The word ‘best’ conjures up a multitude of thoughts and feelings centred around high quality, proficiency, excellence and being unable to be beaten. The Oxford Learners Dictionary describes the word in various forms.1

Best (noun):

- The most excellent thing or person

- The highest standard that somebody/something can reach

- Something that is as close as possible to what you need or want

- The highest standard that a particular person has reached

It is interesting to note that this one small word can imply different things and have a subtly different bias depending on what context the word is used. The similar theme running through all definitions is that being ‘best’ is always associated with excellence or high achievement.

Regarding spectacle lenses, one only needs to read any optical journal or manufacturers lens catalogue to see that almost every company who produces spectacle lenses will claim somewhere within their literature that their offering is the ‘best’ or the ‘best in its category’, or best in the specific price range and so the list goes on.

As eye care professionals (ECPs) we must keep abreast of new innovations in spectacle lens design and in new products as they enter the market while keeping our core skills and knowledge up to date across the whole lens portfolio we have at our disposal.

For some patients, despite desiring the most recent innovation, we may find during the dispensing process that what they want may not be the ‘best’ product for them. Prescription constraints or facial characteristics may preclude specific optical appliances being of use to them.

As General Optical Council (GOC) registrants – whether optometrists, low vision opticians, contact lens opticians or dispensing opticians – our standards of practice clearly state that we must:

7.6 Only provide or recommend examinations, treatments, drugs or optical devices if these are clinically justified and in the best interests of the patient.2

This means that whatever lenses are dispensed, often after careful discussion with the patient about their specific prescription and lifestyle needs, registrants should dispense/prescribe what is correct for the patients’ particular needs and/or tasks, not what is, in the registrants’ opinion best.

Patients may of course desire something ‘better’ which of course they are absolutely entitled to however, careful discussion and contemporaneous record keeping must prevail in a case such as this.

Registrant opticians should be extremely careful not to fall into the trap of only recommending whatever lens they feel is best for a patient, or what is currently en vogue but comply with the standards of practice set by the regulator, lest they fall foul of these standards.

It should also be remembered informed consent is part of an on-going discussion and patients must be given information in a way they can understand with registrants applying professional judgement as to how this information is provided.3

This enables the patient to make an informed decision regarding the optimum optical device to suit their visual requirements.

Dispensing Approach

Many smaller or independent optical practices have little or no strategy or standard operating procedures (SOPs) for dispensing spectacles. In a corporate setting, SOPs are often seen as the norm with clear strategies and approaches in place.

Community optical practices are somewhat unique in that they ‘sell’ (prescribe/dispense) both optical services such as the testing of sight, the diagnosis and monitoring of ocular and systemic pathologies and/or disease and additionally the ‘sale’ of optical products (appliances) such as spectacle frames, spectacle lenses, contact lenses, ocular pharmaceuticals and products, low vision appliances, sports eyewear, protective eyewear to name but a few.

The marketing involved in selling services and product often varies with subtle differences in the language and emphasis employed to attract patients/clients to a particular practice.

Patients have specific expectations of the level of service they will receive, they consult us or return because they are confident that their expectations will be met or exceeded whether they consult us to avail themselves of the services we deliver or the products on offer – often it is both.

How a patient is made to feel is critical in their evaluation of our treatment of them. Not everyone will expect the same level of service, indeed, what is acceptable to one patient may fall way below the standards expected by another – there is a zone in which the level of tolerance will be tolerated with exceptional service at one end of the spectrum and poor at the other end of the spectrum. Good, adequate and could be better would lie somewhere in between.

In the book Services Marketing,4 Zeithaml and Bitner discuss customer expectations of customer service and highlight that everyone is different and expects different things when they purchase a service or indeed a product (see figure 1).

As ECPs we would do well to heed this observation and treat each and every patient as an individual and in accordance with the standards of practice set by the regulator and dispense and/or prescribe services and products which are justified.2

Should the patient wish to purchase anything in addition or if they perceive it to be better then detailed information should be provided to them and accurate recording of discussions and decisions made within the patient record.

Selecting the best lens – Quality

Any ophthalmic spectacle lens must adhere to several quality assurance checks and balances as well as satisfactorily adhere to the British Standards Institute (BSI) standards for production, processes and systems to ensure they will perform properly the function they are designed to do.

These standards apply from the time a product is conceived, through design, development, and manufacture, to testing for fitness of purpose and durability. Standards help improve safety and cost-effectiveness and save precious resources.

