‘And are you a driver?’ This question is asked for nearly every adult patient attending an eye examination, often as a delegated task. What do we do with this information? If the information is collected, then we need to do something with it. Advice to every driver (and potential drivers) about their visual fitness to drive should be included at the end of the examination.

Unfortunately, with an increasing number of our older patients this can be a difficult conversation to have. This article will consider the visual acuity requirement only for Group 1 drivers, although the visual field requirements also need to be met. The vision standards for Group 1 drivers in the UK refer to binocular vision, so visual acuities stated in this article relate to those measured binocularly.

Current UK driving standards

The ‘number plate test’ has been in use in the UK since 1935 and the ability to correctly read a number plate has been part of the practical driving test since 1965. Since the change of number plate format in 2001, the requirement is to correctly read a number plate from 20 metres in ‘good daylight’ for Group 1 drivers.1

Advantages of using a number plate as an acuity test for drivers include its convenience and accessibility, meaning that it can be used by driving test examiners, police, and drivers themselves. Disadvantages include the variable difficulty of letter and number combinations, variable outdoor lighting conditions and dirt on the number plate.

The ability to correctly read a number plate is assessed at the start of the practical driving test and normally three attempts with different plates are allowed. As this is conducted outdoors using parked cars, the distance may not be exact, however, examiners are required to check the distance with a tape measure for a third and final attempt.2

A number plate acuity test has been used in the past in other countries, although others require visual acuity measurement with standard test charts. This variable approach to determining acuity for driving standards across Europe lead to the introduction of an EU directive on driving licensure in 20063 and a ‘test chart’ visual acuity of 6/12 (0.30 logMAR) was added to the DVLA regulations in May 2012.

Drivers holding a UK licence can drive in the EU and European Economic Area, and vice versa. The regulations refer to ‘visual acuity of at least decimal 0.5 (6/12) measured on the Snellen scale’.1 There is no guidance on test chart format or testing distance.

An important yet inconvenient point is that drivers must meet the number plate requirements and the ‘Snellen scale’ acuity of 6/12. The wording used across various DVLA publications and websites is ‘you must also’.1 So, we have the challenge of not only advising our patients on their visual fitness to drive but also the need to achieve two vision standards, which are not directly comparable. In the test room, we will know if they can achieve one part of the standard, but we will not know that they can achieve both.

What are the differences between the two tasks?

For years prior to the addition of the 6/12 requirement, optometrists have grappled with the problem of a test chart visual acuity, which could be considered equivalent to the number plate. Many of us have been taught (or think we have been taught) that a visual acuity of 6/10 or 6/9-2 is equivalent to the number plate and that achieving this means the patient should meet the driving vision standards.

This arises from the study by Drasdo and Haggerty4 in 1980 which extrapolated from data to determine an equivalent Snellen acuity that would fail the same proportion of individuals. In addition, the format of the number plate used in the study had different stroke width and spacing than current post-2001 versions.

A number of test charts include a mock of a number plate for use in the test room but there will still be differences between these and the actual number plate task conducted at 20 metres and in an outdoor environment. The current (post-September 2001) layout for UK number plates includes the use of the Charles Wright 2001 typeface with figures that are 79mm high and 50mm wide with a stroke width of 14mm.

Inter-figure spacing is 11mm (see figure 1) and overall plate dimensions are typically 520mm x 111mm.5 At the testing distance of 20 metres, this gives the stroke width of the figures an angular subtense of approximately 2.4’ which would correspond to the stroke width of a 6/14.4 Snellen optotype.

Figure 1: UK number plate typeface and layout

Pre-2001 number plates have slightly different dimensions and spacing. The proportions of the figures on the number plate are different to test chart optotypes, having a height to width ratio of 1.58 compared to 1.20 for British letters (5 x 4), which would be found on a typical Snellen chart in the UK and 1.00 for Sloan letters (5 x 5), such as found on the ETDRS logMAR charts.

