The current reality

The point at which the vast majority of patients with dry eye type symptoms present could be the exam room, however in the author’s opinion it is more likely in a routine general eye exam patients will not make reporting ocular surface symptoms a priority, instead they are often mentioned during dispensing, spectacle adjustments, pre-screening or at the reception desk.

The author has found that for many patients dry eye drops are being self-selected online, in the supermarket, or from a pharmacy shelf. Patients discuss trying a bewildering number of dry eye drops as well as feeling overwhelmed by the vast choice of available products that, in fact, do not appear to help very much. As is often the case the patient attends the practice without bringing their current eye drops with the expectation the optician will instantly know the product from descriptions of ‘the bottle has a blue/white/green/red cap’ or ‘it is the one you spray’ (figure 1.)

Figure 1: The unknown eye drop

More than occasionally, patients say: ‘The optician who tested my eyes two years ago gave me a bottle at the end of the appointment they found in a draw, and that seemed to help, but it ran out so I’ve been suffering ever since.’ Check the clinical notes from that visit to see if in fact drops were prescribed and details of the product supplied, but do not be too surprised if there is no reference of this in the patient record. Maintaining clear contemporaneous records is essential as this enables all practitioners that follow to understand exactly what has been discussed, advised and prescribed and is also a requirement of the General Optical Council (GOC) Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians.1

Signs and Symptoms

Typical symptoms of the umbrella term dry eye disease (DED) are dryness (although this is often not readily recognised by the patient), excessive tearing (epiphora) more so in cold and/or windy conditions, variable vision improved with blinking, discomfort on opening and closing eyelids, irritation, even occasional sharp stabbing pain, lids feel reluctant to open on waking and perhaps pain when they do, stinging, burning, ‘tired eyes’ or foreign body sensation.2

Table 1: Dry eye disease signs and symptoms

These common symptoms are generally exacerbated in warm, dry atmospheres, particularly if doing attentive tasks; computer use, using a digital screen (mobile phone, etc), driving, hot/cold air streams or even reading. These symptoms are not just minor irritations, they significantly impact patients’ daily activities, workplace productivity and quality of life.3 A quality of life measure reported that 25% of patients with DED felt unhappy or depressed, 34% felt frustrated with daily activities and 11% needed to decrease work time.3,4

