Earlier this year, I wrote a short article entitled ‘Sins of Commission vs Sins of Omission’ regarding the rapidly emerging world of myopia management from my perspective as clinical consultant to the Optical Consumer Complaints Service (OCCS).1 In that piece, I outlined the competing risks associated with the transition of myopia management into mainstream optometry.

These might best be summarised as follows:

- Risks of commission: ‘I am disappointed with the result.’

- Risks of omission: ‘Why didn’t you tell me about this?’

Since writing that article, we still have not received a complaint at the OCCS in this area. I have, however, had the pleasure of travelling the length and breadth of the country delivering a CPD session titled ‘Great expectations’ to hundreds of clinicians.

The session uses redacted OCCS complaints from other areas of optometry, such as orthokeratology and refractive surgery, to challenge delegates in dealing with related complaints and to think about how this might be relevant to be successful in the practice of myopia management. I believe the limiting factor in our success will not be the technology or products, but our ability to have brilliant set-up conversations, to assure a well-informed understanding is articulated to a parent about what myopia management is and what it is not. And how to communicate adequately an understanding of emerging developments in products as part of an overall strategy, one which includes advice about outdoor activity and compliance with product wearing times.

The CPD sessions have been exceptional in the level of engagement, reflecting a genuine interest in the subject and raising some brilliant questions. One, in particular, worth some discussion has been: ‘Would I be negligent not to mention myopia management to myopic parents who present with strong family histories of myopia before I have even seen the child?’

Myopia Focus

I have observed much of the growing interest in the topic of myopic management as being fuelled by two substantive motivational drivers:

- ‘I understand how big this is or could be.’ This cannot be overstated. Professor Brien Holden and his team have predicted that over 50% of the global population will be myopic by 2050,2 and this increasing incidence and its impact upon visual impairment across the globe is further reflected in more recent papers.3, 4 Indeed, the current chair of the World Council of Optometry, Dr Kovin Naidoo, describes myopia as ‘our Covid’ and suggests that society will not judge us kindly if we fail to meet the challenge. I cannot argue with that.

- ‘I don’t want to be off the pace.’ As we understand more and more about myopia and the tidal wave of research and data in this area washes over us all, it is impossible not to realise the compulsion for us to immerse ourselves in this emerging data. This will be critical to fulfil our role in advising parents and children and also in implementing cogent strategies for managing myopic progression.

Will I Get Struck Off If…?

More generally, I have been delivering CPD sessions for seven years and a pervading fear of many audiences is expressed by the question, ‘Will I get struck off if…?’

This, sometimes irrational, fear often belies a lack of real understanding of both the medicolegal environment and regulatory context. Inevitably, this question has evolved in the more recent CPD sessions into such questions as ‘Will I get sued if it doesn’t work?’ or ‘What position does the GOC take?’

So, how do the worlds of myopia management and complaints/medicolegal and regulatory collide? I am not a lawyer, and nor would I profess to be an expert in regulatory law or a spokesperson for our regulator. I am also very aware that every case must stand or fall on its individual merits. That said, what I can do to help readers understand this landscape is draw on my previous experience as Director of Professional Services for a large eye care provider and my nine years at the OCCS to try to explain, and hopefully reassure, how the various systems and processes function; in simple terms.

My first observation, based on insights from the OCCS world, is that there is a relatively high propensity for parents to complain when an issue impacts their child. This is entirely understandable and appropriate, but we need to be cognisant that this underlying anxiety will drive concerns and complaints. We also need to be particularly sensitive when dealing with such concerns.

To help CPD delegates understand how any complaint can escalate beyond practice level, I often try to categorise such complaints as involving three independent, yet overlapping, pathways as represented in the figure 1 Venn diagram below:

- Consumer complaints; these are the remit of the OCCS

- Litigation; these would include complaints subject to civil law

- Regulatory; these would be when a registrant’s fitness to practise is called into question

Consumer complaints could involve any manner of concerns and, as such, are relatively common. Civil litigation, although regularly threatened, is relatively rare and regulatory complaints even more so. Of course, a complaint could have elements that fall in to any combination of the three areas rather like a Venn diagram.

We will now consider each of these categories of complaint in a little more detail.

