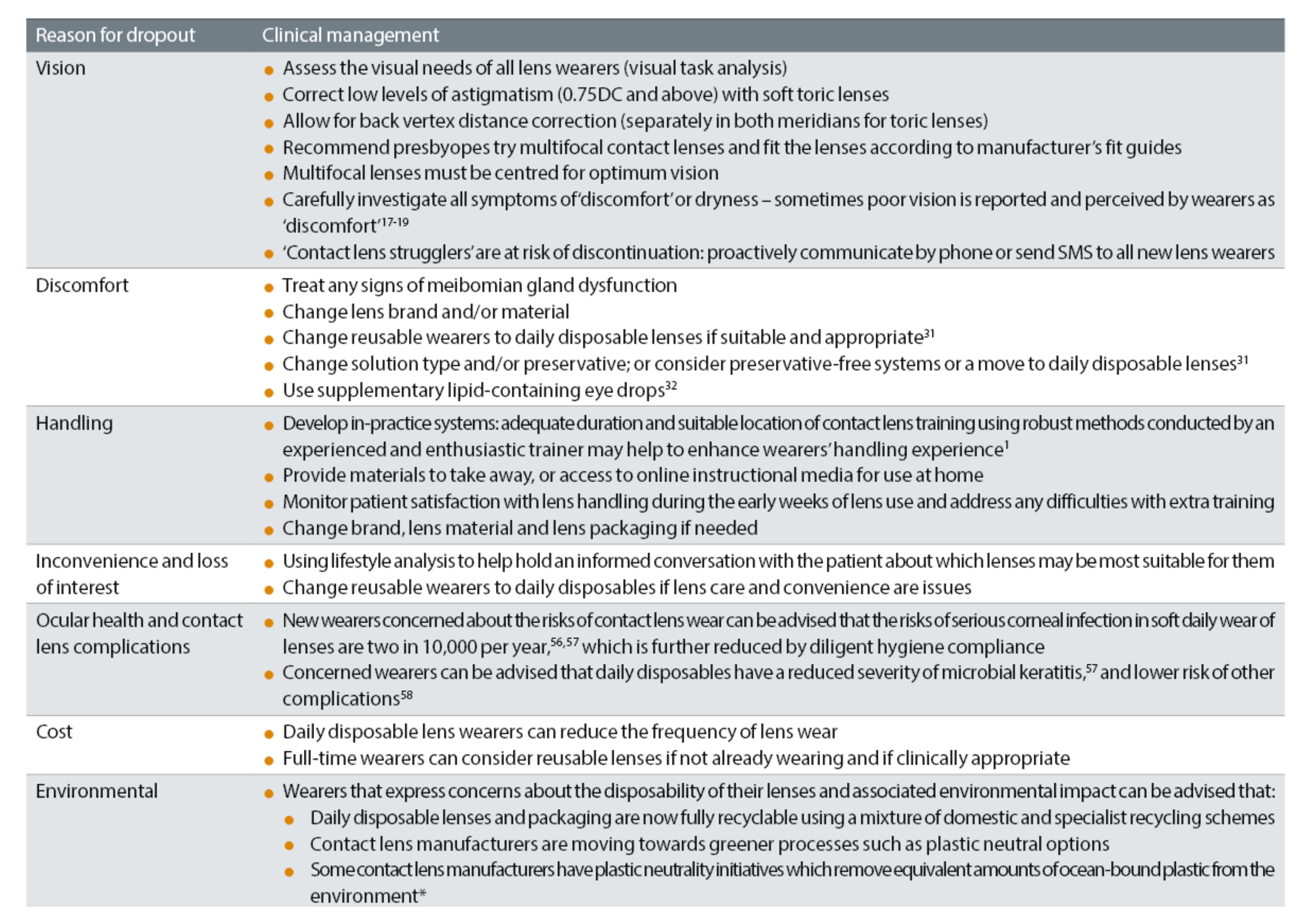

For each of the reviewed reasons for new wearer dropout, there are proactive actions the ECP and practice can take to help reduce the chance of problems occurring, which may lead to stopping contact lens wear. These are summarised in table 1 and reviewed in more detail in this section.

