The word triage originates in the French language from the word ‘trier’ which means ‘to separate out’. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word as ‘the preliminary assessment of patients or casualties in order to determine the urgency of their need for treatment and the nature of treatment required’, and this is thought to date back to the First World War, with reference to the military system of assessing the wounded on the battlefield.

Often triage can be categorised, especially in dangerous or acute settings such as a busy hospital accident and emergency department with patients being prioritised according to their needs – it is generally accepted that there are three categories of triage:1

- Category 1: Immediate treatment

- Category 2: Urgent treatment

- Category 3: Non-urgent treatment/routine treatment

While most optical professionals and their support staff rarely operate in dangerous or acute settings, effective triage is of the utmost importance to enable patients to receive the right treatment, in the right place at the right time. Some presentations to optical practices may seem mundane, however, some may be full-blown ocular emergencies, which could potentially be sight-threatening and need to be treated or referred to another specialist or hospital department.

Even with the advent of many more independent prescribing (IP) optometrists in the community, patients may not always be able to be treated and retained within optical practice and may need urgent referral to ophthalmology depending on their presentation.

Current UK national and local protocols should always be considered when making any referral, it is the responsibility of the optometrist or dispensing optician to ensure they are fully conversant and up to date with protocols relevant to the location where they practice. The College of Optometrists Annex 4 Urgency of referrals table provides guidance on which conditions are considered an emergency or urgent.2

All General Optical Council (GOC) registrants, whether they be optometrists, dispensing opticians, contact lens opticians or low vision opticians all have a duty of care to their patients and duty to refer patients to an appropriate professional with the appropriate qualifications and registration who can administer the care they require.3

Often in optical practice, however, it is not the optometrist or the dispensing optician who is the first point of contact – often it will be a receptionist who answers the telephone to a distraught patient or greets them at the reception desk in practice. This said, it is vitally important that all practice staff are trained to recognise ‘red flags’ they can see and key phrases that patients may describe to efficiently deal with them.

Most new patients seen in the hospital eye service (HES) originate from optometrist referrals,4 with numbers that have been increasing since the 1980s; the last published data found was by Davey et al (2010)5 where 72% of referrals into the HES originate from community optometrists and 28% from general practice.

Working to the standards of practice laid down by the GOC, optometrists and dispensing opticians work within their scope of practice and refer on any patient deemed necessary.4 In a quantitative systematic review of optometrists’ referral accuracy and the contributing factors Carmichael et al (2023)4 found significant variation in reported referral accuracy both within and across different ocular conditions.

This in turn places a burden on busy NHS ophthalmology clinics, however, patients have the right to receive the right care at the right time in the right setting.

First port of call

Most community optical practices will at some point during their lifespan experience a broad variety of conditions that patients can walk through the door with on any given day. This can often make for an interesting and challenging day for practice teams including everyone from receptionists, administrators, optical and clinical assistants to registrant members of staff.

Optical practices who offer NHS services in each of the devolved nations will likely have some sort of ‘emergency’ eye care scheme in place. They may be called different things in different nations, even in different regions within a nation.