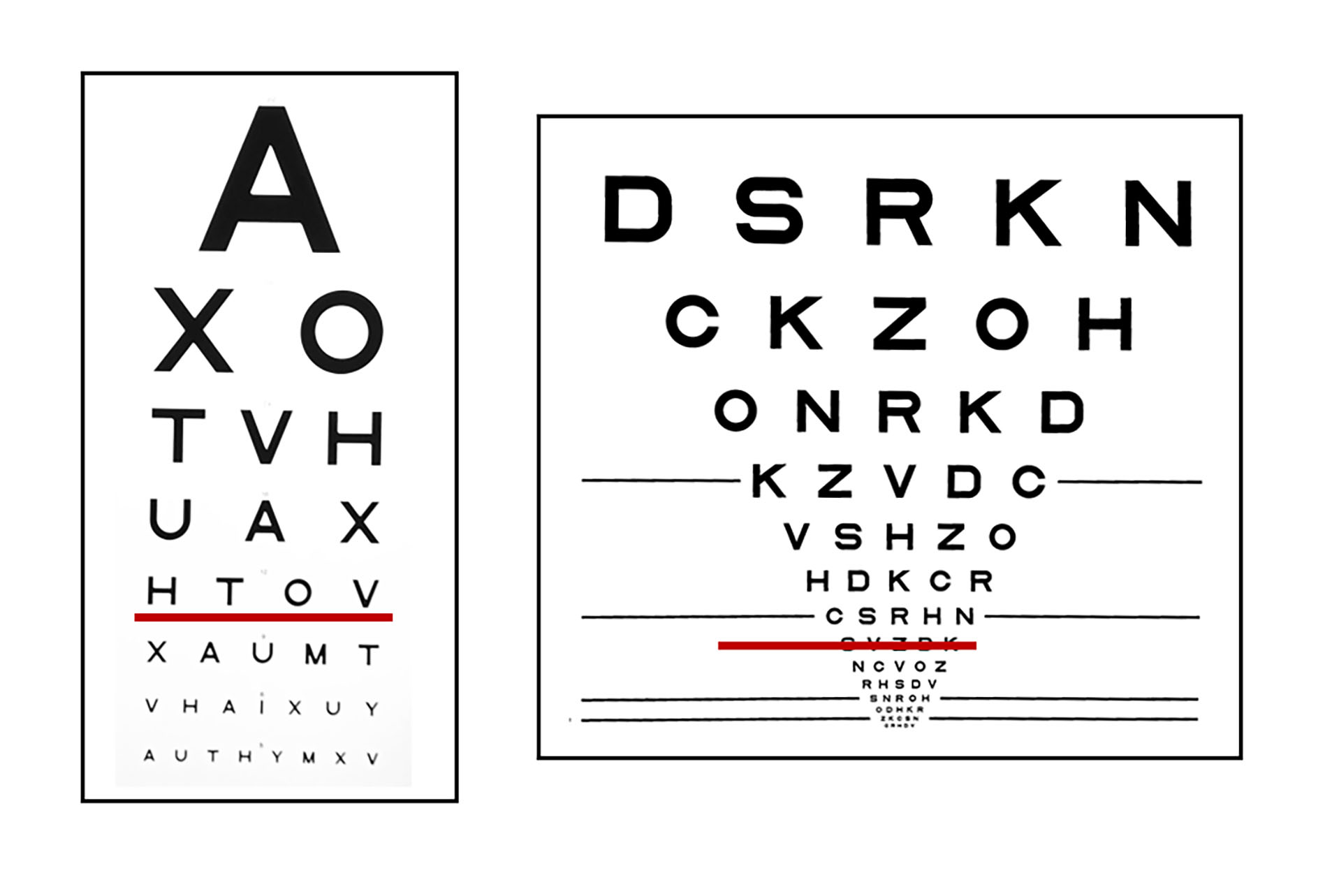

The 11mm spacing between the figure is closer than that found on most test charts (figure 2) at around 1/5th of the letter width giving greater crowding, which would increase the difficulty of the task. The number of letters per line and inter-letter spacing will also vary between test chart designs, but at an acuity of 6/12, the differences are often less than at higher or lower acuity levels and the number of letters per line are similar (figure 2).

