This is part one of a two-part series focusing on clinical presentation of inherited retinal diseases (IRD), based on two of the patient episodes I have seen over the past 30 years in practice.

Part one considers case studies and a wider view of IRD and part two looks more closely at non-optical support that we can offer our patients including discussions around genetic counselling. Anonymised images have been supplied with grateful thanks; names and identities of the characters changed.

Case 1

Daniel came to see me one May during the half-term break for his first eye test with the practice. He had been tested at primary school with the school vision screening service but never been to an optometrist. Aged 16, he was applying for his provisional driving licence and his mum had ‘nagged him’ in to being seen by an optometrist while he was still entitled to an NHS eye examination.

His dream was to become a Royal Navy helicopter pilot and he was about to take his GCSEs. Born in September, he was old for his year and looking forward to being able to pass his driving test by the following Christmas so he could drive himself and his mates to sixth-form college. Typically for many youths of that age, Daniel did not want his mum to join him for his eye examination. He was very independent, bright and chatty.

All seemed well as we began. He was fit and well with no visual symptoms or headaches. He denied any family ocular history other than his paternal gran had just had her cataracts removed and was very excited by her restored sight. Daniel’s main hobbies were cross-country running (he belonged to a local club) and he enjoyed swimming. He was unusual in that he did not spend a lot of time on computer games or his phone and had a strong motivation to do well in his forthcoming exams.

There was nothing untoward about the eye examination until I performed some ancillary testing prior to ophthalmoscopy. Unaided visions were 6/6 R and L, refraction showed a negligible amount of astigmatism. Ishihara test plates were a bit laboured, which I was not expecting, and monocular City test showed a repeatable anomaly in the right eye. As Daniel did not have any known family history of colour deficiency, I decided to consent him that we would speak to his mother to fill in the ‘gaps’ in the history.

Volk 78D BIO examination showed pale fundi with some indistinct mottling in the mid periphery of the right retina and in the left eye there was some clear pigmentation in a clump similar to that found in retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in the upper temporal quadrant. The left foveal reflex was more distinct than the right. Both optic discs were flat and minimally cupped with mildly more pallor perhaps in the right eye.

At this point I had a dilemma. With imminent important public examinations approaching, it seemed unfair to bring Daniel back with his mother for further testing and visual field testing until the exam season was past. His sight was good and he was not concerned. We had a discussion about repeating the colour vision test and adding in some retinal imaging with Optomap and a field test after the exams.

I sent Daniel off unconcerned, pleased that he did not need glasses and he agreed to rebook later in the summer. I made a note on the electronic system to flag up his notes for a two-month recall.

Typically, for a ‘post-exams teen’, it completely slipped Daniel’s mind to return for additional testing and at the end of July, with the diary prompt, I decided to call him to bring him back as we had agreed. I asked him to bring either or both of his parents. He arrived the day of his GCSE results, alone and rather preoccupied and excited by a fantastic set of results.

I asked him to call his mum so that we could chat through the family history. Fortunately, she was in the supermarket nearby and able to ‘pop in’ when she was finished. We repeated the colour vision test with a consistent result and took Optomap images with autofluorescence after we had completed the visual fields test.

Sita 24-2 threshold testing showed some inferior reduction in sensitivity in the right eye and the left eye was entirely normal. FF120 suprathreshold fields showed some more obvious patchy loss in the mid peripheral field in both eyes.

I asked Daniel to wait for his mum and she arrived when I was 15 minutes into my next consultation. By this time, she was irritated with Daniel that he had forgotten to tell her she might be needed and we sat down for a discussion of the results. The family history was helpful as there had been a maternal great aunt of Daniel’s who now lived in Australia who had ‘bad eyes’ but ‘could see when she wanted to’ but couldn’t drive or see in the dark.

This gave me the opportunity to explain that some of the results we had seen during both of Daniel’s appointments and that it was possible that there was a similar condition, which might be genetic that would require an ophthalmological opinion. I was acutely aware of the timings.

Daniel had done brilliantly in his GCSEs and was off to college imminently to study maths, physics and psychology a long 20-mile bus journey from home. He had his provisional driving licence and his first set of driving lessons booked. Diagnosis was going to be very important to the rest of Daniel’s career.

