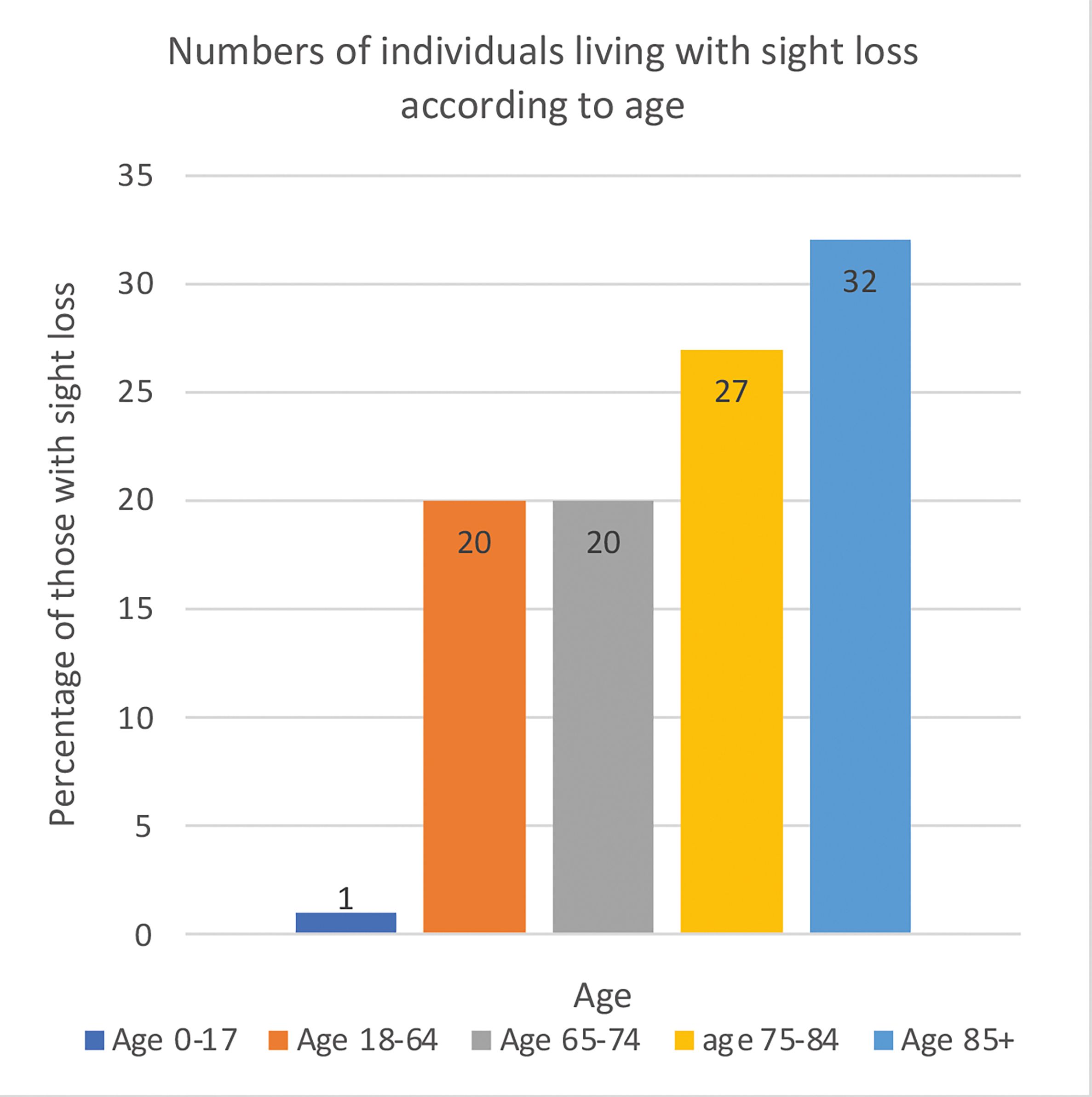

The impact of the loss of one’s sight cannot be underestimated,1 with it one may lose not only one’s sight but one’s independence, job, livelihood, identity, self-esteem, and window on the world. While visual impairment does not discriminate between ages the majority of people with visual loss are over 50 years of age.2

Vision loss is a cause of falls, and elderly patients are more prone to falls and fractures.3 Very young children with vision impairment may experience delayed development in social, cognitive, language and motor skills, resulting in poor educational outcomes and transitioning into an independent adulthood.2,4 Regardless of age many visually impaired patients experience social isolation, anxiety and depression.2

