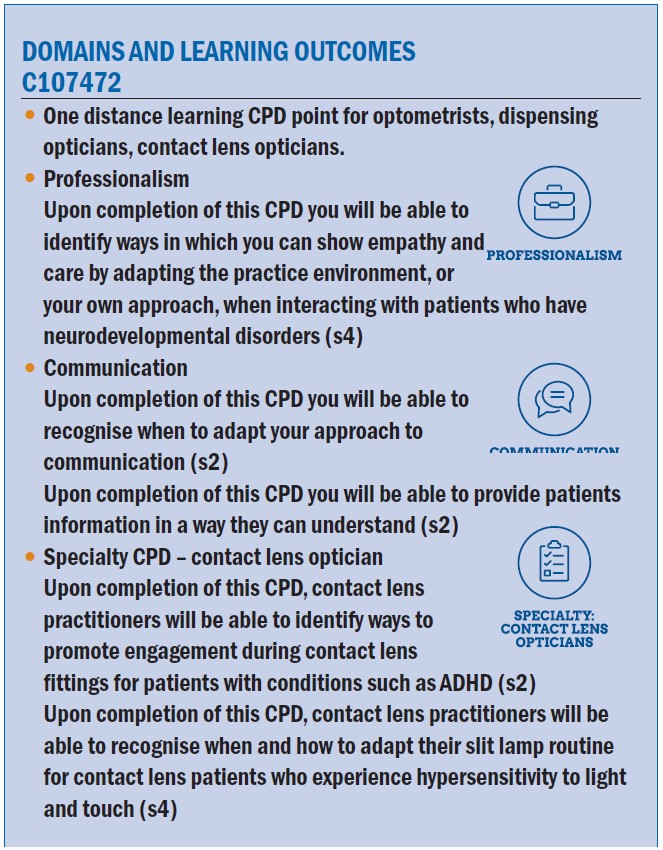

Figure 1: Examples of common neurodevelopmental disorders

The World Health Organization defines neurodevelopment disorders as a group of conditions that lead to functional impairments causing difficulties in social, cognitive and emotional functioning. Common examples of such conditions (figure 1) include autism spectrum condition (ASC/autism), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and disorders that impact intellectual, communication, learning or motor abilities.1

The challenges faced when grouping complex diverse disorders together, is there are often unclear boundaries between conditions and comorbidity is common.2 Studies across the globe have reported a large ranging prevalence of neurodevelopment disorders among children of between 4.7-88.5%.3 There has also been changes to reflect more politically correct nomenclature, all having resulted in various terms and language used.4

Most individuals with a neurodevelopment disorder will have challenges with learning and approximately 1.5 million people in the UK have a learning disability (2.16% of adults and 2.5% of children).5,6 The National Institute of Clinical Excellence defined a learning disability as: a low intelligence quotient (IQ) (under 70), significant impairment of social or adaptive functioning, and onset during childhood.7

Examples are broad ranging and include genetic conditions such as Down’s syndrome and Fragile X syndrome or linked to infections, brain injury, exposure to toxic substances, birth complications or interferences in brain development including cerebral palsy.

Learning difficulties are a subcategory to cover those with a reduction in certain academic skills (literacy and numeracy), which does not necessarily affect the person’s IQ, general intelligence or independence. Examples include dyslexia, dyscalculia, ADHD and ASC.

Contact lenses for individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions

The broad spectrum of neurodevelopmental conditions clearly highlights that a ‘one size fits all’ approach with eye care provision will not generate the best patient outcomes. In clinical practice, we can expect to see children and adults with neurodevelopmental disorders. For these individuals, apart from providing the required basic eye care, should we consider contact lenses as a

visual correction option or even a myopia management intervention?

The answer may not be that clear cut given the multifactorial nature and varying severity of these conditions. Being adaptable and tailoring our decisions relative to the individual’s need will aid determining contact lens suitability. Surprisingly, despite the many psychological, practical and visual benefits of contact lenses,8 while guidance is available from professional bodies on communication aspects and reasonable adjustments to make during the eye examination there has been little published on contact lens fitting for these special populations.

However, one of the initial barriers may in fact be down to us, as eye care professionals (ECPs), not initiating these conversations.9 With the right motivation, fitting is possible following a comprehensive risk-benefits analysis including reviewing potential risk factors, handling aspects, likelihood of good compliance, eye/general health aspects and the patient’s ability to communicate any sub-optimal performance or symptoms/signs of infection. The support network around the individual can also be utilised to overcome any challenges and monitoring progress.

