It is not uncommon for optometrists to come across children with visual dysfunctions that are not revealed as part of a standard eye examination. Although optometrists are not responsible for diagnosing visual processing dysfunctions, being able to recognise which children may require further investigation can be a turning point for patients and their families.

Children with cerebral visual impairment (CVI) from birth may not be aware that they have a visual impairment as they judge their vision to be normal. Parents may have sought advice when children’s behaviour caused concerns, but they often do not realise that the behavioural traits may have their origin in visual processing dysfunction, especially when their children’s routine sight test showed ‘normal vision’.

Indeed, it can be challenging for healthcare professionals to disentangle CVI from other disorders affecting behavioural, motor or cognitive disorders, and therefore, careful observation, history taking and assessment of visual functions are fundamental.

Diagnosis and management of CVI require a multidisciplinary approach, including medical professionals, educational professionals, the affected children and their carer-givers.1-3 There is currently no international consensus regarding the diagnosis and management of CVI.4 Depending on the treatment centre, a variety of diagnostic tests and questionnaires are used to aid diagnosis.1, 2

Pilling et al4 (2022) provide a practical guide for eye care professionals about detecting and diagnosing CVI, taking into account medical risk factors, structured history taking, assessment of visual behaviours, ocular examination, assessment of visual functions and visual perception, and symptoms of CVI.

This article provides an overview of commonly used assessments for the diagnosis of CVI.

Medical and birth history

Structured medical history taking is recommended, especially if parents are concerned about their child’s visual functioning.2 CVI can be a result of pre-natal, peri-natal and post-natal causes and therefore, medical and birth history are important when assessing children.5 Risk factors for CVI include premature birth/ low birth weight, infection, cerebral palsy, Down’s syndrome, hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy, hydrocephalus, epilepsy, traumatic brain injury, abnormal brain scans, developmental delay, genetic and metabolic disorders.1,2, 6-13

If a child presents with one of the above conditions, further assessment for potential CVI is warranted.

Ocular examination and visual function assessment

Ocular causes need to be ruled out before any visual difficulties can be assigned to neurological or neurodevelopmental causes5 and therefore, examination of ocular health and visual function are essential. The visual assessment includes careful observation of any visual behaviours suggestive of visual dysfunction from the time that the child is called from the waiting area and throughout the assessment.

Abnormal interaction, avoiding eye contact, overlooking things, difficulties with processing visual information, impaired recognition, motion perception, simultaneous perception, visual attention or visually guided reach are indications that a child may have CVI.4, 14

Vision assessment includes assessment of ocular motility and visual functions as certain visual dysfunctions are more commonly observed in children with CVI. Reduced visual acuity (especially crowded) and stereopsis, significant refractive error, reduced contrast sensitivity, nystagmus, visual field impairments, abnormal fixation, abnormal smooth pursuit and saccadic eye movements and strabismus are common in CVI.2, 6, 8, 15-19

In terms of ophthalmological findings, optic atrophy is associated with CVI and an OCT scan can aid in diagnosis.18, 20 Fundus and anterior segment examination are essential in order to rule out ocular pathology.

Neuro-imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appears to be the most suitable brain imaging technique to detect and localise brain damage in infants and children with suspected CVI.21 If abnormalities are detected on MRI, this could give more insight into the aetiology of visual dysfunction. Although a normal MRI scan does not exclude CVI as a diagnosis,3, 22-24 there is often a relationship between MRI findings and CVI in children with visual dysfunction.2,8,12,18,25,26 Neuro-imaging plays an important role in developing our understanding about the condition. However, it is often not necessary to perform neuro-imaging for primary investigation of CVI.27

Neuropsychological assessment

There is a number of assessment tools available to assess visual perception, which aid in building a clinical picture. However, Boonstra et al2 warn that neuropsychological tests have limited diagnostic accuracy for the assessment of CVI and recommend that they should not be used in isolation. Orbitus et al28 investigated how well neuropsychological tests correlate with information obtained through the use of a CVI questionnaire and they conclude that a CVI questionnaire is a viable tool as part of routine screening for CVI.