Figure 2: Commonly found test chart designs in UK practices. Snellen chart on the left and ETDRS logMAR chart on the right, with the 6/12 line underlined in red

Other task differences include the lighting of the test chart and number plate. The majority of test charts used in optometric practices will be internally illuminated or screen based, whereas in other settings such as GP practices they are likely to be externally illuminated paper charts.

The illuminance of the testing environment will differ, with 500-1,000 lux typical in the indoor setting whereas in the outdoor setting for the number plate test this can vary between 1,000 lux in overcast conditions to 100,000 lux in bright sunlight. Any dirt on the number plate would reduce the contrast and so affect the difficulty of the task.

Can the two tasks be compared?

An alternative approach to the problem of comparing the two driving vision requirements is to establish an acuity cut-off where we can reasonably expect the number plate to be correctly read. A study by Latham et al6 aimed to establish acuity ranges where both tasks would be passed, both failed, or one task passed but one task failed, for two different test chart formats (Snellen and ETDRS).

The Snellen chart was scored to the nearest whole line and the ETDRS chart was scored on a letter-by-letter logMAR notation. For 120 participants who were free from ocular disease but not wearing any required refractive correction for distance, an ‘overlap zone’ where there was uncertainty that both the number plate and 6/12 would be achieved was established.

For the optometrist tasked with advising their patient on visual fitness to drive, it is the lower end of this overlap zone which is of interest as this gives an acuity level at which we can be confident that the number plate would be correctly read. For the Snellen chart scored to the nearest whole line seen correctly, all participants with a visual acuity of better than 6/9 could correctly read the number plate.6

This means that for any individual achieving 6/9 or 6/12 we cannot be certain that they will correctly read the number plate.

The ETDRS chart scored letter-by-letter, all participants with a visual acuity better than +0.12 logMAR (6/7.5 -1) could correctly read the number plate.6

Between these values (and including 6/12 or +0.30 logMAR), we cannot be certain that the number plate would be correctly read although, the number of individuals with acuities between these cut-off values and 6/12 who were unable to correctly read the number plate was small.

A further group of participants could not achieve 6/12 but did correctly read the number plate. These individuals would be less of a challenge to advise in practice, as both standards have to be met. However, for the majority of patients where there is uncertainty about their visual fitness to drive, it is as a result of ocular disease rather than uncorrected refractive error.

Ocular disease and notifiable conditions

A bigger concern is visual fitness to drive in the presence of ocular disease and in particular those conditions which are likely to be bilateral, chronic and progressive, such as cataract, glaucoma and macular degeneration. As practitioners working in primary care, optometrists will often be ‘case-finding’ for these common and often progressive conditions.

We will commonly encounter patients with reduced acuity due to ocular disease where the acuity is approaching or beyond the driving standard of 6/12 and in many cases the patient may be managed in the practice rather than referred for the condition at this stage. This situation will most often be encountered in our older patients.

DVLA reports that the number of people aged 70 years and above holding full driving licenses increased by nearly a quarter between 2016 and 2020 to over 5.6 million.7 This makes up 14% of all UK driving licences and 62% of those age 70 years and above hold a full driving license.

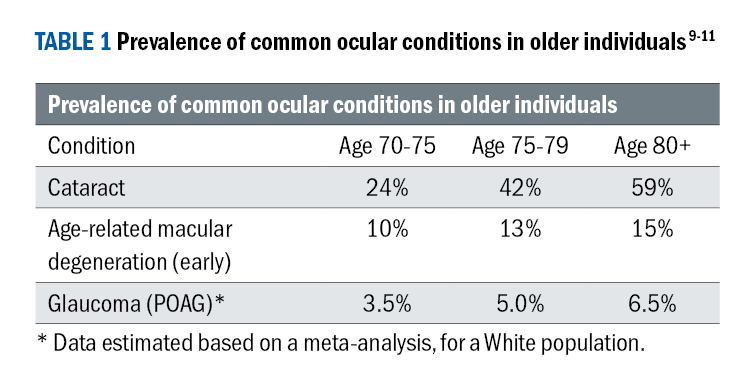

On reaching age 70 years, drivers have to apply for license renewal and every three years thereafter.8 A self-declaration relating to vision and medical conditions forms part of the application. The prevalence of some of these common conditions in older age groups is summarised in table 1.9-11