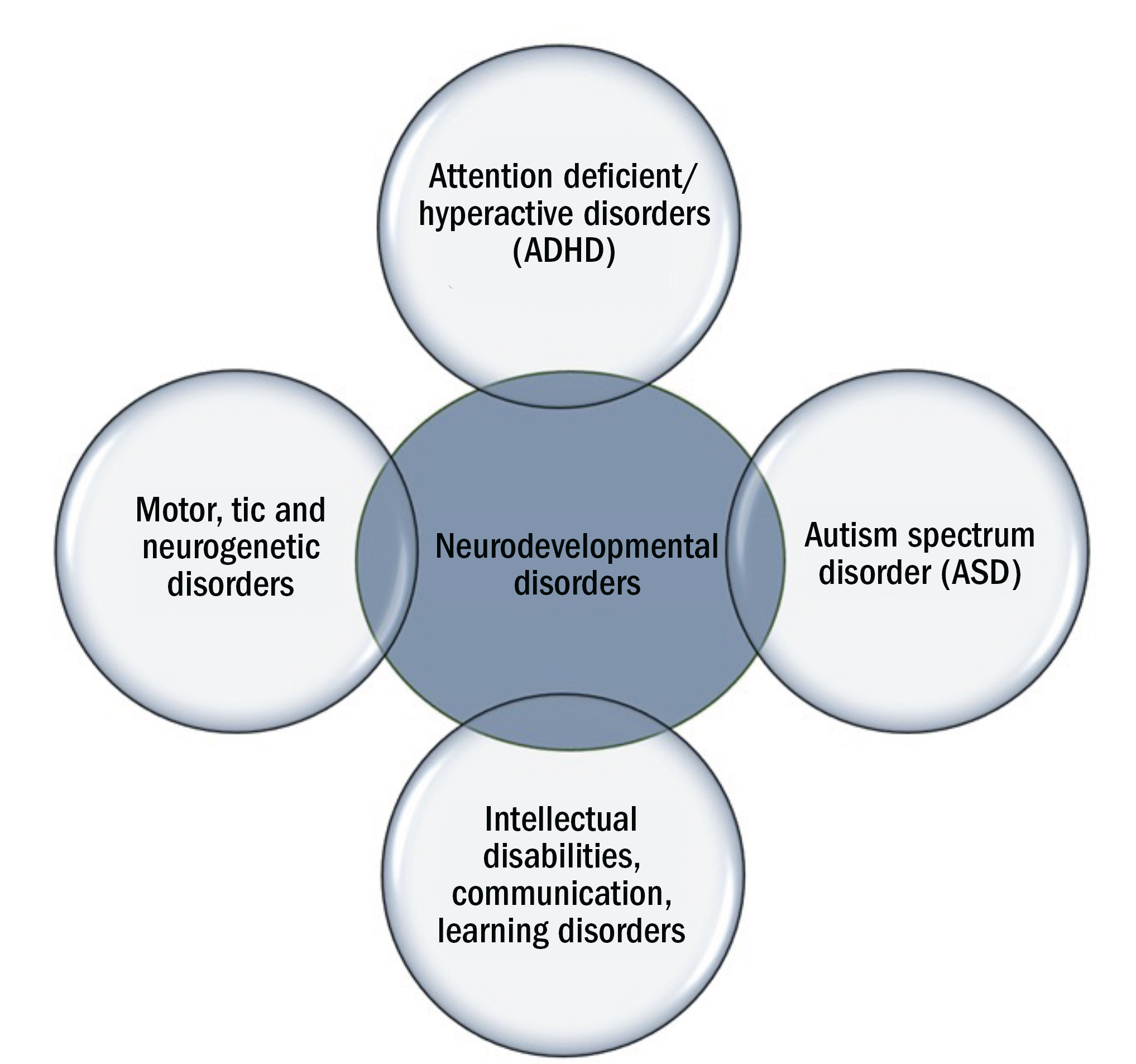

Additional important aspects include our duty to establish capacity, obtaining consent, involving others in decisions regarding the patient’s care (where appropriate), communicating in a manner easily understandable to all parties, appropriate record keeping and ensuring safety. Contact lenses must not be fitted if patient safety is likely to be compromised (figure 2); in addition to ensuring we work within our scope of practice.10 Where a patient’s capacity to give consent is impaired or limited, obtaining the consent of the person with legal authority to act on behalf of the patient should take place.