Standards have always been an important element for optical producers. UK trade and professional organisations have worked with the BSI, European Committee for Standardisation (CEN) and International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) to rationalise existing and new optical standards for semi-finished, uncut and glazed spectacles.6

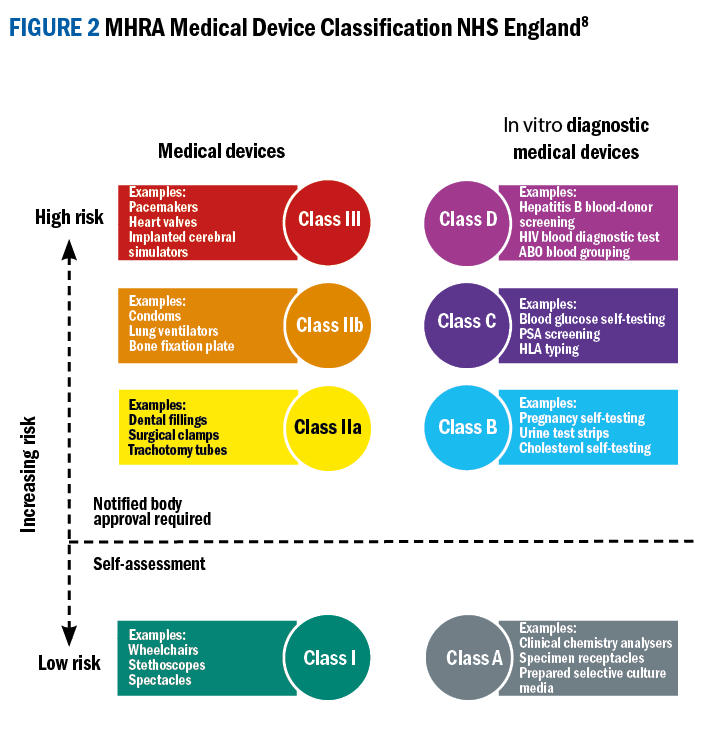

Standards go a long way to help ensure that optical products are of an acceptable quality. They provide consumers with assurance and benefits linked to working to a national or international standard. Spectacles are also a medical device and as such are subject to further regulatory standards contained within the medical devices regulations.7,8

Selecting the best lens – sales models

An internet search of the two words ‘sales models’ will return a multitude of models, examples and methodologies any optical practice may employ. Many ECPs believe, as professionals or clinicians, that sales are something they may never be associated with, however, most community optical practices derive the bulk of their turnover from the retailing of optical appliances such as spectacles, contact lenses and ancillary merchandise – in other words the sale of product.9

Many optical businesses in an effort to streamline their product offering, especially of spectacle lenses, adopt the Good, Better, Best sales model.9 This model offers suitable products at different price points that offer a lens that fulfils its purpose, an enhanced offering and a premium offering, which comprises the latest technology.

It can often be likened to the ranking in a race – bronze, silver and gold. A Harvard Business Review article by R Mohammed10 addresses the subject and explains how the model works across different sectors. Regarding spectacle lenses, if an optical practice adopts a Good, Better, Best sales model they offer products at entry level, which may persuade new patients to purchase from them.

The Better offering may resonate more with existing patients who see this product as offering good value for money and the product that is perceived as best is often regarded as the premium product available, often used for problem solving or for patients who always want the newest lens available and will usually be the clients with the latest technology and/or digital devices.

While this is a sound business model, practice owners would do well not to limit all lens choices to this model as often patients will require more than one pair of spectacles or may wish something outside of the normal lens catalogue. Flexibility to be able to offer each patient a truly bespoke pair of spectacles to suit their lifestyle or prescription needs, or, indeed more than one pair may fall outside this model.

Selecting the best lens – Two Case Studies

The following case studies show how selecting the best lens can be an arduous process and numerous factors must be considered. There is often no easy or quick fix, and each dispensing is as unique as the wearer of the finished spectacles.