The figures

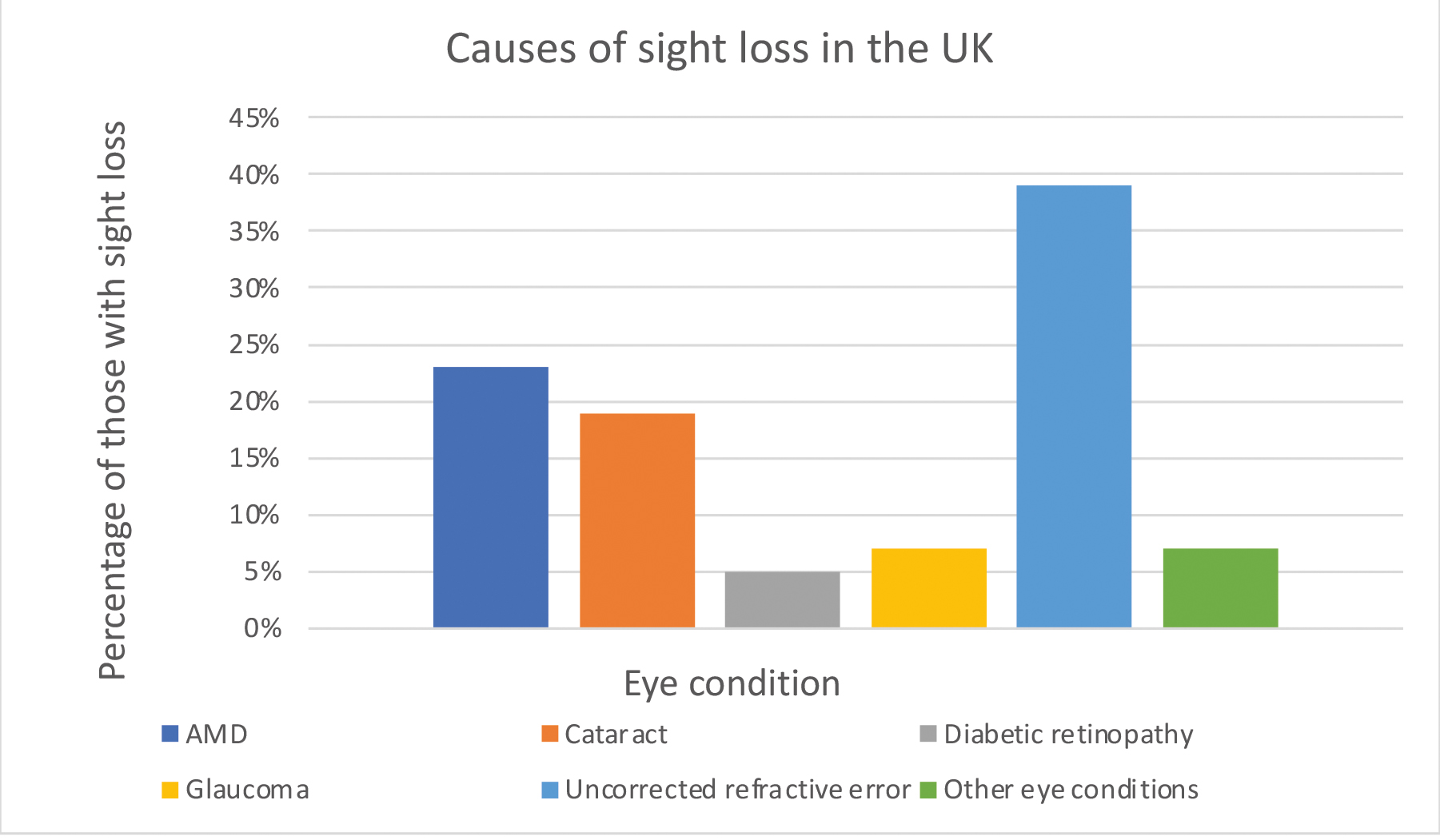

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) at least 2.2 billion people worldwide are impaired by distance or near vision, at least one billion of which cases are either preventable or currently unaddressed.2 It cites that globally the leading causes of visual impairment and blindness are refractive errors, cataracts, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration.

According to the Office for National Statistics, older people are more likely to be disabled.5 UK figures for 2016-17 showed the 65 and over age group accounted for 90% of new cases of permanent sight loss. Over the next 20 years this number is set to increase by almost 50%.6