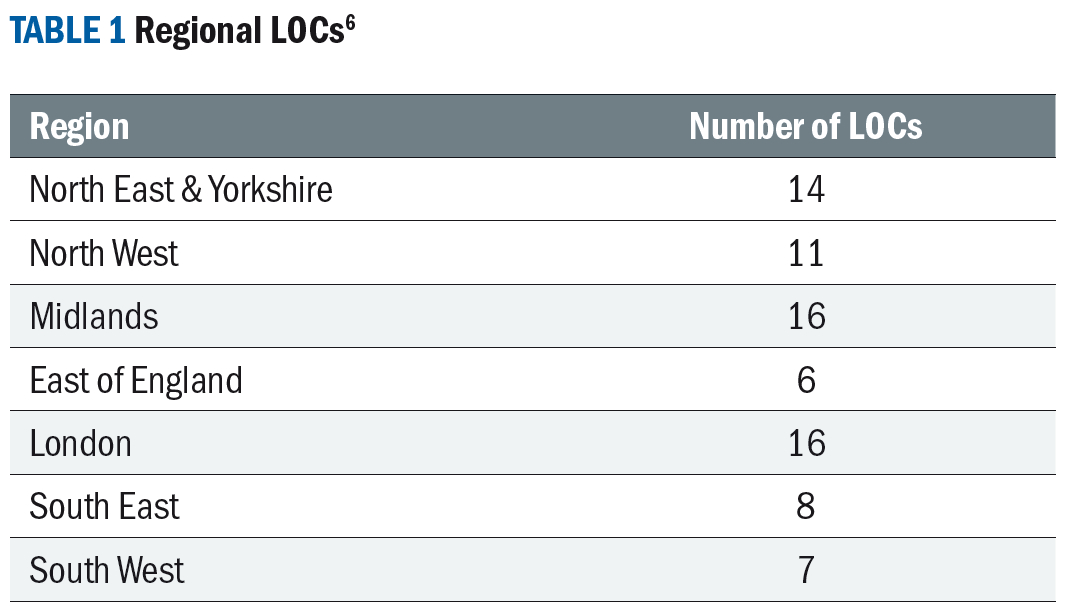

Local Optical Committee Support Unit (LOCSU) provides 12 different clinical service pathways, with over 74 different LOCs in England6 each responsible for negotiating optical services with local healthcare commissioners resulting in a postcode lottery of available services depending upon where you live, leading to healthcare inequalities (see table 1).

Common examples in England are:

- MECS: Minor Eye Conditions Services – defined by Primary Eyecare7 (who are the largest single not for profit primary eye care lead provider in England. Primary Eyecare contracts with NHS commissioners and trusts to make NHS-funded eye care services available from local eye care practices, from small independent practices to large national chains. It is an optometry federation that aims to support patients by broadening the eye care services available from local opticians.) As a service providing assessment and treatment for people with recently occurring minor eye problems. It is an NHS service provided by accredited optometrists (and in some areas specialist contact lens opticians).

- CUES: Community Urgent Eyecare Services – defined by Primary Eyecare as a service that provides urgent assessment, treatment, or referral for sudden onset eye problems such as flashes, floaters, vision loss or minor eye injuries.8

In Northern Ireland, the scheme is called:

- NI PEARS: Primary Eyecare Assessment and Referral Scheme ¬ defined by Optometry Northern Ireland9 as a service provided by most optometry practices across Northern Ireland for patients who develop a sudden eye problem.

In Wales, following recent legislative changes there is a move to a nationally commissioned unified system rather than locally commissioned with Wales General Ophthalmic Services (WGOS) replacing the General Ophthalmic Services (Wales) (GOS[W]).WGOS provides a tiered eye care service:10

- WGOS1 – sight test with prevention and wellbeing creating a patient specific management plan (fee £43.00 compared to England NHS sight test fee £23.24)

- WGOS2 – eye care completed in primary care,

Band 1: Acute eye care services completed in primary care.

Band 2: Further examination to inform or prevent referral.

Band 3: Follow up to Band 1 and post cataract assessment.

- WGOS 3 – optical and non-optical aids, holistic rehabilitation, advice to access local low vision service. WGOS 3 includes Certification of Vision Impairment (CVI(W)).

- WGOS4 – Enhanced assessment as part of an agreed referral refinement or monitoring pathway allowing patients to be managed in primary care instead of being referred into the HES.

- WGOS 5 – provision of eye care by an IP optometrist/OMP to treat and monitor patients in primary care avoiding referral into the HES.

- WGOS Optical Vouchers – provision of optical appliances.

Scotland was the first to set up a nationally commissioned eye care scheme with any eye-related issue being seen in the first instance by a community optical practice. General Ophthalmic services delivered in the community by NHS practices can see patients for routine eye examinations and acute presentations and will often deliver shared care schemes in conjunction with secondary care (NHS hospital ophthalmology departments).11,12

By enabling patients to be seen in the community reduces the burden on NHS secondary care and often care is delivered in a familiar setting, by known practitioners, which can be a big positive for anxious patients. The GOC commissioned a public perceptions survey in 2015 and again in 2021 whereby they asked around 2,000 members of the public who would visit an optometrist as their first port of call for an ocular issue.

The numbers have increased significantly in recent years – from one in five respondents in 201513 to one in three respondents in 2021.14 In November 2023, the Clinical Council for Eye health Commissioning announced the new Eye Care Support Pathway15 in November to improve the experience of patients across the UK highlighting people’s needs at four key stages:

- Having an initial appointment

- Having a diagnosis

- Support after a diagnosis

- Living well with my diagnosis

This pathway has been developed in partnership with health and social care professionals across the sector.

Equipping the practice team

As with any new skill, it takes time to learn how to do new things, very few people possess the inherent skills and will require some training to enable them to master a new skill and learning how to triage patients presenting in optical practice is no different.

Many optical practices hold regular staff meetings and training sessions and deliver ‘on the job’ training for reception and non-registrant staff. Often an optical practice has a training lead or ‘champion’ who will be responsible for delivering and monitoring ongoing training and development, others will enrol staff on recognised training schemes or hold a training session within their practice to enable staff obtain the necessary skills to triage effectively.

