Back in the dim and distant past when rural practices closed at lunchtime, I was an early career optometrist working solo with a receptionist. The practice was in a busy seaside town where everyone knew each other and the population was predominantly the elderly or seagulls.

It was lunchtime on a squally and wet April afternoon and from the staff room, at the back of our single-story building, I heard frantic rattling of our locked door and rapping on the glass. Initially, my reaction was to ignore it and put the kettle on… we didn’t reopen until 2pm. However, the door rattling became more persistent and so I answered it.

There stood a very distressed, soggy lady; I remember the alarm on her face as it was etched with worry and was puce! Alongside the high colour, her eyes were quite bloodshot too. ‘Please help me,’ was all she said and she gripped my arm. I let her in and sat her down and fetched a glass of water. She held her head in her hands and said ‘make the flashing lights stop please’.

Betty was 67 years old and had not had an eye test since her early 40s. She had grown up with thick spectacles as a child and was frightened of her eyes getting worse. She fished her very scratched, old, ‘taped-up’ frames from her pocket and handed them to me. She thought, by not getting her eyes tested and not updating her specs that she was now the recipient of flashing lights. ‘What have I done?’ she asked, very worried.

I sat a while with her to gain her confidence and settle her. I had never met a patient in such distress. ‘I’ve had a terrible headache for six days,’ she said. ‘I thought it was my infected tooth causing it, but I’ve seen the doctor and I am on some antibiotics now and seeing my dentist next week but the headaches are getting worse.’

Betty had not seen a dentist for nearly a decade and she had also failed to mention the severity of her headaches to the doctor, just her painful tooth. As a result, blood tests and blood pressure were not investigated and she was sent away with some paracetamol and amoxicillin.

I ascertained that the headaches were like a ‘band or vice’ around her head and the flashing lights were constant and bilateral and all sorts of colours; ‘Like “splodges” of red in patches around things.’ There were no floaters at all. She said she could still read without her specs but did not read much.

Mostly she was either in the garden, watching the television or looking after her husband. I consented her for an examination and while she drank her water, I focimetered the rather battered single vision lenses.

RE +1.00/-4.00 x 82

LE +3.00/-4.00 x 90

There were no reading glasses, apparently these were for the television as Betty did not drive. She read unaided. I figured that headaches could be due to uncorrected astigmatism, but as Betty rarely wore her spectacles other than to watch Countdown and the cricket, this did not fit the presenting symptoms of ‘excruciating’ headache.

With the glasses on and finally settled in the consulting room, Betty read a poor 6/18 with each eye. ‘They’ve never been any good, I didn’t get them until I was 10 and by then the eye doctor said it was too late.’ Was she bilaterally amblyopic? Fortunately, I decided that fundus examination was the most pressing investigation before I did anything else – by this time it was 1.40pm. My next patient was due at 2pm.

I popped the room lights off and peered into Betty’s nicely mid-dilated pupils; I was not expecting the view to be so easy. Nothing had prepared me for what I saw next. I looked in the fellow eye and it was the same. Both optic nerves were congested, like ‘champagne corks’, dioptrically in focus at least 2D anterior to the fundus.

There were splinter haemorrhages everywhere, exudates, cotton wool spots and circinate exudates radiating like blurry stars around the macula zone. It was 1996, and imaging technology we now enjoy, such as an OCT machine or fundus cameras, were not available.

The most important piece of kit I had was my brain. Other than my ret and ophthalmoscope, the only tools I had were an old Mark II Friedmann field analyser, a pen torch, a somewhat enthusiastic NCT, a burton lamp and a keratometer in tandem with my very good slit lamp.

I held Betty’s hand and asked her if she wanted me to call anyone for her, I was going to call an ambulance. She needed a blood pressure check and the flashing lights she was seeing may well have been a precursor for stroke. The ambulance arrived at 2.05pm and Betty’s blood pressure was 210/130.

They took her to the local district hospital where they worked hard to get her blood pressure down, however, she suffered a stroke that same afternoon while her BP was being stabilised. Betty’s husband had called me to let me know the next morning that they were not sure how well she would recover.