Structured history taking using CVI question inventories

History taking in the context of CVI serves two purposes: The primary goal of history-taking in the medical setting is focused on pathology, whereby the nature, aetiology and origin of the cerebral pathology is investigated. In the low vision setting or habilitational setting, the primary goal is a functional one, whereby the impact of the condition on everyday activities, learning, development and behaviour are assessed with a view to offer habilitation strategies.3 The latter will be discussed in more detail in a later article. Here, the focus is on diagnostic history-taking.

In order to characterise and address specific visual difficulties, question inventories are developed, which are based on patient-reported visual dysfunctions. Jackel et al29 showed that parents are often the first adults to suspect that there is something wrong with their children’s vision, which supports the notion that parent observations are an important element in the diagnosis of this condition.

Question inventories usually group the visual dysfunctions into different domains, such as visual attention, fixation and visual fields, visual recognition, movement perception, simultaneous perception, visually guided movement, ability to handle the complexity of a visual scene or a crowded environment and the use of other senses.28, 30

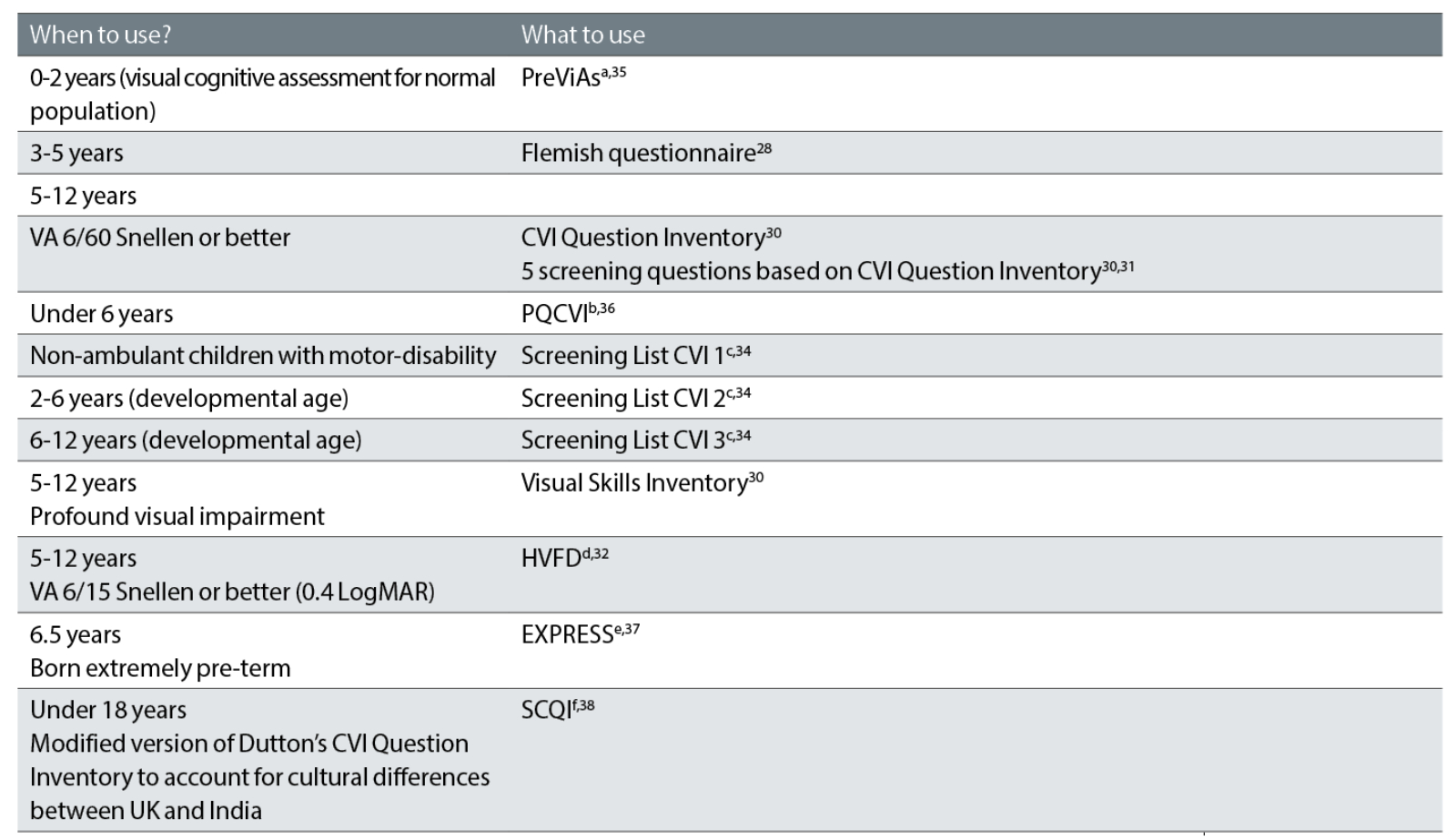

Depending on the developmental age of the child as well as the presence or absence of other disabilities, different question inventories may be used (see table 1). Dutton and Bax30 introduced a 22-item visual skills inventory for children with profound visual impairment (pp. 125-126) and a 52-item question inventory for children with suspected CVI and Snellen acuities of 6/60 or better (pp. 119-122). The latter has been validated, adapted and used as a screening tool.28,31-33