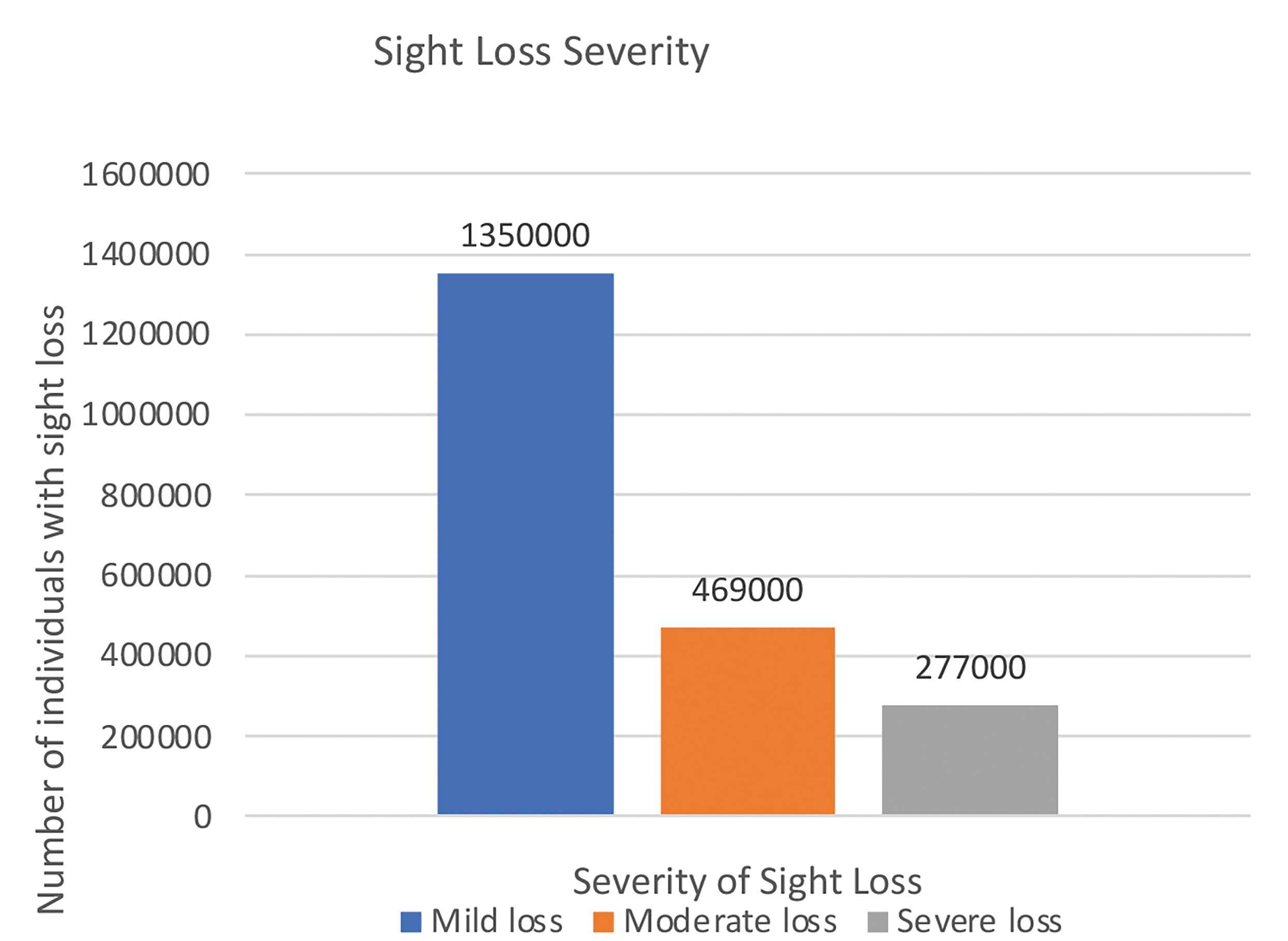

Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) statistics state the total estimated number of people in the UK living with sight loss significant enough to affect their daily lives is greater than two million, this figure is predicted to double by 2050.7 Their figures show that the percentage of females with vision loss is 61% compared to males (39%).

Figure 1: Numbers of individuals living with sight loss in the UK according to age7

So what is the difference between an impairment, a disability and handicap?

Within a health context, ‘an impairment is any loss or abnormality of psychological, physiological, or anatomical structure or function’.8 It is effectively a loss of function as a result of a disease or disorder. In low vision it refers to the physical loss of vision for example, visual acuity, visual field, contrast sensitivity, colour vision, night vision etc and also the resulting psychological effects for the patient. Visual impairment does not necessarily result in disability.

Disability is classified by the WHO as ‘any restriction or lack (resulting from an impairment) of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being’.8 Disability happens when the impairment prevents you from doing the tasks that you would like to do, for example reading, driving, playing sports, using a computer.

It affects the way that a person lives and interacts with society. With appropriate intervention it is worth remembering that many disabilities can be overcome.4 Handicap occurs when an impairment or disability prevents a person from performing tasks that they want to do, and how they interact with society.8 Many healthcare workers no longer use this term.

Figure 2: Causes of sight loss in the UK by pathology7

Figure 3: Severity of sight loss (RNIB figures)7

What is Low Vision?

According to research, many people fail to identify that they have low vision, this may be due to a lack of awareness and education about the symptoms.2,4 Subtle symptoms may be missed1 or misunderstood as normal ageing, or it may be due to denial of the condition.4,9

Low vision is defined in many ways by the different stakeholders with an interest in it. There is no legal definition of low vision. The UK Low Vision Services Consensus Group defines a person with low vision as: ‘…one who has an impairment of visual function for whom full remediation is not possible by conventional spectacles, contact lenses or medical intervention and which causes restriction in that person’s everyday life ’.6

The WHO definition is similar but more detailed and includes a ‘visual acuity of less than 6/18 to light perception, or a visual field of less than 10 degrees from the point of fixation, but who uses, or is potentially able to use, vision for planning and/or execution of a task’.10 It is worth noting that a patient may have relatively good central vision but if they also have a gross peripheral field loss, they may be very disabled and find independent mobility difficult.11

The term blind is very emotive. It has a legal definition which is set out in Section 64 of the National Assistance Act 1948.12 It states that a blind person is someone ‘so blind as to be unable to perform any work for which eyesight is essential’. This definition was only concerned with vision and did not address any of the psychological issues associated with low vision.

There was no legal definition of partial sight in the 1948 Act, only the following guidelines from the 2014 memorandum: a person was considered partially sighted if ‘they are substantially and permanently handicapped by defective vision. This may be congenital or acquired.’13

Certification and Registration

Registration is a two-part process, the first of which is certification. An individual may be certificated but not Registered.13 Pre-2003 a person was certified as blind or partially sighted.12 The form used for the purposes of certification in England and Wales pre 2003 was the BD8,4 in Scotland the BP1, and in Northern Ireland the A655.14

In 2003 changes to certification, the forms used, and the processes involved were introduced. The language used on the forms was changed to more accurately reflect the spectrum of visual impairment13 and address the concerns of patients with some residual vision who had been registered as blind.