Fast forward two months and Betty was wheeled in to see me by her neighbour. She had limited use of her right arm and her face had dropped a little on the right-hand side. Although able to walk with a frame, her right foot was dragging a little, so she preferred a wheelchair.

She had mild dysphasia but had wanted to come in to thank me and to book an eye test. ‘You saved my life,’ she said. ‘If you hadn’t let me in, I’d have gone home and most probably died.’

Hypertension recap

Hypertension is diagnosed when the systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings are considered consistently high. The normal ranges are banded depending on age and sex.

Systolic blood pressure reading: As blood is pumped out of the heart (top number on a blood pressure reading).

Diastolic blood pressure reading: The resting pressure as the heart rests between beats (lower number on a blood pressure reading). High blood pressure is often thought of as a consistent reading of 140/90mmHg or above. Ideal/target blood pressure 120/70mmHg – 130/80mmHg depending on age.

Pathogenesis of hypertensive retinopathy

Uncontrolled or poorly controlled hypertension can lead to multifactorial complications affecting the major organs and systems in the body. This is known in the medical specialties as target organ damage; cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, renal and ocular manifestations.

Hypertensive eye disease affects all the major structures of the eye; from choroidopathy, to retinopathy and optic neuropathy.

The severity of hypertensive retinopathy has been shown to have a strong correlation to the severity and duration of the hypertension, which itself is linked to the incidence of target organ disease.3 Often the initial signs of hypertensive retinal changes are asymptomatic and the patient is unaware of any issue until they begin to lose vision due to optic nerve or macula involvement. It has also been shown that patients with greater than grade 2 retinal arteriosclerotic changes and hypertension are at a greater risk of retinal vascular occlusive events4 and the ocular comorbidities which ensue.

There are four phases to hypertensive retinopathy:

- Vasoconstrictive phase – arterioles become narrow thus reducing the arterio-venous ratio (A:V normal considered to be 2:3)

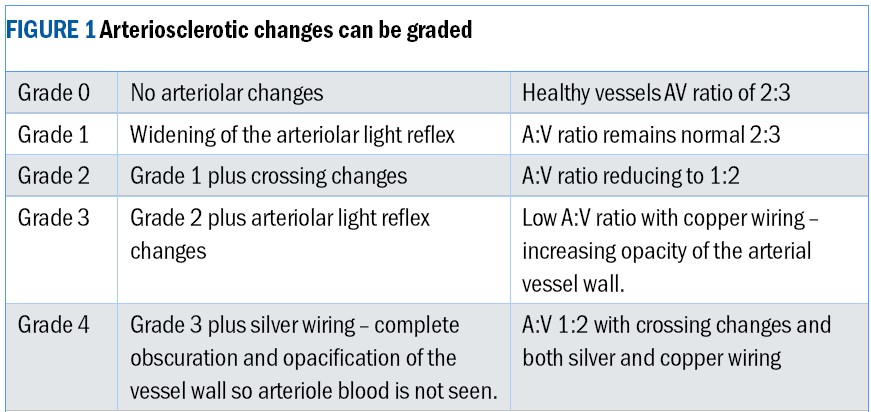

- Sclerotic phase – Sclerosis causes vessel wall changes, thickening of the intima layer and hyperplasia of the media layer. There is hyaline degenerative change of the arteriolar wall. Arterio-venous crossing changes become more accentuated with wider and increased light reflex of the retinal vessels; This is known as copper and later silver wiring. This is a sign of persistently raised blood pressure. The veins become compressed by the arteriole crossing them. Venules have thinner vessel walls and the compression causes nipping or tapering of the vein (Gunn’s sign) and banking either side of the crossing (Bonnet’s sign). There are several stages to this sclerotic phase (figure 1), which can occur in tandem with early exudative signs as ocular morbidity progresses.

- Exudative phase – This occurs when the blood/brain barrier has become compromised by persistent severely raised blood pressure. Plasma and blood products are able to leak in to the damaged vessel walls and into the surrounding tissues. Retinal signs of this exudative phase include flame haemorrhage, focal ischaemia with cotton wool spots, exudative deposits with dot and blot haemorrhages.

