The first article in this series focused on the epidemiology, diagnosis, referral and treatment update of retinoblastoma (Rb). This second and final article in the series considers the psychological and social impact of being diagnosed with and treated for the condition.

Although understanding of the biological components are well understood, little is known about the psychological impact of being diagnosed with and treated for Rb.1-3 For this reason, existing research has highlighted the need for specific psychosocial support for this group.1,4,5

To my knowledge at the time of writing, there are no routine psychological support interventions designed to be offered to young survivors at any age or stage of their development.6 It is important that all professionals involved in Rb care are knowledgeable about the potential impact on wellbeing, as well as how to provide support to mitigate this.

This article focuses on our recent findings regarding the psychosocial challenges faced by teenagers and young adults. It also provides recommendations for supportive interventions and considers how ophthalmic professionals can utilise our findings in their consultations.

Introduction to child and young adult survivorship

With the vast majority of cases of Rb developing in the first few years of a child’s life, treatment involves radiotherapy, chemotherapy, local ophthalmic therapies and sometimes enucleation.5,7 Although highly successful, many factors including these treatments, the cancer itself, and genetic components, can leave individuals with reduced vision, facial changes and identity-related distress.8,9

It is widely documented that the impact of any cancer and/or treatment can have both long and short-term effects on psychosocial wellbeing, some of which can last throughout a lifetime.10,11 For those impacted by Rb this can be even greater. The genetic form of Rb poses numerous additional challenges for individuals, who may pass on the gene to any future children and who are at greater risk of developing second primary cancers, which is understandably associated with increased anxiety and distress.2

Psychological and social needs across the lifespan

Rb is unusual as most cases are diagnosed and treated before a child is five years old.12 This has the potential to distort memories and complicate psychosocial outcomes as young people grow up.13 For this reason, much research has historically focused on the experiences of parents,14,15 wrongly assuming that infants will not be able to recall any diagnosis or treatment due to their young age.

Recent research suggests that this is not the case, and although childhood cancer experiences in infancy are unlikely to be recalled explicitly, memories are constructed through parents’ reactions, the emotions experienced and physical pain.16,17

Because of this historical assumption that young survivors do not remember their experiences, there are limited studies which specifically focus on the psychological impact of Rb on the diagnosed child themselves. Of the few Rb-specific studies available, findings are similar to those in the general cancer population, with children experiencing a range of negative psychosocial outcomes. These include the broader anger, anxiety and sadness experienced by many cancer diagnoses, but further explicit distress if an individual has lost an eye(s) through Rb.18,19

It is also recognised that young people who have experienced cancer are at heightened risk of identity distress.20 This concept describes concerns around how the self is perceived in terms of psychosocial development, independence, appearance, social relationships and stigma, both now and in the future.21 The likelihood of distress is raised when there have been associated changes in physical appearance due to illness and/or treatment, as for many individuals who have had Rb.10,22,23

There is extensive evidence to suggest that psychosocial support is warranted, and wanted, in the Rb population. Recent qualitative studies have found that both teenagers and young adults would like access to psychologists who have specialist knowledge of Rb-related challenges, preferably offering psychoeducation at early stages to prevent potential Rb-related psychological difficulties.1,2, 24, 25

Despite this, the explicit content of such challenges needs in-depth exploration, with particular consideration of how psychological and social needs change across the lifespan. With many concerns becoming apparent after an individual is discharged from their Rb specialist team, opticians and routine eye health check appointments have a key role in supporting the wellbeing of Rb survivors.

Identity-related distress

A diagnosis of cancer can be profoundly challenging at any age, often promoting questions about ones’ sense of self and the world around us. Childhood is a time of identity construction, so when cancer is a part of the developmental experience it can lead to high levels of identity-related distress.17 Survivors of Rb in particular may experience feelings of isolation, and a struggle to comprehend their reality as they grow older.

This emotional challenge can be intensified by societal expectations and pressures to be ‘normal’ once in remission, with many failing to acknowledge the impact on development that cancer can have on both the survivor and their family. Managing the complexities of survivorship while growing older can be an ongoing challenge, which requires compassionate support and understanding from family, friends and professionals alike.

With many children being discharged from their Rb teams while still relatively young, opticians and ophthalmologists are key in offering this process, often being the professional group who checks in with survivors most frequently.