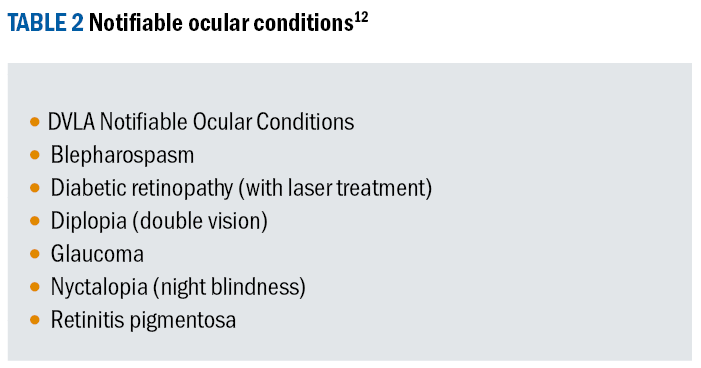

There is a group of ocular conditions listed by the DVLA12 that the license holder must report (see table 2). A fine of £1,000 may be imposed for failure to report and it is worth noting that this fine relates to reporting irrespective of whether the vision standards can be met. The list does not include macular degeneration or cataract and there are additional notifiable conditions for group 2 drivers.

Contrast sensitivity, glare and vision standards for driving

Many of these common ocular conditions will have an impact on contrast sensitivity (CS) as well as visual acuity. This may widen the difference in performance between the two driving vision tasks, Rae et al.13 investigated the over-lap range between the number plate and test chart standards in the presence of reduced CS.

With simulated reduced CS, compared to uncorrected refractive error alone, a Snellen chart whole line acuity of better than 6/12 or an ETDRS letter-by-letter score of better than +0.08 logMAR (6/7.5 + 1) needed to be achieved to predict that the number plate would be correctly read.

In addition, there was a higher number of participants with VA between these values and 6/12 who could not correctly read the number plate, compared to refractive blur alone. So, we can be less certain that a patient who can see 6/12 would also correctly read a number plate in the presence of reduced CS.

Data from the Blue Mountains Eye Study14 shows that both early posterior sub-capsular and cortical cataract significantly reduce CS at intermediate and high spatial frequencies. A study of patients with maculopathies and visual acuity better than 6/9 showed poorer CS thresholds across a range of spatial frequencies.15

For patients with glaucoma, a reduction in Pelli-Robson CS in patients with moderate VA reduction has also been demonstrated.16 For patients with these conditions who may meet the VA standard, the addition of reduced CS will increase the uncertainty that they will also be able to correctly read the number plate.

The European Directive of 20062 does not directly state a standard for CS but referred to the consideration of CS and glare by ‘a competent medical authority’ where there is doubt about the ability to achieve the driving standard. Disability glare will also increase in the presence of cataract due to light scatter.

Unlike CS, the Blue Mountains study14 did not show a clear trend between cataract severity, type and glare disability although the presence of cataract did increase glare disability. This aspect of visual function is less easily tested clinically compared to CS. Glare disability has been shown to affect outdoor and indoor visual function to different extents,17 so it would be expected that this would also add to the numbers of patients who can achieve one but not both driving vision standards.

Advising the patient who is a driver

Having reviewed the standard, we can see that there will be a variety of situations that may need to be discussed (and recorded) in the eye examination of any patient who is a driver.