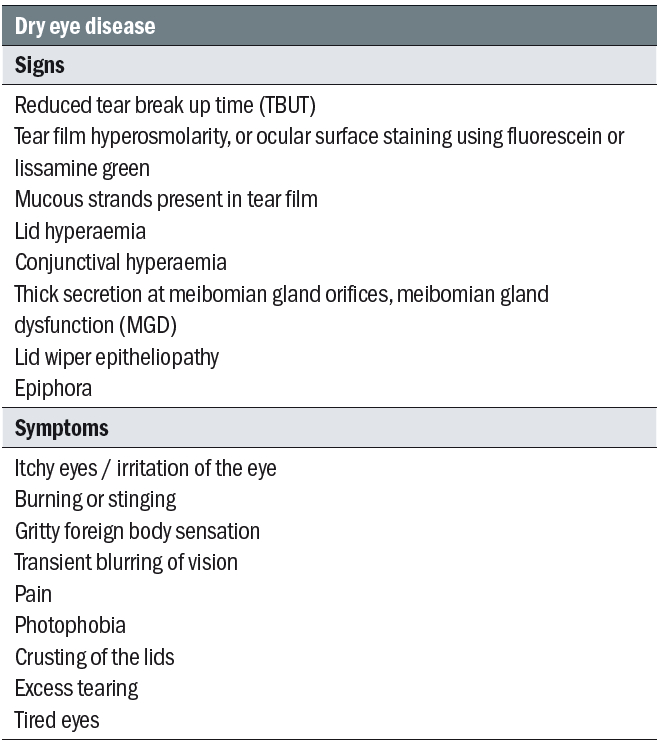

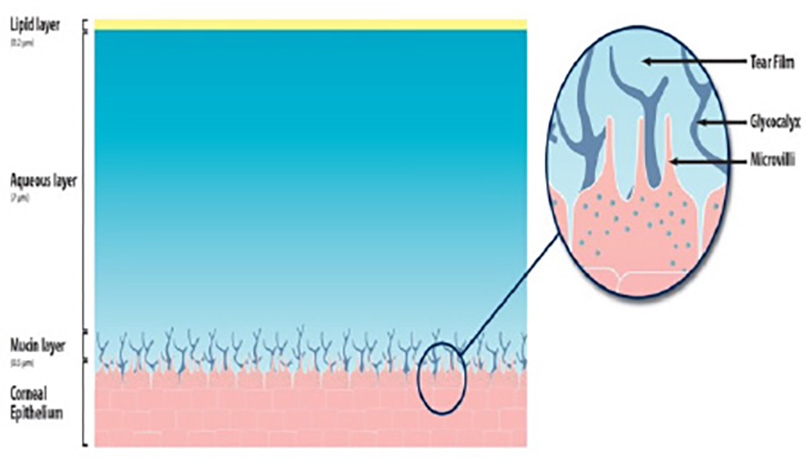

A reduction in the quality of vision in DED is not at all unusual or surprising, normally after blinking a smooth and stable tear film is formed, this then gradually thins until it breaks up, it will tend to do this more centrally, closer to the visual axis, than at the cornea’s periphery, just where critical vision is required, it is then compromised.5 Typically, dry spots begin to form in a normal tear film at 10-12 seconds post-blink, creating optical aberrations on the surface epithelium6 (figure 2). In the exam room, or during pre-exam tests outside the exam room, for a patient with DED it is only logical to assume these tear film dry spots, perhaps occurring at a frequency of single figure seconds will adversely affect the quality of images or the accuracy of readings.

Figure 2: Tear break up illustrated using sodium Fluorescein. Image: Eyerounds.org

Quality of life measures report DED adversely affected driving at night for 32% of sufferers, with 25% feeling reading or computer use was affected.4 Topical instillation of dry eye drops has been shown to increase tear break-up time by 60%.5 Correspondingly, in the author’s experience most patients with DED report subjective improvement in vision with dry eye drops, but not necessarily for a significant period. However, it has been more difficult to find evidence that a particular formulation is superior when it comes to screen use for instance. Two head-to-head randomised controlled trials compared topical lubricant eye drops for treating ‘digital eye strain’ found differences unlikely to be clinically meaningful.6,7

The negative impact, and often-overlooked aspect, of vision quality and stability in DED, relative to physical symptoms is important, The eye is a complex optical system with the tear film air interface being the first and major contributing refractive surface through which light travels to reach the retina. Evaporation of the tear film between each blink can cause transient aberrations and reduced optical quality of the image.8 In a study comparing 50 normal eyes and 50 eyes with DED, patients with dry eye and unstable tear film were found to have a significantly worse quality of vision and optical scatter. They were also noted to have fluctuation of vision between blinks.9

A good tear film reduces the scattering of light and helps in partially correcting optical aberrations occurring due to irregularities on the ocular surface. A patient with unmanaged DED is simply not going to see the world, perceive your practice, the outcome of the onerous ‘which is better, 1 or 2?’ tests (for many DED patients their judgment will be variable and contradictory), or your dispensing skills, as well as we would like. The author recalls a conversation while working in the USA with an anterior segment surgeon. ‘I could be the best Lasik or cataract surgeon in the USA, but my patients won’t appreciate that if they have a garbage tear film!’ The same could be said of the great work we do in practice.

Prevalence

Estimating the prevalence of DED is difficult as there are still definitions that are varied, however, if we take a definition of DED as frequency of symptoms, having at least one of several symptoms of dry eye often or all the time, such as foreign body sensation, dryness, irritation, itching or burning, then two separate studies in the United Kingdom and Korea, using this form of definition identified a similar prevalence of symptomatic DED of around 20%.10,11

In 2017, a two-year project looking into all aspects of DED reported, consisting of 12 subcommittees made up of 150 experts from 23 countries reported, referred to as the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Dry Eye Workshop II or TFOS DEWS II.12 It is a weighty report in terms of quantity and quality of information and its impact. Its well-known final definition of DED is worth stating:2

‘Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterised by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory

abnormalities play etiological roles.’

