Over your years of practice, there will be an inevitable accrual of contact lens horror stories. Your archives will likely include multiple cases of overnight wear in lenses intended for daily wear, the reuse of the same lenses well past their recommended expiration, and at least once in your career you will peer into the slit lamp bewildered as it dawns on you that the lenses you had originally dispensed to the patient are not the ones being worn. Welcome to the joys of contact lens aftercare.

Yet given that non-compliance among contact lens wearers is reported to range between 40-91%,2 should any of these episodes come as a surprise? The stats certainly support the need for regular contact lens reviews, but how do we ensure patients see the value in attending appointments and commit to best practice principles?

If you could rip up the rule book and start with a blank piece of paper, what would your contact lens practice approach look like? How would you maximise contact lens performance, influence behaviour, and ensure long term retention?

This article summarises the BCLA CLEAR Evidence Based Practice (EBP) report pertaining to contact lens aftercare, covering application and removal, dropouts, and long-term care. The article builds on the previous article on BCLA CLEAR Evidence based contact lens practice part 1, which covered lens fitting and selection (Optician 29/9/23).

New wearers - application/removal

For some patients the first hurdle is the most challenging. Although lens handling is considered a major contributor to contact lens dropout for new wearers, there is surprisingly little evidence supporting current lens handling and training practices. For example, the origin of requiring a patient to apply and remove a lens a minimum of three times before leaving the practice does not appear in the scientific literature.

Dropout is not the only issue associated with lens handling; there have been various incidents of prolonged ocular retention of lenses, with some reports describing retention over several decades. And while patient fingernails ought to be kept short to reduce bacterial load, the BCLA CLEAR EBP report highlights the absence of peer-review publications on nail-induced injury during lens handling.

In children and teenagers, initial lens handling may be more challenging, although this seems to subside by the six-month mark. For some patients this could necessitate a longer teach appointment (by around 15 minutes when comparing younger with older children).

A prudent approach for any neophyte would be to arrange a follow-up call during the first week to review progress and identify any further support needs. Digital remote care options offer a useful method of providing extra lens handling coaching, allowing the patient to practise in the comfort of their own home environment.

New patients are likely to benefit from more regular initial reviews than established wearers, especially within the first few months when the chance of dropping out of lens wear is higher. Making use of a range of educational resources is likely to help support with instilling best practice routines and proactively requesting patients to regularly reflect by asking themselves questions such as those outlined in figure 1.

Figure 1: BCLA educational resources available to support new wearers and questions to identify a need to seek additional contact lens care11

Adaptation

Single vision soft

Conventional practice has involved imposing lens wearing schedules on new wearers, which typically requires gradually building up lens wear times. More recently, such advice has been challenged. Studies using various lens replacement modalities and different soft lens materials have concluded that, at least for single vision soft lenses, there is no significant difference between a fast (such as immediate full-time wear) and gradual approach to adaptation.3

It may, therefore, be more practicable to discuss which approach is compatible with the patient’s lifestyle and personal preferences. With respect to toric lenses: caution is advised when prescribing unilateral (vertical) prism ballasted lenses to avoid the risk of exacerbating or inducing vertical heterophoria.

Rigid corneal lenses (RCLs)

On average RCLs require an adaption period of one to three weeks and a gradual adaptation approach ought to be considered. Symptoms of dryness and discomfort during the first 10 days may be helpful in predicting which individuals are less likely to adapt. A courtesy touch point within this period may be useful to provide appropriate advice and support.

Presbyopic solutions

Despite the potential to forego gradual adaptation periods for single vision soft lens wear, wearers of other lens designs may benefit from the slower approach. Some neophyte multifocal wearers may initially experience ghosting, blur and problems with night driving. Such issues are usually short-lived and generally subside within the first two weeks of wear.

Other presbyopic lens solutions such as monovision may present issues with binocular rivalry and image suppression. Patients may find this impacts specific occupational tasks or (intermediate) distances; run the risk of existing heterophorias decompensating; and disruptions to stereopsis may even induce changes to patient gait. Hence, eye care professionals (ECPs) have much to consider when making prescribing decisions and dispensing advice regarding adaptation.

Care systems

Deciding on a lens care system should be based on more than efficacy levels; aspects such as ease of use and comfort are also important. Globally, the majority (88%) of soft reusable contact lens wearers use multipurpose disinfecting solutions (MPDS).10 For these wearers a rub and rinse step to loosen and remove lens surface bound organisms should be advised as it can help reduce risk of a contact lens infection by approximately 3.5 times. Since the introduction of newer solution components, enhanced wetting agents and more regular replacement modern lens materials, solution-related complications such as corneal staining and discomfort are less common.

Hydrogen peroxide systems are often recommended as a troubleshooting option, and linked to benefits such as better compliance, longer comfortable wearing time (in SiHy wearers) and lower complication rates.

