One of the absolute truths about life in optometry is that one day you will face a patient who is struggling to manage their newly prescribed spectacles. You will no doubt have taken care over a precise refraction, taken a good history and thought hard about what to prescribe.

There are numerous articles written in the optical press about how to minimise the non-tolerance, after all, it is not a comfortable place to be in professionally or in relationship with a client when the spectacles are deemed a ‘failure’ or when that ‘failure’ appears to be passed on to the dispensing optician or the optometrist. It undermines trust and is often expensive.

In this article I am going to tell a story that, on the surface, may be familiar to us all. This is varifocal non-tolerance and the actions of a quick-thinking dispensing optician. Studies have shown that varifocal non-tolerance is commonplace and, usually, can mostly be mitigated with precision measurements and care at dispensing and management of patient expectations.1 How often though do we look for a clinical cause?

This clinical example, (based on a real-life episode), demonstrates why it really matters to have a fully trained team around you in practice and to always approach each problem with a fresh outlook.

Case scenario:

Male patient, 67 years old, semi-retired, a habitual and happy varifocal wearer and a loyal customer. Presented for a sight test in late June (pre Covid-19 outbreak).

Hobbies include singing in a choir, golf, reading and supporting literacy at a local primary school.

Family history of maternal primary open angle glaucoma and cataract.

No medical history of note and no medications. Drives long distances to visit his family in Wales.

Current spectacles 12 months old;

RE +0.25/-0.75 x 15 6/18 ph 6/7.5

LE +1.00/-0.75 x 15 6/9 ph 6/7.5

Binocularly he sees 6/9-

Historically, this patient has been a low hyperopic astigmat. Over the past four years, his incipient lens opacities have caused an index myopic shift – more pronounced in the right eye. Although the corrected binocular visual acuity is good, the anisometropia was increasing and would be difficult to manage in a varifocal and keep comfortable vision.2

Primary presenting symptom was of glare and polyopia at night when driving home from choir practice and also blurry vision in the right eye for distance. He was noticing that this was especially noticeable on the golf course. He remembers his mum had cataract extractions before she was 70 years old.

Eye examination – further monocular index myopic shift. No oculomotor issues, threshold Sita Fast 24-2 fields full, digital widefield volk and laser scanning retinal imaging all normal. Pressures 16mmHg both eyes.

Rx on referral: (June)

R 6/12 -0.75/-0.75 x 15 6/6 ph 6/7.5

L 6/9 +0.75/-1.00 x 15 6/7.5 ph 6/7.5

The patient was referred routinely for cataract extraction based on the anisometropia, glare and polyopia. He elected to be seen privately as he had private health insurance. The consultant saw him within two weeks and listed him for simultaneous cataract extraction two weeks apart beginning in mid-August. The patient was flying long distance in the autumn and wished to have ceased his post-operative drops by this time.

