I saw Adrian when I was supervising a pre-reg optometrist. It was late January 2006 and Adrian was being seen as an emergency in clinic on a Saturday morning. He had flown back from Thailand the night before and his plane had landed at Heathrow at around 1am. I saw him later that day at 11am; I could tell from the look on my pre-reg’s face that things did not look very straightforward clinically.

The presenting complaint was of ‘patchy vision’ and a ‘very bad headache’; Adrian indicated to his brow line and over the vertex part of his head. He had been away on a ‘holiday of a lifetime’; spending two months travelling around some more remote areas of Thailand, finishing his tour with a week on the beach in Phuket before flying home.

Adrian was 35 years old and had just become divorced as well as leaving his job in the City. His lifestyle choices meant that his weight had become an issue, he was smoking around 20 cigarettes a day and drank 12-14 units of alcohol most days. He was not the picture of health. He had not seen a doctor for years, knew his lifestyle was problematic in the long term but was not on any medications.

This was Adrian’s first eye examination and he denied noticing any issues with his eyesight or eyes prior to his flight home. It was during this journey that his vision had suddenly become patchy and the two-day ‘dull but persistent headache’ he had been

ignoring had worsened. He assumed it was the cabin pressure or perhaps a migraine and it was his taxi driver who had collected him from his flight that suggested he saw his ‘optician’ to be reassured.

Adrian had mildly dilated, but normally reactive, pupils and was looking quite ‘glossy’ and feverish and said he felt ‘clammy’. He did not look at all well. His unaided acuities were 6/9 R and L with no refractive error of note. There was no obvious oculomotor imbalance and slit lamp examination of the adnexa and anterior eye was unremarkable other than some early pterygium. He was quite light sensitive on examination and found it all very uncomfortable.