Case Study 1

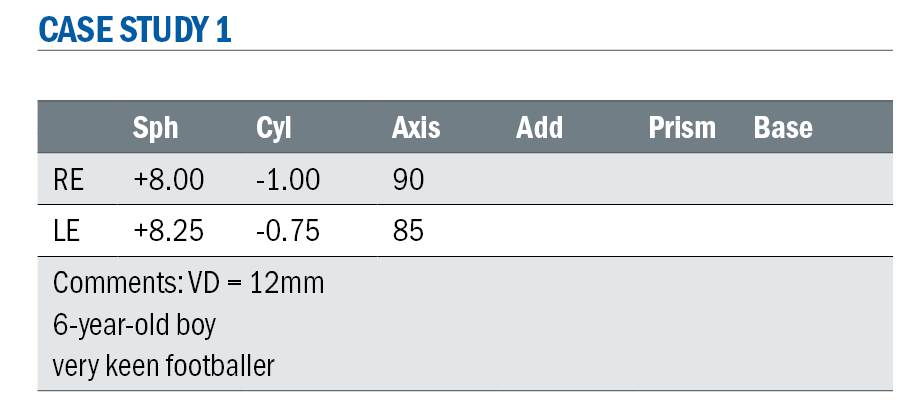

At first glance, looking at this prescription as a high plus, most ECPs would immediately be considering the best possible lens and discussing with the wearer what the most important aspects of their lenses and finished spectacles would be – the patient being six years old may hold no specific opinions on what they would like with regard to the lens but will almost certainly have a good idea as to what they would like their eyewear to look like.

The parents, however, may hold more rigid views on what they should be wearing.

Ultimately, as a medical device, the best possible visual acuity would be desired, other factors that would be important would be the comfort of wearing spectacles with a prescription such as this, minimising the weight and thickness of the lenses would be a huge consideration, as would eye protection (gym/school/football) and durability (scratching/ damage).

When faced with a high plus Rx lens options are numerous – high refractive index and aspheric lenses in plastics materials would render the prescription thinner, flatter and lighter. High index lenses with ever more sophisticated lens treatments will protect against surface scratches and make them easier to clean.

From a safety point of view mid-index, such as trivex or polycarbonate lenses, will be more robust and less likely to break.

Considering all these aspects, which lens would be best? Without additional information such as the size of the child, the frame chosen, the centration distance of the lenses, lens blank size and availability and fit of the chosen frame it is impossible to answer that question.

With the advent of free form technology and CNC surfacing the stocking of different blank sizes of finished and semi-finished lenses is reduced, however, many high index lenses are still stocked in 65mm or 70mm blank sizes.