With a well-timed appearance, in the journal Contact Lens and Anterior Eye in June of this year appeared ‘The epidemiology of dry eye disease in the UK: The Aston dry eye study’,13 using a TFOS DEWS II dry eye definition criteria the study reported a prevalence of 32.1%. This unique insight into DED in the UK took the opportunity to additionally and separately use the Women’s Health Study (WHS)14 criteria, which is based on symptoms or a prior dry eye diagnosis, for prevalence analysis, this revealed a figure of 29.5%.

It is difficult to measure, but the consensus is that the prevalence of DED may be increasing,15 with perhaps an ageing population, increased use of medication with DED side effects, increased screen time, more people living with systemic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes, living our lives in warm, dry environments, etc. Therefore, like myopia progression, it a is a modern, significant, growing eye disease that will have a large impact on the lives of our patients.

Sounds like dry eye, but is it?

Before discussing specific physiologic causes of what seems like an epidemic of dry eye symptoms, exacerbated by the factors mentioned in the previous paragraph, eye care professionals (ECPs) need to be aware that dry eye symptoms can overlap with other forms of ocular surface disease, meaning less common conditions can be misdiagnosed as dry eye. In the author’s opinion, not every patient with ocular surface symptoms has, or indeed possibly could have, dry eye. Many times, through patient self-diagnosis, inappropriate treatments are used, sometimes for years meaning a delayed accurate diagnosis, potentially exacerbating the underlying condition.

For instance, corneal dystrophies (epithelial, subepithelial, stromal and endothelial) often get worse over time,16 as does dry eye. Symptoms include glare, pain or discomfort, light sensitivity, dry eye and in some cases a reduced level of vision, occasionally they progress to recurrent corneal erosions (RCE).17

RCE can also be caused by ocular trauma, corneal abrasions are the most common cause of eye injury in children.18 Corneal dystrophies and RCE may benefit from some forms of dry eye treatments to prophylactically prevent the worst of the condition manifesting, keeping the ocular surface moist is almost always helpful.17 The underlying cause should not be overlooked as this may mean opportunities to refer for ophthalmology treatment are missed.