Adherence to correct cleaning and lens storage processes is another area where compliance is often poor. Non-compliance can lead to the build-up of biofilms in lens storage cases. Simple steps such as rubbing the case followed by rinsing, wiping with a tissue and leaving to air dry can remove nearly 90% of the bacterial load.4

Aftercare frequency

Contact lens aftercare intervals have been subject to debate, with a landmark paper recommending contact lens recall intervals relative to the risk of complications.5 In the absence of adverse findings/symptoms, recommended recalls should range from six months for overnight wear lenses, every 12 months for reusable lenses, and up to two years for soft daily disposables. Naturally, this is not without caveats, for example, some individuals are more vulnerable to frequent refractive changes and thus will need to be seen more often (every six months for progressive myopes and 12 months for advancing presbyopia).

Those new to contact lens wear are initially advised to be seen more frequently, given they are more prone to early drop out. As new research emerges it will be interesting to see how this influences future aspects such as recall frequency trends, service delivery platform choice (for example face to face vs remote) and the role artificial intelligence (AI) may play in contact lens service provisions.

The absence of symptoms does not imply an absence of complications. One study reported over 50% of asymptomatic patients to have at least one complication requiring intervention, which was only detected during a routine aftercare visit.6 Thus, the aftercare visit provides the perfect opportunity to address problems of which the patient may or may not be aware.

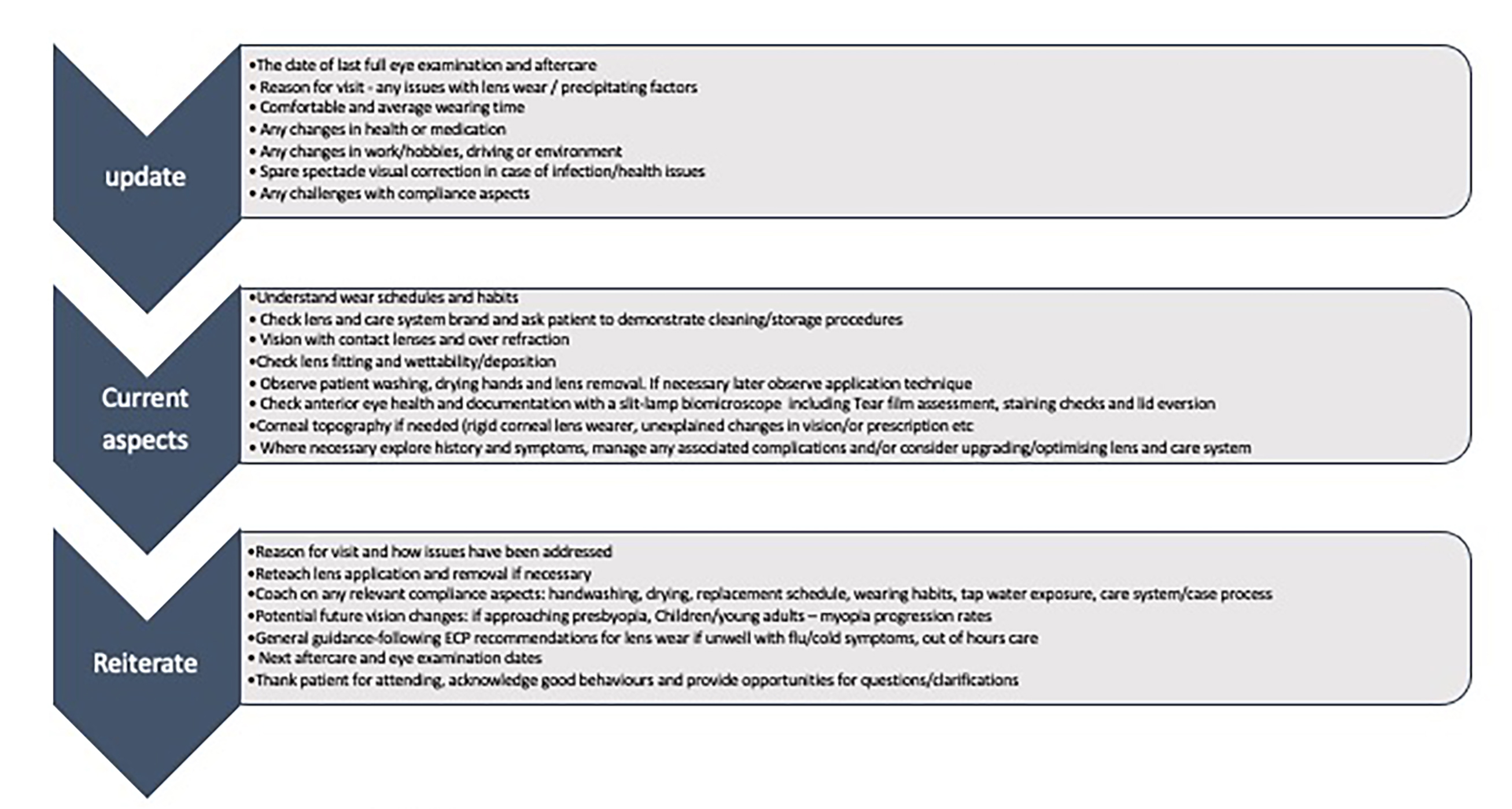

Aftercare routine

The BCLA CLEAR EBP report provides a comprehensive recommended aftercare routine, neatly divided into three areas. Firstly, gathering updates such as identifying the motivation behind the visit, understanding any changes from previous visits such as new lifestyle or health issues. Secondly, a review of current aspects to explore the lens fitting, lens performance, patient related factors, lens-eye interactions, and ocular health. And finally, the reiteration of key findings, advice and management plans that could influence future lens wear. For more detail, see figure 2.