Figure 2: Reasons where contact lens wear would be contraindicated

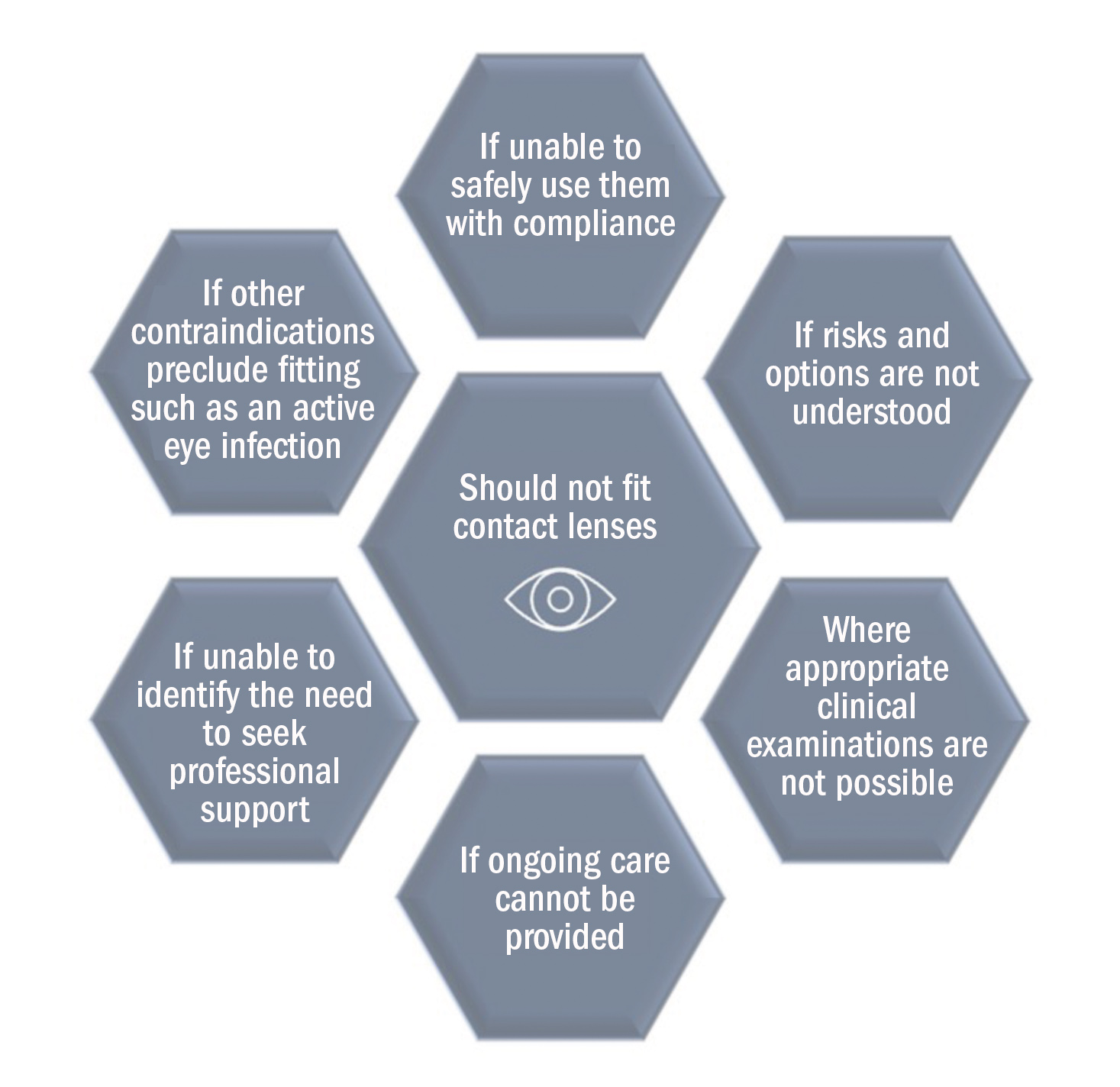

The remainder of this article explores the role contact lenses may play in addressing the eye care requirements of special populations using case examples. Safe contact lens wear is the goal, and suitability should be determined on a case-by-case basis, with the patient fully involved in the decision-making process. Approaches should follow an evidence-based approach (figure 3), which considers best practice guidance available, applying clinical judgement and incorporating any preferences of the patient/carer.11

Figure 3: Evidence-based contact lens fitting approach. It is important to maintain a good balance between currently available guidance, one’s clinical judgement and the needs of the patient

Case 1: Ben – a patient with ADHD

ADHD is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder affecting the individual’s ability to exert age-appropriate self-control, usually through patterns of impulsive hyperactive behaviour and periods of inattentive activity. Emotional regulation challenges may also occur, however, with the right support and treatment individuals can learn to manage these challenges.

The prevalence of ADHD in the UK has been reported to be 3.62% of boys and 0.85% of girls12 and 3-4% of adults.13 There is a higher likelihood of refractive error, binocular vision (eg strabismus, amblyopia, and symptomatic convergence insufficiency), visual field defects and colour vision deficiency in children with ADHD compared to those without.14-17 This highlights the importance of individuals with ADHD undergoing a thorough eye examination to rule out, and where appropriate treat, any underlying vision issues that are likely to impact vision-related quality of life.