Consumer-based Complaints

Consumer-based complaints are the remit of the OCCS, and this category covers the majority of escalated complaints in our profession. Discontent with a service or product is inevitable in a sector that performs about 22 million eye examinations a year. Complaints in this arena can be about any issue or concern relating to an interaction with a GOC registrant and mediation has a broad range of options to resolve the matter. Of course, mediation is voluntary, although registrants are expected to engage with the OCCS encapsulated in the 2016 GOC Practice Standards.

The Optical Consumer Complaints Service (OCCS) is an independent and free service for consumers (patients) of optical care and the professionals providing that care. The service is funded by the General Optical Council who regulate opticians, optometrists (formerly ophthalmic opticians), dispensing opticians and any practice which offers their services.

All optical and optometry practices should have their own internal procedure to deal with any complaints raised by consumers. Most concerns are normally resolved informally. When a complaint cannot be resolved, the OCCS offers an impartial facility to help obtain a satisfactory outcome. We understand that it is important this is done fairly and quickly. We are respectful of equality and diversity; anyone who makes a complaint and anyone against whom a complaint is made will be treated fairly, whatever their background or circumstances.

The mediation process attempts to resolve problems without taking sides, making judgments or giving legal advice. The OCCS will offer guidance, ensure good communication and help the parties reach an agreement. We will listen to the complaint and then investigate. We will then work with both the complainant and the optician involved to help reach a fair resolution. By exploring why someone is dissatisfied, and listening to both sides, we will support everyone involved to work towards a solution.

Importantly, the process is:

- Confidential

- Impartial

- Resolution-focused

The OCCS aims to settle complaints about opticians both efficiently and quickly. We will offer solutions rather than impose decisions. We work with consumers and opticians to reach a solution that both sides are happy with, whether that is an apology, remedial treatment, a refund or referral to another professional. We cannot award or recommend compensation. While mediation is voluntarily entered into, there is an obligation under the 2016 GOC Practice Standards that a registrant will engage with the OCCS when required to do so.

As well as a complete complaints mediation service, we can also give guidance to optical professionals on how to resolve a complaint and provide initial assistance to consumers who may not be confident or able to raise a complaint alone.

So, what complaints reach the OCCS? Both sins of commission and of omission could reasonably come our way, and we will try to navigate a path to an outcome that both parties can agree on. We cannot stop a consumer complaining, but we can be well-positioned to address a concern.

Minimising the risk of complaints concerning myopia management probably starts with a well-articulated and balanced outline of the clinical data, possibly supported by documents. We should also direct families to online resources for further reading. This should form the basis of a cogent and reasonable overview, one which allows parents to make an informed choice about, for example, whether to pursue a myopia management intervention.

Of course, we should always write down the advice given. What we must avoid is over-promising and we should check our understanding with parents and children. Be clear about what myopia management is and what it is not. This is a touch on the brakes, a slowing down; it is not myopia cessation or myopia eradication.

When commencing myopia management, a simple consent form, in addition to good record keeping, is a great way to ensure understanding and commitment by the parents to the process and, of course, we should combine any intervention with complementary advice, such as regarding increased outdoor activity as part of a holistic approach.

I am anticipating complaints from disappointed parents to be heading our way in the coming years, but I am confident that, by following the advice of professional bodies and the steps outlined above, it will be possible to address the concerns raised. Good record keeping will be the cornerstone of any defence, but also make sure you aim to navigate a route through the complaint with the goal of retaining the trust and loyalty of the family involved. To that end, I would suggest inviting a complainant in to discuss their concerns. Apologise that they have been disappointed and felt the need to complain; and remember, this is not an admission of wrongdoing.

Explain, without jargon, what you have done and how you believe the process has worked. The challenge here is to reassure that the process is working when the actual prescription is tangible and what might have been is, in the eyes of the complainant, hypothetical. Apps and tools will be valuable here for demonstrating the positive impact of the intervention to a sceptical complainer.

Use your judgement to take necessary steps to secure ongoing commitment to the process. How we do this is a complete CPD course in itself, but by keeping yourself appraised of rapid research and insights in myopia, having good records and a simple consent form, you will be positioning yourself well for any future challenge.

If you are concerned a case may escalate to a civil litigation matter then you must notify your insurer and follow their guidance.

Civil Litigation

All registrants fear ‘being sued’; but how likely is that and what are the consequences?

Firstly, we should try not to, as many do, conflate a medicolegal claim for damages or compensation with regulatory action. The two are distinctly separate pathways and a clinician would be well served to view them as such. Rather like differentiating between a motoring accident resulting in an insurance claim (most drivers will experience that in their lifetime) as distinct from an incident where the police intervene to ban someone from driving (very rare); the world of civil litigation and regulation do not always align.