Table 1: Question Inventories for the identification of potential CVI

aPreViAs=Preverbal Visual Assessment, bPQCVI=Parental Questionnaire for Cerebral Visual Impairment, cNIBVID=The National Institute for the Blind, Visually Impaired and Deafblind, Iceland, dHVFD=Higher Visual Function Deficit, eEXPRESS= Extremely Preterm Infants in Sweden Study, fSCQI=Structured Clinical Question Inventory

In order to make the use of question inventories more accessible and to create a bridge between health care and educational professionals, different versions of the question inventory have been made available online by ‘Teach CVI’.34 Each one is used for a different sub-group of patients, depending on their ability to mobilise, and depending on their developmental age. The online screening tools are intended as a first step in identifying CVI to decide if a child needs onward referral for further assessment.

Pilling27 stresses the importance of assessing how a child sees, rather than what a child can see and recommends asking open questions about how the child uses their vision to walk, talk, read and feed. She also introduces the Visual Behaviour Matrix, which serves as a guide of typical visual development in the domains of awareness and attention (‘See it’), fixation and field (‘Find it’) and motor response (‘Use it’).

Summary

Diagnosis and assessment of CVI require a multidisciplinary approach, tailored to the child’s age, cognitive ability and co-morbidities. Conventional diagnostic tests may not always be possible and therefore, the clinician should be prepared to use alternative strategies to assess these children.

Observation of behaviour in the clinical setting and by the care-givers are essential to understand how the child uses their vision. Special consideration should be given to assessing children with complex neurodevelopmental conditions in order to elicit the evidence of visual processing dysfunction.