Ben is 15 years old and was diagnosed with ADHD three years ago. He wears glasses full time (R&L -2.00D 6/5 N4) although regularly breaks them. His mother reports he is ‘doing well at school, when he stays focused’. On examination there are no clinical/eye health contraindications to contact lens wear identified. He is compliant with taking his medication (5mg methylphenidate twice per day). He seems engaged during the eye test and capable of understanding information and making decisions, although easily becomes distracted. Ben loves sport.

His mother asks if contact lenses would be a good option.

Would you fit Ben with contact lenses?

We know children generally do well with contact lenses and are compliant.18 If Ben is motivated and consents, his impulsive and ‘make it happen’ tendencies can be used as a strength and with the right approach his energy can be focused on this exciting new opportunity to wear contact lenses. He seems to be able to understand information and willing to be involved in decisions.

His vision is good and Ben appears to have good family support. The usual contact lens options (soft and rigid materials) and fitting process are applicable and should be discussed. Regarding soft lenses, a daily disposable may be advantageous over reusable due to the increased ease and convenience. If handling becomes an issue or Ben’s mother would like more control and the ability to monitor progress, then orthokeratology lenses may be the preference.

Risk factors

Ben is taking one of the most commonly prescribed medications for ADHD and although the majority (approximately 70%) of those who take methylphenidate see improvements in ADHD symptoms,19 there are some who appear to be at more risk of ocular side effects when compared to those not taking medication and it is also contraindicated for those with glaucoma.

Methylphenidate is a central nervous system stimulant that increases the levels of neurotransmitters in the brain, which play a part in controlling attention and behaviour. Although there are some adverse ocular responses to these medications such as blue-yellow colour vision problems,20 other aspects such as the increased likelihood of ocular surface pathology, namely dry eyes when taking these medications21 are more significant here.

Interestingly, dry eye is only listed as a rare side effect, whereas visual disorders are more common.22 Nevertheless, it is important to take a detailed patient history and conduct a thorough ocular surface assessment for these individuals prior to a contact lens

fitting. To maximise fitting success the most likely reasonable adjustments are linked to communication aspects and making the contact lens fitting journey as efficient as possible, ensuring Ben is fully aware of the process and some top tips are highlighted in table 1.

Younger children on average may need slightly longer to master contact lens handling skills during the contact lens teach,23 although no such research has been done specific to individuals with ADHD. For Ben, learning this new skill may need careful consideration to find the optimal approach that most suits his personality and learning style. Making the experience a game, engaging and reminding Ben of his motivation for lens wear and linking to the potential benefits are likely to be advantageous. Flexibility will be key; it may be that several visits with shorter durations for the teach will provide better results using a variety or supporting resources. Offering a courtesy follow-up call during the first week would also be a good idea.