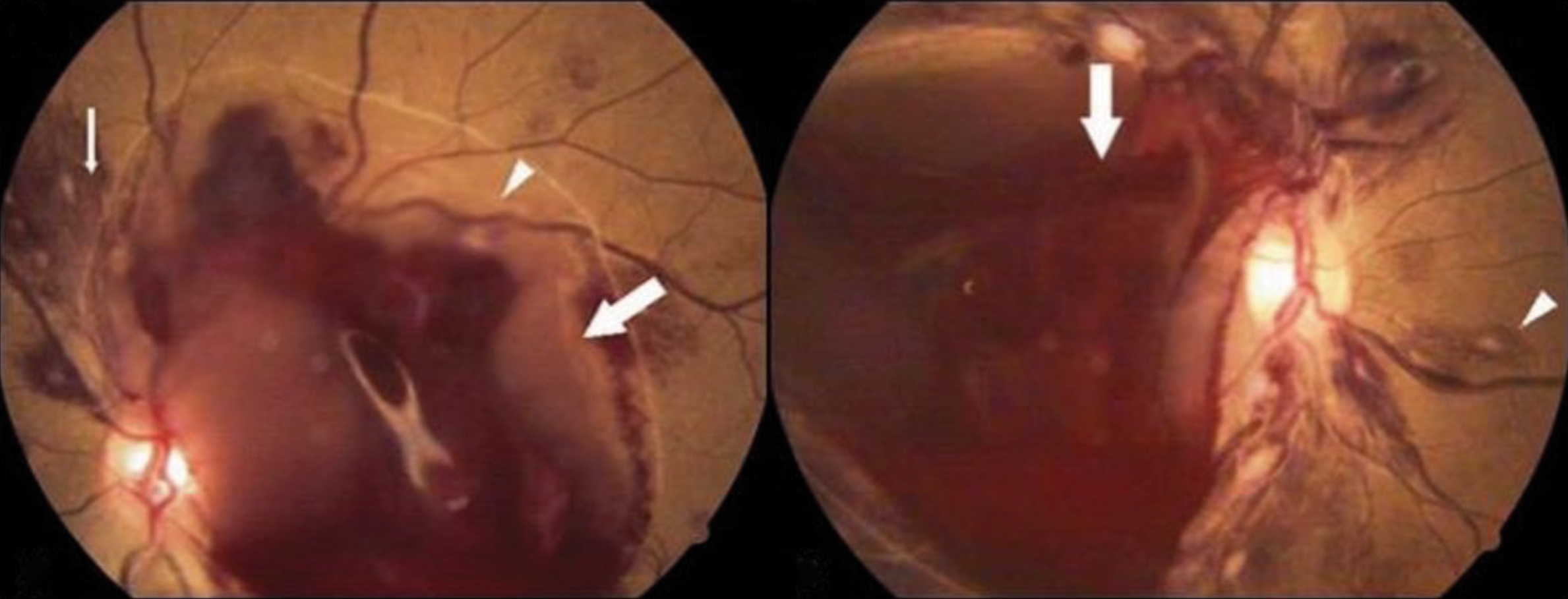

Fundus examination showed some scattered dot and blot haemorrhages throughout both fundi. There were no cotton wool spots or exudates and the maculae were clear. The optic nerve heads were small and the margins were indistinct and hazy and the posterior media was very hazy too. There was gross venous dilation in the right eye close to the optic nerve head. Indirect ophthalmoscopy gave a clearer picture of the mildly raised, congested optic disc margins.

I made the decision to send Adrian straight to the accident and emergency department locally where I later learned that he was admitted in a nearby teaching hospital for three weeks. Approximately four months later, in the early British summer, Adrian returned to the practice to let us know the outcome of his referral and to buy some sunglasses as he was now suffering with a lot of glare issues.