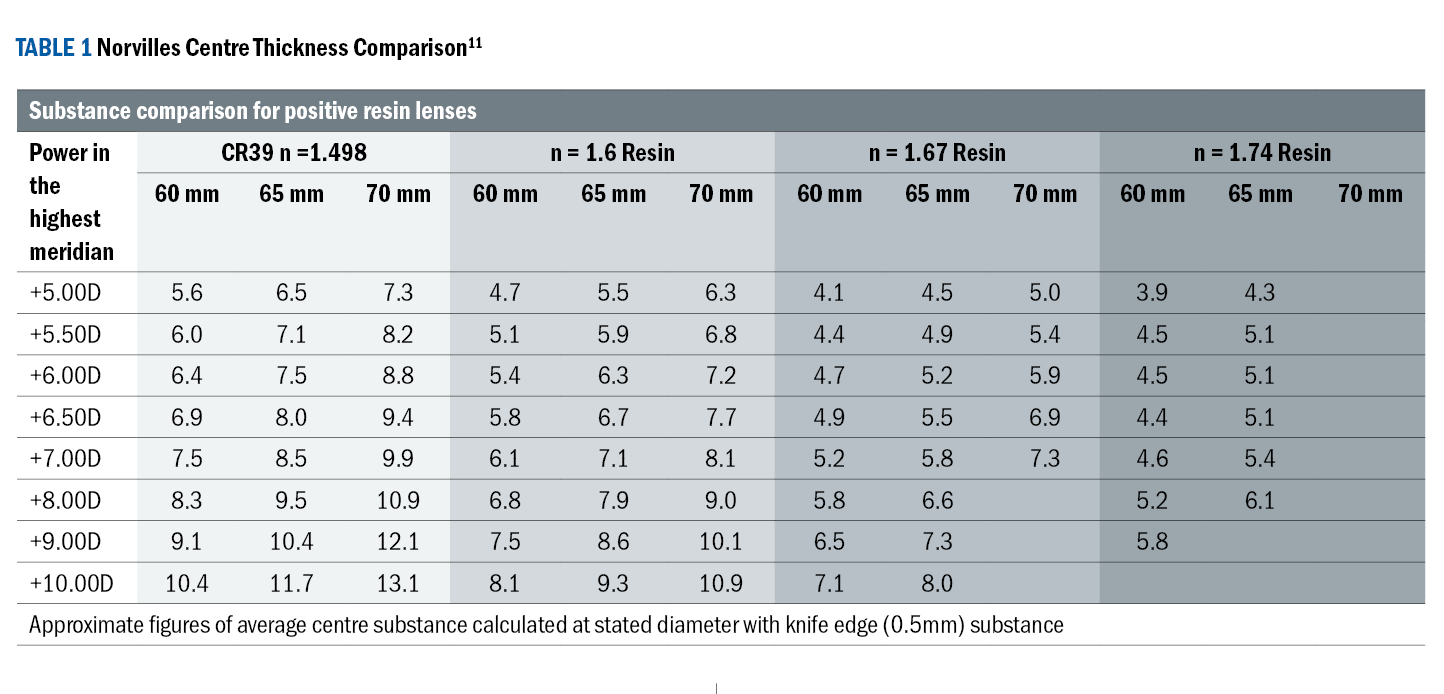

The challenge then faced is a large decentration of the optical centre of the lens to match the measured centration distance of the lenses resulting in a thicker, heavier lens than may be produced by surfacing a smaller blank in a standard material which would require less decentration to achieve the desired result, see table 1.

If the following lens indices and thicknesses are compared- what may be considered the best may indeed not be. If we look at all indices in a 65mm blank for a +8.00D lens the 1.74 centre thickness is 6.1mm, 1.67 is 6.6mm, 1.6 is 7.9mm and 1.498 is 9.5mm much as we would expect.

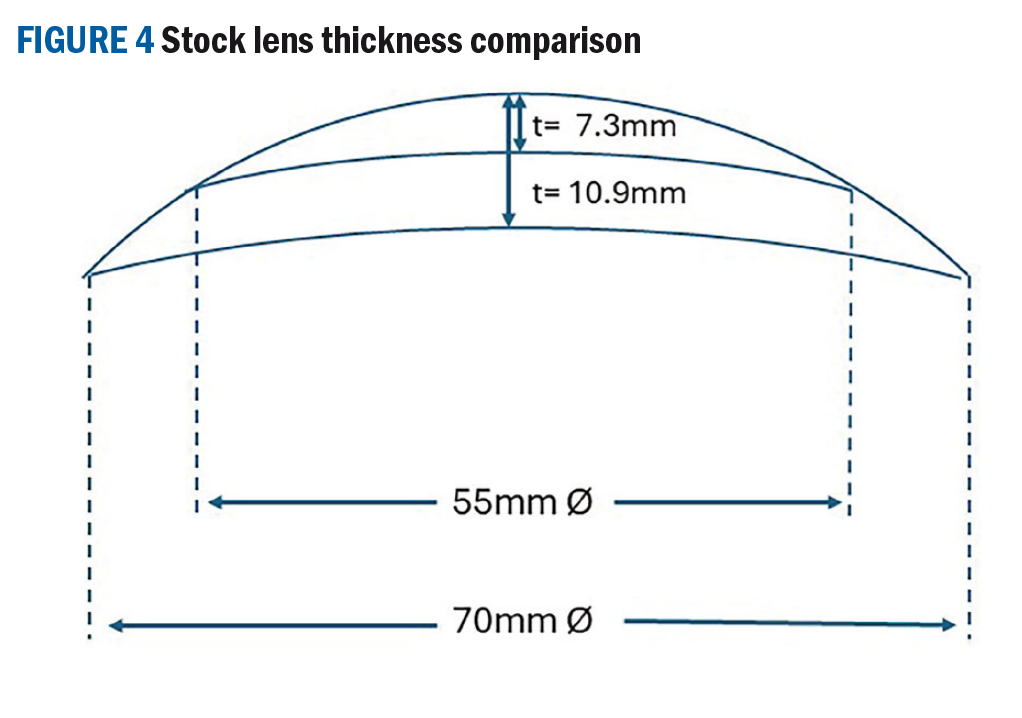

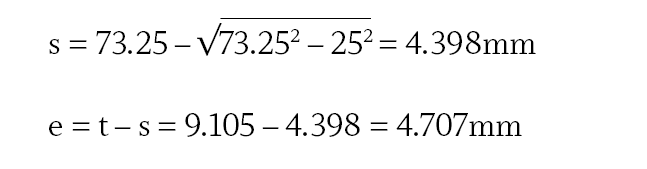

This table does not show expected centre thicknesses for 55mm or 50mm blanks (which are available) and if we extrapolate the figures in 1.498 index to include these, then the expected centre thickness would be somewhere around 7.3mm for the 55mm blank and 6.5mm for the 50mm blank which is roughly the centre thickness of 1.67 index in a 65mm blank (see figure 4).

The advantage of surfacing a small blank is that the cost to the practice and patient will be less than the high index lens and coatings. Also if the decentration is minimal the cosmetic appearance of the smaller blank may be better than the higher index lens which may see increased nasal edge thickness.