- Malignancy – In the malignant phase there is raised intercranial pressure sufficient damage to the retinal circulation and choriocapillaris to cause ischaemia and necrotic changes to the choroid. Papilloedema is seen followed by optic nerve ischaemia. There will be retinal findings of all of the above phases in malignancy often accompanied by choroidopathy.

Choroidopathy – seen in chronic hypertensive/malignant eye disease:

- Choroidal infarcts with RPE Hyperplasia – linear pigmentation along choroidal arterial vessels (Seigrist’s streaks)3

- RPE detachment of the neurosensory retina

- Elschnigs spots – seen after choriocapillaris occlusive events; isolated small circular islands of RPE clumps surrounded by a pale ring of depigmentation9

Malignant hypertension is life-threatening and the retinal findings and symptoms associated indicate a true medical emergency requiring urgent same day hospital admission.

Hypertensive retinopathy is diagnosed in stages based upon vascular and retinal findings, however, there is still no standardised hypertensive grading scale for retinopathy although some models exist.

Risk factors associated with Hypertension

There are many risk factors which can increase the risk of suffering with hypertension. Some, but not all can be mitigated with simple steps and changes to lifestyle choices.

- Increasing age – encourage exercise to increase mobility and maintenance of a healthy lifestyle

- Obesity – encourage maintaining a healthy BMI by introducing lifestyle changes and consuming a balanced healthy diet

- High salt diet – low salt/sodium diet recommended/ low salt alternatives

- Smoking – cessation recommended

- High cholesterol – dietary adaptations and discussing with general practitioner regarding use of statins

- High alcohol intake – maintaining guideline alcohol consumption as a maximum

- Sedentary lifestyle – introducing routine activity recommended

- Genetic predisposition (familial hypertension) – encourage regular monitoring for hypertension and avoidance of lifestyle choices which exacerbate hypertension

- Race – Afro-Caribbeans carry a higher risk of hypertension compared to European races

- Sex – females are more at risk than males

- Diabetes – higher risk of hypertension with type 2 diabetes and type 1 diabetes

- Pre-eclampsia in pregnancy – will be monitored for by antenatal team

- Adrenal or para-adrenal gland tumours (eg phaeochromocytoma) – should be suspected in younger patients with hypertensive fundi and no history of poor lifestyle or hypertensive risk factors. Treatment is usually surgical

Common Symptoms of malignant hypertension

- Persistent vice-like headache

- Confusion or altered conscious state

- Blurred or disturbed vision

- Chest pains

- Palpitations/changes to pulse

- Generally feeling unwell

- Stroke

Ocular Sequelae

Hypertensive retinopathy is not just a harbinger or systemic disease, it can also lead to unwanted ocular complications, which in turn can lead to sight loss:

- Worsening diabetic retinopathy

- Retinal venous occlusion and associated risk to the macula and secondary glaucomas

- Retinal arterial occlusion

- Retinal detachment

- RPE neurosensory detachment

- Choroidal necrosis

- Optic nerve neuropathy

- Maculopathy

- Glaucoma

- Epiretinal membrane

- Cystoid macula oedema

Management and referral

Primary care physicians and optometrists work together to try to ensure risk factors are mitigated with patient education and effective screening of retinal vasculature during routine eye examinations. The eye is the only organ where the circulation can be easily viewed and monitored with ease and hypertensive changes can be easily spotted and monitored.

Significant changes to the retinal circulation should be referred on to the patient’s general physician for monitoring of blood pressure and treatment as necessary. Patients who present with grade 2 or worse with or without haemorrhage or exudative event should be managed by their physician.

The advances and accessibility of retinal photography is an excellent way to educate the patient as well as keep a contemporaneous record of the health of the circulation at each visit.