Memories from treatment

As Rb is most often diagnosed in babies and young children, many Rb survivors discuss the expectation from others, and to some extent the reality, of not having fully formed memories of diagnosis and treatment. Pre-verbal memories in childhood are hard to convey, as they are experienced before a child develops the ability to communicate through verbal language.26

For young children, memories are believed to be stored in alternative formats, including sensorily, emotionally and visually. Much research into trauma and recollection of traumatic memories supports this idea.27 For survivors of Rb, it is likely that they will have undergone numerous Examinations Under Anaesthetic (EUA), as well as numerous other medical procedures and hospital visits; this must be considered when supporting Rb survivors to manage their long-term ocular health.

Although memories from Rb diagnosis and treatment are unlikely to be recalled by survivors in full and conscious detail, they can still have influence on an individuals’ behaviour, emotional responses and mental wellbeing. Gaining further understanding into this experience, as outlined in my recent research below, is crucial in supporting Rb survivors through adolescence and into adulthood.

An insight into the psychological and social impact on Rb survivors

To understand the specific views of teenagers and young adults further, my research team and I conducted a qualitative study utilising focus groups with teenagers and young adults (aged 13-29 years). Thirty-two young people took part who had diverse experiences including any form of Rb (heritable or non-heritable), bilateral or unilateral, diagnosed at any age, and having undergone any treatment regime.

The themes of individuals’ experiences were vast, with much of the discussions thinking back to childhood and remembering treatment and the impact on the family unit, adolescence and how having had Rb impacts your identity, adulthood and the lasting psychosocial impact of Rb in the present. These narratives were present across teenage and young adult participants, with it widely acknowledged that coping with Rb is most difficult during the adolescent years and are summarised below.

Childhood

Traumatic experiences

One potential impact arising from Rb diagnosis was life-long trauma. Variations of this legacy appear to be influenced by the age a child is diagnosed, the genetic nature of the diagnosis, wider family history of the condition, the severity of visual and facial impact, and late affects from the treatment received.

Many young people spoke about feeling ‘survivor guilt’ and the impact of this on their family, acknowledging empathy for their parents and the decisions that they had to make regarding treatment. This had a subsequent wider impact on their own behaviour and feeling unable to talk to their parents about how they feel. This links to the need for young people to access information and support independently at an age, and developmentally appropriate time, in a way that is autonomous from parents and family members. It may be that optician appointments are one such way that individuals can access information, as discussed later in this article. (Image courtesy of Robyn Giddings and Amber Davies)

they had to make regarding treatment. This had a subsequent wider impact on their own behaviour and feeling unable to talk to their parents about how they feel. This links to the need for young people to access information and support independently at an age, and developmentally appropriate time, in a way that is autonomous from parents and family members. It may be that optician appointments are one such way that individuals can access information, as discussed later in this article. (Image courtesy of Robyn Giddings and Amber Davies)

Memories from treatment

Although many of the individuals in this sample received treatment while very young, key, often sensory memories, could be recalled vividly in adolescence and young adulthood. For some these memories were more dormant, being triggered by external sensory experiences, notably smells. It is therefore important for all healthcare professionals to be mindful of the potential triggers that clinical appointments might have, including the smells of antibacterial gels and the sensations associated with having routine eye examinations.

Adolescence

Psychological impact

Ironically, it was widely discussed that adolescence was the time when individuals felt most unable to articulate their thoughts and to ask for or accept help. At the time when help was universally felt to be most needed, it was equally the most difficult time to acquire support. This suggests that the time before transitioning to secondary school might be the most useful to receive a targeted psychological intervention, offering coping strategies before they are needed and at an age where support could be more easily accepted. In addition, it may be that opticians can act as a key support throughout the lifetime, offering more ad hoc support at routine eye examinations in adolescence and beyond.

Ironically, it was widely discussed that adolescence was the time when individuals felt most unable to articulate their thoughts and to ask for or accept help. At the time when help was universally felt to be most needed, it was equally the most difficult time to acquire support. This suggests that the time before transitioning to secondary school might be the most useful to receive a targeted psychological intervention, offering coping strategies before they are needed and at an age where support could be more easily accepted. In addition, it may be that opticians can act as a key support throughout the lifetime, offering more ad hoc support at routine eye examinations in adolescence and beyond.

Case Example

A young adult with a history of unilateral Rb treated with enucleation described an experience where her optician was not aware of her medical history. She explained that she felt embarrassed at having to repeat this information multiple times after she was asked to complete a sight test out of her prosthetic eye. This highlights the importance of all professionals being aware of Rb and the treatments offered, including the long-term effects of enucleation and prosthetic use.