The advantage of surfacing a small blank is that the cost to the practice and patient will be less than the high index lens and coatings. Also if the decentration is minimal the cosmetic appearance of the smaller blank may be better than the higher index lens which may see increased nasal edge thickness.

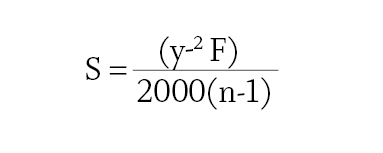

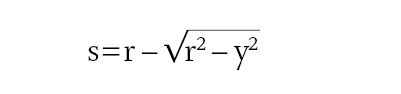

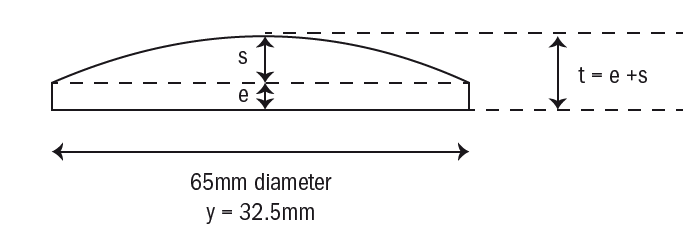

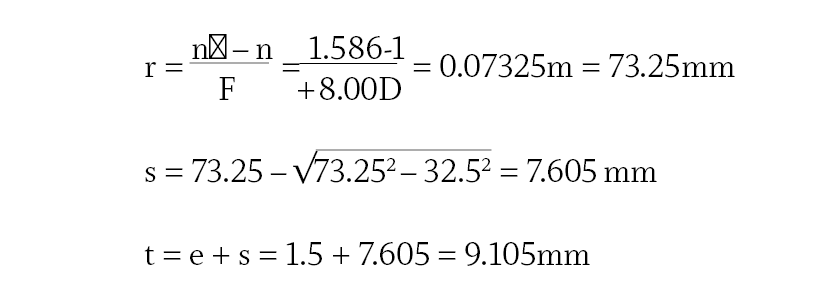

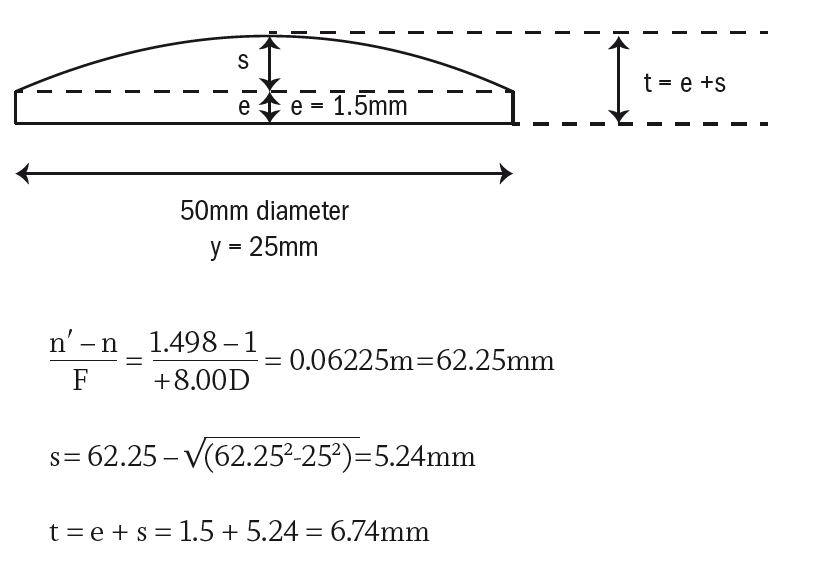

It should not be forgotten that lens thickness can also easily be calculated using sags. There are two formulas that can be used:

Approximate sag formula

The approximate sag formula is simpler mathematically but considering today’s technology, calculators are easily accessible via a smart phone it is just as easy to use the accurate sag formula.

Accurate sag formula

If we take the example of a plano-convex +8.00D lens made in CR39 (n = 1.498) surfaced to 50mm MSU edge thickness1.5mm and a mid-index polycarbonate lens (n = 1.586) stock 65mm diameter uncut.

Polycarbonate stock 65mm lens

CR39 50mm MSU

Consider the effect of edge thickness of edging down a stock polycarbonate lens.

The edge thickness for polycarbonate is over three times thicker than CR39.

It is clear that a stock polycarbonate lens has a greater centre substance than the surfaced CR39 lens, but the real thickness will be considerably worse once the stock lens is edged down to fit the chosen frame.

This example highlights the difference between using a stock and surfaced lens, careful consideration should be given to recommending higher refractive index lenses on the basis that they are thinner and lighter as we can see this is not always correct.