Awareness of the vision standards for driving

A survey conducted for DVLA in 202118 showed that just under half of drivers questioned were aware of the correct distance for the number plate test. The press release for the ‘Number Plate Test campaign’19 highlights the need for drivers to regularly self-test and it also gives advice on estimating the testing distance as approximately five car lengths or the width of eight parking spaces. The advice also included a two-yearly eye test or sooner if any change to vision is noticed.

Uncorrected refractive error

When the test chart visual acuity is at least 6/7.5, we can be confident that the number plate standard would also be achieved. Where acuity between 6/7.5 and 6/12 can be achieved with the refractive correction, the patient should be advised to wear the correction for driving and also to self-check the number plate. Where refractive correction is needed to meet the driving vision standards, the patient should be reminded that this should aways be worn when driving and this advice clearly annotated in the patient record.

Presence of notifiable ocular conditions

When a notifiable ocular condition is present, the patient needs to be advised of this and that DVLA must be informed via the V1 form, even if the driving vision standards are met.20 Patients should be advised that they may still be able to continue driving, but that failure to report can lead to a £1,000 fine.

Test chart acuity of 6/12 met in the presence of an ocular condition

If we have noted the presence of ocular conditions that may affect CS, such as cataract, glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration, then we need to be aware that this increases the likelihood of the number plate test not being achieved where the test room acuity falls between 6/7.5 and 6/12.

The patient must check the number plate and inform DVLA if this cannot be seen. Where a progressive condition is present, advice on a suitable recheck interval should be given. It may be helpful to also have the conversation about ‘next time’ so the patient can start thinking about stopping driving in the future, rather than this coming as a shock in a future appointment.

Once again this must be annotated in the patient record and visible at future consultations for all eye care professionals.21

Test chart acuity of 6/12 not met

If 6/12 in the test room cannot be met, even with best refractive correction, then the patient does not meet the driving vision standards, irrespective of whether they can correctly read a number plate. The advice that they do not meet the standard must be clear and noted in the patient’s record.

The patient needs to be informed that they must notify DVLA and advised of the £1,000 fine for non-reporting and that insurance may no longer be valid. Where resistance from the patient is met, a written statement about their failure to meet the standard can be issued.

The DVLA also has a useful short summary of the standards and reporting procedures, which can be printed out and kept in the practice to give to patients.22 Being aware of local council transport options for the older patient can be useful, such as free bus passes. In some areas, the bus pass can be exchanged for annual taxi vouchers.

Choice of language

Where the vision standards for driving are not met, the optometrist should be aware of the language they use when explaining this to the patient.

While wanting to be supportive and empathetic towards the patient, we still need to avoid using words or phrases that could leave some doubt in the patient’s mind as to whether they can drive, such as ‘ideally’, ‘shouldn’t really’, ‘may not’, ‘not quite up to standard’.

Eye care professionals have a duty of care to protect and safeguard patients from harm including to communicate effectively with patients when their vision no longer meets driving standards.23,24

Summary: practitioner and patient responsibilities

Practitioner

- Check and record best-corrected binocular distance visual acuity

- Advise if the patient is likely to meet both standards, may not meet both standards or if the test chart standard has not been met

- Advise the patient of the presence of any notifiable ocular

condition - Make the patient aware of progressive conditions

Patient

- Self-check the number plate test regularly

- Have an eye examination every two years or sooner if advised to, or if a change in vision is noticed

- Report notifiable conditions and / or if they have been advised by an optometrist or medical practitioner that the 6/12 standard has not been met.

- Sheila Rae graduated in ophthalmic optics from UMIST and spent several years in community optometric practice, undertaking pre-registration supervision as well as College of Optometrists examining and assessing. She completed a PhD at Anglia Ruskin University on myopia control and has been a full-time lecturer in optometry for 17 years. She is currently programme leader for the Master of Optometry programme at the University of Hertfordshire and has research interests in refractive error development, visual function and binocular vision.

References

- GOV.UK (2024). Driving eyesight rules. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/driving-eyesight-rules [Accessed 24/01/2024].