Treatment of hypertensive crisis

Patients showing signs of hypertensive crisis require emergency admission on the same day and often are looked after in a high-dependency or intensive care setting. They will undergo extensive blood tests;1 urea and electrolytes, lipid profile analysis, full blood count, fasting blood sugars, erythrocyte sedimentation rate as well as electrocardiography.

They will be treated with oral and intravenous antihypertensive therapy until the blood pressure is slowly and carefully stabilised while the extent of target organ involvement/disease is assessed. Life expectancy is reduced after hypertensive crisis as the risk of stroke and cardiovascular and circulatory disease remains high as the damage often cannot be reversed.

The mortality rate for late diagnosis or poorly controlled hypertensive crisis is very high with 50% survival rate of two months and 90% of survivors pass within a year.3 Vascular occlusive events as well as hypertensive signs have both been shown to pose a significant increased risk of cerebrovascular accident.6

Conclusion

Over the years there have been many advances in the treatment of hypertension, however, leaving hypertension undiagnosed or untreated can lead to catastrophic life changing events as outlined in the case study.

There is a close link between systemic complications of hypertension, even when the patient is being medically managed due to the insidious and chronic nature of the disease. The damage is already done and mitigating further decline is of paramount importance.

End note

As for Betty, she continued to be a loyal patient. I saw her every six months and she did buy some really lovely spectacles, which she looked after carefully but preferred to save them for ‘best’. Her vision never recovered beyond 6/18 – reduced due to her optic neuropathy, however, she was happy pottering in the garden and enjoying her quiz shows on the telly.

She never did completely get rid of her flashing lights and I was ever watchful for retinal detachment. Sadly, despite relatively good hypertensive control, the damage was already done. There was persistent exudative retinopathy with flame haemorrhages and hard exudation, which never completely cleared.

Peripapillary collateral retinal circulation eventually developed, which was unstable and would also be prone to focal leakage. She died of a second catastrophic stroke two years after her initial hypertensive crisis.

- Sarah graduated from City University in 1993. Her work has taken her from sub-Saharan Africa to the Hospital Eye Service, Academia and Independent practices in Devon and for the last 25 years in Hampshire. She is involved in the sight loss sector, presenting training and patient facing content for those living with sight loss and their colleagues and families. Sarah is currently on sabbatical, working closely with support services for those with visual impairment.

References

- Bruce, O’Day, McKay and Swann (Optician.net 2007) – Hypertensive Retinopathy

- W, Waymack JR. Central Retinal Artery Occlusion. [Updated 2023 Sep 4]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470354/

- Modi P, Arsiwalla T. Hypertensive Retinopathy. [Updated 2023 Jul 4]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525980/

- Kim HR, Lee NK, Lee CS, Byeon SH, Kim SS, Lee SW, Kim YJ. Retinal Vascular Occlusion Risks in High Blood Pressure and the Benefits of Blood Pressure Control. Am J Ophthalmol. 2023 Jun;250:111-119. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2023.01.023. Epub 2023 Feb 1. PMID: 36736752.

- Woo SC, Lip GY, Lip PL. Associations of retinal artery occlusion and retinal vein occlusion to mortality, stroke, and myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Eye (Lond). 2016 Aug;30(8):1031-8. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.111. Epub 2016 Jun 3. PMID: 27256303; PMCID: PMC4985669.

- Zhou Y, Zhu W, Wang C. Relationship between retinal vascular occlusions and incident cerebrovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jun;95(26):e4075. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004075. PMID: 27368050; PMCID: PMC4937964.

- Abdelwahab W, Frishman W, Landau A. Management of hypertensive urgencies and emergencies. J Clin Pharmacol. 1995 Aug;35(8):747-62. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1995.tb04116.x. PMID: 8522630.

- Hammond, S, Wells, JR, Marcus, DM and Prisant, LM. (2006), Ophthalmoscopic Findings in Malignant Hypertension. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 8: 221-223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-6175.2005.04147.x (image 1)

- Bourke K, Patel MR, Prisant LM, Marcus DM. Hypertensive choroidopathy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2004 Aug;6(8):471-2. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.3749.x. PMID: 15308890; PMCID: PMC8109303.