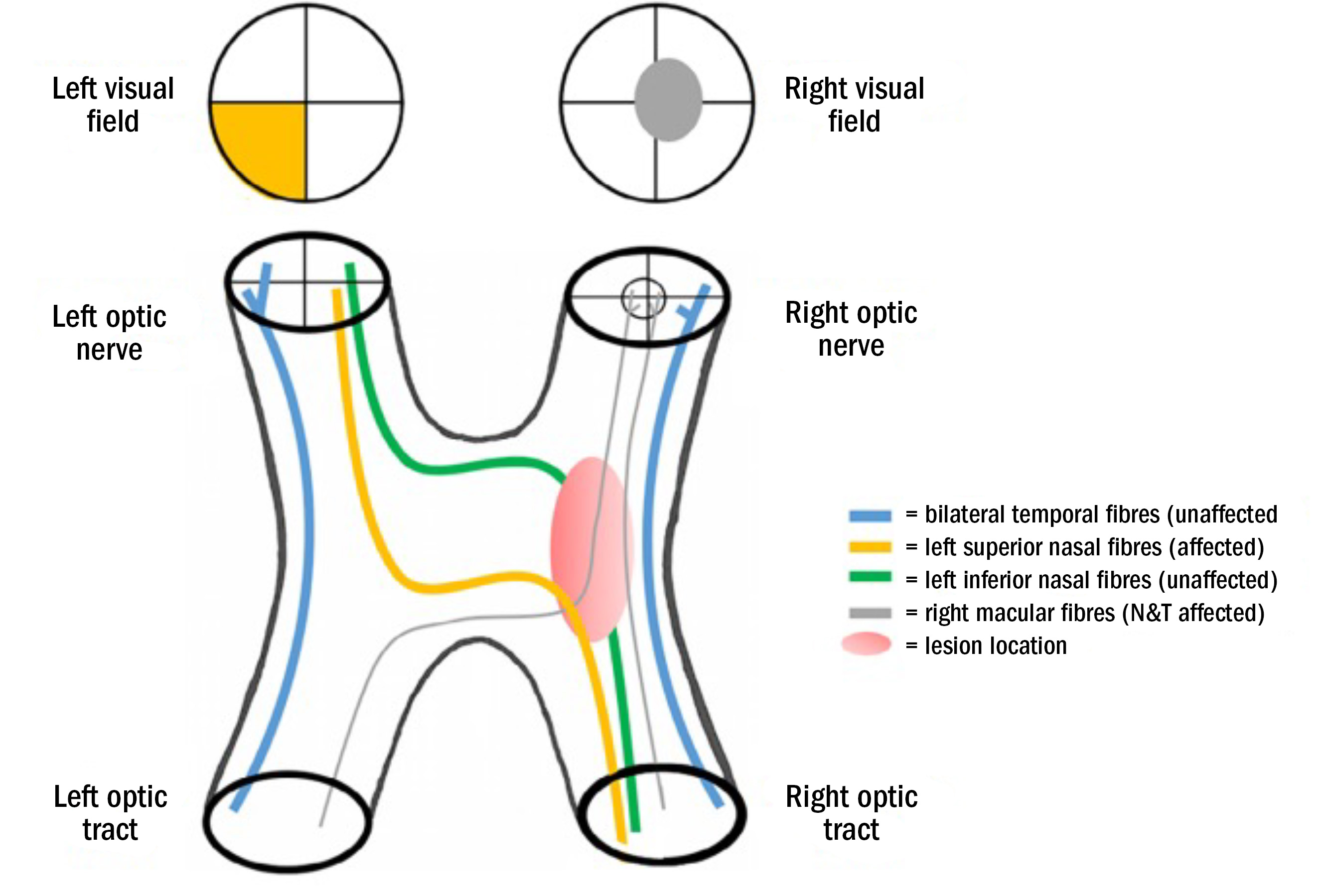

Figure 1 Example of chiasmal lesion and an atypical junctional scotoma (illustration from C Borgman6)