- GOV.UK (2022) Understanding your driving test result. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/understanding-your-driving-test-result/car-driving-test [Accessed 24/01/2024].

- European Parliament. Commission Directive 2006/126/EC of 20 December August 2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on driving licences. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:403:0018:0060:EN:PDF

- Drasdo N, Haggerty C.M. A comparison of the British number plate and Snellen vision tests for car drivers. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 1981; 1(1): 39-54.

- The Road Vehicles (Display of Registration Marks) Regulations. 2001. SI 2001/256. London. The Stationery Office;2001.

- Latham K, Katsou M.F, Rae S. (2015) Advising patients on visual fitness to drive: implications of revised DVLA regulations. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 99: 545–548.

- GOV.UK (2020). Reported road casualties Great Britain: older drivers factsheet 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/

government/statistics/reported-road-casualties-great-britain-older-driver-factsheet-2020/reported-road-casualties-great -britain-older-drivers-factsheet-2020#:~:text=In%202020%2C%20there%20was%20a,to%2035.7%25%20for%20all%20drivers. [Accessed 24/01/2024]. - GOV.UK. Renew your driving licence if you’re 70 or over. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/renew-driving-licence-at-70 [Accessed 27/03/2024].

- NICE (2022). Cataracts: How common is it? Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cataracts/background-information/prevalence/#:~:text=About%203%20in%2010%2C000%20children,by%2015%20years%20of%20age [Accessed 24/01/2024].

- Colijn, J. A. et al. (2017). Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in Europe. The past and the future. Ophthalmology 124: 1753-1763.

- Rudnika A.R, Mt-Isa S, Owen C, Cook D.G. Variations in primary open-angle glaucoma prevalence by age, gender, and race: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2006; 47(10): 4254-4260. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.06-0299

- GOV.UK (2024). Eye conditions and driving. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/eye-conditions-and-driving [Accessed 24/01/2024].

- Rae S, Latham K, Katsou M. Meeting the UK driving vision standards with reduced contrast sensitivity. Eye. 2016; 30: 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.188

- Chua B, Mitchell P, Cumming R. Effects of cataract type and location on visual function: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Eye. 2004; 18: 765–772. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701366

- Wai K M, Vingopoulos F, Garg I. Kasetty M. Contrast sensitivity function in patients with macular disease and good visual acuity. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2022; 106(6): 839-844.

- Richman J, Lorenzana LL, Lankaranian D, Dugar J. Importance of visual acuity and contrast sensitivity in patients with glaucoma. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2010; 128(12): 1576-1582. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.275

- Abrahamsson M, Sjostrond J. Impairment of contrast sensitivity function (CSF) as a measure of disability glare. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1986; 27(7): 1131–1136.

- GOV.UK (2021). Under 50% of motorists are aware that they must read a number plate from 20 metres, figures show. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/under-50-of-motorists-aware-they-must-read-a-number-plate-from-20-metres-figures-show [Accessed 24/01/2024].

- GOV.UK. DVLA asks drivers to look again in new EYE 735T campaign. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/dvla-asks-drivers-to-look-again-in-new-eye-735t-campaign#:~:text=Drivers%20will%20be%20encouraged%20to,number%20plate%20from%2020%20metres. [Accessed 27/03/2024].

- GOV.UK. Report your medical condition (formV1). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/v1-online-confidential-medical-information [Accessed 27/03/2024].

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians, 8.1 Maintain adequate patient records. London: General Optical Council; 2016 p13

- GOV.UK (2024). A guide to standards of vision for driving cars and motorcycles (Group1). INF 188/1. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a81cd49ed915d74e6234305/inf-188X1-standards-of-vision-for-driving-cars-and-motorcycles-group-1.pdf [Accessed 24/01/2024].

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians, 11. Protect and safeguard patients, colleagues and others from harm. London: General Optical Council; 2016 p11

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians, 2. Communicate effectively with your patients. London: General Optical Council; 2016 p7