With the changes to certification, new documents were introduced which replaced the older documentation (the BD8, BP1, and A655). They gave improved access to support for the visually impaired. Assessment became independent of registration, and registration was no longer required before assessment and provision of services could be accessed by those with a visual impairment.14-16

The new forms helped with the identification, referral, and registration of visually impaired patients. The terminology on the documentation changed, and the term severely sight impaired (SSI) replaced ‘blind’ and sight impaired (SI) replaced the term partially sighted.14

The new documents were the Low Vision Leaflet (LVL),17 the Hospital Eye Service (HES) Referral of Vision Impaired Person for Social needs Assessment (RVI), and the Certificate of Vision Impairment (CVI).18 Each part of the UK currently has its own version of the CVI; in Wales it is the CVIW,19 in Northern Ireland the CVI – NI, in Scotland the CVI – (Scotland).3 The CVI form was updated in 2018.14,15

Copies of the RVI and CVI are available to view online at gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-published-on-registering-a-vision-impairment-as-a-disability.

The LVL is effectively a self-referral leaflet that optometrists and practices may give to a patient presenting with significant visual issues.7,20 The patient is required to complete the form (with help if needed/required), and send it to Social Services to access a needs assessment in their home, which should be provided in a timely manner.16

It may be used where the patient may not have previously had any support – its purpose is to provide the individual with the necessities to support independent living.16 Social care and rehabilitation template letters are also available on the RNIB website.21 The RVI document is intended for use within the HES if registration is declined or not applicable , or the patient did not self-refer using a LVL and is yet to access a needs assessment.22

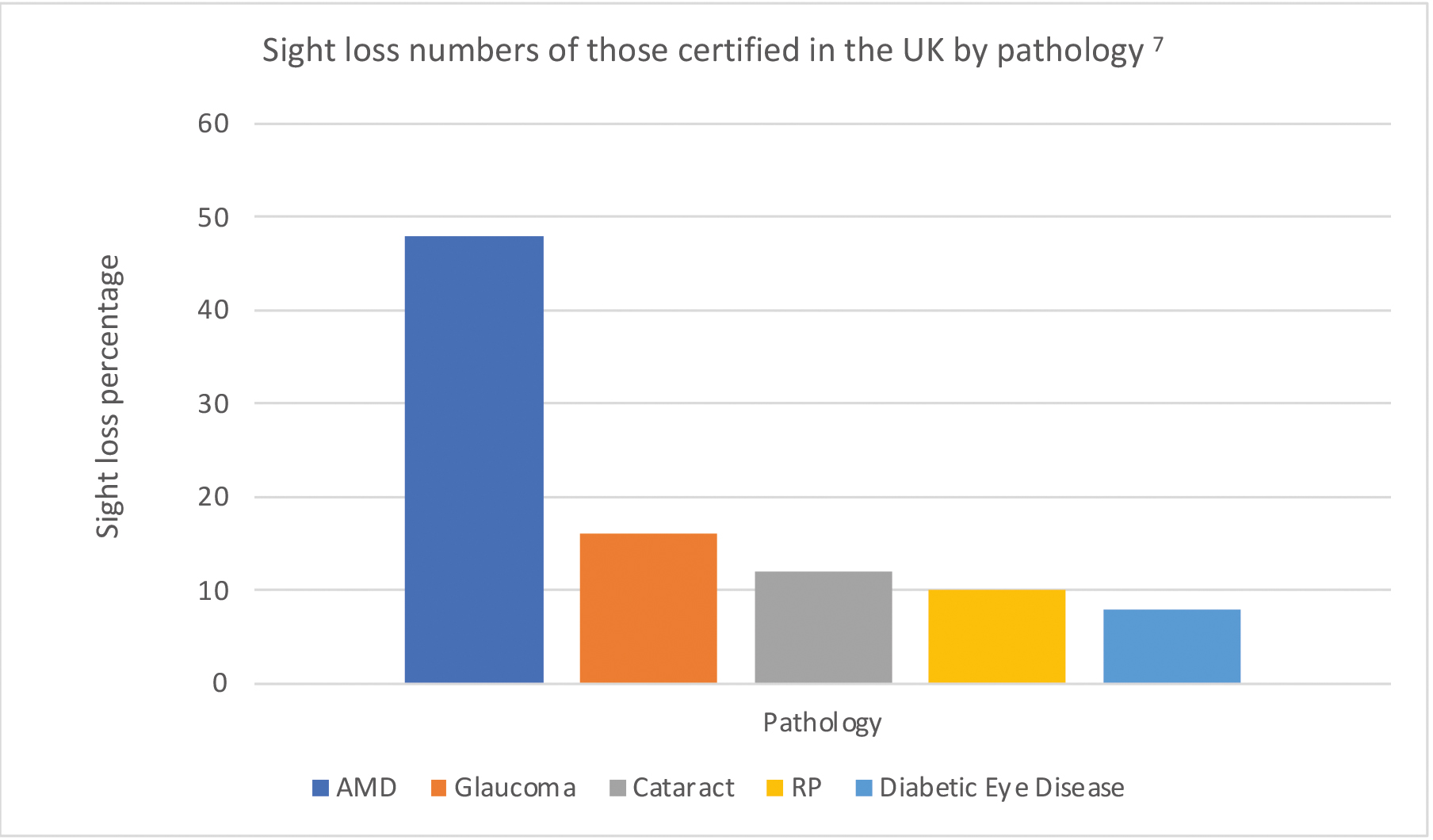

Figure 4: Sight loss numbers of those certified in the UK by pathology

The CVI establishes the patient’s rights to any benefits which depend on registration