Recommendations for optometrists

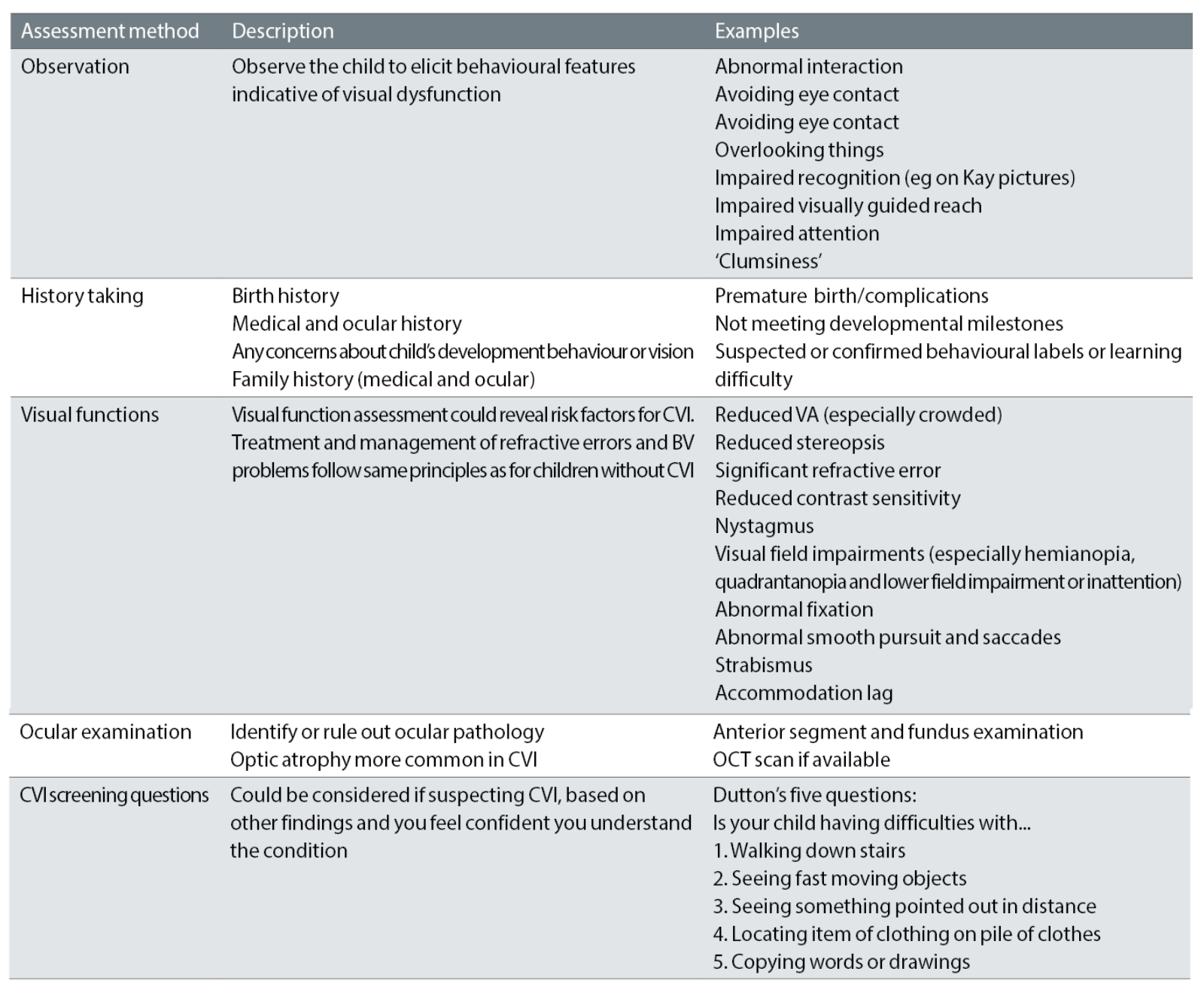

This article has outlined the investigations that are commonly used in the diagnosis of CVI. While optometrists are not expected to diagnose CVI, there are some take-home messages for optometrists as outlined in table 2. The key is for optometrists to familiarise themselves with this condition in order to be better equipped to identify children at risk when they attend their practice.

Table 2: Steps to aid identifying children at risk of CVI in an optometric practiceevaluation

- Cirta Tooth is a specialist low vision optometrist, working in both private practice and the hospital eye service.

Resources for further study

The author has produced an introductory video, which can be viewed here: youtu.be/3rA7kj8bVjQ

References

- McConnell, E. L., Saunders, K. J. and Little, J-A. 2020. What assessments are currently used to investigate and diagnose cerebral visual impairment (CVI) in children? A systematic review. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 41(2), pp. 224-244. doi:10.1111/opo.12776

- Boonstra, F., M., Bosch, D., G. M., Geldof, C., J., A., Stellingwerf, C. and Porro, G. 2022. The multidisciplinary guidelines for diagnosis and referral in cerebral visual impairment. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. doi:10.2289/fnhum.2022.727565