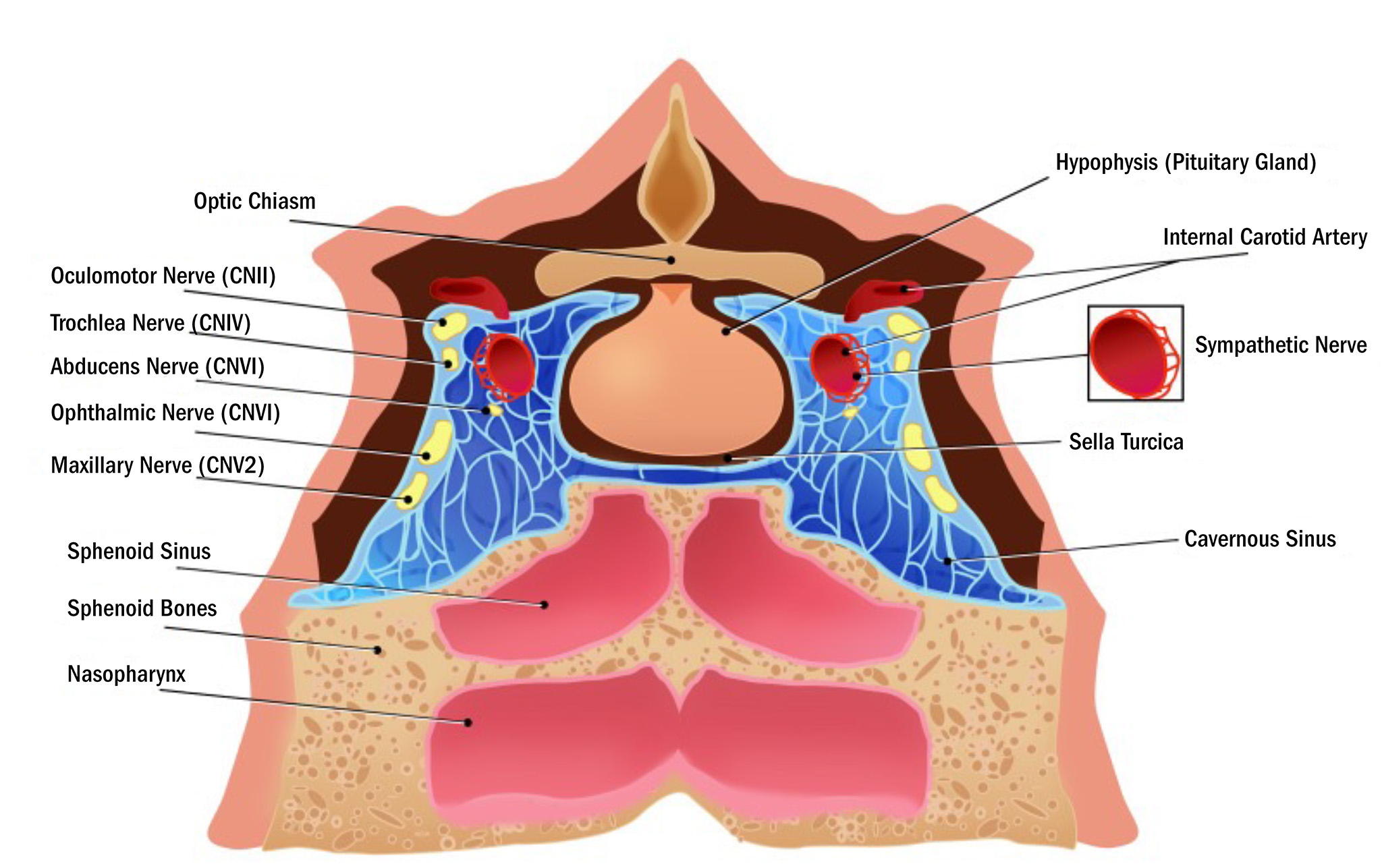

Figure 2 Transverse section of the Cavernous Sinus demonstrating the proximity and position of the pituitary gland in relation to the optic chiasm

(image by Okkes Kuybu, MD and Diana9)

He returned in mid-October, the requisite six weeks following uncomplicated bilateral cataract extractions with monofocal implants. His ophthalmologist had seen him for postoperative follow up 10 days beforehand and encouraged him to return for an up-to-date examination for new spectacles.

He was managing his distance vision well and using sunglasses but was keen to have a more precise correction for his near vision as ‘ready readers’ did not quite work for him. Having worn varifocals successfully in the past and due to his hobbies, he elected to have more varifocals dispensed into a relatively new and existing frame.

New varifocals were prescribed and the lens design was kept the same to aid adaptation.

Post operative refractive outcome: (October)

R 6/7.5 +0.25/-0.75 x 20 6/5 +2.25 Add N5

L 6/9 +0.25/ -1.00 x 15 6/5 +2.25 Add N5

Suprathreshold central fields were full. (Henson 7000)

This patient went on holiday to Australia for a month while his spectacles were being made. He continued using plano sunglasses and ready readers to ‘get by’ until the new spectacles were collected. On his return, just before Christmas, the updated varifocal correction was fitted and supplied and all seemed well.

Nothing could have surprised the dispensing team more than when the patient returned 10 days later.

It was early January, the gentleman claimed that he ‘could not read’ in his new spectacles. This issue had not been noted while on holiday using the ready readers or on collection of the new prescription. He felt that the fault lay firmly in the fitting of the varifocal. He was particularly annoyed because there had been a lot of singing over the festive period in the choir and he was struggling.