Figure 2: Recommended aftercare routine, adapted from Wolffsohn1

Effective questioning may be complemented through the use of questionnaires, which can be helpful in gaining insights during the history taking aspect of the appointment.

Patient observation is also important in providing clues that could influence contact lens success, for example:

- Blink habits – incomplete blink can double the risk of dry eye disease.

- Non-compliant behaviours – handwashing/drying/handling/cleaning procedures.

- Patient related response to clinical examination – photophobia/discomfort/resistance.

In addition to assessing the lens fitting characteristics and visual performance, a detailed inspection of the contact lens surface can offer further information about impending issues or the source of existing problems. For example, contact lens wettability reflects how much of the lens surface is covered by the tear film and is most commonly assessed in practice by observing the non-invasive break up time on the contact lens surface.

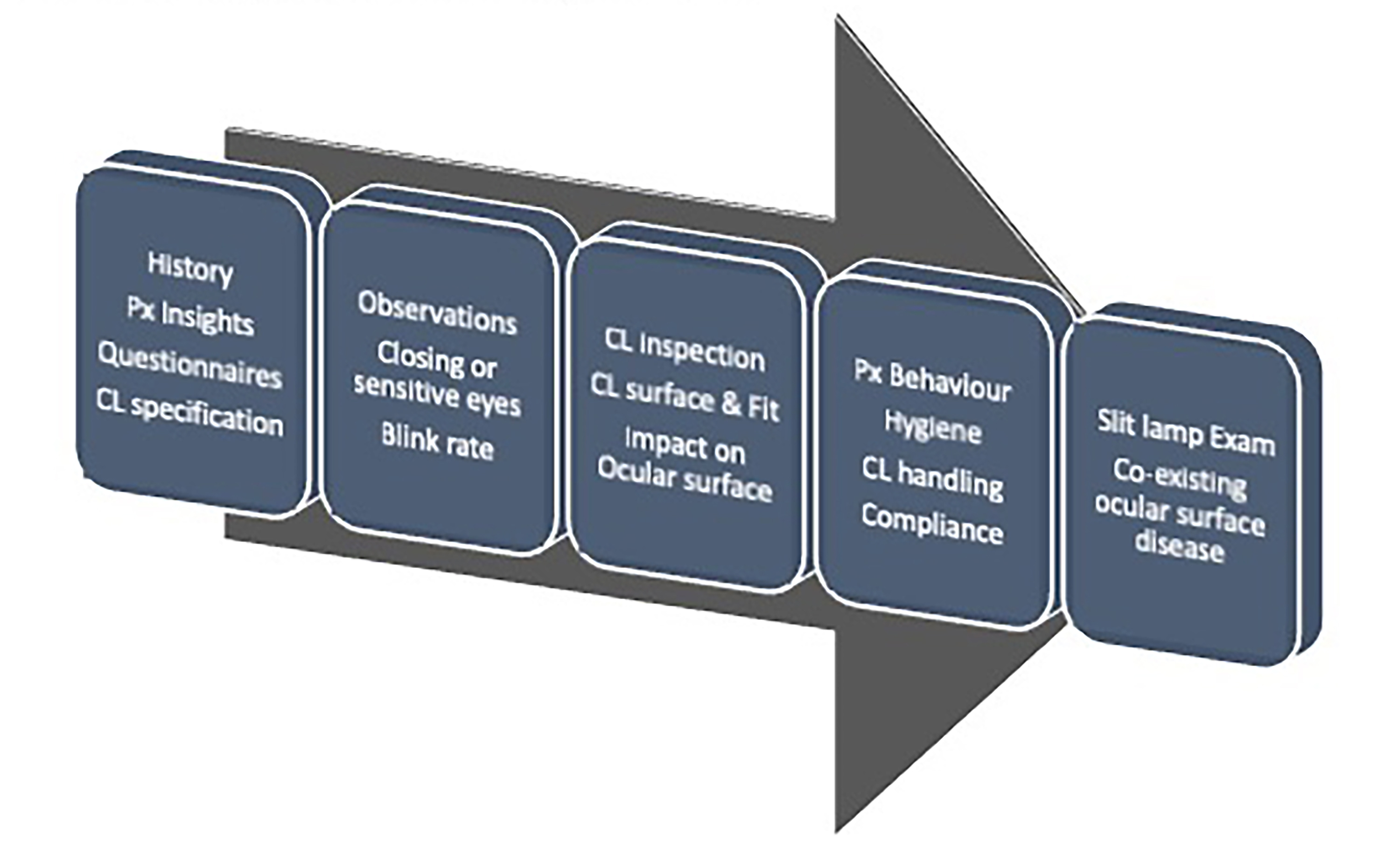

A review of best practice slit lamp routines, including ocular surface assessments was covered in the previous CLEAR article (EBP-part 1). Owing to potential disruptions to the tear film; a logical slit lamp routine usually begins with the least invasive aspects before moving onto the most invasive. The management of contact lens related complications was covered in detail in a previous article, but the presence of adverse clinical signs is not always attributable to contact lens wear, for example low levels of corneal staining can also present in non-wearers. Figure 3 highlights a logical overall approach.