The diagnostic section of the CVI and certification must be completed by a consultant ophthalmologist who decides on the category for certification.13 Sections are included for eye clinic staff to express a view on the urgency of the need for social care assessment. To complete certification the CVI form must be signed by the patient giving their informed consent to their information being shared.13

In signing the form the patient acknowledges that driving is no longer possible.14,23 For those patients who are not within the HES a general practitioner (GP), optometrist or low vision practitioner could ask the consultant ophthalmologist to consider certification. The CVI also records data for Moorfields Eye Hospital to use for research at the Royal College for Ophthalmologists into the causes and effects of visual impairment.13

Following certification copies of the CVI form are sent to the patient or parent/guardian if the patient is a child. A copy should be sent to the local council, and the patient’s GP, minus the page on ethnicity, if the patient or parent/guardian consents, these to be expedited within five working days of completion,24 and, a copy is also sent to the Royal College of Ophthalmologists.

More than 24,000 CVIs are issued annually in England and Wales, with about 340,000 registered in the UK, divided relatively equally between the SSI and SI categories25 but these figures are only an indicator of those affected by low vision, as many people choose not to be certificated and registered for reasons which are often complex.

Some see registration as the end of the road and perceive it to be of no benefit whatsoever. Others consider registration and its benefits as a sign of failure and sponging off the State, or as a loss of face and self-esteem. Society generally attaches a stigma to disability and the label of ‘partially sighted, or blind’ for many, carries that stigma.26

There is sometimes a reluctance by the patient to follow up the initial diagnosis of the visual problem, choosing instead not to accept it, thereby decreasing the possibility of referral.9 If a patient is told ‘this is the best I can do for you’ or ‘I can’t do any more for you’ following a sight test, it is unsurprising that some do not follow up on further contact made, feeling that it would be worthless. Many sink into depression26 and may fall off the practice/optometrist’s list.

What criteria are used to classify patients as Severely Sight Impaired/Sight Impaired?

Various factors can be used to assess visual function, but Snellen visual acuity and visual fields are the ones used for the purpose of certification.13 There are two categories for the determination of low vision certification as severely sight impaired and sight impaired, with three groups in each of the two categories. Acuities are determined with the patient wearing their best visual correction.13

Corrected visual acuities (VAs) for severely sight impaired3,13

Group 1: Below 3/60 Snellen, or below 1/18 Snellen if testing at the closer distance, with a full field.

Group 2: 3/60 but below 6/60 with a significantly contracted field. But does not include myopia or nystagmus.

Group 3: 6/60 Snellen or better with a gross visual field contraction, particularly in the lower field. But does not include homonymous hemianopia or bi-temporal hemianopia.

Corrected VAs for sight impaired3,13

Group 1: 3/60 to 6/60 with a full field.

Group 2: Up to 6/24 with a moderate field contraction, media opacities, or aphakia.

Group 3: 6/18 or better with a gross field defect, eg hemianopia, retinitis pigmentosa or glaucoma.

While the decision on which category a patient is to be included in is based on acuity, other factors are also taken into consideration for the purposes of certification, eg the duration of the condition causing the visual impairment; the age of onset – elderly patients may be more at risk and have difficulty adapting; home status – whether the person lives alone or has support at home and other impairments, such as hearing loss.

The fee for completing the registration document is paid for by the relevant health authority. Certification is voluntary and can only be completed by the consultant ophthalmologist. Individuals may choose whether to be registered following certification.13 The above criteria do not refer to infants and young children.

It is considered more appropriate for children under four years of age to be certificated and registered as sight impaired unless obviously blind. Over the age of four the classification for children is the same as for adults depending on the vision/VAs with their best correction.27,28 Schedule 2 of the Children Act 1989 requires local authorities to keep registers of disabled children, including children with sight impairments.29

Registration enables local authorities to plan and budget for health and care support, however access to care and support is independent of registration.13 While Section 29 of the National Assistance Act 194812 requires local authorities to keep registers of disabled persons resident in their area, under Section 77 of the Care Act 2014 local authority Social Services are required to specifically establish and maintain a register of adults resident in their areas who are severely sight-impaired and sight-impaired.30

It places an obligation on local authorities to contact the person issued with the CVI, whether or not they decide to register, within two weeks of its receipt. They are responsible for passing information on to other agencies as appropriate. Notification of registration must be sent to the Department of Work and Pensions for persons of working age seeking employment, and for people on income support.

The patient is entitled to a home visit as part of an Individual Assessment and Rehabilitation Plan and must be made aware of all of the benefits and services available to them from the local authority and other agencies.13

Various Acts of Parliament legislate for additional and specific needs designed to prevent a disability from becoming a handicap.28

What are the benefits of Registration?

While many perceive registration as being of no benefit, the benefits of registration can be tangible and put into various categories:24

- Psychological

- Informative

- Social

- Practical/optical/mobility

- Financial and economic

- Employment

Psychological: Registration may enable the patient to begin the stage of grieving where they come to accept their loss as permanent and to think of it as such.31 When this occurs a more positive outlook may follow what had been a traumatic period, during the stages of the grieving process.

Informative: Until an initial assessment is carried out those with low vision often know, or understand, little about their eye condition and how to access information about it.32 At an assessment or along the pathway to registration opportunities should arise for individuals to get answers or at least be signposted to where to access the answers.