‘He tried to test my left eye and cover my right eye after telling him, “I’ve only got one eye,” and he didn’t listen, so I put in a massive complaint because he wasn’t listening after telling him about six times, “You don’t need to test my left eye; I can’t read the letters out of my left eye.”’

Identity

As you might expect of adolescence, identity was a key theme and for many there was a recognition that they had numerous questions about themselves, and how their history of having had Rb impacted their sense of self. Individuals who were still teenagers at the time of interview expressed frustration that others around them made Rb a core feature of their identity, when they were often trying to hide this. This suggests that a level of acceptance of what has happened to you comes with age and accessing psychological support, again highlighting the potential for opticians to offer support in their consultations throughout the lifespan.

Adulthood

Acceptance

Acceptance is a state of being that was universally considered to be unachievable while still young. Reasons why include a lack of choice, being unable to validate yourself, and not having access to others who are like you. In comparison to their teenage years, many young adults had developed the ability to accept themselves and their identity, acknowledging the experience of Rb without making it the only thing about them. Professionals who provide a space to ask questions and have open conversations about Rb were widely regarded as helpful.

Case Example

A teenager with a history of unilateral Rb treated with cryotherapy and chemotherapy described how important it was to have open dialogue with health care professionals, with her optician creating a safe space to discuss any worries she had about having had Rb.

‘I’ve got a quite close relationship with like my opticians, my doctors, my nurses.’

Coping strategies and support

Young adults had learnt coping strategies to manage the psychosocial impact of Rb. This included the need to seek out information to develop personal understanding.

There was a huge focus on the need for education for the young person in addition to their parents. Of course, in childhood cancers like Rb, it is often parents who are given the information and education at the time of diagnosis and treatment. Although there is now a greater push from the NHS for young people to take ownership of their health at long-term follow-up clinics, many of this sample felt that it was hard to know what you needed to know, what and who to ask for advice. We encourage all professionals to provide an opportunity to ask questions in their consultations and suggest strategies on how best to support this below.