This area is expertly covered in Steve Taylor’s excellent new book Regulation and UK Optometry.5 In summary, three conditions must be met for a legal claim to succeed:

- A duty of care is owed personally by the defendant to the plaintiff

- That duty of care was broken

- Harm has been suffered as a result of the breach of duty

It is not hard to see how the first test would exist between an eye care practitioner and a patient. For the second test, it is harder to prove the following; ‘the behaviour of the defendant was sufficiently careless as to make it reasonably foreseeable that some injury may result.’ In this regard, we are all held to the standard of a reasonably competent optometrist. We are not expected to be at the ‘gold standard’.

The third element means that it must be shown that damage has occurred. If no harm results, then no amount of carelessness can produce any liability. In order to win a case, the plaintiff must show that ‘on the balance of probability, but for the defendant’s fault, the injury complained of would not have occurred’.

If all three elements are proven, then a court would consider damages as a financial measure of the harm suffered. The court will attempt to ensure the injured party is maintained in the position that they would have been in had the harm not occurred.

This will be made up of:

- Compensation for pain and suffering resulting from the harm

- Effect on enjoyment of life

- Loss of earnings capacity and prospects

- Loss of benefits

- Future expenses including medical care

Scary as this seems, we must remember that our professional indemnity insurance covers such claims, in a way similar to our motor insurance. If you are ever concerned about potential litigation, you should contact your insurer (AOP or FODO and so on) and seek advice as early as possible. A plaintiff will likely face another entry barrier in civil matter; that of cost. Remember, legal action, even if successful, does not in and of itself impact your right to practice.

It is not hard to imagine a ‘sins of commission or omission’ emerging in the context of a threat of litigation. But a complainant must be committed to the cost they could incur in pursuing a legal case, be able to show we breached our duty of care and they must demonstrate tangible loss or damage. I anticipate the bigger claims will emerge from a ‘you never told me about myopia management’ perspective, and it is not hard to see how some of these claims would succeed if indeed we fail to mention the option.

I believe a failure to mention or record that you mentioned myopia management is an approach that could be increasingly difficult to defend in the future. Whether mum or dad ultimately decide to proceed with a myopia management intervention is ultimately their decision, but I think our failure to even make them aware of the option could be hard to defend in the future. As an evidence-based clinical profession, how can we ignore the data we are now seeing regarding the efficacy of the products?

Moreover, clinicians will increasingly need to be up to speed with rapidly emerging research that aids our understanding of how and when to intervene. It is becoming clear that the earlier we intervene the better, that compliance with wearing schedules is key, that full-time wear appears to be more effective than part-time wear in slowing myopic progression in young myopes; the list of emerging insights goes on.

Regulatory Complaints

In this regard, the GOC function is simply one of public protection and, as such, a finding of impairment must, on the balance of probability, be proven. It cannot mediate, it cannot award damages or compensation.

Again, Taylor sets out in detail the process by which a finding of impairment can be proven and how this has changed following a significant amendment to the Opticians Act in 2005.5

Broadly speaking, impairment can be found as a result of the following:

- Misconduct

- Deficient professional performance

- Conviction or caution for a criminal offence (variations in Scottish Law apply here)

- Adverse physical or mental health

- An Fitness to Practise (FtP) finding by another health regulator

It is worth noting that deficient professional performance would usually be based on a fair sample of work, although a single clinical incident, if sufficiently serious, could reach the threshold.

In securing a finding of impairment there are a number of stages through which an allegation must navigate. Following the introduction of Acceptance Criteria in 2019, complaints to the GOC are now triaged to establish at the outset if the substance of the claim appears likely to meet the set of Acceptance Criteria as set out by the GOC.6 In situations where risk to the public is high, the registrar can refer a matter directly to the FTP committee to consider an interim order.

The triage team may undertake some initial enquiries to establish sufficient facts to make a triage decision, as to whether to:

- Close a complaint

- Pass it over to the OCCS

- Formulate an allegation

Last year, for example, almost 20% of complaints into the GOC were triaged across to the OCCS.

If a complaint clears triage, then an allegation will be referred to two case examiners (one registrant and one lay person) who will be appointed to determine; ‘Is there a realistic prospect of establishing that the registrant’s fitness to practise is impaired to a degree that justifies action being taken against their registration?’