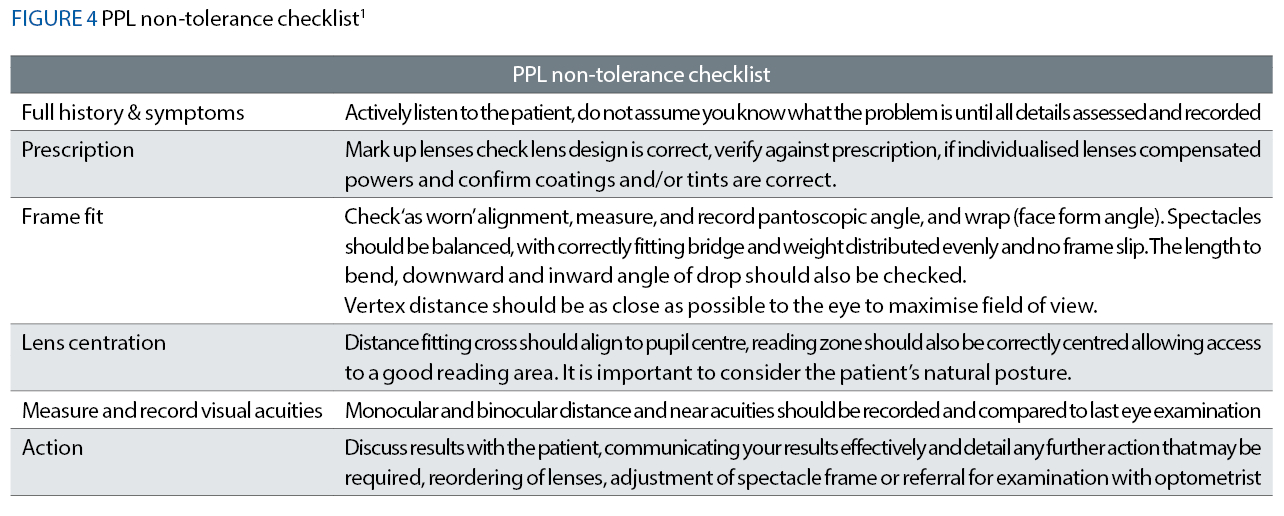

The usual suspects for varifocal non-tolerance3 were checked; vertical and horizontal centration, fit and pantoscopic tilt of the frame; lenses were checked for manufacturing defects, prescription errors, etc, but all was found to be as it should be. Before discussing alternative solutions or re-refraction, the dispensing optician took some crucial action and decided to listen to the patient read out loud, both monocularly and binocularly.

She was very surprised that indeed the patient could not read. He was very hesitant, lost his place in the reading text and the rate of reading was slower than expected. At this point, the patient was able to tell the dispensing optician that some of the N5 typeface letters in words actually appeared to be missing – he had not really noticed this at home.

Despite the sight test only having been completed two months previously, the patient was wisely rebooked for an urgent recheck. Happily, this could be done on the same day.

Re-examination results confirmed 6/6 acuities R and L in an unchanged spectacle Rx and monocular near acuities of N5 R and L with no oculomotor imbalance. However, the patient was not able to read easily or accurately when scanning to the right. The patient reported no sign of visual disturbance, headache, illness, change of health or medication.

Clearly something was wrong. Fundus examination was completely normal and there were no signs of early capsular opacification.

Full threshold central visual fields were performed (Sita Fast 24-2) and confirmed a bitemporal incongruous quadrantanopia affecting a small portion of the temporal macula hemi-field in the right eye and supero-temporal quadrant in the left field. The patient was referred urgently for a neuro-ophthalmological opinion. Local waiting times for urgent neurology appointments were six weeks.

Ophthalmology sent the patient for an urgent MRI scan, which confirmed an atypical pituitary tumour that was winding around the right optic nerve. The patient was referred for urgent trans-sphenoidal investigation and resection of the tumour.

After several months of follow up, the patient returned at the request of the neurologist for repeat field monitoring and his reading vision was back to normal in the varifocals we had initially supplied.

The pituitary tumour had been a particularly aggressive and fast-growing lesion, which impacted especially on the right optic nerve where the topology of the macula fibres affected the lateral edge of the optic nerve. In the two weeks between diagnosis and surgery, the patient had almost developed complete superior right quadrantanopia’s and reported that on waking from the general anaesthetic he was aware of almost immediate visual improvement.

A year later, the patient remained tumour-free and had managed to avoid radiotherapy. The visual field was completely restored, most likely due to the precision of the surgery and the timeliness of the intervention. With chiasmal and optic nerve lesions, typically less than 20%5 recover their visual field, resorting to visual rehabilitation techniques to enable them to read.

Discussion

At the time of referral, due to the unusual presentation of the field loss, it was difficult to ascertain what type of lesion may have been causing this field loss and so suddenly. Pituitary tumours are much less common and are often very slow to grow.

The pituitary gland, typically the size of a pea and nestled in the sella turcica is very close to the optic chiasm (see figure 2). Typically, pituitary lesions from a gradually enlarging pituitary gland produce inferior chiasmal compression as the pituitary is constrained by the sella turcica and is forced upwards. Usually benign, there are many types of pituitary growth, many affecting growth, hormone balance, fertility, etc.

In a recent US study of 400,000 cases of primary central nervous system tumours, pituitary tumours are the ‘second most frequently reported histology (16.8%), following meningioma (37.6%) and followed by glioblastoma (14.6%)’. Typical field loss begins as a superior bitemporal quadrantanopia progression to bitemporal hemianopia as the lesion increases in size.