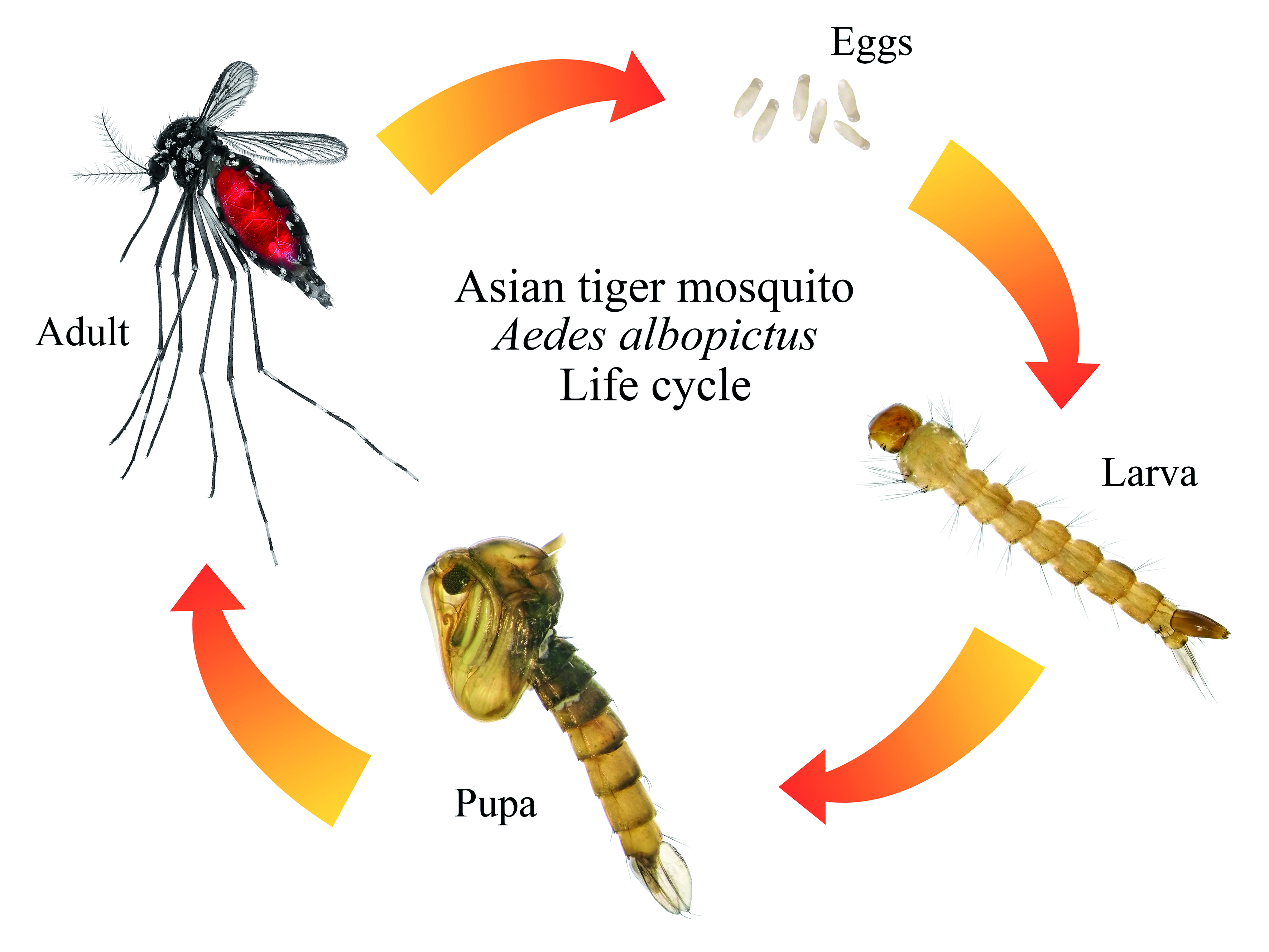

Figure 1: This illustration demonstrates that the female, full of her blood meal will lay thousands of eggs in ‘rafts’ on the surface of still water or singly in drier areas prone to flooding. These rafts hatch within a few days, while the single eggs may lay with dormant embryos until the optimal aquatic conditions occur for hatching. The larvae go through four stages of development before they pupate and emerge as adult insects. The larval and pupal stages of all mosquito species are always aquatic and lasts approximately one to two weeks depending on water conditions and food supply. Rather like other insects that have a pupal stage, such as mayflies, the dorsal pupal carapace splits and the new adult mosquito emerges on to the surface of the water.

I was expecting him to tell me that he was now well on the way to diabetic control and on antihypertensives. However, it was not quite that uncomplicated, my assumption although partially plausible was not the cause of his hospital admission or the ongoing issues.

Adrian had been infected with Japanese encephalitis (JE) while travelling in Thailand. He could not be sure that he had ever received a vaccine for JE, but had not checked before he travelled and he must have been bitten by a mosquito carrying the virus.

His treatment had not been straightforward and his resulting mild brain injury, from his now resolved viral meningeal inflammation and mild hydrocephalus, was causing him some difficulties with photosensitivity. His diagnosis of pre-(type 2) diabetes had been coincidental and a concurrent problem with the JE, but not the cause of his presenting complaint. His primary concern now was how to control his light sensitivity, because despite his recovery, his brain ‘swelling’ had left a legacy of mild, constant photophobia.

Happily, Adrian had also made some sensible lifestyle decisions having been so unwell and had modified his diet, exercise and alcohol intake and was several kilos lighter. He remained under the care of the ophthalmology team until his retinal signs were clear and he has not had any further issues to date to my knowledge.

Clinical Findings due to Japanese Encephalitis

Adrian was unfortunate to have contracted JE virus. He was fortunate, however, that his early symptoms occurred on the plane on the way home and that he sought prompt advice. Early physical signs of infection are dizziness, fever, nausea or vomiting, headache, light sensitivity, sound sensitivity and later motor disorders, neck stiffness, seizure and loss of consciousness in severe cases.