Figure 3: Suggested patient assessment routine

Contact lens retention

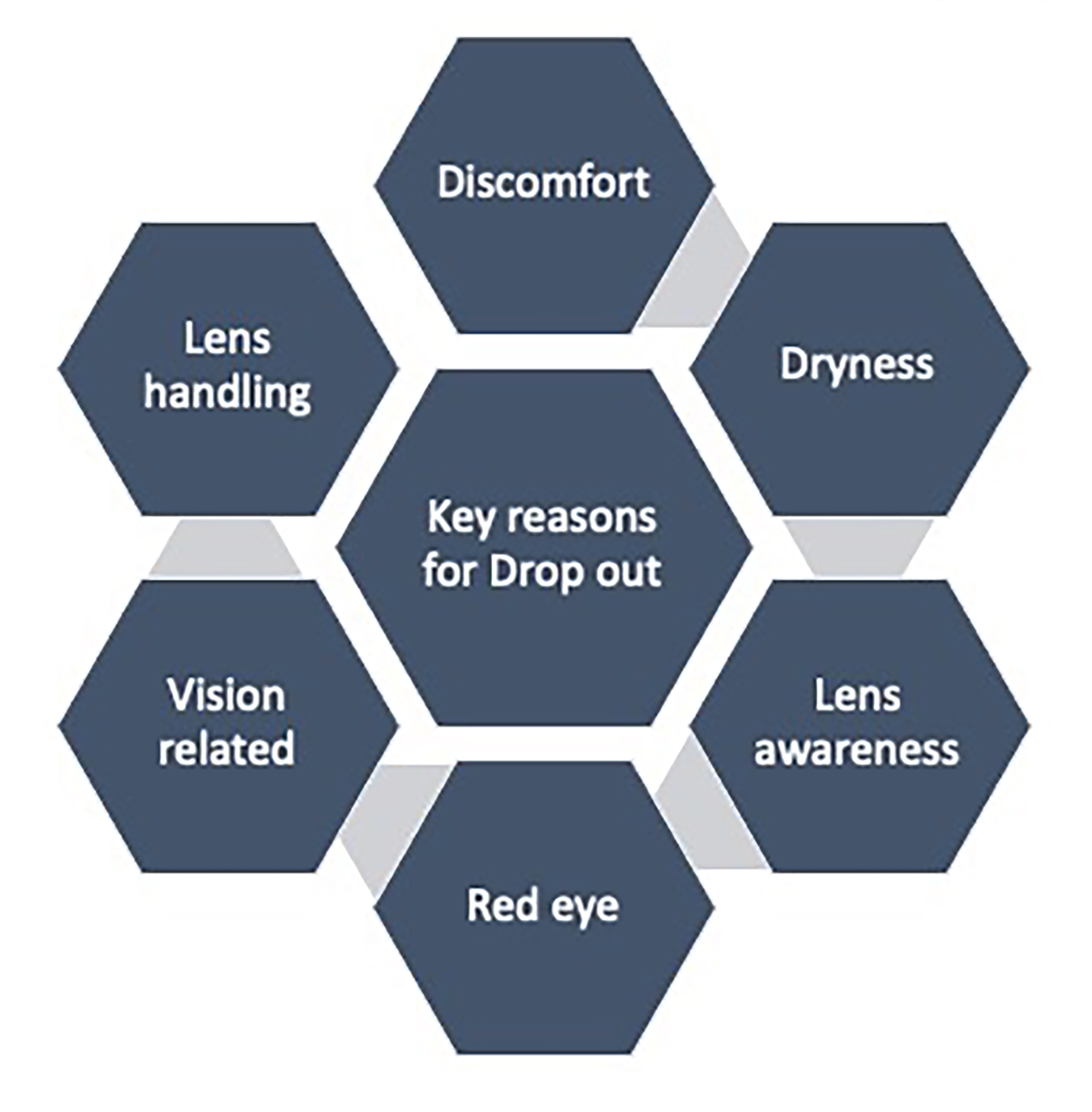

Key reasons for drop out include discomfort, dryness, lens awareness, red eyes, vision-related problems and lens handling (figure 4). Lens handling issues are more common in neophytes than established wearers. Most new wearers who will drop out (25% on average), will cease wear within the first two months. Hence, it is essential to follow up with patients to check how they are getting on and to either have them attend a follow up appointment or/and provide remote support to work on handling skills or (if needed) enhance lens comfort.