Case 2: Tina – a patient with autism

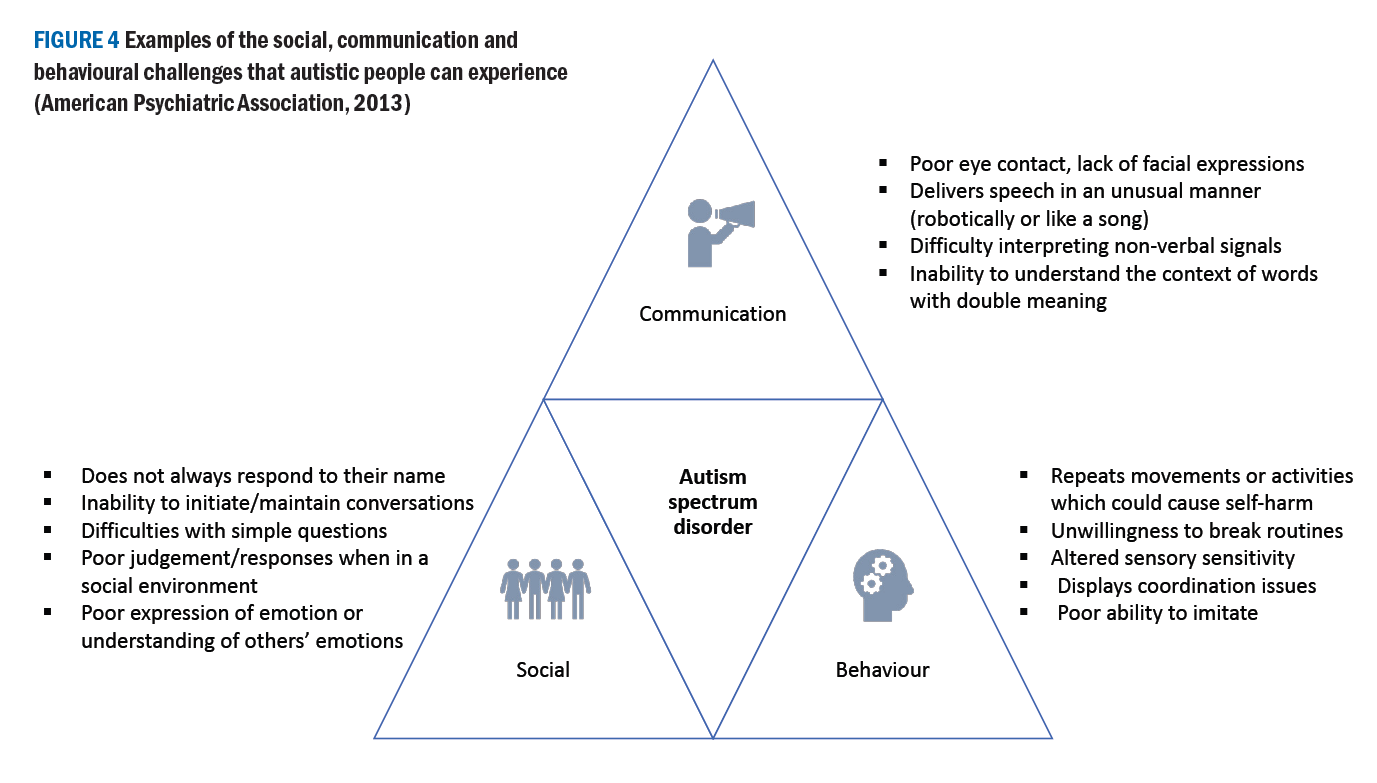

Autism characteristically affects communication, social interaction and behaviour (figure 4). These impairments have stressful impacts on the day-to-day living of autistic people.24,25 Autism is not an intellectual disability itself, but about one-third of autistic people have a co-existing intellectual disability.26

Globally, 0.6%-1% of the population are autistic27,28 and there appears to be a gender imbalance, with up to four times more males diagnosed as autistic than females.28 In the UK, approximately 1.1% of adults29 and 1.57% of children30 are diagnosed as autistic.

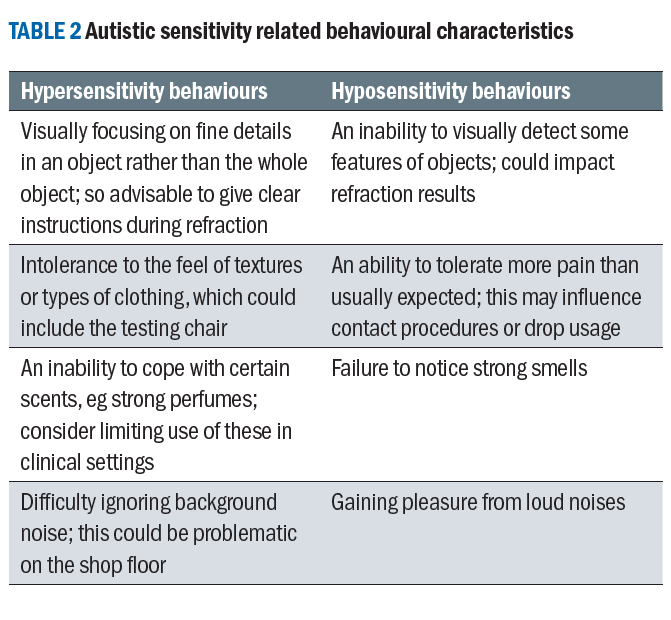

The majority of autistic people have altered sensory reactivity,31 meaning they experience sensory stimuli differently to people without autism. They can be hyper- or hypo-sensitive to sensory stimuli (table 2), which may have an impact during eye examination and contact lens assessments.

Additionally, autistic people can display sensory seeking behaviours such as excessive touching of object edges or fascination with reflections.32 Research has shown the degree of altered sensory reactivity increases with the severity of autism33 but not age.34,35 Importantly, sensory issues are lifelong, affect each sense36 as well as multisensory processing.37 The impact of these can vary from stressful to pleasant, depending on the nature of the resultant experience.38,39

Autism and vision

Although visual acuity is comparable between autistic people and those without,40 autistic individuals are at greater risk of developing optometric anomalies including higher refractive errors and binocular vision anomalies (eg strabismus, amblyopia and accommodation problems).41,42 Therefore, like individuals with ADHD, autistic patients should undergo a thorough eye examination to manage any vision issues; some autistic visual experiences have been found to overlap with typical symptoms of optometric problems.43

Autistic adults can experience a variety of visual symptoms.43

The majority are sensory and due to different aspects of light (bright, fluorescent and spot lighting), strong colours, patterns, motion and visual clutter. These vary from person to person and can occur alone or as part of a larger multisensory experience. Although non-autistic people would probably experience some of these symptoms, it is the challenge in daily activities, such as the ability to complete day-to-day tasks, visit public places (eg hospitals and supermarkets) or use public transport which seems to be greater for autistic people.