How Opticians can help

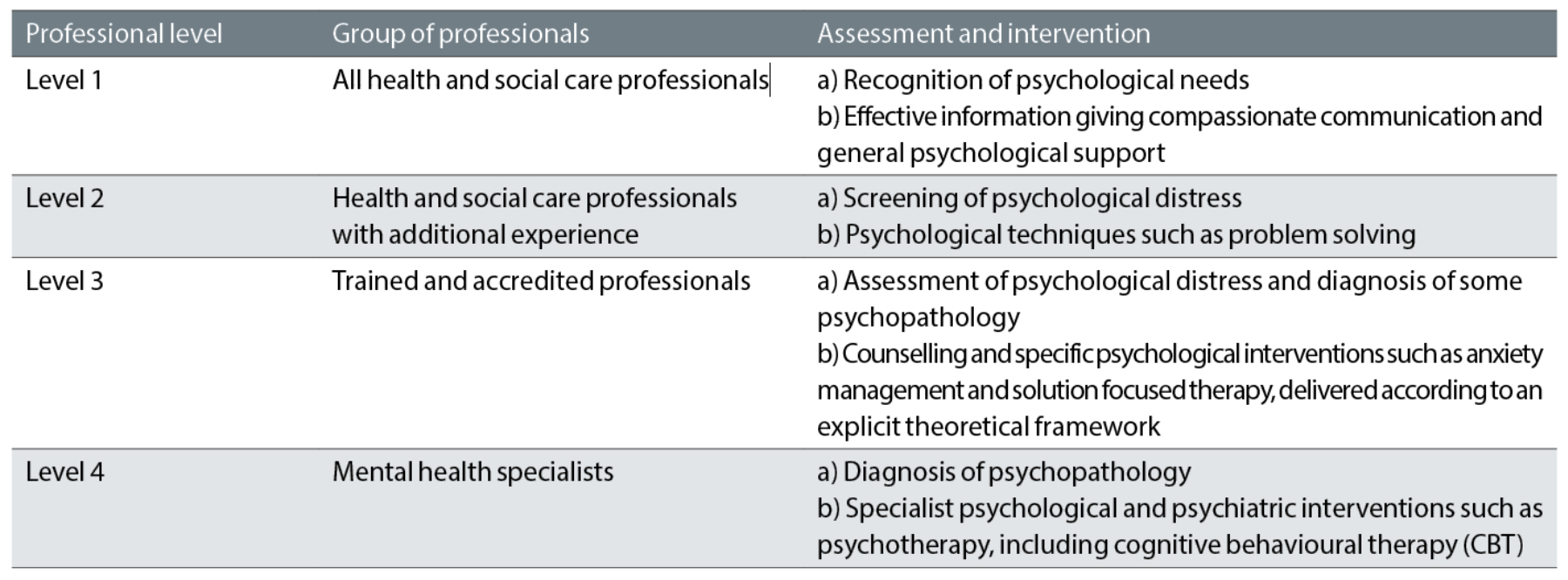

Although not their primary role, opticians and ophthalmic professions play a crucial role in providing psychological support to survivors of conditions like Rb. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has proposed guidance about the provision of supportive care for adults with cancer.28 This model states that all health and social care professionals have a role to play in supporting the wellbeing of individuals who have or have survived cancer (see table 1).

Table 1: NICE model of professional psychological assessment and support28

Psychological support can be provided by all professionals, regardless of whether they are specifically trained in mental health. Broadly speaking, the professional levels are divided into those trained specifically in mental health (levels 3 and 4) and those who are not (levels 1 and 2), with opticians and ophthalmologists typically falling into level 2 of NICE’s model. This means that they are well placed to observe symptoms of psychological distress and offer brief intervention and/or signposting.

After being discharged from specialist care, it is likely that visits to the optician will be the most regular contact an individual has with professionals who have specific understanding of Rb. These relatively regular routine appointments can provide the ideal opportunity for young people to discuss any concerns related to their vision or eye health, as well as the impact of this on their mental health and wellbeing.

Through providing an open and curious dialogue, opticians can create a safe space for survivors to express difficult thoughts and feelings. They are ideally skilled to provide information and education, answer any questions, and to offer reassurance and empowerment in managing their ongoing eye health.

By being aware of the potential psychological impact of Rb, opticians can be alert to signs of emotional distress or concern during these appointments, signposting to more specialist sources of support if required. Sometimes all that is required is a quick check in or a listening ear, highlighting the power of a brief appointment on improving Rb survivors’ psychological wellbeing and quality of life.

Case Example

A teenager with a history of unilateral Rb treated with cryotherapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and laser discussed how meaningful it was that his opticians checked in with him and provided a space to discuss any concerns. He described how it was rare to have the opportunity to speak to other healthcare professionals who understood the impact of Rb, making it even more valuable to have time with an optician who is well placed to provide this support.

‘At my check-ups… every time they ask me how I’m doing, like, if anything’s wrong, even at the opticians they ask me, so that’s really good.’

Understanding the specific needs and challenges for individuals living beyond Rb is essential to providing supportive optical care. This includes being aware of the history of the individual, including whether they have been treated with enucleation, or indeed interventions such as radiotherapy, as these can have long-term impact on vision and eye health.

Offering personalised, Rb-specific follow-up care ensures that the unique requirements of Rb survivors are managed effectively, offering a holistic assessment of their needs and contributing to multi-disciplinary support.

Case Example

A young adult with a history of bilateral Rb treated with cryotherapy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, described how important opticians are in validating difficult feelings. She described an experience where an optician had not encountered Rb in clinical practice, and therefore did not feel able to have a conversation with her about the impact of this on both her sight but also her sense of self.

‘Sometimes it is good to speak to people that are specialists, because it is quite, you know, a rare condition. And even when you go to the opticians and you say about it, they’re like, “I’ve never heard of that,” or, “Oh, I’ve never seen anyone with that”, so you go, “Oh great,” ’cos when they do the eye test and there’s just nothing there, they’re like, “What?”’

Motivational interviewing

Psychological symptoms are often misunderstood, with low detection of distress at routine healthcare appointments.29 If individuals do not have a space to voice their concerns, they are more likely to develop long-term anxiety and depression and become dissatisfied with their care. Utilising a form of psychological support called ‘motivational interviewing’ can help opticians to detect such concerns during their appointments.

This ensures that they can offer appropriate holistic support while maintaining good patient-professional relationships that encourage survivors to engage in eye health check-ups.30,31 This approach can be integrated into routine appointments and is time-efficient, respecting that optician’s primary role is to consider eye health.

To guide a conversation with Rb survivors, the ‘elicit-provide-elicit’ model can be drawn upon. Firstly, opticians can elicit information from the individual; what do they already know about Rb? What do they want to know (if anything)?