Figure 4: Principal reasons for ceasing contact lens wear, adapted from Wolffsohn1

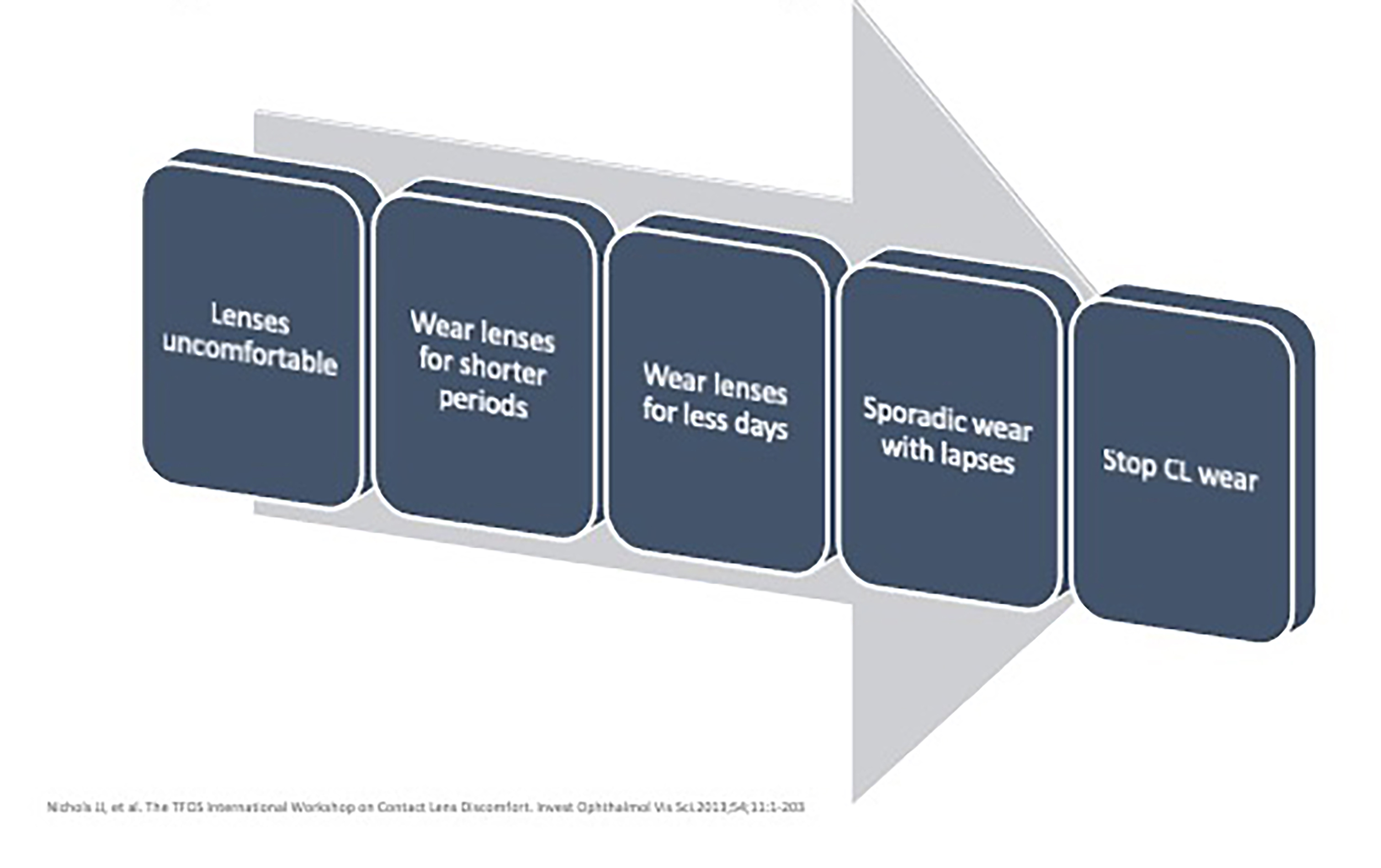

Comfort related issues often underlie the decision to suspend lens wear. Comfort is likely to be multifactorial. Early red flags may include altered wearing habits or comfort rating scores during specific activities (figure 5). A difference in comfortable wearing times vs actual wearing times of two or more hours warrants further investigation.

Figure 5: Progression of wear schedule changes on the pathway to contact lens drop out

Visual-related aspects

Visual quality changes may occur while blinking if there is dry eye, poor lens wettability, deposits, or an ill-fitting lens. Exploring patient reported outcomes with respect to daily tasks can help inform clinical decision making. Vision-related reasons for drop out have been found to be more common among new multifocal and toric lens wearers or those with low prescriptions.

For a toric lens, despite lens markings appearing aligned and stable in the primary position this may not necessarily be the case during tasks involving versional eye movements. For instance, when reversing a car, issues may only become apparent when looking up and sideways in the mirrors. For individuals with contact lenses for presbyopia, real-world functional vision assessments should be considered rather than solely relying on high contrast visual acuity. It is also worth reminding patients and practice staff that a single multifocal design does not work for all individuals and initial lens performance is not indicative of long-term success.