Table 1: Evidence based clinical management strategies for new soft contact lens wearers

Vision

It is understood that vision plays a very important role in retaining new wearers and for this reason, it is imperative to assess the visual needs of all new wearers. Evidence shows that astigmatism, where present, must be corrected and even low levels of astigmatism (-0.75 and -1.00DC) should be corrected using toric lens designs for optimum acuity,59, 60 usually without the need for additional chair time.61

Remember to optimise vision by allowing for back vertex distance correction with all lenses, and separately in both meridians for toric lenses.

Multifocal wearers must be fitted with sufficiently performing lenses and then adjustments made62, 63 with the aid of manufacturers fitting guides. Multifocal lenses that centre well64 and visual assessment using feedback from habitual ‘real-world’ tasks as well as static acuity measures is important.65, 66 There is evidence to show different methods of communication reduces dropout,22, 23 however, as discussed earlier, many contact lens ‘strugglers’ do not inform their ECPs about their difficulties.

Therefore, it seems valuable to adopt a communication management strategy of proactively communicating and supporting all new lens wearers using phone calls and/or supportive SMS messages over the first two months. This is something the support team can be tasked with doing in many practices.

Discomfort

Lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation may prove too difficult or unrealistic to enforce, however, there is growing evidence that treating any signs of meibomian gland dysfunction is useful for improving comfort.67-69 For discomfort with a particular lens, changing the lens brand and/or material to attain a lens, that for the average wearer, delivers reduced movement and greater lubricity should generate improvements.

Changing solution types30 and using supplementary lipid-containing re-wetting drops32 could be useful for the average lens wearer. If a modality change is suitable and appropriate, then moving from reusable lenses to daily disposable lenses can help with comfort.31

Handling

Patient satisfaction with lens handling should be monitored during the early weeks of lens use and any difficulties should be addressed with extra training using phone/video call advice or in practice follow-up visits as well as directing patients to online resources. Evidence seems to point to the development of in-practice systems and procedures that enhance wearers handling experience.2

Currently the management strategies of changing lens brand, lens material and lens packaging are available, however, more evidence is needed to develop an exact protocol leading to improved handling. Its seems logical that adequate duration and quiet location of contact lens training using robust methods conducted by an experienced and enthusiastic trainer would help with patient success.1

Inconvenience and loss of interest

Reusable lens wearers contending with potentially frustrating lens care regimens involving multiple steps51 may benefit from changing to daily disposable lenses. Daily disposables are generally simpler to use and wearers have improved compliance,49 which should reduce the likelihood of discontinuation. While daily disposable lenses offer convenience, there are wearers who report inconvenience with this modality.8

Extended wear is an option for those who dislike daily application, however, increased rate of corneal infection compared to daily wear56, 57, 70 and associated reduced ECP confidence potentially limits this option as a viable management strategy for many.

Ocular health and contact lens complications

New wearers who are concerned about their ocular heath with contact lens wear can be reassured that the risks of microbial keratitis in daily contact lens wear are two in 10,000 per year56, 57 and that this risk is further reduced by diligent hygiene compliance with lens wear.49 Concerned wearers can also be advised that daily disposables have a reduced severity of microbial keratitis57 and overall a lower risk of other complications such as corneal infiltrative events,58 corneal staining and papillary conjunctivitis.71, 72

Cost

Toric lenses and multifocal lenses are more expensive than spherical lenses. However, it is important to ensure the prescribed lens is based on visual need and that it delivers accurate correction of vision for the wearer. The clinical management option of reducing the frequency of lens wear in daily disposables will evidently cut the cost of wear. Daily disposables are suitable and prescribed often for part time wear.73, 74 If clinically appropriate, full time daily disposable wearers can be fitted with more cost effective reusable lenses.75, 76