Naturally, he was crushed and most important to him was whether he would be able to drive or not. We agreed to run an Esterman Driver’s field test, which happily he passed with 100% and I wrote to his GP for onward referral for diagnosis.

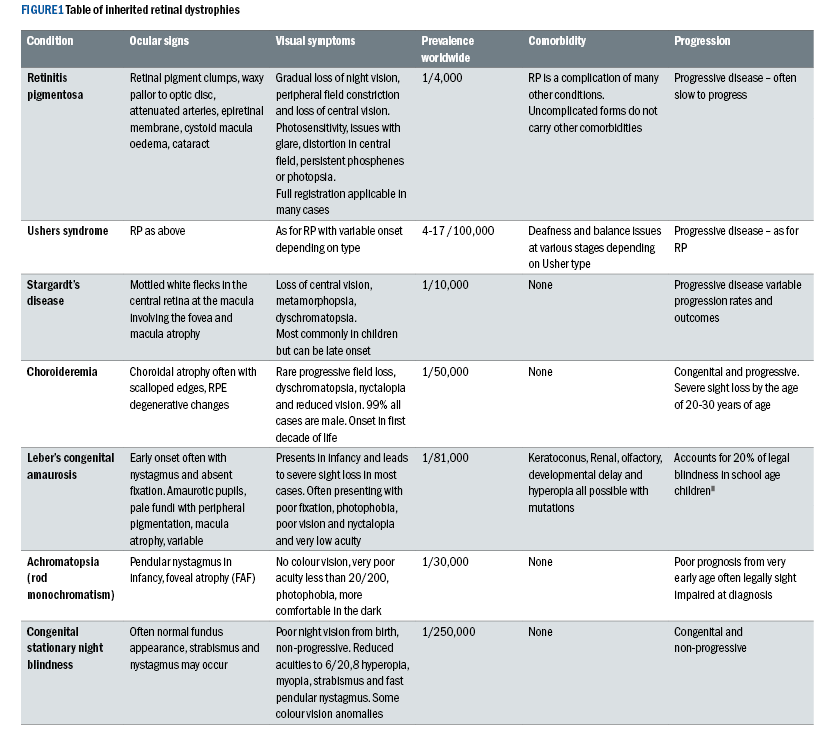

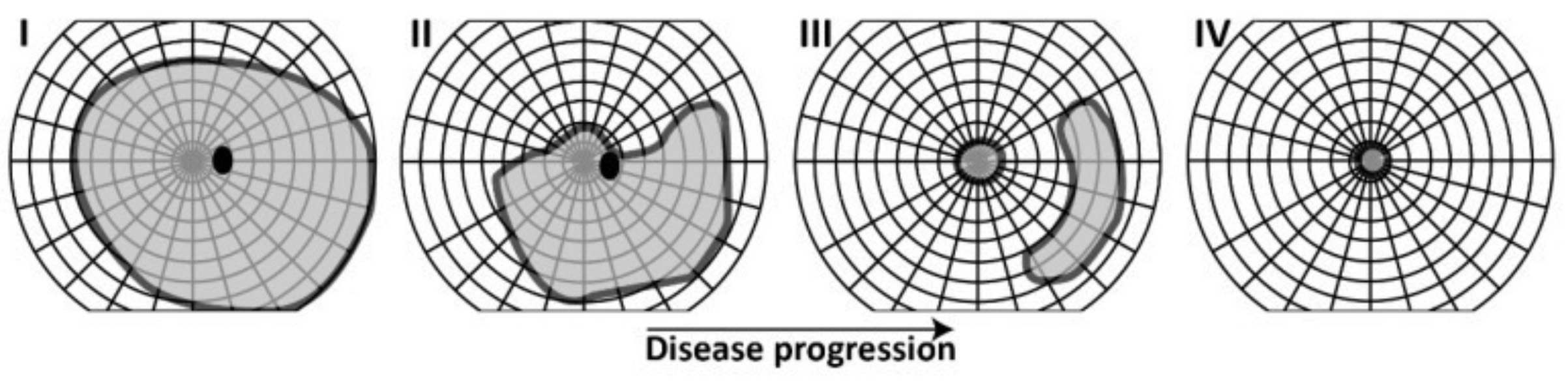

This is not a scenario that is uncommon to all optometrists. Retinitis pigmentosa is the most common type of hereditary retinal dystrophy with a prevalence of 1:4,000 worldwide. Often associated with other syndromic conditions, it is a bilateral

condition that often presents during the teenage years but is sporadic in its severity and speed of progression.