Regardless of how any optical practice approaches staff training, one theme will be common across all modalities of training – the key information required to enable a registrant optician, especially optometrists – come to a decision about how soon the patient needs to be seen by an eye care professional to enable a favourable outcome will follow a similar pattern or be the same.

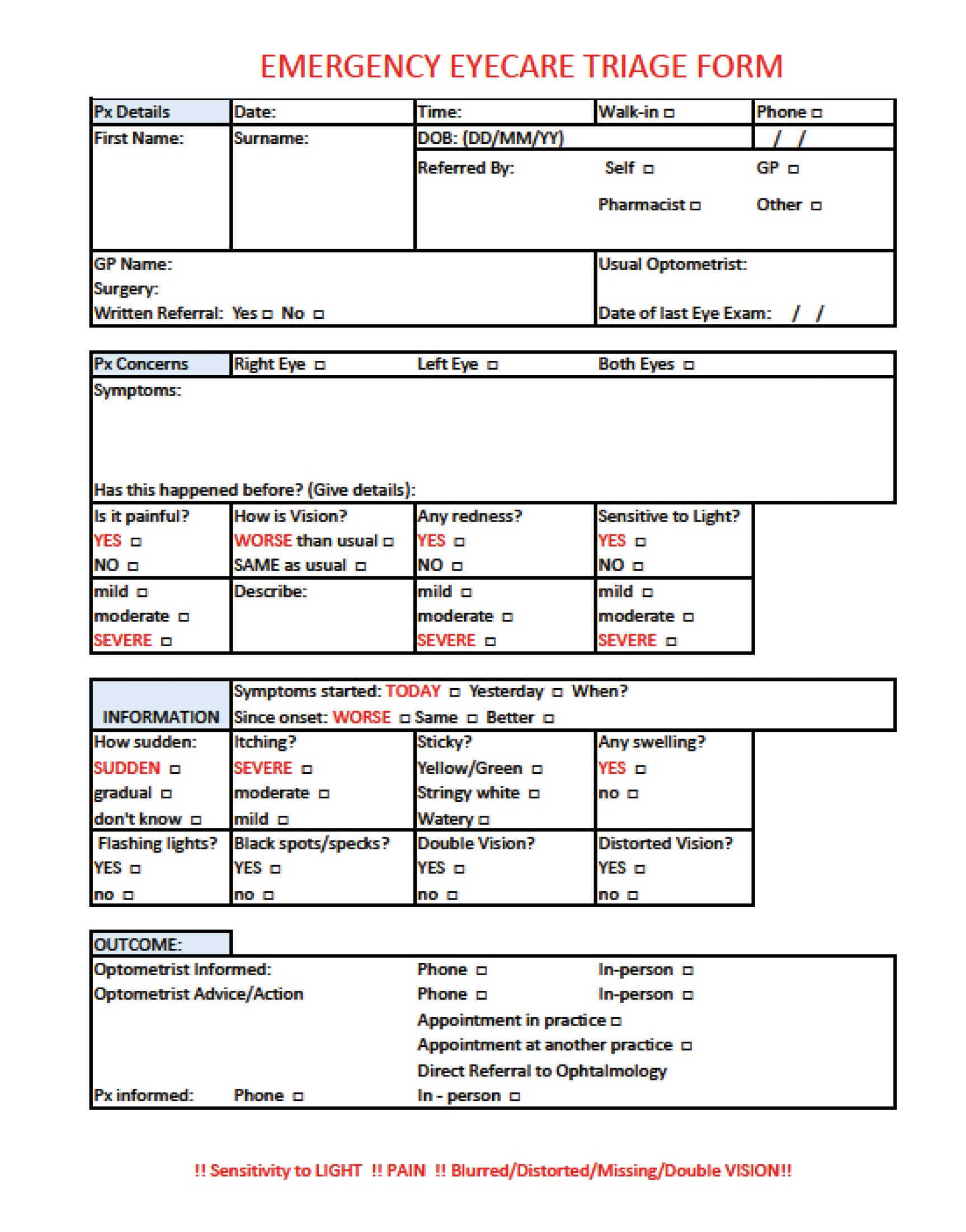

Some practices will employ a very efficient computer-generated triage information gathering template form which can be filled in by the receiving member of staff and then pass on to the optometrist/dispensing optician or MECS accredited Contact Lens Optician for review. Many practices will have these forms in paper form and they will be completed in the same way and passed on appropriately for appraisal by the optometrist and course of action decided.

Several of the optical professional bodies have triage template forms available to download to their members. The government bodies in each of the devolved nations of the UK also have templates available to optical practices to use.