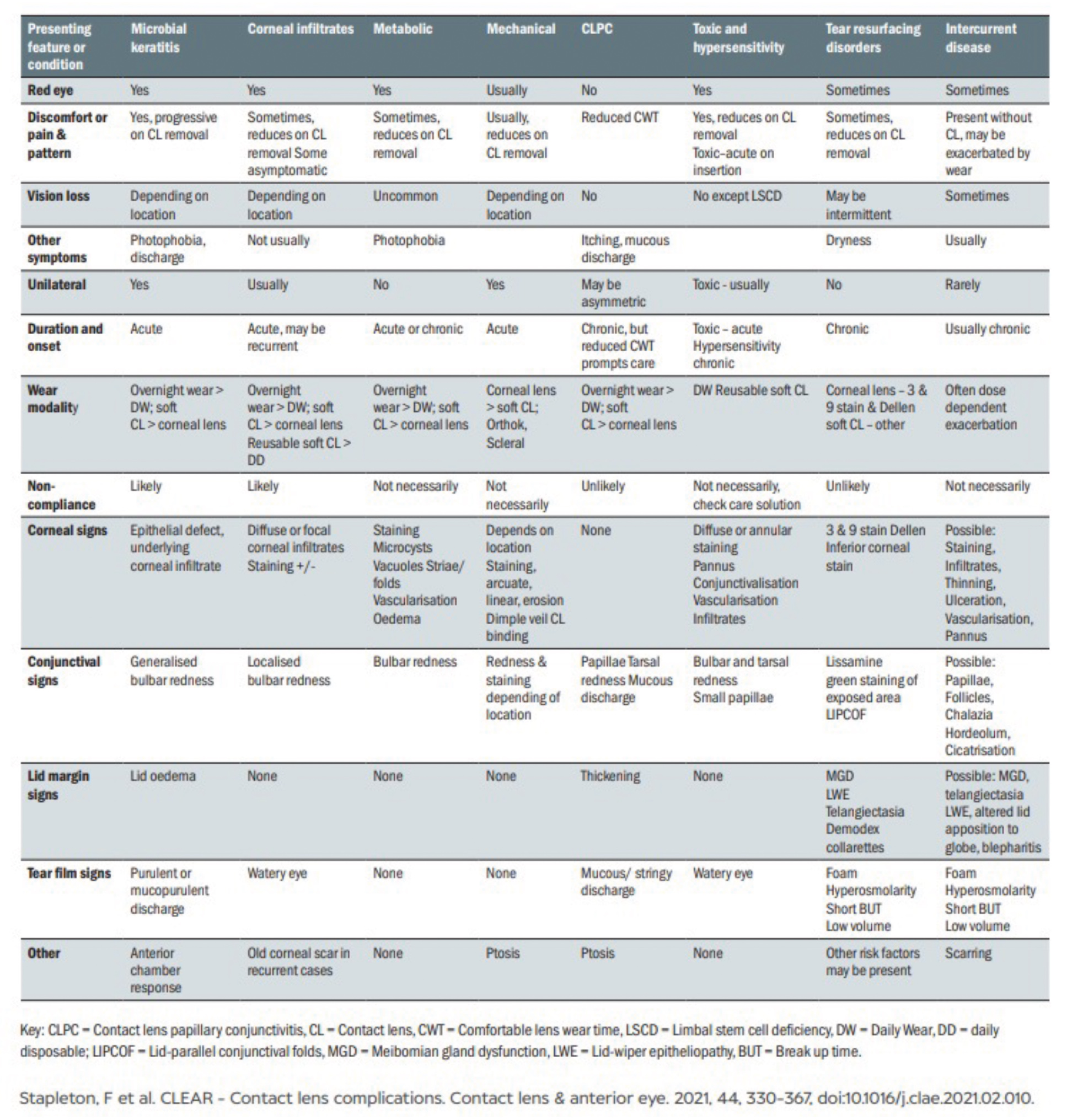

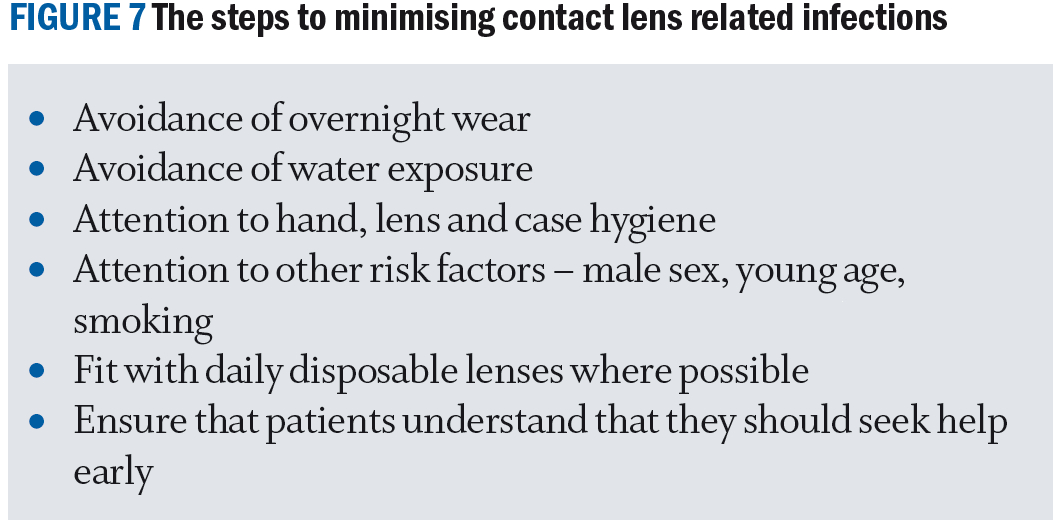

Contact lens complications

Contact lens wear can be safe in compliant wearers. Complications are usually mild and easily managed with intervention, a useful overview is provided in figure 6. Risk factors should be identified, and steps taken to minimise the chance of contact lens related infections (see figure 7).