Unsurprisingly, this is called the Realistic Prospect test. It is not the role of the case examiners to determine impairment or make findings of fact, although they do have the power when closing a case to issue a warning. Beyond that, the investigating committee will consider a case only if the case examiners refer it to them or if the case examiners cannot reach a decision.

Should an allegation still stand at this point, then a FtP committee will be formed and a formal hearing will take place. The committee must determine the facts; for example, in a case of misconduct, was that found to be the case? And does that amount to impairment. For example, a finding of deficient performance may be found to be proven but, if the registrant can demonstrate insight remediation at their hearing, the panel may then make a determination that they no longer represent a risk to the public and impairment may well not be proven. In which case, no formal sanction will be handed down.

Is It Hard to Get Struck Off?

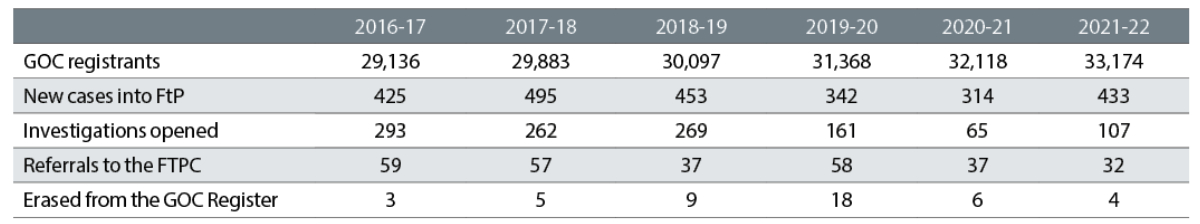

The recent changes to FtP processes have reduced unnecessary investigations, allowing the team to focus on the most concerning allegations and speeding up the FtP process. This is shown in the figures in table 1.

Table 1: Fitness to Practise interventions since 2016

For a myopia management complaint, one without any other influencing factors, to navigate all the way to the FTP Committee, I believe the ‘Sin of omission’ is where the greater risk lies. Being disappointed with the outcome, feeling oversold and so on should be manageable by a practitioner and the OCCS.

It is not hard to see how an allegation of failing to inform patients about myopia management options could reasonably get traction in FTP, for example if the records were inadequate or if the complaint was not a one-off and, instead, might be indicative of a recurring pattern of repeatedly failing to advise.

Complaint Avoidance

So, how do we avoid a complaint regarding myopia management from escalating into these three arenas, and how might we avoid it altogether?

On the first point; we cannot. By this, I mean that anyone can make a complaint about anything in any of these channels.

What is within our control, like any other element of optometric practice, is to make sure that we can defend any complaint as effectively as possible; do and say the right things and record this contemporaneously. Should you ever be unfortunate enough to receive notification of legal or regulatory action relating to myopia management (or any other matter), contact your representative body or professional indemnity insurer and work with them to address the concern.

Here are some top tips to help avoid complaints from escalating:

- Soak up CPD in this area to keep yourself appraised of the rapid developments in myopia management.

- Enable parents to make an informed choice. Develop your own phraseology toolkit to inform effectively.

- Record your advice and consider the use of a simple consent document.

Final Thoughts

Myopia management is one of the most exciting developments in eye care and has the potential to change billions of people’s lives for the better. Along with an enhanced role in managing chronic eye conditions, it has the potential to define our role in society over the coming decades. I think that ‘doing nothing’ will not be acceptable, either morally or professionally. We should be hugely excited about this opportunity and hugely measured in how we present the option to people.

I hope this article will help you put any concerns relating to myopia management complaints to the back of your mind; not entirely out of your mind, just not at the forefront.

- Richard Edwards is Clinical Consultant to the Optical Consumer Complaints Service.

References

- Edwards R. Myopia Management: The sins of commission versus the sins of omission. Optician, 05.05.2023, pp28-29

- Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology, 2016;123(5):1036–1042

- Fricke TR, Jong M, Naidoo KS, et al. Global prevalence of visual impairment associated with myopic macular degeneration and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050: Systematic review, meta-analysis and modelling. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 2018;102(7):855-862

- Sankaridurg P et al. IMI Impact of Myopia. Investigative Ophthalmology & Vision Science, 2021;62(5):2

- Taylor S. Regulation and UK Optometry. Stephen Taylor Associates, UK: Default Book Series, January 2023

- General Optical Council. Acceptance criteria. https://optical.org/media/pmchwj3d/acceptance-criteria.pdf