Figure 1 is an example of a triage form that may be used in optical practice; it serves as a great ‘aide-memoire’ to ensure whoever is dealing with the telephone call or walk-in patient to ask all the relevant questions to ensure as much information as possible is uncovered.

Figure 1: Emergency eye care triage form

Often, if a patient is in extreme discomfort, is anxious or frightened they may omit critical details, which could be crucial in determining the correct course of action. If the person dealing with them can reassure them that they will make a note of all their symptoms and pass this on to a suitably qualified colleague, then this is often enough to calm the patient down and give them the reassurance they need.

Often, if a patient is in extreme discomfort, is anxious or frightened they may omit critical details, which could be crucial in determining the correct course of action. If the person dealing with them can reassure them that they will make a note of all their symptoms and pass this on to a suitably qualified colleague, then this is often enough to calm the patient down and give them the reassurance they need.

It is also important to stress that non-registrant team members should be clear in their conversation with the patient that they will gather the information and pass on to a colleague – they should offer no diagnosis but should act as the conduit between the patient and the eye care professional.

It is also to be noted that all GOC registrant staff have a duty of care to patients to enable them to receive the right care,16 if a practice does not have an optometrist on the premises, they may be on lunch or on holiday, then a dispensing optician who is a GOC registrant is bound by the same standards of practice and must act in an appropriate manner to help any patients with an emergency eye care issue. If the patient needs to be referred out with the practice, then the dispensing optician must attend to this.

The layout of this triage template starts with the more general information we would require in optical practice then concentrates on the emergency presentation – key information is highlighted in red, which draws attention to the potentially more serious aspects of the potential consultation. It is generally accepted that the more sudden in onset, the more painful and if there is loss of vision the more serious the presentation may be and will need swift action.

It is also important to note that at the end there is an outcomes box – this is the initial course of action that the eye care practitioner decides upon. The optometrist may decide to call the patient to receive more information, if their diary permits, they may see the person themselves in person, if there are no appointments available, they may refer to another community optometrist, an optometrist with an IP qualification or depending on the severity of the case they may refer directly to the local ophthalmology department or accident and emergency.

All staff involved in triage must be aware of potentially sight threatening or even life threatening red flags therefore it is essential that on-going training is conducted and systematic review of triage events so that all staff members registrants and non-registrants are fully supported.

Protocol for every situation should also be kept under review to ensure the best possible outcome for every patient. For a triage system to work efficiently it is essential that all of the optical team work collaboratively and all patient records are fully updated as well as a copy of the triage form is retained so it is accessible for all those involved in the patient’s care.