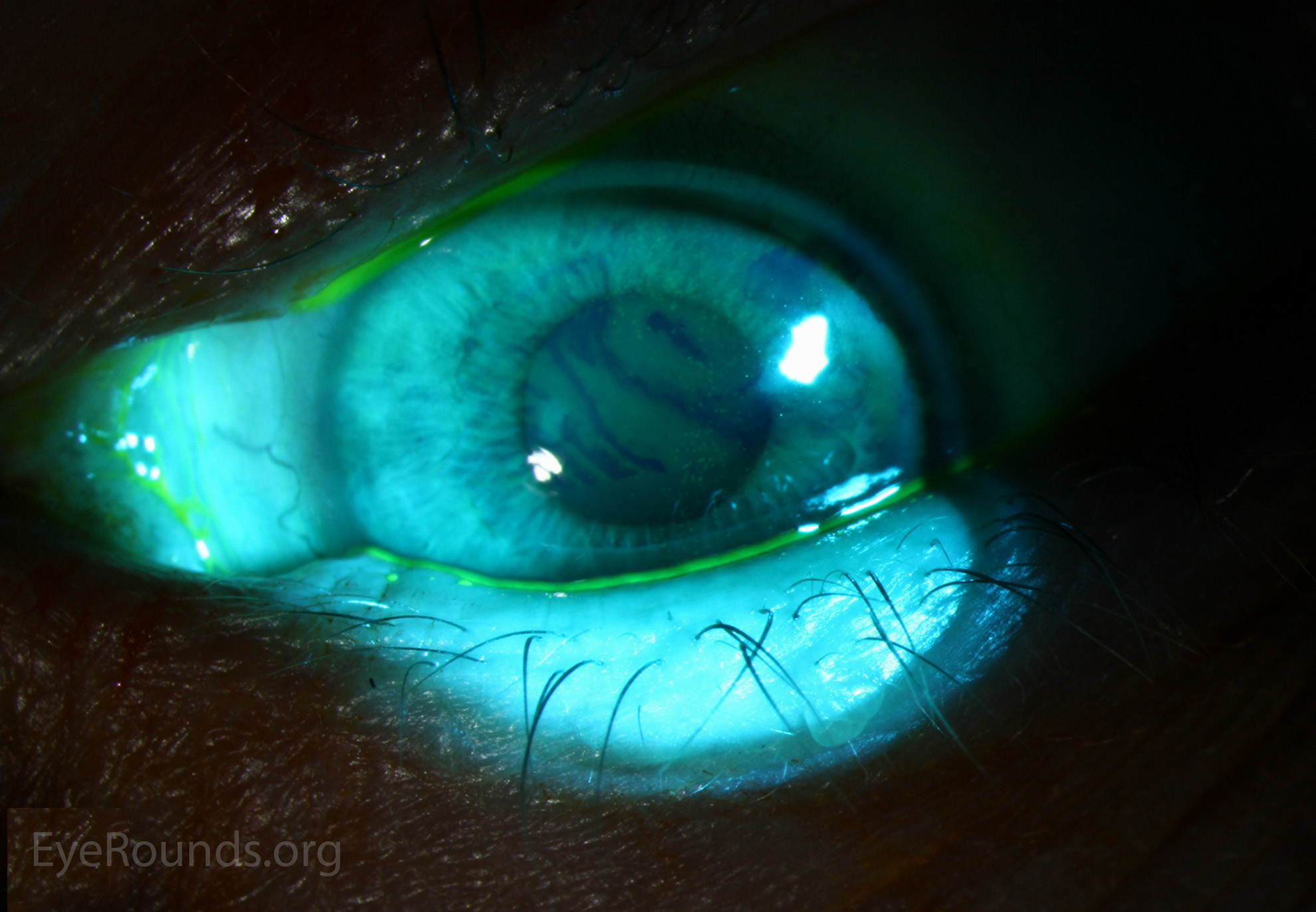

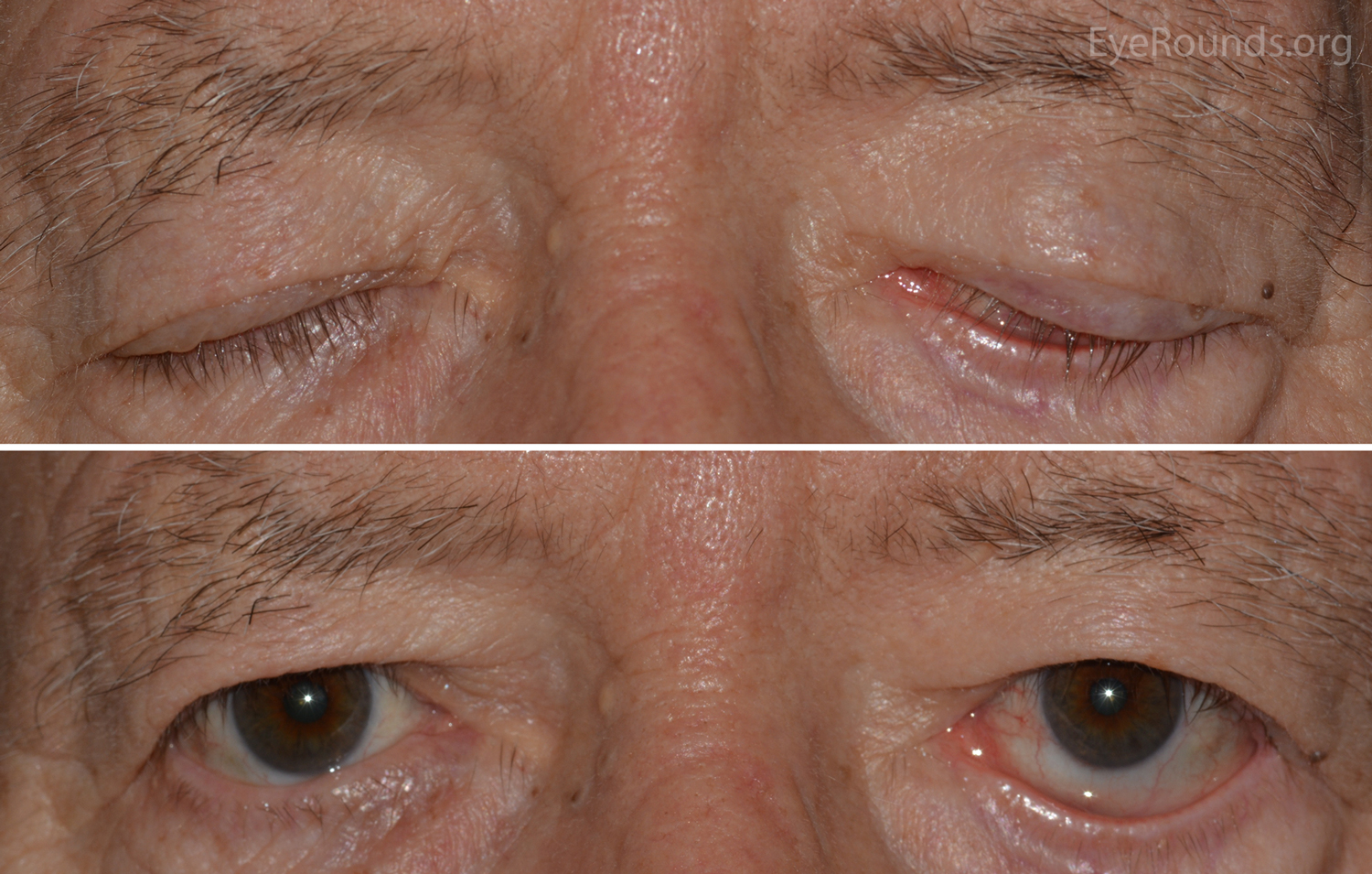

Lid ectropion, entropion and trichiasis (figure 3) are more disorders, more prevalent with increasing age19 that can mimic dry eye symptoms and when misdiagnosed can result in missed opportunities to relieve symptoms and avoid corneal trauma, perhaps even corneal ulceration. For instance, in entropion, referral for lid surgery and even a bandage contact lens while waiting will help, trichiasis can be instantly solved by the removal of offending lash or lashes at the practice slit-lamp.20

Figure 3: Entropion with trichiasis. Image: Eyerounds.org

Conjunctivochalasis (CCH) is another common ageing condition that can lead to instability and even disruption of the tear film with symptoms also resembling DED. It occurs when the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva fill up the lower fornix and obliterate the lower reservoir that is essential to refresh the tear film with every blink.21 The normally strong, fibrous tissue becomes a fibro-vascular gel that loses the ability to hold the conjunctiva in place. The conjunctiva then fills the reservoir with tissue, leaving no room for the tear film reservoir causing the tears to overflow the lid margin and/or are unable to drain through a now obstructed puncta.