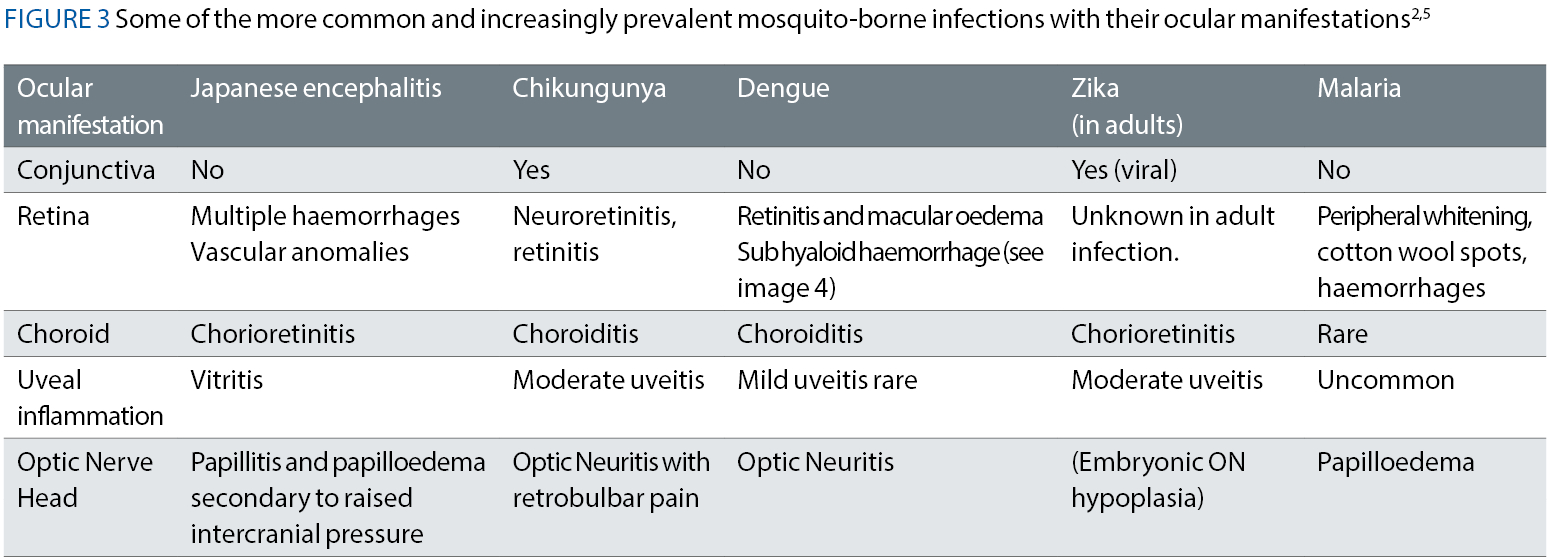

Ocular signs from JE infection vary from case to case and do not appear to be well documented. However, literature searches agree that the signs tend to be restricted to the posterior pole with vitritis, multiple retinal haemorrhages similar to early stage 1 diabetic retinopathy, vascular changes – similar to hypertensive venous dilation, papillitis and papilloedema – again, easily mistaken for hypertension. Progression of ocular symptoms can extend to the adnexa and lead to 6th (abducens) nerve palsy, 7th (facial) nerve palsy and also cortical blindness.

Treatment

Diagnosis of viral encephalitis is made via lumbar puncture to test the cerebrospinal fluid for specific IgM antibodies. There is no treatment for JE and in severe cases, hospitalisation is required for diagnosis, fluid resuscitation, rest and pain relief to allow the body to combat the infection. Avoidance is the best line of action, with vaccination, mosquito control, chemical repellents as well as mosquito netting and covering up exposed areas on the body to mitigate being bitten.

Vector infection: Mosquitos require water to breed; stagnant pools, freshwater floodplains, saltwater marshes, containers with puddles – anywhere there is standing water. They are more prevalent in countries with high humidity, and it has been suggested that global warming has contributed to the spread of these vectors into parts of Europe. Many species of mosquito have evolved to be able to breed in sporadic flood pools or artificial pools other than rainwater.

While we find mosquitos in Europe somewhat irritating, they play an important part in the food chain and are good for the environment. Male mosquitos have a short lifecycle and are chiefly pollinators. They will congregate around breeding grounds and food sources with the primary goal of reproducing the species. Females have a longer life span and may live up to six weeks or more in the right conditions.