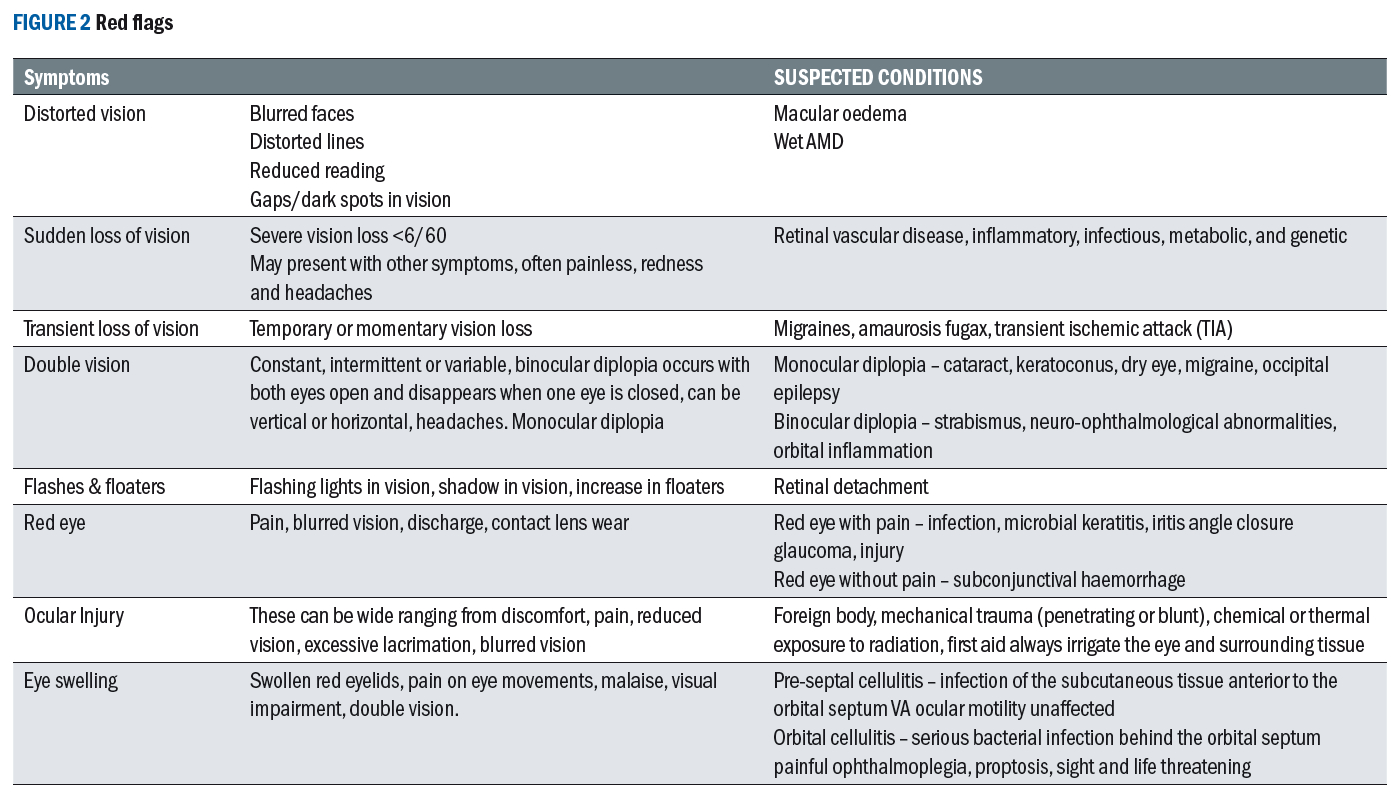

Red Flags: A short summary is included as it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss each condition in detail (see figure 2).

Sudden loss of vision: Always a red flag, this may present as painless, which could be caused by retinal detachment, retinal vascular occlusion, stroke, giant cell arteritis (GCA) usually presents with temporal or occipital pain as well as jaw claudication and fatigue. While this is not routinely seen in community practice numbers investigated for GCA in the UK are growing.17

During the Covid-19 pandemic years 2020-21 in Bath, incidence was found to be significantly higher18 and earlier this year the Royal College of Ophthalmologists highlighted more than one third of NHS hospitals in England lacked a formal clinical pathway for GCA.19

Sudden painful loss of vision can be caused by conditions like acute anterior uveitis, acute angle closure glaucoma and infective keratitis, which also falls under the ‘red eye’ presentation. Double vision: Monocular diplopia can be caused by keratoconus, dry eyes, cataracts or poorly centred intraocular lenses.

Binocular diplopia can be due to strabismus but when of sudden onset can indicate neuro-ophthalmological abnormalities or orbital inflammation with lesions of the cranial ocular motor nuclei of the III, IV and VI cranial nerves. The upper eyelid is elevated by the levator palpebrae superioris, which is innervated by the cranial nerve III so practitioners should also be alerted to sudden onset of ptosis and signs of Horner’s syndrome.20

Veil or curtain: A veil coming across vision and flashes and floaters are linked to suspected retinal detachment. Maclsaac et al (2021)21 found posterior vitreous detachment accounted for the most number of cases over one month seen by hospital eye casualty diagnosed from optometrist referral.

Distorted vision: Wet, neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) can lead to visual impairment if not treated promptly, most patients treated with intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) can stabilise visual acuity but continuous treatment is required as long as the condition is active.22

Ocular trauma: Blunt or penetrating trauma, depending upon injury type, may require intervention by a multidisciplinary team requiring emergency referral. Chemical eye injury requires immediate emergency referral as this can not only be sight-threatening but also life-threatening as the patient may have inhaled/ingested the chemical as well, Ghosh et al (2019)23 found an estimated annual incidence for acute chemical eye injuries in the UK at 5.6 cases per 100,000 population of which 60% were male. Thorough irrigation should always be conducted as part of first aid protocol.