There are three types of genetic inheritance; autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant and X-linked as well as sporadic cases with no clear genetic component.

Most types of RP are characterised by some type of nyctalopia with poor visual performance in mesoscopic and scotopic conditions. Often this is noted by parents of children who go on to be diagnosed with RP, well before they are in their teens.

RP has a number of clinical signs, however, there are three which are most consistent. The condition often begins with pale flecks in the mid-peripheral retina, which later become the hallmark ‘bone-spicule’ pigmented clumps that Franciscus Donders (1857) used in his naming of the disease when it was thought to be inflammatory.

Arterioles become attenuated, further mid-peripheral pigmentation occurs and the optic disc takes on a waxy pallor. Later stages of the clinical presentation include epiretinal membrane, cystoid macula oedema and cataract.

Often, there are high degrees of with the rule astigmatism, corneal ectasia, and an increased risk of developing glaucoma often with very shallow anterior chamber angles. Due to the association with other syndromes, there is enormous variance as detailed below in the accompanying comorbidities which may be seen.

Figure 2: Classic Retinitis Pigmentosa. The author reserves the rights to this image.

Symptoms are slow to be noticed in binocular patients as disease progression is often slow. Classic visual field loss begins in the mid-periphery with islands of reduced sensitivity coalescing. Often this goes unnoticed until sufficient inferior field loss has occurred and the patient begins to become more accident prone ie tripping on steps, A-boards, dogs, small children, bollards, and being poorly spatially aware in the dark.

Night vision is often difficult from an early age and accidental injuries such as falling on stairs or ‘shouldering’ the door frame in the dark being common. As field loss progresses it does not respect the midline in presentation as it might with early glaucomatous loss and often the very far periphery has islands, which are spared longer term.