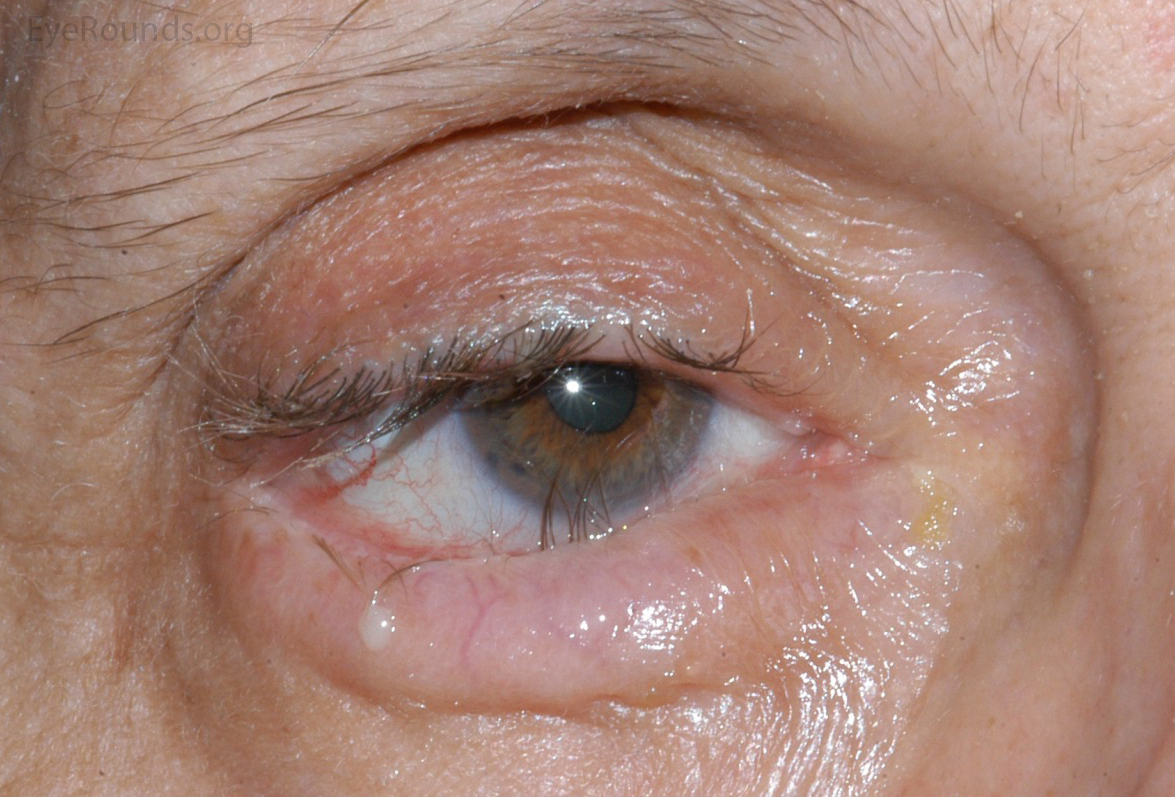

Occasionally a patient will exhibit incomplete lid closure, lagophthalmos22,23 (figure 4), perhaps as a result of Bell’s palsy, entropion or ectropion, which can result in a more severe dry eye condition where the more conventional dry eye treatment approaches do not address the true underlying lid anomaly, again through exposure keratopathy the risk of corneal ulceration is increased.

Figure 4: Left Lagophthalmos during eyelid closure. Image: Eyerounds.org

The richly innervated corneal tissue is one of the most powerful pain generators in the body.24 Corneal neuropathic pain results from dysfunctional nerves causing perceptions such as burning, stinging, eye-ache and pain, very similar symptoms to dry eye, but here the abnormal condition lies with the corneal nerves themselves. Original causes can include refractive surgery, dry eye disease, Sjögren’s Syndrome, neuralgia associated with herpes virus, benzalkonium chloride (BAK) preserved eye drops, Accutane, chemotherapy and radiotherapy to mention a few.25 A more detailed discourse on this fascinating aspect of ocular surface disease is beyond the scope of this article.

Understanding these possible alternative reasons for symptoms that mimic dry eye disease emphasises the importance of a discussion with a registered ECP rather than self-diagnosis as the patient can then be directed to appropriate further investigation where necessary.

Classification of dry eye

Just as the generic term ocular surface disease covers a multitude of conditions, even when a singular diagnosis of ‘dry eye’ is made, to the exclusion of other conditions, this is still an ‘umbrella term’, it is still not specific enough. To better understand the nature of a patient’s dry eye and be in a position to offer the most appropriate management or treatment a deeper understanding of the different sub-types of dry eye is required. Going back 16 years, which in turn updated a 1995 consensus, The Report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Work Shop (2007 )26 proposed two major classifications of DED; evaporative dry eye (EDE) and aqueous deficient dry eye (ADDE) (figure 5).

Figure 5 Tear film

Evaporative dry eye

Increased evaporation from the tear film, adversely affected by changes to meibum production (quantity and/or quality) as a result of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD).27 The EDE form can be sub-divided; it may be intrinsic, where the regulation of evaporative loss from the tear film is directly affected, eg by MGD with a low quantity/quality of vital evaporative retarding lipid delivery, low blink rate, and the effects of drug action etc or extrinsic, for instance vitamin A deficiency, preservative toxicity, cosmetics, contact lens wear etc.

Aqueous Deficient Dry Eye (ADDE)

This is caused by reduced lacrimal secretion and can be subdivided; Sjögren syndrome dry eye directly linked to the systemic disease itself and non-Sjögren syndrome dry eye as a result of, for instance, lacrimal gland duct obstruction or systemic drugs etc.27

In 2017, the TFOS DEWS II Tear Film Report defined clinical DED, characterised by loss of tear volume, more rapid breakup of the tear film and increased evaporation of tears from the ocular surface.27

The most appropriate treatment or management approach would be best focused on which of the two forms is primarily causing a problem, so for instance MGD would benefit from improving the meibomian gland function, while an ADDE would possibly primarily benefit from punctal occlusion to retain more tear volume on the ocular surface. Even in the sub-divisions of the two main categories a targeted approach can pay dividends, so helping the blink function or avoiding toxicity reactions (eye drops, cosmetics, etc).