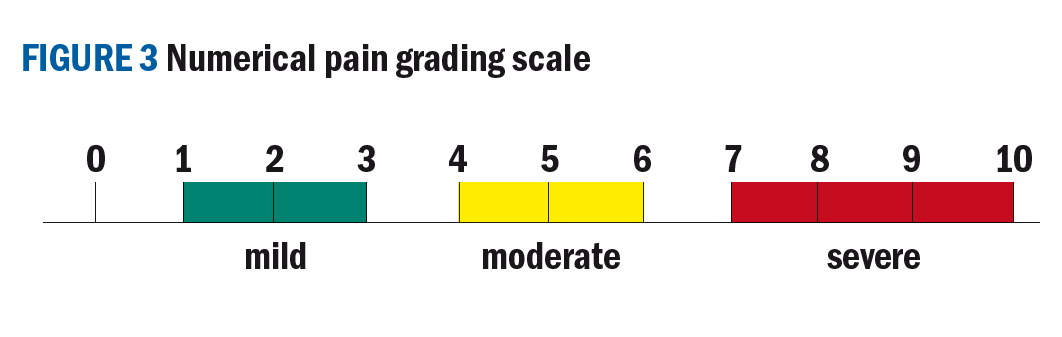

Pain: This is a key indicator and the question on the triage form ‘is it painful?’ is a simple yes or no answer and when yes, asking, does it keep you awake at night? As well as scoring/grading pain provides additional information a simple 0-10 numerical system is easy to interpret (see figure 3) using none, mild, moderate and severe categories, which can help determine urgency of the referral. Acute angle closure glaucoma is likely to cause ‘severe’ pain, to the extent of vomiting and haloes around lights.

A sudden loss of vision is always a red flag any additional symptoms like pain must also be considered.

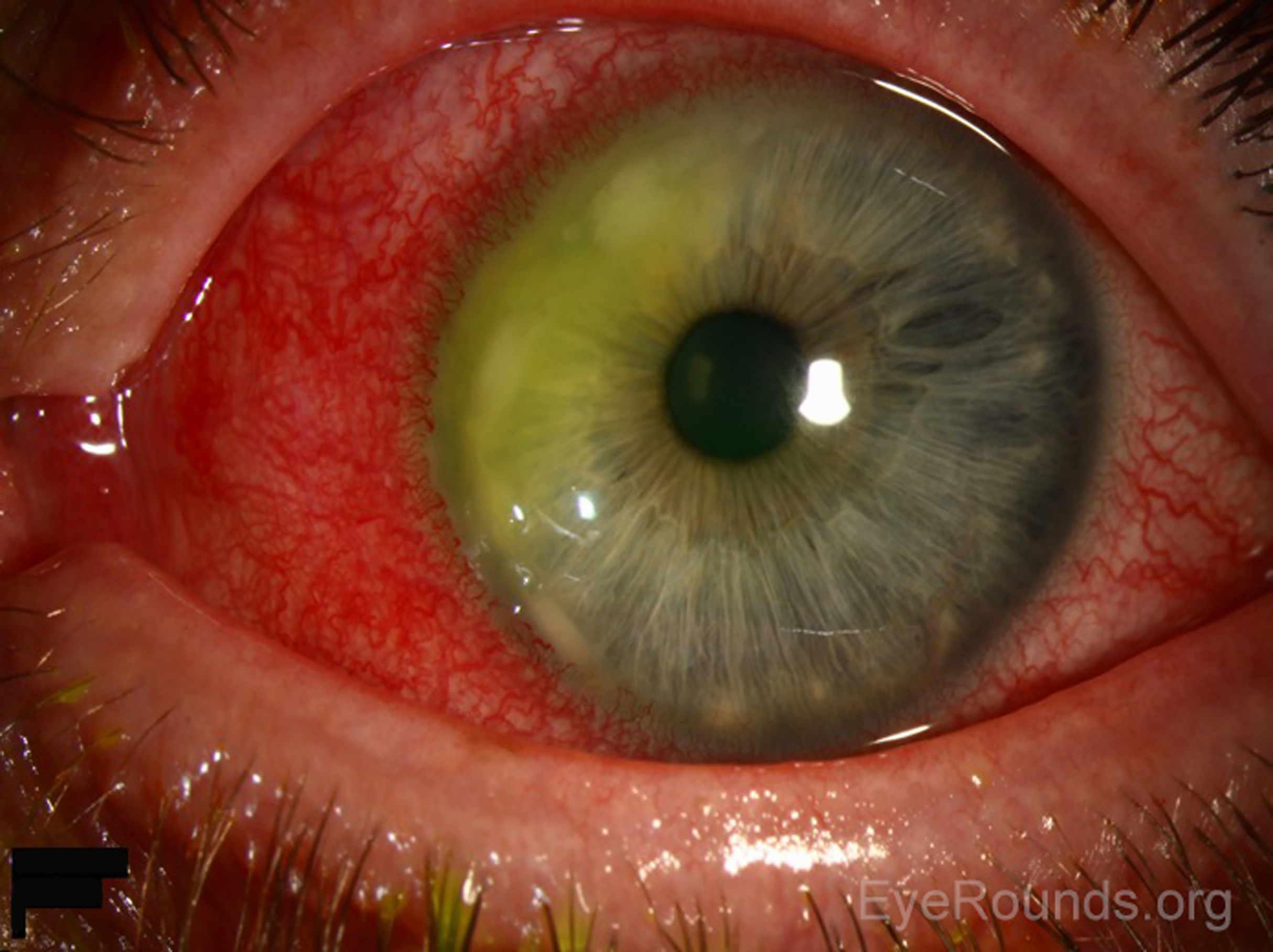

Red eye: Possible conditions that may present with pain could be anterior uveitis or microbial keratitis. Infectious keratitis incidence of 6.96 per 100,000 population/year was found from a retrospective study between 2015-20 in the East of England.24