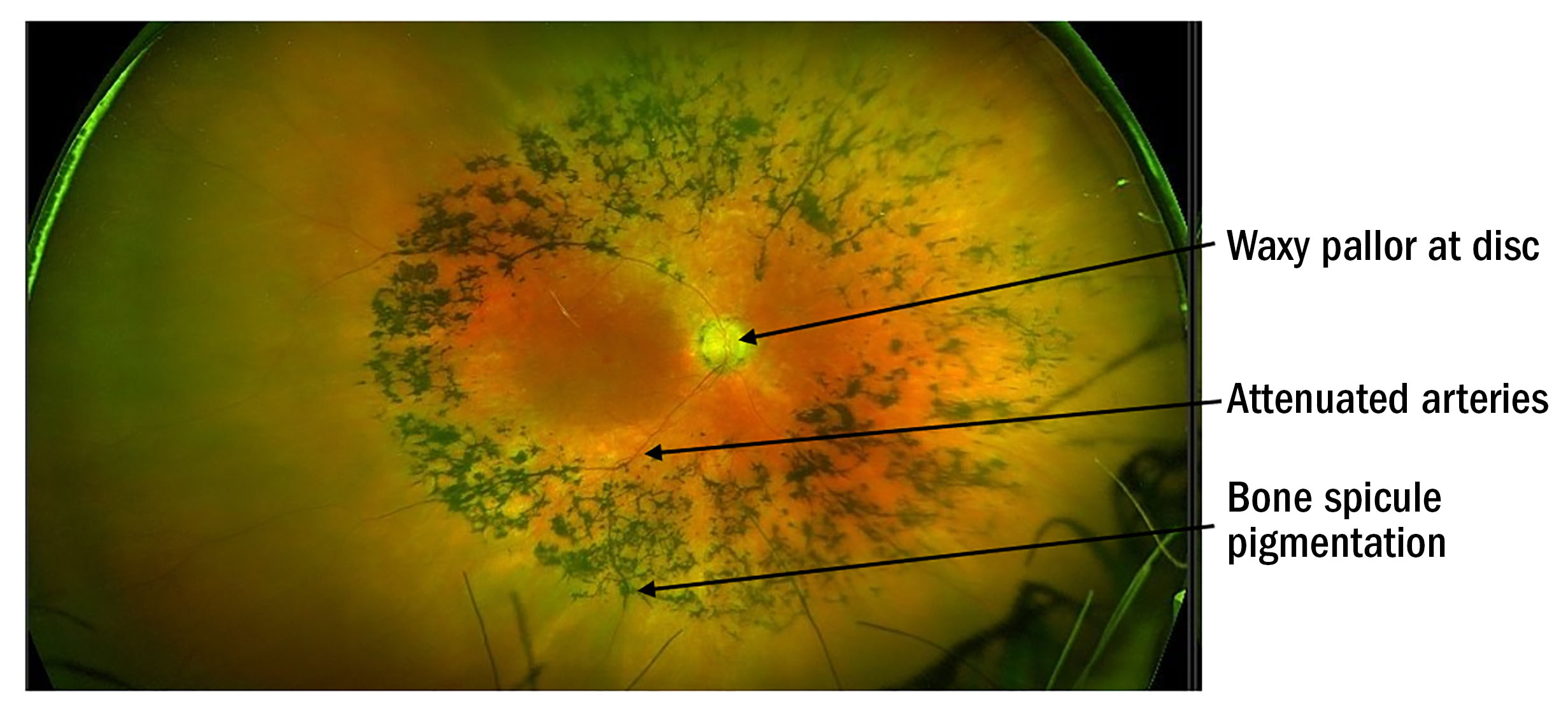

The macula field is the last to be affected with end stage field loss being tubular with less than five degrees of central field remaining (see figure 3). Photosensitivity becomes an issue later in the disease,2 with poor contrast sensitivity worsened by glare. Patients adapt well in the early stages as progression is usually slow.

Figure 3: Progression of Goldman field loss illustration for retinitis pigmentosa1

(Image reproduced with thanks to Nguyen XT, Moekotte L, Plomp AS, Bergen AA, van Genderen MM, Boon CJF. Retinitis Pigmentosa: Current Clinical Management and Emerging Therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Apr 19;24(8):7481. doi: 10.3390/ijms24087481. PMID: 37108642; PMCID: PMC10139437)

Case 2

Robyn was a longstanding patient with me and was diagnosed with Usher syndrome type 2 in their teenage years. Last year, at 45 years old, they had finally had cochlear implants. The deafness was picked up when they were at primary school, however, back in the early 1980s less was known about the importance of early intervention.

As a result, they have relied on lip reading and sign language while in mainstream education, her hearing aids had not been terribly successful and so her cochlear implants were a big step forward. The RP was slow to progress and Robyn has managed to maintain a busy accountancy practice working full time in a small rented office.

Being single with no dependents other than their black cat, Sherlock, Robyn wanted to spend more time with their two adorable eight-year-old twin nieces, also both with Usher syndrome and living with Robyn’s brother in London. Robyn’s biggest issue is that their speech was not tonally great and hearing had been quite poor, so they had been reluctant to engage with technological adaptions to support work, such as ‘Jaws Fusion’ or ‘Dragon’ speech to text software.

Spending increasing time on a screen since the Covid-19 pandemic, both socially and for work, was becoming a problem to them, and Robyn was struggling with symptoms of eye strain. For Robyn, it is hard to get out and about to socialise. Venturing out in the dark, in crowded, noisy places like the pub is their worst nightmare.

Robyn saw me for an update in computer glasses and advice on where to get some rehabilitation support, which they felt they really needed as they were feeling more and more isolated. Surprisingly, Robyn had not ever been sent to see an ECLO (eye clinic liaison officer) after diagnosis of the RP, or been offered certification for visual impairment and this was a conversation I felt that was going to be of huge benefit.

Robyn and I chatted through the process of engaging in some further support via several referral routes. The Sita-Fast 24-2 showed that there was approximately five degrees of field remaining in the central field RE and a little more but less than 10 degrees in the left. Acuities were 6/12 R and L with negligible distance prescription and reading spectacles achieved N8.