A survey of habitual contact lens wearers in the US provides an understanding of the value they place on their lenses, which may guide our price conversations with new wearers.77 Surveyed wearers indicated they would rather give up alcohol and cinema and would choose to dine out less frequently before giving up their contact lenses.77

Environmental issues

Some wearers may have concerns about the disposability of contact lenses and the impact of this waste on the environment. Concerned lenses wearers can be advised that contact lenses make up a very small proportion (0.2% per person) of yearly household waste55 and that daily disposable lens systems (including packaging) are now fully recyclable.

Wearers can be directed to carry out recycling using a mixture of domestic (council waste) and specialist systems (via optometric practices and manufacturer schemes). In addition, manufactures are moving towards greener processes like plastic neutral options.

Summary

Of the population that needs refractive error correction, only 2% use contact lenses.78 There are clearly potential lens wearers who have never tried and lens wearers who have been unsuccessful. Understanding the common pitfalls experienced by new wearers is key to helping them become successful long-term wearers.

The evidence-based options for clinical management strategies are listed above and are relatively simple and intuitive. The evidence points to close contact between new lens wearer and the ECP/practice involving calling or sending SMS messages to new lens wearers particularly during the first two months of wear. This seems a practical and delegable strategy within the practice team.

As ever, careful questioning and prompting during follow up visits to discover potential difficulties or reasons for proposed discontinuation is important so that the correct clinical management strategy can then be applied.

It is understood that using contact lenses can increase patient reported quality of life outcomes including individuals self-perception and confidence.79 It is also clear that many of the factors that are implicated in new lens wearer discontinuation are indeed modifiable and within the control of the ECP and practice team.

Addressing these factors should lead to greater numbers of contented lens wearers, more satisfied ECPs and greater success for individual practices and the contact lens industry.

- Adam Samuels is an experienced optometrist and Scientia PhD candidate at UNSW Sydney. Adam’s research includes contact lens dropout and behaviour change application in the field of contact lens compliance.

- Philip Morgan is Professor of Optometry, Head of Optometry, Deputy Head of the Division of Pharmacy and Optometry, and Director of Eurolens Research at The University of Manchester.

- Optometrist Anna Sulley has held various positions within the contact lens industry involving research, medical, professional, education and clinical roles and is currently Director of Global Medical Affairs at CooperVision. Anna has authored numerous publications and conference presentations, is Past President of the British Contact Lens Association (BCLA), and a Fellow for both the BCLA and American Academy of Optometry.

Footnotes

* Net plastic neutrality is established by purchasing credits from Plastic Bank. A credit represents the collection and conversion of one kilogram of plastic that may reach or be destined for waterway. CooperVision purchases credits equal to the weight of plastic in participating brand orders in a specified time period. Plastic in participating brand orders is determined by the weight of plastic in the blister, the lens, and the secondary package, including laminates, adhesives, and auxiliary inputs (eg ink).

References

- Morgan, PB and AL Sulley, Challenges to the new soft contact lens wearer and strategies for clinical management. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2023: p. 101827.

- Sulley, A, G Young, and C Hunt, Factors in the success of new contact lens wearers. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2017. 40(1): p. 15-24.

- Santodomingo-Rubido, J, JS Wolffsohn, and B Gilmartin, Adverse events and discontinuations during 18 months of silicone hydrogel contact lens wear. Eye & contact lens, 2007. 33(6 Part 1 of 2): p. 288-292.

- Dumbleton, K, et al, The impact of contemporary contact lenses on contact lens discontinuation. Eye & contact lens, 2013. 39(1): p. 93-99.

- Weed, K, D Fonn, and R Potvin, Discontinuation of contact lens wear. Optom Vis Sci, 1993. 70(12s): p. 140.