The elderly are often reluctant to ask questions, and time constraints in a clinic may prevent consultants or other hospital staff from having detailed discussions.4 Assessment provides an opportunity in a non-threatening environment to talk and express fears, anger, and frustration to an impartial third party. Even if living within a family, losing one’s sight can result in feelings of isolation.32

Social: The RNIB and other agencies and stakeholders involved in low vision provision are excellent sources of help and support in practical ways, and also in enabling the visually impaired to meet and interact with others who are affected by the same or similar eye conditions and who live independent lives and function fully in a normal work environment.7

Practical/optical/mobility: Many practical and occupational aids can be obtained via hospital eye services, social services and outside agencies for the visually impaired. Practical help around the home, eg large face or talking clocks, large number telephones, special keyboard covers for computers, task lighting, Braille/adapted dials and knobs for cookers, talking scales, typoscopes etc, may be given. Simple optical appliances such as magnifiers, monoculars, simple telescopic units for watching television, tinted spectacles, and more, can also be supplied.21

Many items supplied are on free permanent loan to low vision patients, although provision varies depending on the UK location. A mobility officer may also be provided to help with mobility in and out of the home. In the home help may be in the form of information regarding the layout of the home, or the importance of contrast in and around the home, such as putting contrast edging on the stairs.

Financial and economic: Some of the provision for financial help is only available for those individuals registered as SSI or those already eligible for Income Support etc.20 Benefits such as the Freedom Pass provided by the local authority and the Disabled Persons Badge for cars (Blue Badge Scheme) is of both financial and social benefit as it enables the visually impaired to be more independently mobile.

Automatic benefits and concessions only for those registered SSI are the Blue Badge Scheme, a reduction in the cost of the TV Licence on production of the Certificate of Severe Sight Impairment, and the blind persons tax allowance.16,20

Other benefits/concessions available to both SSI and SI individuals include the Disabled Persons Rail Card, free postage for articles labelled ‘Articles for the Blind’, free GOS sight tests (both SSI and SI individuals), discretionary allowances for work – travel to work and a reader if needed at their place of work, increased income tax allowances, and free passes for carers at events.19 Some benefits and concessions are means tested and not all are free.20,21

Employment: Job Centres may be requested to include the name of the SSI or SI individual on their Disabled Persons Register. Employers have a duty to make reasonable adjustments for disabled job applicants, and employees.33 The Access to Work Scheme can help with travel costs and the costs of practical support at work.34

What factors may help to identify people with a visual impairment or low vision?

For those with undiagnosed pathologies an increase in falls in the elderly may suggest the possibility of a visual impairment/loss if there are no other causative factors.35 However, falls are frequently dismissed in elderly people as being all part of the ageing process.36 Research shows that cataract, glaucoma and retinal degenerations, the main causes of visual impairment, have been found to be independent factors associated with the risk of fall in visually impaired people.37

For some the first sign of vision impairment or loss may occur when driving – not being able to identify a road sign, number plate, or a bus number, or failing to recognise a familiar face, or when executing fine tasks like sewing, or locating a keyhole.38,39 When playing a familiar sport such as a ball sport, an individual may find they find they have trouble seeing the ball, or they may incur injuries as a result of poor vision and increased reaction times. It could result in previously active patients becoming less active, with a reduction in activity leading to a decline in general health.40

Figure 5: Visual impairment does not discriminate between ages and can affect all family members

Quality of Life and Low Vision

The WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) defines terminology used to describe the consequences of disease. It defines quality of life (QOL) as ‘an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns’.41

When compared to other chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, hearing impairments, and coronary syndrome, low vision has a greater significant impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL).42 Although physical and mental health were found to play an important role, the type of visual impairment was found to be a strong indicator of QOL in those affected by low vision,43 with the specific pathology, its onset and duration determining factors leading to specific patterns of visual field loss.1

Research shows that non-visual factors have a stronger influence on QOL in people with low vision than visual factors.43 It suggests that it is important to consider the psychological adjustment to low vision when considering QOL for visually impaired patients. According to Tseng et al44 there is a significant link between sensory impairment and QOL, the severity of the hearing or visual impairment lowering QOL, and QOL with a dual sensory impairment worse than for hearing or visual impairment alone.

Study results of children between the ages of three and 17 years45 and older adults11 with visual impairment found that they experienced a significant reduction in their quality of life, particularly in the areas of mobility, social interaction, and emotional well-being.

Vision loss is a loss akin to any other profound loss such as death, divorce, terminal illness, loss of a limb, job loss etc.46-48 The loss model is a useful tool which provides a theoretical framework for understanding the stages of grief that may be experienced by profound loss. Models suggest that the loss of vision leads to a series of losses, including the loss of independence, social

isolation, and reduced participation in daily activities.44 Understanding its stages can help to improve the QOL of visually impaired individuals. Many theories of grief have been proposed. This author has personally found the ‘stages model’ of grief proposed by Kubler-Ross48 useful in understanding patient response and the utility of advice in certain circumstances.

The model proposes five stages, which include shock, denial, anger/grief, depression and finally (and hopefully) realistic acceptance.49 These stages can manifest in any order and some stages may be revisited frequently during the cycle of grief, which for some may be relatively short, or may take years to achieve, if at all.

It is also important to remember that visual impairment not only affects the individual concerned but also their family members – both adults and children.50 Previous family roles may be reversed, sometimes suddenly. The main income provider may no longer be able to, or feel able to, continue in their previous job/role resulting in a loss of income.

A partner or spouse may unexpectedly have to find a new job to supplement or increase the family income. Household chores may fall on someone not used to doing them, eg bill paying, household administration and organisation, cooking, laundry, DIY, driving, car maintenance, garden maintenance, sorting household rubbish and putting out the bins, to name but a few, which can lead to resentment.