Visual sensory issues negatively impact physical, emotional and mental wellbeing. Coping strategies can involve adapted lighting in artificially lit environments, avoiding situations that provoke visual sensory experiences, specific eyewear that prevents distraction (eg spectacles with thinner rims or rimless) and just trying to cope as best possible.

Tina is a 25-year-old vocational course student. At her last eye examination, Rx found R&L -3.00/-0.50x10 6/5 N5. Tina mentioned that she does not like wearing her spectacles because of distraction caused by the frame. She has tried various spectacle frames over the years and currently has a thin, metal frame. The optometrist had discussed the possible advantages of contact lenses with Tina.

You see a note on file that Tina is autistic. She can be sensitive to bright lights and touch. Would you pursue recommending contact lenses?

Contact lens considerations

Tina’s case does not cast any red flags for contact lens fitting. However, noting that she has difficulties with bright lights and proximity, the ECPs would need to consider how the clinical visit can be made more accessible. Parmar et al42 provide a detailed list of evidence-based recommendations to make eye care more accessible for autistic patients. In summary, these include:

- Grasping a basic understanding of autism and the day-to-day challenges that this population may face.

- Introducing alternative options for booking appointments, counteracting the difficulty many autistic people experience with phone calls.

- Offering appointments at quieter times of the day or spreading them across multiple visits.

- Asking patients about special requirements in advance of their appointment.

- Providing the patient with ‘what to expect during your appointment’ information, allowing them to prepare for who they will meet and what processes they will undergo.

- Minimising the number of staff and rooms involved in an appointment to minimise anxiety caused by unfamiliarity.

- Establishing a good rapport with clear, friendly communication and being aware of how the patient is coping with the experience.

- Ensuring all the patient’s presenting concerns are addressed.

At the contact lens fitting appointment, the practitioner should introduce themselves and describe the purpose of the appointment so that Tina knows what the expected outcomes are. Tina may need some time to familiarise herself with the clinic room and to become comfortable around the practitioner. A positive aspect of eye care is the structured nature, with most clinical tests being distinct from each other and presented in a logical sequence.

Therefore, the practitioner should work through the examination routine, ensuring they explain to Tina the purpose of the test, show casing the equipment that will be used (for example the slit lamp), describing how the test will be conducted, ‘I am going to use this microscope to have a closer look at your eyes – this will involve a bright light being shone at your eye’, and confirming that Tina understands what she will be expected to do. Good observational skills are important as, if there are signs that Tina is becoming distressed or tired during the appointment, a break should be offered, clarifying if she would like to continue or take the opportunity to resume on another day.

Tina has reported difficulties with bright lights and touch, both of which are common as part of eye care. Adaptions could include asking Tina to cover her eye with her hand rather than using an occluder, or to hold her own eyelids while instilling drops or applying contact lenses. Practitioners should be wary of strong smells in their clinic room such as perfume as this can be very difficult to cope with for some autistic people.

The brightness of lights should be adjusted or/and making use of filters/diffusers to ensure patient safety and comfort during slit lamp investigations. The practitioner should warn Tina before touching her eyelids and discussing the importance of more invasive tests (fluorescein and lid eversion assessments). If a test is only partially complete record keeping should reflect this.

For Tina, the usual lens selection options and fitting assessment seem applicable and relating to their motivation for contact lenses and personal interests is likely to keep engagement high. A useful tip prior to application of the contact lens in the fitting is to let Tina ‘touch and feel’ the contact lens to address any misconceptions. Reassuring her that the lens will not escape around the back of the eye and how it is likely to feel as gentle as a rain drop on the eye when first applied may help elevate any initial concerns.

The contact lenses teach may typically be conducted by another member of practice staff, however, if Tina is not familiar with this person, she may feel anxious and not communicate as well with them. Therefore, it would be ideal for the same practitioner to continue the teach with Tina, or, if unavoidable, for Tina to know in advance that she will undergo key milestones in the contact lens journey with different members of staff.

Like many patients, Tina may require multiple visits until she is comfortable with contact lens application and removal and a reassuring approach should be maintained. Scheduling a courtesy follow up call in the first week of lens wear, ideally with the same person who was involved with the contact lens teach, would be beneficial to understand progress and provide an opportunity to offer additional support. Depending on their clinical judgement on how Tina is coping with contact lens use, the practitioner may decide to extend Tina’s trial period with extra follow up appointments and to have more frequent aftercare recalls.