They are not pollinators and it is the female mosquitos who feed on blood. Not all mosquitos are the same, there are estimated to be over 3,500 species, of which over 100 are known to infect humans. Infections can either be bacterial pathogens, viruses, filarial infestations or parasitic. Blood, whatever the source, provides sufficient nutrients for egg production.

It is in the process of feeding from host to host that the vector borne viruses and infections are spread by mosquitos. Many infections can live in the mosquito gut, unaffected by the saliva and it is during the process of the mosquito feeding/biting, when blood is drawn from the host that infected saliva is left behind. It is the bodily reaction to this saliva that makes the itchy, inflamed bumps on our skin after a mosquito has feasted on us. Not all viruses can live in the saliva of a mosquito, and it is believed that this is why diseases such as HIV, hepatitis and herpetic infections are not spread by mosquitos.

Discussion

Foreign travel is such a part of our lives in the 21st century. We may think nothing of taking holidays often and overseas in search of some winter sun or better weather. Although rare, mosquito-borne infections are globally on the rise and it is important to consider recent foreign travel when presented with a case such as Adrian’s. What might initially appear to be a diabetic fundus in a patient with a higher than optimal BMI for his age, should not be a lone consideration, despite the lifestyle choices pointing to raised blood sugars.

Figure 4: Dengue Virus haemorrhagic retinopathy. Mil Med, Volume 183, Issue suppl_1, March-April 2018, Pages 450–458, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usx183