Second, provide targeted information to bridge gaps in understanding. Lastly, elicit what the survivor is making of this information; what do they take from what you have said? Do they understand? What do they want to do with this information now? This approach has been shown to be an effective way of healthcare professionals supporting their patients, providing learning opportunities to fill the knowledge gap that survivors commonly have, as highlighted in our Rb study.

Signposting

Should opticians become aware that a patient is struggling with their mental health or wellbeing, signposting to more specialist services (levels 3 and 4) is advised. The following services are recommended as key resources for opticians, providing Rb survivors with specific support that they can access as and when necessary:

- Childhood Eye Cancer Trust (CHECT): support@chect.org.uk, 0207 3775578

- Young Minds (for teenagers): text line, text ‘YM’ to 85258 for free 24/7 support

- Shout (for adults): text line, text ‘SHOUT’ to 85258 for free 24/7 support

- NHS psychological therapies (IAPT): nhs.uk/service-search/mental-health/find-a-psychological-therapies-service/ , self-refer for free talking therapies (18+)

- IAM (Teenage Cancer Trust): emotional and clinical support tool for young people who’ve had cancer, teenagecancertrust.org/help-and-support/apps-and-tools/iam-emotional-and-clinical-support-tool

Conclusion

The psychosocial impact of having Rb can be long lasting; the influence of having had childhood cancer, in some cases impacting the way you look, but often impacting the way you consider yourself and the world around you, can be devastating. For those with the hereditary form of the condition, these concerns can be even greater, often considering the impact of your behaviour and life choices on your future self, others and any future children. For those with prosthetics, the influence of others, especially if negative, can be hugely detrimental and affect peer and romantic relationships, and sense of identity.

Existing research has highlighted the need for psychosocial support, and it is hoped that evidence from the current study can be used to change the way that young people with Rb are supported psychologically, eventually leading to the development of an intervention that can be implemented into routine clinical practice.

For opticians and other professionals providing routine care, the opportunity to make a difference, even by modifying the format of a consultation, is vast. We hope that the overview provided in this article emphasises just how important opticians are in supporting the psychological wellbeing of Rb survivors, and provides information and guidance on how best to do this.

- Nicola O’Donnell is a final year PhD student and trainee health psychologist at the University of York. She is supervised by Dr Bob Phillips, Dr Debra Howell, and Dr Jess Morgan. Her research is funded by the Childhood Eye Cancer Trust (CHECT).

References

- Belson PJ, Eastwood JA, Brecht ML, Hays RD, Pike NA. A Review of Literature on Health-Related Quality of Life of Retinoblastoma Survivors. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2020;37(2):116-127. doi:10.1177/1043454219888805

- Gregersen PA, Funding M, Alsner J, et al. Living with heritable retinoblastoma and the perceived role of regular follow-up at a retinoblastoma survivorship clinic: € That is exactly what i have been missing’. BMJ Open Ophthalmology. 2021;6(1). doi:10.1136/bmjophth-2021-000760

- Fabian ID, Shah V, Kapelushnik N, et al. Examinations under anaesthesia as a measure of disease burden in unilateral retinoblastoma: The London experience. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020;104(1):17-21. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313556

- Feng Y, Zhou C, Jia R, Wang Y, Fan X. Quality of Life (QoL) and Psychosocial Outcomes in Adult Survivors of Unilateral Retinoblastoma (RB) in China. Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020;2020. doi:10.1155/2020/4384251

- Gündüz AK, Mirzayev I, Temel E, et al. A 20-year audit of retinoblastoma treatment outcomes. Eye (Basingstoke). 2020;34(10):1916-1924. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-0898-9

- Morse M, Parris K, Qaddoumi I, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and quality of life among school-age survivors of retinoblastoma. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2023;70(2):1-8. doi:10.1002/pbc.29983

- Balasopoulou A, Kokkinos P, Pagoulatos D, et al. Symposium Recent advances and challenges in the management of retinoblastoma Globe ‑ saving Treatments. BMC Ophthalmology. 2017;17(1):1. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO

- Sethi R V, Shih HA, Yeap BY, et al. Second nonocular tumors among survivors of retinoblastoma treated with contemporary photon and proton radiotherapy. Cancer. 2014;120(1): 126-133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28387