- Young, G, et al, A multi-centre study of lapsed contact lens wearers. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 2002. 22(6): p. 516-527.

- Pritchard, N, D Fonn, and D Brazeau, Discontinuation of contact lens wear: a survey. International Contact Lens Clinic, 1999. 26(6): p. 157-162.

- Sulley, A, et al, Retention rates in new contact lens wearers. Eye & contact lens, 2018. 44: p. S273-S282.

- Richdale, K, et al, Frequency of and factors associated with contact lens dissatisfaction and discontinuation. Cornea, 2007. 26(2): p. 168-174.

- Morgan, PB, et al, Adverse events and discontinuations with rigid and soft hyper Dk contact lenses used for continuous wear. Optometry and vision science, 2005. 82(6): p. 528-535.

- Chalmers, RL, et al, Struggle with hydrogel CL wear increases with age in young adults. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2009. 32(3): p. 113-119.

- McMonnies, CW, Why are soft contact lens wear discontinuation rates still too high? Expert Review of Ophthalmology, 2022(just-accepted).

- Pucker, AD and AA Tichenor, A Review of Contact Lens Dropout. Clinical optometry, 2020. 12: p. 85-94.

- Radhakrishnan, H, et al, Unequal reduction in visual acuity with positive and negative defocusing lenses in myopes. Optometry and Vision Science, 2004. 81(1): p. 14-17.

- Chamberlain, P, et al, Fluctuation in visual acuity during soft toric contact lens wear. Optometry and vision science, 2011. 88(4): p. E534-E538.

- Tomlinson, A, W Ridder 3rd, and R Watanabe, Blink-induced variations in visual performance with toric soft contact lenses. Optometry and Vision Science: Official Publication of the American Academy of Optometry, 1994. 71(9): p. 545-549.

- Diec, J, et al, The relationship between vision and comfort in contact lens wear. Eye & Contact Lens, 2021. 47(5): p. 271-276.

- Maldonado-Codina, C, et al, The association of comfort and vision in soft toric contact lens wear. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2021. 44(4): p. 101387.

- Rao, SBS and TL Simpson, Influence of vision on ocular comfort ratings. Optometry and vision science, 2016. 93(8): p. 793-800.

- Veys, J and A Sulley, Pay attention to retention. Optician, 2017. 2017(5): p. 5693-1.

- Nichols, KK, et al, The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, 2013. 54(11): p. TFOS14-TFOS19.

- Cooney, E and P Morgan, The impact on retention figures of the introduction of a comfort call during a contact lens trial. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2018. 41: p. S66.

- Patel, K, The impact on new contact lens wearer retention after introduction of a patient support tool. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2022. 45(1).

- de la Jara, PL, et al, Measuring daily disposable contact lenses against nonwearer benchmarks. Optometry and Vision Science, 2018. 95(12): p. 1088-1095.

- Nichols, JJ, et al, The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: Executive Summary. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science, 2013. 54(11): p. TFOS7.

- Hoekel, JR, et al, An evaluation of the 8.4 mm and the 8.8 mm base curve radii in the Ciba NewVe vs. the Vistakon Acuvue. International Contact Lens Clinic, 1994. 21(1-2): p. 14-18.

- Truong, TN, AD Graham, and MC Lin, Factors in contact lens symptoms: evidence from a multistudy database. Optometry and Vision Science, 2014. 91(2): p. 133-141.

- Hübner, T, M Tamm, and W Sickenberger. Fitting characteristics of commercially available disposable contact lenses regarding their edge designs. in BCLA Meeting. 2009.

- Maïssa, C, M Guillon, and RJ Garofalo, Contact lens–induced circumlimbal staining in silicone hydrogel contact lenses worn on a daily wear basis. Eye & contact lens, 2012. 38(1): p. 16-26.

- Tilia, D, et al, Effect of lens and solution choice on the comfort of contact lens wearers. Optometry and Vision Science, 2013. 90(5): p. 411-418.