Red flag – painful red eye indicates possible microbial keratitis

Image: eyerounds.org

Contact lens wear presents an additional risk factor for microbial keratitis therefore in red eye incidents the patient should always be asked if they wear contact lenses and their modality of wear, Stapleton (2020)25 found two to five per 10,000 wearers per year were affected.

Red eye without pain can be as a result of a subconjunctival haemorrhage, which is usually not serious but it is essential to rule out trauma. If the patient has experienced recent trauma then the extent of the subconjunctival haemorrhage must be checked if it extends far back and the posterior border is not visible then there is a possibility of orbital fracture, which would require immediate urgent referral.

Previous surgery: Always ask if there has been any recent ocular surgery or intravitreal injection as there is an increased risk of endophthalmitis or retinal detachment.

Many shared care schemes between primary and secondary care have resulted in a much closer working relationship between optical practices in the community and local ophthalmology departments, indeed, many systems are in place that practices can call a special number to reach the local ophthalmology out patients and speak with an ophthalmic nurse who will contact the on call ophthalmologist via a Clinical Decision Unit (CDU) and decide on the best course of action for any given patient.

Similarly, many hospitals also offer access to the ophthalmology team via email and an ‘eye advice’ portal, which is monitored by staff in ophthalmology and replies to queries from community optometry are answered often in timescales of 30 minutes to a couple of hours. This can be helpful when patients are being managed, treated or monitored in the community, often by an IP optometrist, it gives an extra layer of support without wasting valuable time or resources on outpatient appointments.

Community Eye care

The importance of effective triage should not be underplayed. Clear, succinct, legible information gathered from the patient, presented to the clinician in a timely manner makes for a better patient journey and, more importantly, minimising delays potentially minimises the risk of poorer outcomes and potentially saving someone’s sight.

The Scottish Government in 2021 states: ‘In 2016-17 alone, community eye care in Scotland saved the national health service £71 million through carrying out 1.8 million primary eye examinations. Importantly, in 2016-17 community optometry services preventing more than 370,000 people from having to attend hospital for eye issues.’26

Treating patients in the community allows them to be treated by suitably qualified professionals, often the practice they attend for routine eye care, they are in an environment they feel comfortable and reduces travel and anxiety of travelling to a busy hospital to receive care.

Coupled with this, treating patients in a community setting is less expensive than in a hospital setting. The difference between the two appointments in cost is approximately £120 in a hospital setting27 and between £30-70 in a community setting.

When we add in the number of appointments ‘wasted’ by patients failing to attend then there is a huge cost to the NHS. Many more services could be offered by utilising the money saved by reducing the ‘fail to attend’ rate and by keeping many ocular conditions in the community.

Conclusion

Triage is a fundamental part of community eye care services, and while we may not triage a sight-threatening eye condition every day, practices throughout the country should be able to deal with whatever presents itself. Having well trained teams of support staff who can act swiftly and professionally when an ocular emergency presents makes for better outcomes for the patient.

Optometrists and dispensing opticians are highly skilled practitioners and are trained to investigate, treat and monitor a variety of eye care issues. Many practices now also have IP optometrists who have prescribing rights and this wider enhances the range of conditions that can be managed in a community setting, which is often much more acceptable to patients and reduces the burden on our overstretched NHS ophthalmology departments.

- Fiona Anderson BSc(Hons) FBDO R SMC(Tech) FEAOO is past president of the International Opticians Association, ABDO past president, past chair Optical Confederation, Optometry Scotland member, past Grampian AOC member, EAOO – co-opted trustee, ECOO European Qualifications board member, Renter Warden: Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers, Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers Liveryman & Fellow of the European Academy of Optometry & Optics.