Hobbies once enjoyed may be reduced or abandoned by both the person with vision loss and their partner and children.11 The school run may no longer be an option and prove an organisational challenge. Such burdens have the potential to strain a previously happy relationship,11 which in some cases may prove insurmountable. Low vision rehabilitation services, such as vision rehabilitation therapy and mobility training can improve the quality of life of individuals with visual impairment.7

The impact of sight loss is life changing, both optometrists and dispensing opticians in routine clinical practice will see patients that are experiencing difficulties with their vision. Identifying low vision patients is essential, as this will ensure they can be signposted to, and receive, the additional support that is available whether through certification and registration or local low vision services, thereby improving their quality of life outcomes.

- Gillian Smith BSc (Hons), FBDO Hons (SLD), Hons (LVA), Cert Ed. Smith is an ABDO principal theory examiner, and senior practical examiner at PQE, FQE and Low Vision (Hons) levels, teaching and examining both nationally and internationally. She was senior lecturer at ABDO College (2001-2020), and an associate lecturer at Canterbury Christchurch University (2008-2020). Smith has worked in clinical dispensing and low vision practice, and presented and run revision and CET courses to the profession. She was awarded the ABDO Medal of Excellence in 2017.

References

- Raharja A, Whitefield L. Clinical approach to vision loss: A review for General Physicians. Clinical Medicine. 2022;22(2):95–9. https://doi.org/10.7861%2Fclinmed.2022-0057

- World Health Organization. Blindness and Vision Impairment [Internet].; 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment [Accessed 17th December 2023].

- Falls [Internet]. NHS; 2021. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/falls/ [Accessed 7th December 2023].

- Rahman F, Zekite A, Bunce C, Jayaram H, Flanagan D. Recent trends in Vision Impairment Certifications in England and Wales. Eye. 2020;34: 1271-1278. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-0864-6 [Accessed 19th January 2024].

- Office for National Statistics. Disability, England and Wales: Census 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/disabilityenglandandwales/census2021 [Accessed 17th December 2023].

- The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Low Vision: the Essential Guide for Ophthalmologists (2021). p.5 Available at: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Low-Vision-Guide.pdf. [Accessed 7th December 2023]

- RNIB Key statistics about sight loss.2021. Available from: https://media.rnib.org.uk/documents/Key_stats_about_sight_loss_2021.pdf p.4, 6-7 [Accessed 20th January 2024].

- World Health Organization. International Classification of impairments, disabilities, and handicaps: A Manual of classification relating to the consequence of disease. 1980: p.27-29 Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/41003/9241541261_eng.pdf;jsessionid=AAF16467824A1845938FA6D9AF592EDF?sequence=1 [Accessed 7th December 2023].

- RNIB. Coming to terms with sight loss. Available from: https://www.rnib.org.uk/your-eyes/navigating-sight-loss/coming-to-terms-with-sight-loss/ [Accessed 20th January 2024].

- World Health Organization. Asia Pacific Low Vision Workshop. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/67744/WHO_PBL_02.87.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 20th January 2023].

- Lange R, Kumagai A, Weiss S, Zaffke KB, Day S, Wicker D, et al. Vision-related quality of life in adults with severe peripheral vision loss: A qualitative interview study - Journal of Patient-reported outcomes [Internet]. Springer International Publishing; 2021; 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-020-00281-y

- United Kingdom. National Assistance Act 1948: George V1. Chapter 29 Section 64: London: The Stationery Office; 1948.

- National Archives. Explanatory memorandum to – legislation.gov.uk. 2014. (2854): Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2014/2854/pdfs/uksiem_20142854_en_001.pdf p.3 [Accessed 18th January 2024].

- Publishing service.gov.uk. Certificate of vision impairment for people who are sight impaired. 2018. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6318b725d3bf7f77d2995a5c/certificate-of-vision-impairment-form.pdf [Accessed 20th January 2024].

- RNIB. The criteria for Certification. Available from: https://www.rnib.org.uk/your-eyes/navigating-sight-loss/registering-as-sight-impaired/the-criteria-for-certification/ [Accessed 20th January 2024].

- Department of Health. Care and support statutory guidance - GOV.UK. Dept of Health; 2014. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7f6122e5274a2e87db57f9/23902777_Care_Act_Book.pdf [Accessed 19th January 2024].

- RNIB. Getting help without registration. Available from: https://www.rnib.org.uk/your-eyes/navigating-sight-loss/registering-as-sight-impaired/getting-help-without-registration/ [Accessed 19th January 2024].

- Health and Social Care. Registering vision impairment as a disability. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-published-on-registering-a-vision-impairment-as-a-disability [Accessed 19th January 2024].

- Eyecare Wales. WGOS 3 – Low Vision Assessment-CVIW. Available from: https://www.nhs.wales/sa/eye-care-wales/wgos/eye-health-professional/wgos-3-low-vision-assessment-cviw/#:~:text=Certification%20of%20Vision%20Impairment%20Wales%20(CVIW)&text=Registration%20ensures%20access%20to%20services,CVIW%20also%20has%20additional%20functions. [Accessed 19th January 2024].

- RNIB. Starting Out Series – Benefits, concessions and registration; 2022. Available from: https://media.rnib.org.uk/documents/APDF-SE180905_Benefits_Concessions_and_Registration-v001_cCPrRtX.pdf P.39 [Accessed 20th January 2024].