- Temming P, Arendt M, Viehmann A, et al. Incidence of second cancers after radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy in heritable retinoblastoma survivors: A report from the German reference center. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2017;64(1):71-80. doi:10.1002/pbc.26193

- Zebrack BJ. Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(SUPPL. 10):2289-2294. doi:10.1002/cncr.26056

- Bradley Eilertsen ME, Jozefiak T, Rannestad T, Indredavik MS, Vik T. Quality of life in children and adolescents surviving cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2012;16(2):185-193. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2011.08.001

- Roy SR, Kaliki S. Retinoblastoma: A Major Review. Mymensingh medical journal: MMJ. 2021;30(3):881-895. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34226484

- Wizansky B, Bar Sadeh E. Dyadic EMDR: A Clinical Model for the Treatment of Preverbal Medical Trauma. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy. 2021;20(3):260-276. doi:10.1080/15289168.2021.1940661

- Maryam D, Wu LM, Su YC, Hsu MT, Harianto S. The journey of embracing life: Mothers’ perspectives of living with their children with retinoblastoma. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2022;66:e46-e53. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2022.06.004

- Hamama-Raz Y, Rot I, Buchbinder E. The coping experience of parents of a child with retinoblastoma-malignant eye cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2012;30(1):21-40. doi:10.1080/07347332.2011.633977

- Hinton T, Burns-Nader S, Casper D, Burton W. Memories of adult survivors of childhood cancer: Diagnosis, coping, and long-term influence of cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2022;40(5):652-665. doi:10.1080/07347332.2022.2032530

- Tutelman PR, Heathcote LC. Fear of cancer recurrence in childhood cancer survivors: A developmental perspective from infancy to young adulthood. Psycho-Oncology. 2020;29(11):1959-1967. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5576

- Ek U. Emotional reactions in parents and children after diagnosis and treatment of a malignant tumour in the eye. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2000;26(5):415-428. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2214.2000.00159.x

- Beddard N, McGeechan GJ, Taylor J, Swainston K. Childhood eye cancer from a parental perspective: The lived experience of parents with children who have had retinoblastoma. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2020;29(2):e13209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13209

- Cook JL, Russell K, Long A, Phipps S. Centrality of the childhood cancer experience and its relation to post-traumatic stress and growth. Psycho-Oncology. 2021;30(4):564-570. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5603

- Barbot B, Piering K, Horcher D, Baudoux L. Creative recovery: Narrative creativity mitigates identity distress among young adults with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2021;0(0):1-15. doi:10.1080/07347332.2021.1907498

- Kearney JA, Ford JS. Adapting meaning-centered psychotherapy for adolescents and young adults with cancer: Issues of meaning and identity. In: Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy in the Cancer Setting: Finding Meaning and Hope in the Face of Suffering. Oxford University Press; 2017:100-111.

- Pearce S, Whelan J, Kelly D, Gibson F. Renegotiation of identity in young adults with cancer: A longitudinal narrative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020;102. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103465

- Banerjee SC, Pottenger E, Petriccione M, et al. Impact of enucleation on adult retinoblastoma survivors’ quality of life: A qualitative study of survivors’ perspectives. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2020;18(3):322-331. doi:DOI: 10.1017/S1478951519000920

- Gregersen PA, Funding M, Alsner J, et al. Danish heritable retinoblastoma survivors’ perspectives on reproductive choices: “It’s important for me, not to pass on this condition.” Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2023;32(1):31-42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1618

- Våpenstad EV, Bakkenget B. Pre-verbal Children’s Participation in a New Key. How Intersubjectivity Can Contribute to Understanding and Implementation of Child Rights in Early Childhood. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12(August):1-12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.668015

- De Luna JE, Wang DC. Child traumatic stress and the sacred: Neurobiologically informed interventions for therapists and parents. Religions. 2021;12(3):1-15. doi:10.3390/rel12030163

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Psychological Support Services.; 2004.

- Werner A, Stenner C, Schüz J. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting: how accurate is the detection of distress in the oncologic after-care? Psycho-oncology. 2012;21(8):818-826. doi:10.1002/pon.1975

- Seven M, Reid A, Abban S, Madziar C, Faro JM. Motivational interviewing interventions aiming to improve health behaviors among cancer survivors: a systematic scoping review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2023;17(3):795-804. doi:10.1007/s11764-022-01253-5

- Magill M, Hallgren KA. Mechanisms of behavior change in motivational interviewing: do we understand how MI works? Current Opinion in Psychology. 2019;30:1-5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.010