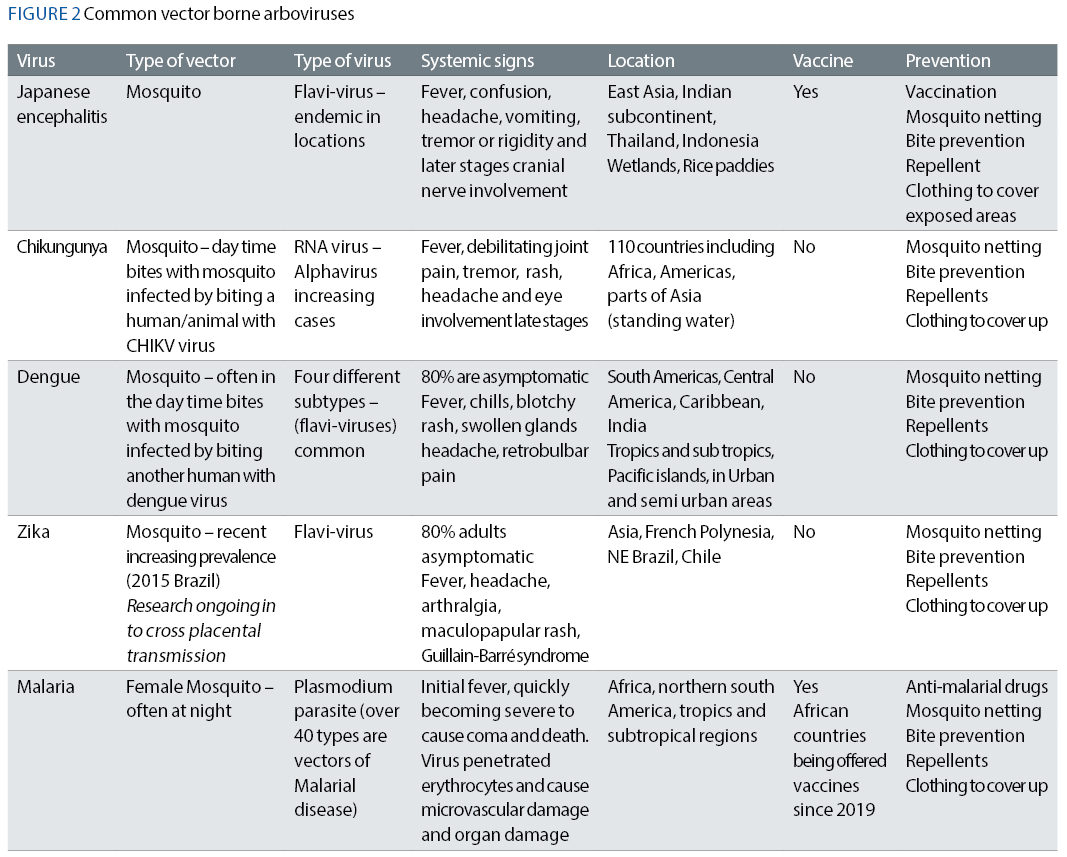

The news stories in the past five years have documented increased risk of other mosquito-related diseases, and of those seen in peak ‘winter sun’ holiday spots, Zika, dengue, chikungunya, Japanese encephalitis and malaria are some of the most prevalent and their global spread is increasing throughout Africa, South and North America, the Caribbean and some parts of Europe as well as Asia.

While some have vaccines or oral preventative medications to minimise risk of infection, such as malaria and Japanese encephalitis, there is still no treatment for Zika, chikungunya or dengue at time of writing. Avoiding being bitten is the best protection. Although rare, new strains of Japanese encephalitis have been found and continuous global surveillance is ongoing to develop de-novo vaccines.

Due to the significant mortality and morbidity secondary to this vector-borne infection, vaccinations for travel and in risk populations are vital. Adrian did have the classic retinal haemorrhages, very similar in appearance to stage 1 diabetic retinopathy accompanied by papillitis and vitritis. He luckily did not go on to present with any cranial nerve palsy or visual-cortical involvement.

For the clinician, it is important to consider risk with unusual presentations where there has been foreign travel and seek further medical opinion swiftly to allow for diagnosis and an intervention at the earliest stages.

- Sarah graduated from City University in 1993. Her work has taken her from sub-Saharan Africa to the Hospital Eye Service, academia and independent practices in Devon and for the last 25 years in Hampshire. She is involved in the sight loss sector, presenting training and patient-facing content for those living with sight loss and their colleagues and families. Sarah is currently on sabbatical, working closely with support services for those with visual impairment.

References

- James W Karesh, Robert A Mazzoli, Shannon K Heintz, Ocular manifestations of mosquito-transmitted diseases; Military Medicine, Volume 183, supp 1, p450-458 March-April 2018; https://academic.oup.com/milmed/article/183/suppl_1/450/4960044

- Singh S, Kumar A. Ocular Manifestations of Emerging Flaviviruses and the Blood-Retinal Barrier. Viruses. 2018 Sep 28;10(10):530. doi: 10.3390/v10100530. Erratum in: Viruses. 2019 May 24;11(5): PMID: 30274199; PMCID: PMC6213219. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6213219/ 3. WHO Fact Sheet; Japanese Encephalitis, January 2019; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/japanese-encephalitis#:~:text=Permanent%20neurologic%20or%20psychiatric%20sequelae,no%20cure%20for%20the%20disease

- Suman V, Roy U, Panwar A, Raizada A. Japanese Encephalitis Complicated with Obstructive Hydrocephalus. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Feb;10(2):OD18-20. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16917.7274. Epub 2016 Feb 1. PMID: 27042509; PMCID: PMC4800575.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4800575/

- de Andrade, GC, Ventura, CV, Mello Filho, PAd. et al. Arboviruses and the eye. Int J Retin Vitr 3, 4 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40942-016-0057-4

- Maude RJ, Dondorp AM, Abu Sayeed A, Day NP, White NJ, Beare NA. The eye in cerebral malaria: what can it teach us? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009 Jul;103(7):661-4. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.11.003. Epub 2008 Dec 18. PMID: 19100590; PMCID: PMC2700878. 7. WHO FACTSHEETS: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chikungunyahttps://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/dengue-monthly

- Images Fig 4: Mil Med, Volume 183, Issue suppl_1, March-April 2018, Pages 450–458, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usx183

- Mukhopadhyay, K, Sengupta, M, Misra, SC. et al. Trends in emerging vector-borne viral infections and their outcome in children over two decades. Pediatr Res (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02866-x

- Illustration figure 1: https://hawxpestcontrol.com/the-life-cycle-of-mosquitoes