Fundus photographs with Optos including fundus autofluorescence were taken and we agreed a referral to the ophthalmology team via the GP would be helpful. We looked at dispensing lenses with a minimal neutral tint for glare and had a conversation about workstation set up with an ancillary screen and touch screen on the laptop.

The College of Optometrists’ handout on lifestyle offers some tips and healthy habits for screen work, which I felt would be appropriate as Robyn already had a lot of information to take in and remember. We discussed how people with significant visual field loss have issues locating the computer mouse and cursor on a screen.

Robyn was keen to be referred for certification so that a disabled railcard could be used and I suggested that I got in touch with the local sensory loss team for a home visit and to discuss white cane training. Robyn was not sure about a cane because it would make them ‘stand out’. Really, they were hoping to be referred for a guide dog.

I explained that this was the next step on that journey and that a ROVI would be able to discuss all the mobility options available. We discussed all the benefits that might be available to them with certification such as Access to Work (for obtaining the right type of tech such as Zoom Text for screen work), as well as tax benefits and being able to apply for PIP (Personal independence payment).

This was a potential lifeline for Robyn who was becoming more and more depressed and feeling trapped by their disease. Having not been ready to accept help until now, Robyn was taking the right steps to keep themselves independent and able to leave the house without fear.

Usher Syndrome

Usher Syndrome is the most common form of hereditary deaf-blindness. It affects between 4-17/100,000 worldwide3 and falls into three main sub-categories. The deafness severity and age of onset is used to define the Usher type and each has differing presentations of progression of sight loss.

Initially described as an autosomal recessive disease, Usher syndrome has a complex genetic variance. The common factor in the loss of sight with the loss of hearing lies in the anomalous protein, which affects the cilia portion of the rod and cone photoreceptors and also the cilia of the ‘hearing’ cells in the inner ear. The contribution of disease in the ear may also affect the vestibular system and lead to balance issues.

Ushers 1 Type 1 is usually diagnosed very early on in childhood with profound hearing loss, which leads to intervention with cochlea implants by the age of two years. It is often picked up in infant screening or by parents who notice their child cannot hear them or does not startle to sudden loud noises.

This patient category tends also to suffer from vestibular issues affecting balance, they may be slow to sit up or not be able to sit unaided and are slow to walk. They can learn to compensate for their poor balance using visual cues but this is slow. Night vision problems occur before the end of the first decade of life, with RP diagnosed pre-puberty.

By 50 years old, 50% of type 1 Usher will be retain visual acuities worse than 6/12 and the deterioration continues with advancing years. Usher type 1 affects between 22-44% of all cases.3

Ushers 2 Type 2 is the most common sub-type affecting over half of all Usher cases. It presents severe hearing loss in early childhood (pre-oral stage) or in infancy. There is an absence of vestibular problems and milestones for sitting and walking are often normal. The RP is usually diagnosed post-puberty and fundus examination may well be normal until later teens.

Diagnosis is usually made via audiology referral to ophthalmology when electrodiagnostic testing in the hospital eye service can detect abnormal ERG well ahead of retinal signs. This with genetic testing supports the Usher type 2 diagnosis. By the age of 50 years old, 75% of type 2 Usher retain 6/12 acuity.

Ushers 3 Type 3 presents with mild hearing difficulties later in childhood and variability of vestibular involvement, which can affect balance in later life. The onset RP occurs post-puberty. It is very rare and accounts for up to 4% of known cases worldwide. Visual acuities of 6/12 are maintained by the age of 50 years old in 75% of cases. There are also other non-typical Usher variations, which are not discussed in this article.

Diagnosis of Usher syndrome involves screening-out other causes of congenital hearing loss in infants suspected of type 1 and 2 Usher. These include congenital cytomegalovirus, rubella, history of sepsis, a history of prematurity and long stay neonatal intensive care at birth. Early screening for genomics, and audiology testing is completed before referral to ophthalmology where electrodiagnostic and VEPs are used to look for specific rod/cone electrical conductivity patterns.

Type 3 disease, although rare, presents later and so may possibly be seen in optometric practice before the audiology team or ophthalmology become involved. Being aware that Usher syndrome can present with normal retinae in these types is important and parents should be encouraged to seek referral if they are concerned about their child’s hearing as early diagnosis is beneficial to all patients regardless of there currently being no treatment for the RP.