References

- Lam RP, Kwok SL, Chaang VK, Chen L. et al. Performance of a three-level triage scale in live triage encounters in an emergency department in Hong Kong. International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020; 13(28). doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00288-8

- The College of Optometrists. Guidance for Professional Practice Annex 4 Urgency of Referrals Table. Available from: www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/guidance/guidance-annexes/annex-4-urgency-of-referrals-table

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. 10.3 Work Collaboratively with Colleagues in the interests of patients. London. General Optical Council. 2016. P.15

- Shah R, Edgar DF, Khatoon A, Hobby A, Referrals from community optometrists to the hospital eye service in Scotland and England. Eye. 2022; 36. doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01728-2

- Davey CJ, Green C, Elliott DB. Assessment of referrals to the hospital eye service by Optometrists and GPs in Bradford and Airedale. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2010;31(1). doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-1313.2010.00797.x

- LOCSU. Welcome to LOC-Online. Available from: www.loc-online.co.uk/

- Primary Eyecare. Minor Eye Conditions Service. Available from: primaryeyecare.co.uk/services/minor-eye-conditions-service/

- Primary Eyecare. Community Urgent Eyecare Service. Available from: primaryeyecare.co.uk/services/urgent-eyecare-service/

- Health and social Care. NI PEARS Scheme. Available From: online.hscni.net/our-work/ophthalmic-services/eyes/

- NHS Wales. WGOS Service Information. Available from : www.nhs.wales/sa/eye-care-wales/eye-care-docs/service-manual-wgos-1-2-pdf/

- NHS Inform. NHS community Eye care. Available from: www.nhsinform.scot/care-support-and-rights/nhs-services/eyecare/nhs-community-eyecare/

- Public Health Scotland. Eye care. Available from: publichealthscotland.scot/our-areas-of-work/primary-care/eye-care/general-ophthalmic-service/eye-examinations/

- General Optical Council. Public perceptions of the optical professions 2015. Available from: optical.org/media/4cwcfj0i/public-perceptions-2015.pdf

- General Optical Council. Public Perceptions Report 2022. Available from: optical.org/media/gqfgdbmz/public-perceptions-report-2022.pdf

- RNIB. The Eyecare Support Pathway. Available from: media.rnib.org.uk/documents/APDF-IN230702_Eye_Care_Support_Pathway_Report.pdf

- General optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. Recognise and work within your limits of competence. London. General Optical Council. 2016. P.11.

- Mollan SP, Begai I, Mackie S, O’Sullivan EP, et al. Increase in admissions related to giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia thumatica in the UK, 2002-13, without a decrease in associated sight loss: potential implications for service provision. Rheumatology. 2015; 54(2) : 375-377. doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keu433

- Mulhearn B, Ellis J, Skeoch S, Pauling J, et al. Incidence of giant cell arteritis is associated with COVID-19 prevalence: A population -level retrospective study. Heliyon. 2023; 9(7). doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17899

- Bilton, EJ, Coath, F, Patil, A. et al. The first giant cell arteritis hospital quality standards (GHOST). Eye (2023). doi.org/10.1038/s41433-023-02604-x

- Maamouri R, Ferchichi, Houmane Y, Gharbi Z, et al. Neuro-Ophthalmological Manifestations of Horner’s Syndrome: Current Perspectives. Eye and Brain. 2023; 15: 91-100. doi.org/10.2147/EB.S389630

- Maclsaac JC, Naroo SA, Rumney NJ. Analysis of UK eye casualty presentations. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2022;105(4): 428-434. doi.org/10.1080/08164622.2021.1937949

- Korva-Gurung I, Kubin A, Ohtonen P, Hautala N. Visual outcomes of anti-VEGF treatment on neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a real world population -based cohort study. MDPI. 2023; 16(7). doi.org/10.3390/ph16070927

- Ghosh S, Salvador-Culla B, Kotagiri A, Pushpoth S, et al. Acute chemical injury and limbal stem cell deficiency- a prospective study in the United Kingdom. Cornea. 2019; 38(1): 8-12.Available from: journals.lww.com/corneajrnl/abstract/2019/01000/acute_chemical_eye_injury_and_limbal_stem_cell.2.aspx

- Moledina M, Roberts HW, Mukherjee A, Spokes D, et al Analysis of microbial keratitis incidence isolates and in-vitro antimicrobial suseptability in the East of England a 6-year study. Eye. 2023; 37. doi.org/10.1038/s41433-023-02404-3

- Stapleton F. Contact lens-related corneal infection in Australia. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2020; 103(4):408-417. doi.org/10.1111/cxo.13082

- The Scottish Parliament. Chamber and Committees Official Report, meeting date September 22, 2021. Available from: www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/official-report/search-what-was-said-in-parliament/chamber-and-committees/official-report/what-was-said-in-parliament/meeting-of-parliament-22-09-2021?meeting=13315&iob=120794

- NHS England. NHS to trial tech to cut missed appointments and save up to £20 million. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/2018/10/nhs-to-trial-tech-to-cut-missed-appointments-and-save-up-to-20-million/#:~:text=With%20each%20hospital%20outpatient%20appointment,is%20coming%20to%20the%20NHS