Differential diagnoses of incongruous loss such as this are nearly always chiasmal or pre-chiasmal. Craniopharyngiomas arise from close to the pituitary gland but do not involve the glandular tissue. These benign, slow growing tumours, often present with headache, are seen in either teens/young adults or older aged adults, with an 83% five-year survival rate.8

It is important to suspect pathology in more senior patients presenting with spectacle non-tolerance, especially those which affect reading speed. The more acute forms of ocular comorbidities could be macula lesions, vascular events or optic neuropathy.

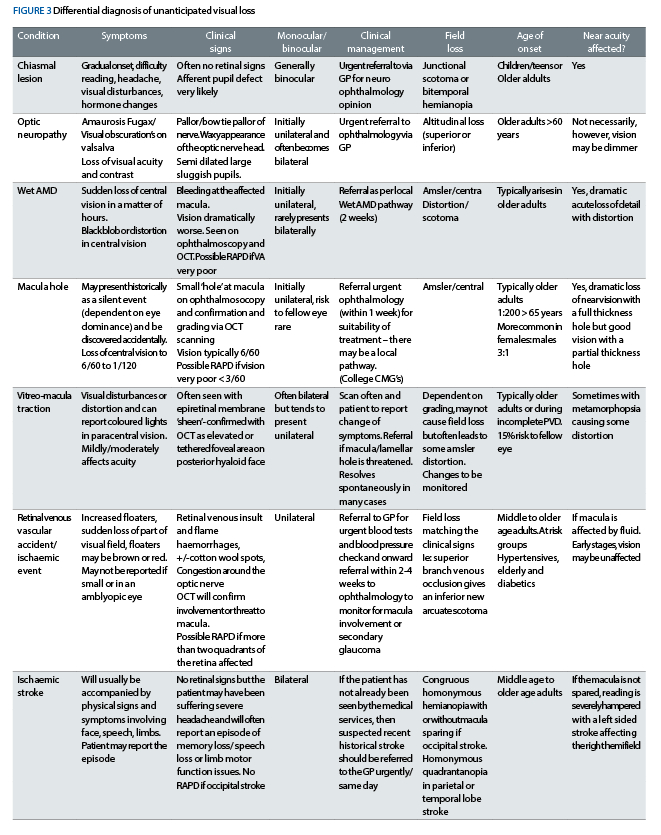

Most of these would present with other symptoms as well as generalised ‘difficulty in reading’ as summarised in figure 3 and careful questioning will guide you as to the most appropriate course of action. A quick check of the refraction in a retest may not be sufficient to rule out other more serious factors.

Figure 3 is not an exhaustive list but some of the most useful to consider when presented with a non-tolerance that does not appear to be typical. Most of these will present with acute symptoms and may not have been present during the recent sight test.

Thanks to the diligent attention of the dispensing optician who handled the initial complaint, this patient’s eye health was re-investigated in an appropriate timescale, without delay and the sight loss was restored. It would have been too easy not to have listened to the rate of reading, sending the patient away and encourage them to persevere with their varifocals.

It is important to keep in mind that pathology can arise unexpectedly several weeks following a sight test, especially where there has been a surgical intervention in the recent past and also to bear in mind that if a simple refractive error is causing issues, the issue may not lie in the spectacles but in a novo clinical concern requiring intervention urgently.

- Sarah Arnold works in an independent practice in Hampshire and is involved in the sight loss sector.

Bibliography and further reading of interest

1. Black and Black; Fundamentals of ophthalmic dispensing part 26: Presbyopia 4 – Presbyopia problem solving. Optician Online

2. Farrell – Dispensing Causes of Non-Tolerance; Optician Magazine May 2005

3. Bist J, Kaphle D, Marasini S, Kandel H. Spectacle non-tolerance in clinical practice - a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2021 May

4. Freeman C & Evans BJW. Investigation of the causes of non-tolerance to optometric prescriptions for spectacles. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt,2010; 30: 1–11.

5. Monserrate AE, De Jesus O. Homonymous Superior Quadrantanopia. [Updated 2023 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558982/

6. Christopher Borgman; Atypical junctional scotoma secondary to optic chiasm atrophy: a case report Clin Exp Optom 2019; 102: 627–630 DOI:10.1111/cxo.12903

7. Robert Y. Shih, Jason W. Schroeder, Kelly K. Koeller Primary Tumors of the Pituitary Gland: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. Published online Oct 1 2021

8. Ortiz Torres M, Shafiq I, Mesfin FB. Craniopharyngioma. [Updated 2023 Apr 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459371/

9. Kuybu O, Dossani RH. Cavernous Sinus Syndromes. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532976/

10. Clinical Management Guidelines – College of Optometrists.