Summary

In summary, given the wide range of presentations of those with neurodevelopment disorders, it is conceivable that you may have already fitted an individual with mild symptoms, or who is undiagnosed, with contact lenses. Those unaware or undiagnosed appear to be fairly common for conditions including ADHD and ASC.44 In reality we should embrace the opportunity to adapt our approaches to be more proactive with contact lens fitting to those suitable, through introducing the feel-good factors associated with contact lenses.45

Neil Retallic and Dr Ketan Parmar

- Neil Retallic is an optometrist with experience working in practice, education, industry and head office roles. He currently works

as the head of professional development at Specsavers and as an assessor and examiner for the College of Optometrists. He is the immediate past president of the BCLA and a member of the GOC Education Committee. - Dr Ketan Parmar is an optometrist and lecturer in postgraduate optometry at the University of Manchester. He completed his PhD in 2022 and his research areas of interest includes investigating autism, vision, clinical optometry and accessible eye care.

References

- WHO. Mental Disorders. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders#Neurodevelopmental% 20Disorders

- Morris-Rosendahl DJ, Crocq MA. Neurodevelopmental disorders-the history and future of a diagnostic concept Dialogues Clin Neurosci. Mar 2020;22(1):65-72. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.1/macrocq

- Francés L, Quintero J, Fernández A, et al. Current state of knowledge on the prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood according to the DSM-5: a systematic review in accordance with the PRISMA criteria. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. Mar 31 2022;16(1):27. doi:10.1186/s13034-022-00462-1

- WHO. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health ICF. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/classification/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf

- PHE. Data from: Learning Disabilities Observatory: People with learning disabilities in England 2015: Main report. 2015.

- ONS. Data from: Estimates of the population for the UK, England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. 2020.

- NICE. NICE learning disabilities. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/learning-disabilities/

- Tanna-Shah S, Retallic N. Health and well-being in eye care practice: Riding the emotional rollercoaster of the contact lens journey. Optician Select. 2021;2021(10):8746-1.

- Retallic N. It’s Good to Talk about Contact Lenses. 2023. https://mivision.com.au/2023/08/its-good-to-talk-about-contact-lenses/

- GOC. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. General Opticial Council; 2016.

- Wolffsohn JS, Dumbleton K, Huntjens B, et al. CLEAR - Evidence-based contact lens practice. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Apr 2021;44(2):368-397. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2021.02.008

- Hire AJ, Ashcroft DM, Springate DA, Steinke DT. ADHD in the United Kingdom: Regional and Socioeconomic Variations in Incidence Rates Amongst Children and Adolescents (2004-2013). Journal of Attention Disorders. 2018;22(2):134-142. doi:10.1177/1087054715613441

- NICE. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder:How common is it? National Insitute of Clinical Excellence. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder/background-information/prevalence/#:~:text=In%20the%20UK%2C%20the%20prevalence%20of%20ADHD%20in,4%25%2C%20with%20a%20male-to-female%20ratio%20of%20approximately%203%3A1.

- Barnhardt C, Cotter SA, Mitchell GL, Scheiman M, Kulp MT. Symptoms in children with convergence insufficiency: before and after treatment. Optom Vis Sci. Oct 2012;89(10):1512-20. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e318269c8f9

- Ho JD, Sheu JJ, Kao YW, Shia BC, Lin HC. Associations between Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Ocular Abnormalities in Children: A Population-based Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. Jun 2020;27(3):194-199. doi:10.1080/09286586.2019.1704795

- Reimelt C, Wolff N, Hölling H, Mogwitz S, Ehrlich S, Roessner V. The Underestimated Role of Refractive Error (Hyperopia, Myopia, and Astigmatism) and Strabismus in Children With ADHD. J Atten Disord. Jan 2021;25(2):235-244. doi:10.1177/1087054718808599

- Choudhury RA, Adducci AJ, 2nd, Sarwar H, Hale EW. Researching Eyesight Trends IN ADHD (RETINA). J Atten Disord. Oct 21 2023:10870547231203169. doi:10.1177/10870547231203169

- Walline JJ, Lorenz KO, Nichols JJ. Long-term contact lens wear of children and teens. Eye Contact Lens. Jul 2013;39(4):283-9. doi:10.1097/ICL.0b013e318296792c

- Greenhill LL, Pliszka S, Dulcan MK, et al. Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. Feb 2002;41(2 Suppl):26s-49s. doi:10.1097/00004583-200202001-00003