Figure 6: Overview of contact lens complications, from the complications paper, Stapleton et al4

A proactive approach by both wearer and practice team can ensure success is maximised; at times this may involve a change of lens type, modality, care system or/and management of co-existing ocular pathology to keep pace with the patients’ changing needs. It is unlikely the optimal lens for an individual will remain the same throughout their lifetime.

Contact lenses are medical devices and the importance of having an ECP involved in the contact lens decision making process should not be underestimated. Unregulated purchasing of contact lenses with inappropriate contact lens substitution, has been found to lead to contact lens dissatisfaction and complications, including higher infection rates.

Most soft contact lens properties investigated, except changing back surface design, have been found to potentially impact performance, as illustrated in figure 8.9 Thus, the ECP should play an active role in making recommendations.

Figure 8: Soft contact lens properties found to impact performance.9 The 15 with the red box signifies those where peer-reviewed evidence support is available, and the green box has the one where there to date is a lack of peer-reviewed evidence. Visual courtesy of CORE

Conclusion

The BCLA CLEAR publications provides a global consensus of the published contact lens literature (over 19,000 papers), helping to shape best practice. Through these reports it is clear how some modes of contact lens practice are based on historical concepts and habits rather than evidence. The publications have also been helpful in identifying areas in need of further research in the evolving field of contact lenses. The papers have become a go-to resource, with their impact reflected in over 300 citations and the clinician summaries which are now available in several languages.

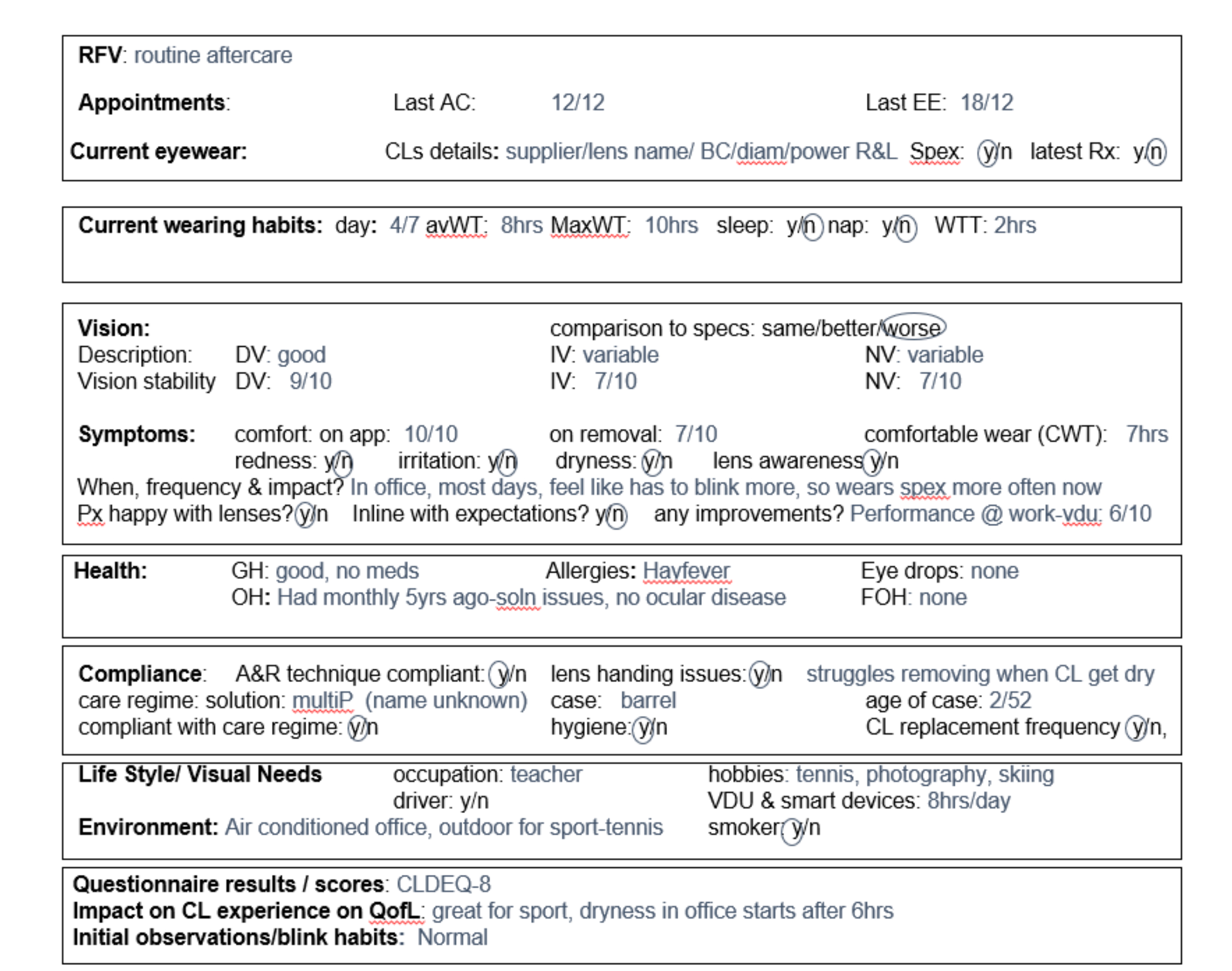

Using the learnings from the BCLA CLEAR publications, we can all make efforts to adopt a more evidence-based approach to contact lens care and good record keeping (see figure 9).