The NHS Small Glasses Supplement (SGS) should not be overlooked as high positive powered lenses surfaced to minimum substance are accepted as an extensive adaption and fits one of the two qualifying criteria, the other being that the boxed centre distance is not more than 55mm.12

Considering the protection aspect of the spectacles, a full rim plastics frame would be a good choice or an additional dispense of a sports frame with silicone inserts at the bridge and temples to absorb impact if there is a clash of heads or a high boot.

Conventional wisdom would suggest that an impact resistant material such as trivex or polycarbonate which is inherently stronger would be advisable, however, the Rx is plus and the centre thickness increased, so breakage of the lens is unlikely.

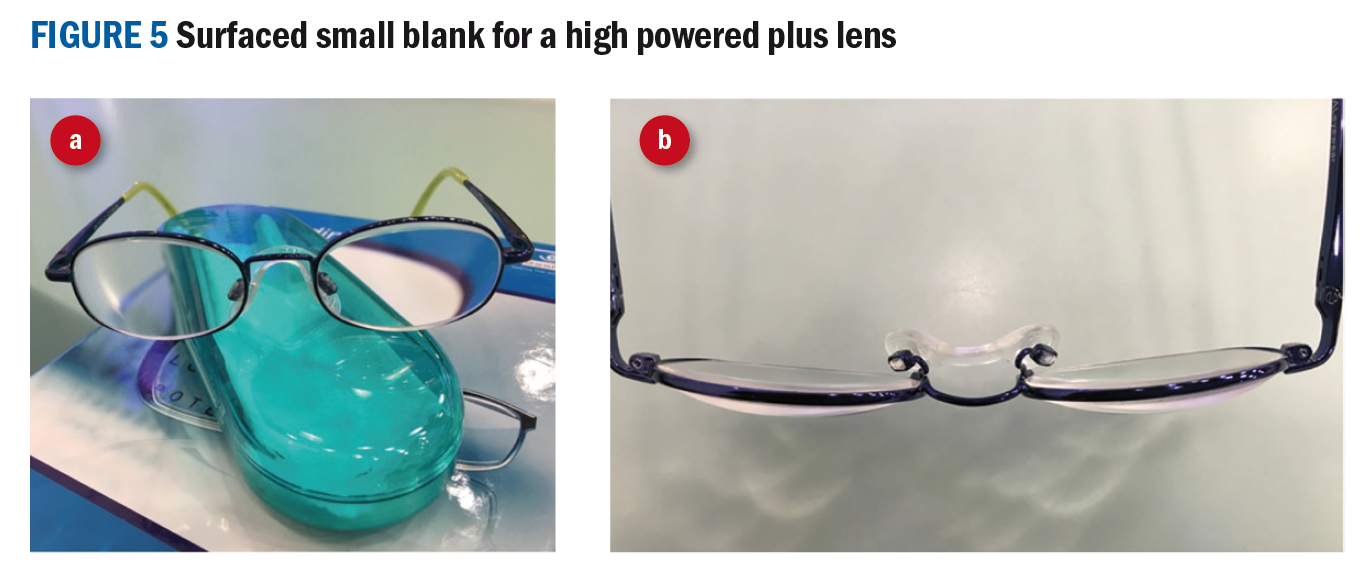

An example of using a surfaced small blank size for a high powered plus lens (Rx R. +10.00/-1.00 85 L. +10.25/-1.75 90) is shown in figure 6.

As stated earlier, GOC standards of practice set out expected standards of behaviour for registrants - only recommend lenses that are clinically justified,2 and provide clear information to enable patients and parents to make an informed decision on the lens that best suits their individual needs.

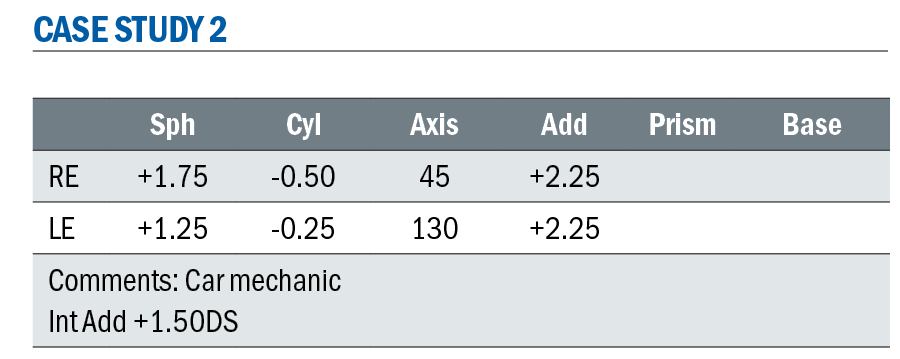

Case study 2

When faced with dispensing a prescription like this, most ECPs would discuss at length the patients’ requirements. Given the occupation perhaps everything this patient requires will not be able to be incorporated in a single pair of spectacles; he may need to be dispensed an additional pair for work.