- RNIB. Social Care and rehabilitation. Available from: https://www.rnib.org.uk/living-with-sight-loss/independent-living/social-care-and-rehabilitation/ [Accessed 21st January 2024].

- Macnaughton J. Low Vision Assessment. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann; 2005. p. 15, 18, 172-4.

- RNIB. Starting Out Series – Benefits, concessions and registration; 2022. Available from: https://media.rnib.org.uk/documents/APDF-SE180905_Benefits_Concessions_and_Registration-v001_cCPrRtX.pdf P.43 [Accessed 20th January 2024].

- RNIB. Starting Out Series - Benefits, concessions and registration; 2022. Available from: https://media.rnib.org.uk/documents/APDF-SE180905_Benefits_Concessions_and_Registration-v001_cCPrRtX.pdf P.45 [Accessed 20th January 2024].

- RNIB Key statistics about sight loss.2021. Available from: https://media.rnib.org.uk/documents/Key_stats_about_sight_loss_2021.pdf p.3[Accessed 20th January 2024].

- RNIB Key statistics about sight loss.2021. Available from: https://media.rnib.org.uk/documents/Key_stats_about_sight_loss_2021.pdf p.6-7[Accessed 20th January 2024].

- Macnaughton J. Low Vision Assessment. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann; 2005. p.18.

- Andrew N, Harsant R, Lawrence C. Low vision: An inter-professional approach. Canterbury: ABDO College; 2013. p.56-7, 61-3.

- United Kingdom. Children Act 1989 Elizabeth II. Chapter 41 Schedule 2. London: The Stationery Office;1989.

- United Kingdom. Care Act 2014 Elizabeth II Chapter 23 Section 77. London: The Stationery Office;2014

- Department of Health. Care and support statutory guidance - GOV.UK. Dept of Health; 2014. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7f6122e5274a2e87db57f9/23902777_Care_Act_Book.pdf p.378 [Accessed 19th January 2024].

- RNIB Key statistics about sight loss.2021. Available from: https://media.rnib.org.uk/documents/Key_stats_about_sight_loss_2021.pdf p.7 [Accessed 20th January 2024

- United Kingdom. Equality Act 2010. Ellizabeth II. Chapter2. Part 2. London: The Stationery Office; 2010.

- Department of Work and Pensions. Access to work factsheet for employers; 2023. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/access-to-work-guide-for-employers/access-to-work-factsheet-for-employers [Accessed 9th January 2024].

- NHS. Falls; 2021. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/falls/ [Accessed 7th December 2023].

- Age UK. Falls in later life: A huge concern for older people; 2019 Available from: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/latest-press/articles/2019/may/falls-in-later-life-a-huge-concern-for-older-people/ . [Accessed 7th December 2023].

- Ouyang S, Zheng C, Lin Z, Zhang X, Li H, Fang Y, et al. Risk factors of falls in elderly patients with visual impairment. Frontiers in public health. 2022; 10: 984199. https://doi.org/10.3389%2Ffpubh.2022.984199 [Accessed 7th December 2023].

- Lazarus R. What is low vision? [Internet]. Optometrist Network; 2020. Available from: https://www.optometrists.org/general-practice-optometry/guide-to-low-vision/low-vision/ [Accessed 20th January 2024].

- Macnaughton J. The Practical Management of Visual Impairment. Melton Mowbray: Clearview Training; 2018. p.20-21

- Swenor BK, Lee MJ, Varadaraj V, Whitson HE, Ramulu PY. Aging with vision loss: A framework for assessing the impact of visual impairment on older adults. The Gerontologist. 2019;60(6):989–95. doi:10.1093/geront/gnz117

- World Health Organisation. Programme on Mental Health WHOQOL User Manual. 2012. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/77932/WHO_HIS_HSI_Rev.2012.03_eng.pdf?sequence=1 p.11 [Accessed 17th December 2023].

- Langelaan M, de Boer MR, van Nispen RM, Wouters B, Moll AC, van Rens GH. Impact of visual impairment on quality of life: A comparison with quality of life in the general population and with other chronic conditions. Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 2007 Jan;14(3):119–26. doi:10.1080/09286580601139212

- Hernandez TA, Dickinson CM. The impact of Visual and Nonvisual Factors on Quality of Life and Adaptation in Adults with Visual Impairment. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2012;53(7):4234. doi:10.1167/iovs.12-9580

- Tseng Y-C, Liu SH-Y, Lou M-F, Huang G-S. Quality of life in older adults with sensory impairments: A systematic review. Quality of Life Research. 2018;27(8):1957–71. doi:10.1007/s11136-018-1799-2

- Elsman EB, Koel M, van Nispen RM, van Rens GH. Quality of Life and Participation of Children with visual impairment: Comparison with Population Reference Scores. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2021; 62(7):14. doi:10.1167/iovs.62.7.14

- Macnaughton J. Low Vision Assessment. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann; 2005. p. 173.

- Andrew N, Harsant R, Lawrence C. Low vision: An inter-professional approach. Canterbury: ABDO College; 2013. p.61.

- Kubler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. New York: Macmillian Books. Touchstone Books, New York; 1969

- Macnaughton J. The Practical Management of Visual Impairment. Melton Mowbray: Clearview Training; 2018. p.208

- Andrew N, Harsant R, Lawrence C. Low vision: An inter-professional approach. Canterbury: ABDO College; 2013. p.62-63.