Stargardt

Stargardt disease is much lesser known of the retinal dystrophies, affecting the central vision and quite distinct from macula degeneration. Onset is predominantly in childhood with a gradual blurring of the central vision, dyschromatopsia and loss of definition.

Often distortion is reported with patchy central vision, with endpoint disease showing macula atrophy and the patient reporting a central discrete scotoma. Fundus photography with fundus autofluorescence may show areas of retinal pigment epithelium distress and atrophy more clearly than ophthalmoscopy in the early stages.

Cases have been reported in adulthood, however, this is rare, but it is important to bear in mind that it can affect any age. Later onset Stargardt presents occasion with foveal sparing and therefore the visual outcome can be more optimistic.4 The genomics are very variable with a prevalence of 1/100,000 worldwide.

I have two patients with Stargardt disease and have met many more with the disease. Generally, they manage very well with low vision aids and they do not have the same mobility issues as those with peripheral vision loss. If you have a patient with Stargardt and they are asking you about nutritional advice for their eye health, it is important that they know that they should not take additional vitamin A supplements and should look carefully at the amount of vitamin A they consume in their diet.

This has been shown to affect the condition adversely in studies. There will be more about vitamin supplements for retinal health in part two. In part two, I will discuss the outcomes of the two case studies and look at how the optometrist can provide continued care and support post diagnosis.

- Sarah Arnold graduated from City University in 1993. Her work has taken her from sub-Saharan Africa to the Hospital Eye Service, Academia and Independent practices in Devon and for the last 25 years in Hampshire. She is involved in the sight loss sector, presenting training and patient facing content for those living with sight loss and their colleagues and families.

References and Bibliography

- Nguyen XT, Moekotte L, Plomp AS, Bergen AA, van Genderen MM, Boon CJF. Retinitis Pigmentosa: Current Clinical Management and Emerging Therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Apr 19;24(8):7481. doi: 10.3390/ijms24087481. PMID: 37108642; PMCID: PMC10139437. (Access 20/3/24)

- Pennesi ME, Birch DG, Duncan JL, Bennett J, Girach A. CHOROIDEREMIA: Retinal Degeneration With an Unmet Need. Retina. 2019 Nov;39(11):2059-2069. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002553. PMID: 31021898; PMCID: PMC7347087.(Access 20/2/24)

- Toms M, Pagarkar W, Moosajee M. Usher syndrome: clinical features, molecular genetics and advancing therapeutics. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2020 Sep 17;12:2515841420952194. doi: 10.1177/2515841420952194. PMID: 32995707; PMCID: PMC7502997. (Access 20/3/24)

- Tanna P, Strauss RW, Fujinami K, et al, Stargardt disease: clinical features, molecular genetics, animal models and therapeutic options British Journal of Ophthalmology 2017;101:25-30.(Access 21/2/24)

- Sofi, F, Sodi, A, Franco, F, Murro, V, et al, Dietary profile of patients with Stargardt’s disease and Retinitis Pigmentosa: is there a role for a nutritional approach? BMC Ophthalmol 2016, 16, 13. (Access 21/3/24)

- Huang CH, Yang CM, Yang CH, Hou YC, Chen TC. Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis: Current Concepts of Genotype-Phenotype Correlations. Genes (Basel). 2021 Aug 19;12(8):1261. doi: 10.3390/genes12081261. PMID: 34440435; PMCID: PMC8392113. (Access 21/3/24)

- Pang JJ, Alexander J, Lei B, Deng W, Zhang K, Li Q, Chang B, Hauswirth WW. Achromatopsia as a potential candidate for gene therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;664:639-46. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1399-9_73. PMID: 20238068; PMCID: PMC3608407. (Access 21/3/24)

- Zeitz C, Friedburg C, Preising MN, Lorenz B. Überblick über die kongenitale stationäre Nachtblindheit mit überwiegend normalem Fundus [Overview of Congenital Stationary Night Blindness with Predominantly Normal Fundus Appearance]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2018 Mar;235(3):281-289. German. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-123072. Epub 2018 Feb 1. PMID: 29390235. (Access 21/3/24)