Too often we are challenged to give the person the best we can, but often the best may be a pair for every day and a separate pair for specific tasks.

Most manufactures of progressive power lenses will advocate that their premium lenses will be the only pair you will ever need, however, specific occupations – such as car mechanics require a significant number of detailed tasks above head height – also consider librarians, pharmacists, joiners, electricians’ painter and decorators and a whole host of other occupations.

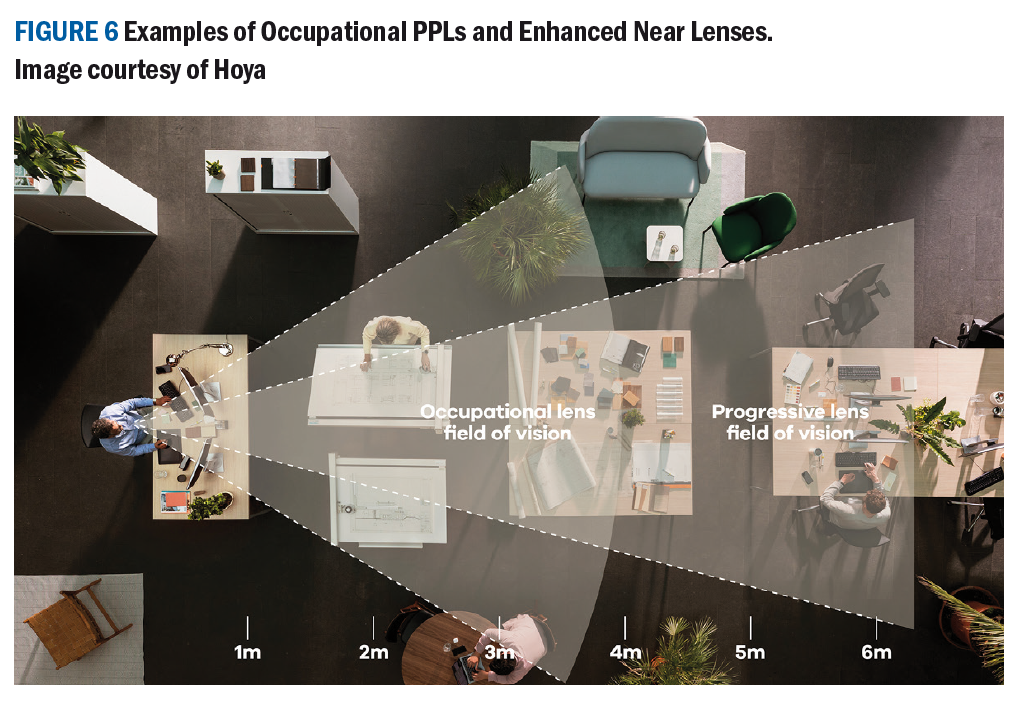

Most PPLs have the distance portion at the top of the lens and progress gradually through intermediate to near at the bottom – not ideal when working above head height – even specific occupational progressive lenses may not address this requirement adequately.

Most manufacturers offer occupational PPL and enhanced near lenses, however, for a car mechanic these may not be the best solution as in all these lenses, the intermediate and near portions of the lens are towards the bottom of the lens and this patient requires his intermediate or reading at the top.

The nature of the work will also require the patient to walk around and potentially select tools or access a diagnostic computer to work on newer vehicles, so a near portion may also be required.