- Bingöl-Kızıltunç P, Yürümez E, Atilla H. Does methylphenidate treatment affect functional and structural ocular parameters in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder? - A prospective, one year follow-up study. Indian J Ophthalmol. May 2022;70(5):1664-1668. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_2966_21

- Aydemir E, Aydemir GA, Kalınlı M. Evaluation of ocular surface in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with respect to methylphenidate treatment. Arq Bras Oftalmol. Sep 23 2022;doi:10.5935/0004-2749.2021-0290

- BNF. British National Formulary: Methylphenidate hydrochloride. NICE. https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/methylphenidate-children/

- Walline JJ, Jones LA, Rah MJ, et al. Contact Lenses in Pediatrics (CLIP) Study: chair time and ocular health. Optom Vis Sci. Sep 2007;84(9):896-902. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181559c3c

- Oakley B, Loth E, Murphy DG. Autism and mood disorders. International Review of Psychiatry. 2021/04/03 2021;33(3):280-299. doi:10.1080/09540261.2021.1872506

- Uljarević M, Katsos N, Hudry K, Gibson JL. Practitioner Review: Multilingualism and neurodevelopmental disorders - an overview of recent research and discussion of clinical implications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. Nov 2016;57(11):1205-1217. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12596

- Lemmi V, Knapp M, Rahan I. The Autism Dividend. 2017. https://nationalautistictaskforce.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/autism-dividend-report.pdf

- Elsabbagh M, Divan G, Koh YJ, et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism research. 2012;5(3):160-179.

- Zeidan J, Fombonne E, Scorah J, et al. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. May 2022;15(5):778-790. doi:10.1002/aur.2696

- Brugha TS, McManus S, Smith J, et al. Validating two survey methods for identifying cases of autism spectrum disorder among adults in the community. Psychol Med. Mar 2012;42(3):647-56. doi:10.1017/s0033291711001292

- Taylor B, Jick H, Maclaughlin D. Prevalence and incidence rates of autism in the UK: time trend from 2004-2010 in children aged 8 years. BMJ Open. Oct 16 2013;3(10):e003219. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003219

- Green D, Chandler S, Charman T, Simonoff E, Baird G. Brief report: DSM-5 sensory behaviours in children with and without an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(11):3597-3606.

- Simmons D, Robertson A, McKay L, Toal E, McAleer P, Pollick F. Vision in autism spectrum disorders. Vision research. 2009;49(22):2705-2739.

- Robertson AE, Simmons DR. The Relationship between Sensory Sensitivity and Autistic Traits in the General Population. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013/04/01 2013;43(4):775-784. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1608-7

- Kern J, Trivedi M, Garver C, et al. The pattern of sensory processing abnormalities in autism. Autism. 2006;10(5):480-494.

- Liss M, Saulnier C, Fein D, Kinsbourne M. Sensory and attention abnormalities in autistic spectrum disorders. Autism. 2006;10(2):155-172.

- Baum SH, Stevenson RA, Wallace MT. Behavioral, perceptual, and neural alterations in sensory and multisensory function in autism spectrum disorder. Progress in neurobiology. 2015;134:140-160.

- Beker S, Foxe JJ, Molholm S. Ripe for solution: Delayed development of multisensory processing in autism and its remediation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018/01/01/ 2018;84:182-192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.11.008

- Robertson AE, Simmons DR. The Sensory Experiences of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Qualitative Analysis. Perception. 2015/05/01 2015;44(5):569-586. doi:10.1068/p7833

- Smith RS, Sharp J. Fascination and isolation: A grounded theory exploration of unusual sensory experiences in adults with Asperger syndrome. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2013;43(4):891-910.

- Anketell P, Saunders K, Gallagher S, Bailey C, Little J. Brief report: Vision in children with autism spectrum disorder: What should clinicians expect? Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2015;45(9):3041-3047.

- Gowen E, Porter C, Baimbridge P, Hanratty K, Pelham J, Dickinson C. Optometric and orthoptic findings in autism: a review and guidelines for working effectively with autistic adult patients during an optometric examination. Optometry in Practice. 2017;18(3):145-154.

- Parmar KR. An investigation of optometric and orthoptic conditions in autistic adults. The University of Manchester; 2022.

- Parmar KR, Porter CS, Dickinson CM, Pelham J, Baimbridge P, Gowen E. Visual sensory experiences from the viewpoint of autistic adults. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12

- French B, Daley D, Groom M, Cassidy S. Risks Associated With Undiagnosed ADHD and/or Autism: A Mixed-Method Systematic Review. J Atten Disord. Oct 2023;27(12):1393-1410. doi:10.1177/10870547231176862

- Retallic N. The person behind the contact lens. Optician Select. 2021;2021(9):8715-1.