Lemp at al29 identified the relative prevalence of the two major classifications of dry eye; EDE and ADDE, in a study involving in total 299 normal subjects and DED patients (218 women and 81 men) across 10 sites in the EU and the USA. The results revealed of the 224 subjects classified with DED, 79 were classified with only MGD, whereas only 23 were classified as purely aqueous deficient, and 57 showed evidence of both MGD and aqueous deficiency. Sixty-five subjects could not be definitely classified. Overall, 86% of these qualified DED patients demonstrated signs of MGD. The proportion of subjects exhibiting signs of evaporative dry eye resulting from MGD far outweighed that of subjects with pure ADDE in a general clinic-based patient cohort.29

It can be seen that patients can experience both subtypes of DED, or a mixed dry eye additionally, irrespective of the underlying cause a vicious cycle can occur. Evaporation, whether due to lack of tear volume or deficiency in the lipid layer, followed by a cascade of inflammatory events lead to increased evaporation and so on, perpetuating the cycle.30 Breaking this cycle with a targeted treatment regime is essential but when managing, treating, and advising patients with DED it is important that dispensing opticians, contact lens opticians and optometrists recognise the limits of their individual scope of practice and when necessary refer appropriately.

Summary

In order to treat or manage an ocular surface disease, it is vital a correct diagnosis is made, ECPs have to be aware that dry eye and other forms of ocular surface disease can have very similar symptoms, and that it is all too easy for patients, other health care practitioners and non-ECPs to incorrectly diagnose a condition and incorrectly treat it. Equally, by understanding the forms of DED provides an opportunity to provide a more appropriate management or treatment option that will benefit our patients.

- Andrew D Price FBDO(Hons)CL MBCLA, CEO of ADP Consultancy and ADP-EyeCare originally set-up in 1994, is a clinician running contact lens and dry eye clinics, a principal investigator in clinical trials, an industry/professional services consultant, educator, lecturer and author. Holding Honours Fellowship of the Association of British Dispensing Opticians (ABDO) in contact lens practice. He received certification in ophthalmic assisting during work in ophthalmology practice in the USA. His experience encompasses managing/owning his own contact lens practice, working in laser vision and ophthalmology clinics in the UK and USA. Price has had many articles published and presented over 300 lectures and workshops, in the UK and abroad on contact lenses and dry eye disease. He was involved, with others, in developing Eye Drops Database, a website devoted to the ocular surface with separate professional and patient sections. He is a past ABDO National Clinical Committee and Optometry Wales Board member. Guest lectured for the ABDO and Anglia Ruskin University.

References

- General Optical Council. 8.1 Maintain adequate patient records. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. London: General Optical Council. 2016. p13.

- Craig P, Nichols KK, Akpek E, Caffery B, et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and classification Report. The Ocular Surface. 2017;15(3): 276-283. Available From: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1542012417301192

- Asbell PA. Increasing importance of dry eye syndrome and the ideal artificial tear: consensus views from a roundtable discussion. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2006; 22:2149-2157 https://doi.org/10.1185/030079906x132640

- Nelson JD, Helms H, Fiscella R, et al. The relative burden of dry eye in patients’ lives: comparison to a US normative sample. Invest Ophthalmology Vis Sci 2005; 46:46-50. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.03-0915

- Montes-Mico R, Cervino A, Ferrer-Blasco T, Garcia-Lazaro S, Madrid-Costa D. The tear film and the optical quality of the eye. The Ocular Surface. 2010; 8(4):185-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70233-1

- Rajendraprasad R, Kwatra G, Batra N. Carboxymethyl cellulose versus hydroxypropyl methylcellulose tear substitutes for dry eye due to computer vision syndrome: comparison of efficacy and safety. Int J Appl Basic Med Res 2021;11(1): 4–8. https://doi.org/10.4103%2Fijabmr.IJABMR_399_20

- Skilling FC, Weaver TA, Kato KP, Ford JG, Dussia EM. Effects of two eye drop products on computer users with subjective ocular discomfort. Optometry. 2005; 76(1): 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1529-1839(05)70254-2

- Montés-Micó R, Alió JL, Muñoz G, Pérez-Santonja JJ, Charman WN. Postblink changes in total and corneal ocular aberrations. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(4):758–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.06.027

- D’Souza S, Annavajjhala S, Thakur P, Mullick R, Tejal SJ, Shetty N. Study of tear film optics and its impact on quality of vision. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020 Dec;68(12):2899-2902. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.ijo_2629_20

- Vehof J, Kozareva D, Hysi PG, Hammond CJ. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye disease in a British female cohort. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98(12):1712-7. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305201.