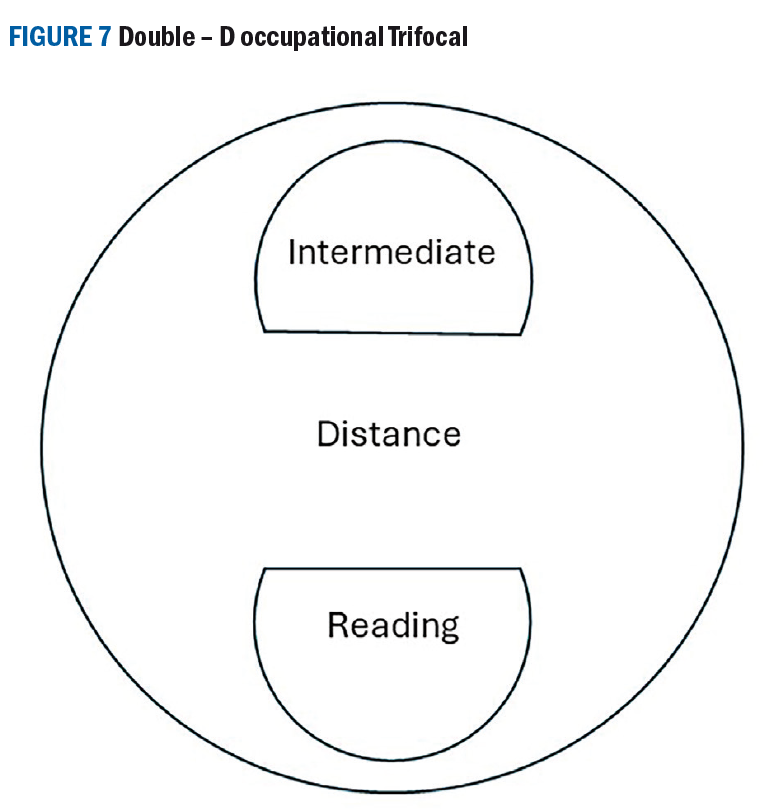

A lens which may be the best for this specific case may be an occupational double-D trifocal. Seldom used, but a helpful solution for many occupations. It may not be the most attractive lens on the market, yet optically it performs very well and helps overcome many obstacles faced by some occupations and professions.

Typically, the Double-D (28mm segment diameters) occupational trifocal has the distance portion in the middle of the lens, a D segment with the intermediate Rx at the top and a D segment with the near Rx at the bottom. The intermediate portion is usually 60% of the full near add for most manufacturers.

Conclusion

Uncovering the best lens for patients is not an easy task – there are many aspects to consider and as ECPs we should not be influenced by sleek advertising claiming products to be the ‘best’ without careful consultation with our patients as to their needs and wants.

The product that is best for them may not be the latest, most expensive, or most coveted, but the one that performs best for them or is the most comfortable in a certain situation.

Often the simplest solution is the most effective one and the one that alleviates any issues a patient may be experiencing, and the optician or optometrist who finds the solution is repeatedly held in high regard by the patient and recommended to friends and colleagues.

- Fiona Anderson BSc(Hons) FBDO R SMC(Tech) FEAOO is past president of the International Opticians Association, ABDO past president, past chair Optical Confederation, Optometry Scotland member, past Grampian AOC member, EAOO – co-opted trustee, ECOO European Qualifications board member, Renter Warden: Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers, Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers Liveryman & Fellow of the European Academy of Optometry & Optics.

References

- Oxford University Press. Oxford Learners’ Dictionaries, best. Available from: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/best_3#:~:text=the%20most%20excellent%20thing%20or%20person [Accessed 25th March 2024]

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians, Supplementary guidance on consent. London: General Optical Council 2016. P 12.

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. London: General Optical Council 2016. P 8.

- Zeithanl V, Bitner J. Services Marketing 3rd Edn. New York: Irwin McGraw-Hill. 2003 p 66

- Zeithaml VA, Berry LL, Parasuraman A. The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. Journal of the Academy og Marketing Science. 1993; 21: 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070393211001

- Wakefield K. Bennett’s Ophthalmic Prescription Work 4th Edn. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann Ltd;2000.

- GOV.UK. Factsheet: medical devices overview. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/medicines-and-medical-devices-bill-overarching-documents/factsheet-medical-devices-overview#:~:text=A%20medical%20device%20is%20any,contact%20lenses%20and%20breast%20implants. [Accessed 20th March 2024]

- NHS England. Medical devices and digital tools. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/medical-devices-and-digital-tools/#:~:text=A%20medical%20device%20is%20any,or%20treating%20a%20medical%20condition. [Accessed 20th March 2024]

- Mintel Group Ltd. UK Optical Goods Retailing Market Report 2023. Available at: https://store.mintel.com/report/uk-optical-goods-retailing-market-report [Accessed March 20, 2024]

- Mohammed R. The Good-Better-Best Approach to pricing. Harvard Business Review. 2018; September -October. Available at: https://hbr.org/2018/09/the-good-better-best-approach-to-pricing [Accessed 20th March 2024]

- Norville Group. Prescription Companion. P.135. Available at: https://www.norville.co.uk/user/lens_catalogues/pdfs/Companion%2025518.pdf [Accessed 20th March 2024]

- Association of British Dispensing Opticians. Making Accurate Claims 2022. Available at: https://www.abdo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/MACE-guide-2022.pdf [Accessed 20th March 2024]