Figure 9: Aftercare record keeping example

Given the benefits contact lenses provide and the diverse range of contact lenses, modalities, and custom-made lenses options available, we should be recommending contact lenses to all suitable patients and promoting the value of ongoing contact lens care. Excitingly there will soon be a similar approach for presbyopia, so look out for the BCLA CLEAR presbyopia publications in 2024 and the associated articles.

- Dr Manbir Nagra is an optometrist, educator and researcher based in the United Kingdom. She works as an independent consultant within the optical sector.

- Neil Retallic is an optometrist with experience of working with in practice, education, industry, and head office roles. He currently works for Specsavers and the College of Optometrists in the United Kingdom and is the Immediate Past President of the British Contact Lens Association.

The editors for this series are Neil Retallic and Dr Debarun Dutta.

- The full report and supplementary information can be accessed at www.contactlensjournal.com/article/S1367-0484(21)00022-9/fulltext

- The BCLA CLEAR Summary report is a short bite-size evidenced-based practical guide for clinicians, bringing together the key findings from the report. Accessed via CLEAR (bcla. org.uk)

- Listen to the BCLA CLEAR Evidence-based contact lens practice podcast

- https://open.spotify.com/episode/ 5iyN9GaFjWWF3D k9A7DQRi

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement and recognition to James Wolffsohn, Kathy Dumbleton, Byki Huntjens, Himal Kandel, Shizuka Koh, Carolina Kunnen, Manbir Nagra, Heiko Pult, Anna Sulley, Marta Vianya-Estopa, Karen Walsh, Stephanie Wond and Fiona Stapleton who were the paper’s authors and the educational grants from Alcon and CooperVision.

Original paper: Wolffsohn, J.S.; Dumbleton, K.; Huntjens, B.; Kandel, H.; Koh, S.; Kunnen, C.M.E.; Nagra, M.; Pult, H.; Sulley, A.L.; Vianya-Estopa, M.; et al. CLEAR - Evidence-based contact lens practice. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association 2021, 44, 368-397, doi:10.1016/j.clae. 2021.02.008.

References

- Wolffsohn JS, Dumbleton K, Huntjens B, Kandel H, Koh S, Kunnen CME, et al. CLEAR - Evidence-based contact lens practice. Contact lens & anterior eye:the journal of the British Contact Lens Association 2021;44(2):368-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2021.02.008.

- Robertson DM, Cavanagh HD. Non-compliance with contact lens wear and care practices: a comparative analysis. Optometry and vision science:official publication of the American Academy of Optometry 2011;88(12):1402-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182333cf9.

- Wolffsohn JS, Ghorbani-Mojarrad N, Vianya-Estopa M, Nagra M, Huntjens B, Terry L, et al. Fast versus gradual adaptation of soft monthly contact lenses in neophyte wearers.

- Stapleton F, Bakkar M, Carnt N, Chalmers R, Vijay AK, Marasini S, et al. CLEAR - Contact lens complications. Contact lens & anterior eye:the journal of the British Contact Lens Association 2021;44(2):330-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2021.02.010.

- Efron N, Morgan PB. Rethinking contact lens aftercare. Clinical & experimental optometry:journal of the Australian Optometrical Association 2017;100(5):411-31. https://doi.org/10.1111/cxo.12588.

- Chen EY, Myung Lee E, Loc-Nguyen A, Frank LA, Parsons Malloy J, Weissman BA. Value of routine evaluation in asymptomatic soft contact lens wearers. Contact lens & anterior eye:the journal of the British Contact Lens Association 2020;43(5):484-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2020.02.014.

- Nichols JJ, Jones L, Nelson JD, Stapleton F, Sullivan DA, Willcox MD, et al. The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: introduction. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2013;54(11):TFOS1-6. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-13195.

- Morgan PB, Murphy PJ, Gifford KL, Gifford P, Golebiowski B, Johnson L, et al. CLEAR - Effect of contact lens materials and designs on the anatomy and physiology of the eye. Contact lens & anterior eye:the journal of the British Contact Lens Association 2021;44(2):192-219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2021.02.006.

- Efron N, Morgan PB, Nichols JJ, Walsh K, Willcox MD, Wolffsohn JS, et al. All soft contact lenses are not created equal. Contact lens & anterior eye:the journal of the British Contact Lens Association 2022;45(2):101515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2021.101515.

- Contact Lens Spectrum - INTERNATIONAL CONTACT LENS PRESCRIBING IN 2022 (clspectrum.com)

- BCLA Website: https://www.bcla.org.uk/Public/Public/Member_Resources/Do_s___Dont_s_Factsheet_of_Contact_Lens_Care.aspx