- Lueck, A., Dutton, G. and Chokron, S. 2019. Profiling children with cerebral visual impairment using multiple methods of assessment to aid in differential diagnosis. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology 31, pp. 5-14. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2019.05.003

- Pilling, R. F., Allen, L., Bowman, R., Ravenscroft, J., Saunders, K. J. and Williams, C. 2022. Clinical assessment, investigation, diagnosis and initial management of cerebral vsual impairment: a consensus practical guide. Eye. 36258009. doi:10.1038/s41433-022-02261-6

- Philip, S. S. and Dutton, G. N. 2014. Identifying and characterising cerebral visual impairment in children: a review. Clinical and Experimental Optometry 97, pp. 196-208. doi:10.1111/cxo.12155

- Fazzi, E. et al. 2008. Spectrum of visual disorders in children with cerebral visual impairment. Journal of Child Neurology 22(3), pp. 294-301. doi:10.1177/0883073807300525

- Kabakus, N., Yilmaz, T., Balci, T. A., Kamisli, O., Kamisli, S. and Yildirim, H. 2005. Cortical visual impairment secondary to hypoglycemia Neuro-Ophthalmology 29, pp. 27-31.

- Khetpal, V. and Donahue, S. P. 2007. Cortical visual impairment: etiology, associated findings, and prognosis in a tertiary care setting. Journal of Americal Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 11(3), pp. 235-239. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.01.122

- Yalnizoglu, D., Hliloglu, G., Turanli, G., Cila, A. and Topcu, M. 2007. Neurologic outcome in patients with MRI pattern typical for neonatal hyoglycemia. Brain and Development 29, pp. 285-292.

- Bosch, D. G. N. et al. 2016. Novel genetic causes for cerebral visual impairment. European Journal of Human Genetics 24, pp. 660-665.

- Jin, H. D. et al. 2019. Cortical visualimpairment in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 56(3). pp. 194-203. doi:10.3928/01913913-20190311-01

- Chang, M. Y. and Borchert, M. S. 2020. Advances in the evaluation and management of cortical/cerebral visual impairment in children. Survey of Ophthalmology 65(6), pp. 708-724.

- Hamilton, R., McGlone, L., MacKinnon, J. R., Russell, H. C., Bradnam, M. S. and Mactier, H. 2010. Ophthalmic, clinical and visual electrophysiological findings in children born to mothers prescribed substitute methadone in pregnancy. British Journal of Ophthalmology 94(6), pp. 696-700. doi:10.1136/bjo.2009.169284

- Zihl, J. and Dutton, G. N. 2015. Cerebral visual impairment in children. Wien: Springer-Verlag.

- Fazzi, E. et al. 2012. Neuro-ophthalmological disorders in cerebral palsy: ophthalmological, oculomotor, and visual aspect. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 54(8), pp. 730-736. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04324.x

- Jacobson, L. K. and Dutton, G. N. 2000. Periventricular leukomalacia: an important cause of visual and ocular motility dysfunction in children. Survey of Ophthalmology 45(1), pp. 1-13. doi:10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00134-x

- Mayer, D. L. Taylor, C. P. and Kran, B. S. 2020. A new contrast sensitivity test for pediatric patients: feasibility and inter-examiner reliability in ocular disorders and cerebral visual impairment. Translational Vision Science and Technology 9(9). 32879786. doi:10.1167/tvst.9.9.30

- Van Genderen, M., Dekker, M. Pilon, F. and Bals, I. 2012. Diagnosing cerebral visual impairment in children with good visual acuity. Strabismus 20(2), pp. 78-83. doi:10.3109/09273972.2012.680232

- Huo, R., Burden, S. K., Hoyt, C. S. and Good, W. V. 1999. Chronic cortical visual impairment in children: aetiology, prognosis, and associated neurological deficits. British Journal of Ophthalmology 83, pp. 670-675. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.6.670

- Jacobson, L., Lennartsson, F. and Nilsson, N. 2019. Ganglion cell topography indicates pre- or postnatal damage to the retrogeniculate visual system, predicts visual field function and may identify cerrebral visual impairment in children: a multiple case study. Neuro-Ophthalmology 43(6), pp. 363-370. doi:10.1080/01658107.2019.1583760