- de la Jara, PL, et al, Effect of lens care systems on the clinical performance of a contact lens. Optometry and Vision Science, 2013. 90(4): p. 344-350.

- Pucker, AD, et al, Evaluation of systane complete for the treatment of contact lens discomfort. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2020. 43(5): p. 441-447.

- Coles, C and N Brennan, Coefficient of friction and soft contact lens comfort. Optom Vis Sci, 2012. 88.

- Kern, J, et al, Assessment of the relationship between contact lens coefficient of friction and subject lens comfort. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, 2013. 54(15): p. 494-494.

- Keir, N and L Jones, Wettability and silicone hydrogel lenses: a review. Eye & Contact Lens, 2013. 39(1): p. 100-108.

- Young, G, Evaluation of soft contact lens fitting characteristics. Optometry and vision science, 1996. 73(4): p. 247-254.

- Downie, LE, et al, Modulating contact lens discomfort with anti-inflammatory approaches: a randomized controlled trial. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, 2018. 59(8): p. 3755-3766.

- Dumbleton, K, et al, The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: report of the subcommittee on epidemiology. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, 2013. 54(11): p. TFOS20-TFOS36.

- González-Méijome, JM, et al, Symptoms in a population of contact lens and noncontact lens wearers under different environmental conditions. Optometry and Vision Science, 2007. 84(4): p. E296-E302.

- Uchino, M, et al, Prevalence of dry eye disease among Japanese visual display terminal users. Ophthalmology, 2008. 115(11): p. 1982-1988.

- Retallic, N and M Nagra, Getting to grips with soft contact lens handling. Optician Select, 2022. 2022(2): p. 8876-1.

- Guthrie, S, et al, Exploring the factors which impact overall satisfaction with single vision contact lenses. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2022. 45(5): p. 101579.

- Brennan, NA, et al, A 12-month prospective clinical trial of comfilcon A silicone-hydrogel contact lenses worn on a 30-day continuous wear basis. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2007. 30(2): p. 108-118.

- Brennan, NA, et al, A 1-year prospective clinical trial of balafilcon a (PureVision) silicone-hydrogel contact lenses used on a 30-day continuous wear schedule. Ophthalmology, 2002. 109(6): p. 1172-1177.

- Tilia, D, et al, The effect of compliance on contact lens case contamination. Optometry and vision science: official publication of the American Academy of Optometry, 2014. 91(3): p. 262.

- Arshad, M, et al, Compliance behaviour change in contact lens wearers: a randomised controlled trial. Eye, 2020.

- Morgan, PB, Contact lens wear during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2020. 43(3): p. 213.

- Nagra, M, N Retallic, and SA Naroo, The impact of COVID-19 on soft contact lens wear in established European and US markets. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2022. 45(6): p. 101718.

- Morgan, PB, et al, An international analysis of contact lens compliance. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2011. 34(5): p. 223-228.

- Ichijima, H, et al, Improvement of subjective symptoms and eye complications when changing from 2-week frequent replacement to daily disposable contact lenses in a subscriber membership system. Eye & Contact Lens, 2016. 42(3): p. 190-195.

- Young, G, Diligent disinfection in 49 steps. Contact Lens Spectrum, 2012. 27(2): p. 53-4.

- Stapleton, F, et al, CLEAR - Contact lens complications. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2021. 44(2): p. 330-367.

- Cardona, G, S Alonso, and S Yela, Compliance versus risk awareness with contact lens storage case hygiene and replacement. Optometry and Vision Science, 2022. 99(5): p. 449-454.

- M, M, Plastic pollution: “Stop flushing contact lenses down the loo.”. BBC Media, 2018.

- Smith, SL, et al, An investigation into disposal and recycling options for daily disposable and monthly replacement soft contact lens modalities. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2022. 45(2): p. 101435.