- Na KS, Han K, Park YG, Na C, Joo CK. Depression, stress, quality of life, and dry eye disease in Korean women: a population-based study. Cornea 2015;34(7):733e8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ico.0000000000000464

- Tear Film & Ocular Society. TFOS DEWS II Reports. Available from: http://www.tfosdewsreport.org/report-tfos_dews_ii_report/36_36/en/

- M Vidal-Rohr, JP Craig, LN Davies, JS Wolffsohn. The epidemiology of dry eye disease in the UK: The Aston dry eye study. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye. 2023; 46(3): 101837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2023.101837

- Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, Jalbert I, Lekhanont K, Malet F, et al. TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report. The Ocular Surface. 2017;15(3):334–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003

- Boboridis KG, Messmer EM, Benitez-del-Castello J, Meunier J, et al. Patient-reported burden and overall impact of dry eye disease across eight European countries: a cross sectional web-based survey. British Medical Journal Open. 2023; 13: e067007. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067007

- Bourges JL. Corneal dystrophies. Journal Français d’Ophthalmologie. 2017 ; 40(6) : e177-e192. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfo.2107.05.003

- Millar DD, Hasan SA, Simmons NL, Stewart MW. Recurrent corneal erosion: a comprehensive review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13: 325-335. https://doi.org/10.2147%2FOPTH.S157430

- Jolly R, Arjunan M, Dahlmann-Noor A. Eye Injuries in children – incidence and outcomes: an observational study at a dedicated children’s casualty. European Journal of Ophthalmology. 2018;29(5). https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672118803512.

- Hakim F, Phelps P. Entropion and ectropion. Disease-a-month. 2020; 66(10): https://dio.org/10.1016/j.disamonth.2020.101039

- College of Optometrists. Clinical guidelines Trichiasis. Available from: https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/trichiasis#:~:text=The%20optometrist%20may%20decide%20to,to%20relieve%20the%20patient’s%20symptoms

- Maramlidou A, Palioura S, Dana R, Kheirkhah. Medical and surgical management of conjunctivochalasis. The Ocular Surface. 2019;17(3): 393-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tos.2019.04.008

- MacIntosh P, Fay A. Update on ophthalmic management of facial paralysis. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2019;64(1): 79-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.06.001

- Rani MR, Deepa M, Gitanjali VC, Tinu SR, et al. Lagophthalmos: An etiological lookout to frame the decision for management. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022; 70(8): 3077-3082. https://doi.org/10.4103%2Fijo.IJO_3017_21

- Downie LE, Bandlitz S, Bergmanson JP, Craig JP, BCLA CLEAR – Anatomy and physiology of the anterior eye. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye. 2021; 44(2): 132-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2021.02.009

- Goyal S, Hamrah P. Understanding Neuropathic Corneal Pain--Gaps and Current Therapeutic Approaches. Semin Ophthalmol. 2016;31(1-2):59-70. https://doi.org/10.3109%2F08820538.2015.1114853 PMID: 26959131; PMCID: PMC5607443.

- The Ocular Surface ISSN: 1542-0124. (No authors listed ). The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). 2007;5(2):75-92.

- Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. The Ocular Surface. 2017;15(3): 276-283

- Craig JP, Nichols KK., AkpeK EK, Caffery B, et al. TFOS DEWS Definition and Classification Report. The Ocular Surface. 2017; 15(3): 276-283https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008

- Lemp, MA, Crews, LA, Bron, AJ, Foulks, GN, & Sullivan, BD. (2012). Distribution of aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry eye in a clinic-based patient cohort: a retrospective study. Cornea, 31(5), 472-478.

- Bron AJ, De Paiva CS, Chauhan SK, Bonini S. et al. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. The Ocular Surface. 2017; 15: 438-510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.011