- Thukral, B. B. 2015. Problems and preferences in pediatric imaging. Indian Journal of Radiology and Imaging 25(4), pp. 359-364. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.169466

- Orbitus, E., Lagae, L., Casteels, I., Demaerel, P. and Stiers, P. 2009. Assessment of cerebral visual impairment with the L94 visual perceptual battery: clinical value and correlation with MRI findings. Develeopmental Medicine and Child Neurology 51(3), pp. 209-217. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03175.x

- Towsley, K., Shevell, M. I., Dagenais, L. and Repacq Consortium. 2011. Population-based study of neuroimaging findings in children with cerebral palsy. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology 15, pp. 29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2010.07.005

- Boot, F. H., Pel, J. J. M., van de Steen, J. and Evenhuis, H. M. 2010. Cerebral visual impairment: Which perceptive visual dysfunctions can be expected in children with brain damage? A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities 31, pp. 1149-1159. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.08.001

- Philip, S. S., Guzzetta, A., Chorna, O., Gole, G., and Boyd, R. N. 2020. Relationship between brain structure and cerebral visual impairment in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Research in Developmentla Disabilities 99, 103580. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103580

- Tinelli, F., Guzzetta, A., Purpura, G., Pasquariello, R., Cioni, G. and Fiori, S. 2020. Structural brain damage and visual disorders in children with cerebral palsy due to periventricular leukomalacia. NeuroImage: Clinical 28. 102430. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102430

- Pilling, R. F. (no date). Make It Easier to See: How can we assess a child for CVI? Available at: https://makeiteasiertosee.co.uk/how-can-we-diagnose-cvi/ [Accessed: 19 January 2023].

- Orbitus, E. et al. 2011. Screening for cerebral visual impairment: value of a CVI questionnaire. Neuropediatrics 42(4), pp. 138-147. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1285908

- Jackel, B., Wilson, M. and Hartmann, E. 2010. A survey of parents of children with cortical or cerebral visual impairment. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness 104(10). doi: 10.1177/0145482X1010401007

- Dutton, G. N. and Bax, M. 2010. Visual Impairment in children due to damage to the brain. London: Mac Keith Press.

- Gorrie, F., Goodall, K., Rush, R. and Ravenscroft, J. 2019. Towards population screening for Cerebral Visual Impairment: Validity of the Five Questions and the CVI Questionnaire. Plos One 14(3). e0214290. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0214290

- Chandna, A., Ghahghaei, S., Foster, S. and Kumar, R. 2021. Higher visual function deficits in children with cerebral visual impairment and good visual acuity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 15. Article number 711873, pp.1-14.

- Macintyre-Béon, C., Young, D., Calvert, J., Ibrahim, H., Dutton, G. N. and Bowman, R. 2012. Case Report. Eye 26, p. 1393. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.154

- NIBVID (The National Institute for the Blind, Visually Impaired and Deafblind, Iceland). 2015. Teach CVI. Available at: https://www.teachcvi.net/ [Accessed: 29 January 2023].

- Pueyo, V. et al. 2014. Development of the Preverbal Visual Assessment (PreViAs) questionnaire. Early Human Development 90, pp. 165-168. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.01.012

- Moon, J-H. et al. 2021. Development of the parental questionnaire for cerebral visual impairment in children younger than 72 months. Journal of Clinical Neurology 17(3), pp. 354-362. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2021,17.3.354

- Hellgren, K., Jacobson, L., Frumento, P., Bolk, J., Ådén, U., Libertus, M. E. and Benassi, M. 2020. Cerebral visual impairment captured with a structured history inventory in extremely preterm born children aged 6.5 years. Journal of the American Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 24(1). e 1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2019.11.011

- Philip, S. S., Tsherlinga, S., Thomas, M. M., Dutton, G. N. and Bowman, R. 2016. A validation of an examination protocol for cerebral visual impairment among children in a clinical population in India. Journal for Clinical and Diagnistic Research 10(12). doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/22222.8943