- Dart, JKG, et al, Risk Factors for Microbial Keratitis with Contemporary Contact Lenses. Ophthalmology, 2008. 115(10): p. 1647-1654.e3.

- Stapleton, F, et al, The Incidence of Contact Lens–Related Microbial Keratitis in Australia. Ophthalmology, 2008. 115(10): p. 1655-1662.

- Chalmers, R, et al, Multicenter case-control study of the role of lens materials and care products on the development of corneal infiltrates. Optometry and vision science, 2012. 89(3): p. 316-325.

- Richdale, K, et al, Visual acuity with spherical and toric soft contact lenses in low-to moderate-astigmatic eyes. Optometry and Vision Science, 2007. 84(10): p. 969-975.

- Morgan, PB, et al, Inefficacy of aspheric soft contact lenses for the correction of low levels of astigmatism. Optometry and vision science, 2005. 82(9): p. 823-828.

- Smith, S, et al, Chair time required for the fitting of various soft contact lens designs. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2022. 45(1).

- Papas, EB, et al, Utility of short-term evaluation of presbyopic contact lens performance. Eye & contact lens, 2009. 35(3): p. 144-148.

- Woods, J, CA.Woods, and D Fonn, Early symptomatic presbyopes—what correction modality works best? Eye & contact lens, 2009. 35(5): p. 221-226.

- Fedtke, C, et al, Visual performance of single vision and multifocal contact lenses in non-presbyopic myopic eyes. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2016. 39(1): p. 38-46.

- Jong, M, et al, The relationship between visual acuity, subjective vision, and willingness to purchase simultaneous-image contact lenses. Optometry and Vision Science, 2019. 96(4): p. 283-290.

- Legras, R, M Vincent, and G Marin, Does visual acuity predict visual preference in progressive addition lenses? Journal of Optometry, 2022.

- Blackie, CA, et al, A single vectored thermal pulsation treatment for meibomian gland dysfunction increases mean comfortable contact lens wearing time by approximately 4 hours per day. Clinical ophthalmology, 2018: p. 169-183.

- Siddireddy, JS, et al, Effect of eyelid treatments on bacterial load and lipase activity in relation to contact lens discomfort. Eye & contact lens, 2020. 46(4): p. 245-253.

- Tichenor, AA, et al, Effect of the Bruder moist heat eye compress on contact lens discomfort in contact lens wearers: an open-label randomized clinical trial. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2019. 42(6): p. 625-632.

- Morgan, PB, et al, Incidence of keratitis of varying severity among contact lens wearers. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 2005. 89(4): p. 430-436.

- Allansmith, MR, et al, Giant papillary conjunctivitis in contact lens wearers. American journal of ophthalmology, 1977. 83(5): p. 697-708.

- Nichols, KK, et al, Corneal staining in hydrogel lens wearers. Optometry and vision science, 2002. 79(1): p. 20-30.

- Morgan, PB and N Efron, Global contact lens prescribing 2000-2020. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 2022. 105(3): p. 298-312.

- Morgan, PB and N Efron, Quarter of a century of contact lens prescribing trends in the United Kingdom (1996–2020). Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2022. 45(3): p. 101446.

- Efron, SE, et al, A theoretical model for comparing UK costs of contact lens replacement modalities. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 2012. 35(1): p. 28-34.

- Efron, N, et al, A ‘cost-per-wear’model based on contact lens replacement frequency. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 2010. 93(4): p. 253-260.

- Institute, Cl, Remarkable Resilience: Prescribing Contact Lenses in a Challenging Economy. 2022.

- Hashemi, H, et al, Global and regional estimates of prevalence of refractive errors: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of current ophthalmology, 2018. 30(1): p. 3-22.

- Pesudovs, K, E Garamendi, and DB Elliott, A quality of life comparison of people wearing spectacles or contact lenses or having undergone refractive surgery. Journal of Refractive Surgery, 2006. 22(1): p. 19-27.