While verbal communication lays the foundation for patient-clinician interactions, non-verbal cues, despite their frequent oversight, have a vital role in effective patient care within the healthcare sector. They are equally important in conveying empathy, building rapport and ensuring patient comprehension and satisfaction.1

This is evident across various healthcare disciplines where frameworks such as the Patient-Centered Clinical Interview McWhinney Model and the Calgary-Cambridge Guide are employed, which demonstrate the impact of non-verbal communication.2,3 These models, which are commonly used in medical education in the UK, stress the significance of clear communication, including non-verbal communication, for promoting collaborative doctor-patient relationships and improving patient outcomes.

Adapted for optometry, these models offer valuable insights into enhancing patient-centred care and overall satisfaction. Just as optometrists adhere to professional standards outlined by regulatory bodies such as the General Optical Council, mastering non-verbal communication is important for delivering high-quality optometric services.4 This CPD article provides a comprehensive overview of various non-verbal cues by exploring the types, functions, and their impact on patient-clinician interactions and patient outcomes.

Body language

The language of the body goes a long way. Optometrists communicate not only through words but also through their posture, gestures and facial expressions, which can either complement, reinforce or contradict verbal communication.5 A confident posture can portray competence and assurance, instilling a sense of trust in patients, allowing them to feel safe.

Even the way the consultation room is set up can affect aspects such as arm and leg positions, body orientation and interpersonal distance, which all have an impact on how the patient perceives the optometrist. For example, leaning forward can signal attentiveness and engagement, while leaning backward with arms crossed may suggest disinterest.

Thoughtful gestures can be a good way to reassure patients and show empathy during eye examinations, creating a comfortable atmosphere. These can range from many things, such as offering the patient a seat, offering some tissues in response to emotions or spending more time with patients to illustrate a condition that they are struggling to understand.

Furthermore, maintaining appropriate facial expression and eye contact is just as important; it creates a genuine connection, conveying attentiveness and empathy. Optometry practice staff, particularly front desk personnel, use a simple warm smile to create a welcoming and friendly atmosphere for patients. Studies have shown that smiling not only signals acceptance but also has physiological benefits for both staff and patients, which plays a crucial role in building rapport.6

These are all important factors of ‘active listening’, which extends beyond simply listening, but also includes aspects such as smiling, nodding, leaning forward and maintaining eye contact. Nodding in acknowledgment and mirroring expressions conveys attentiveness, creates a safe and open environment for patients to share their experiences and ask questions.

Through these subtle yet powerful non-verbal cues, optometrists can demonstrate a genuine commitment to understanding their patients’ concerns. These non-verbal signals assure the patient that their optometrist is fully present and invested in providing personalised eye care.

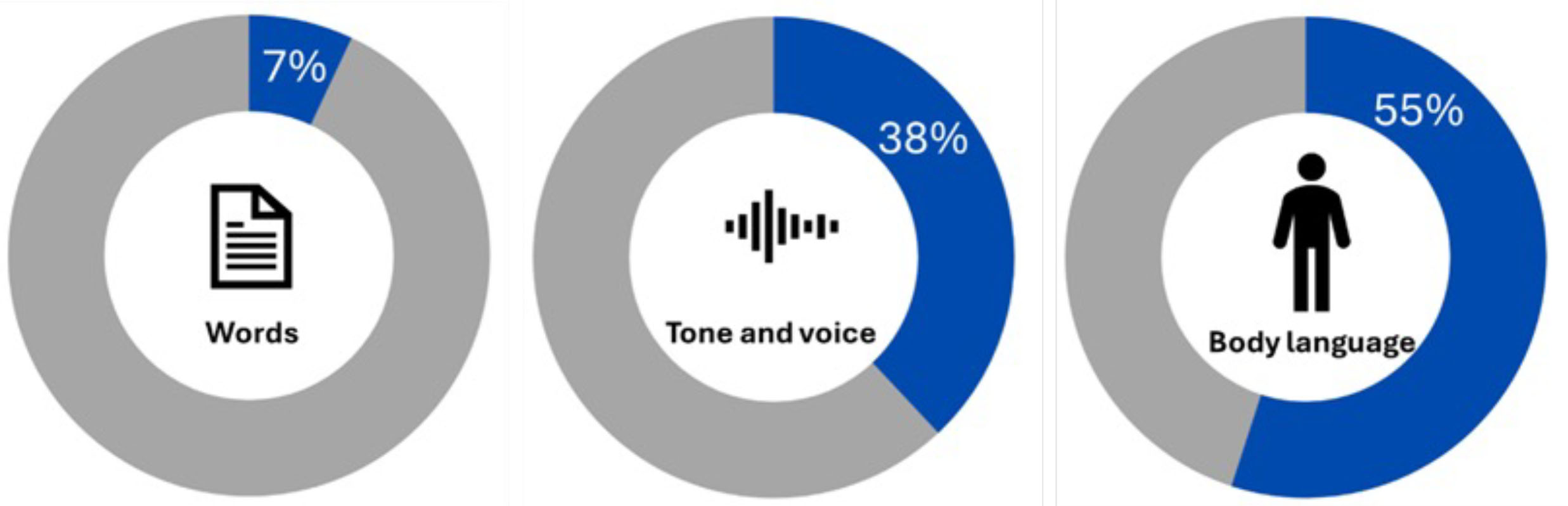

Figure 1: Mehrabian’s model suggests much of the communication around feeling is non-verbal

Not only is using good non-verbal skills important, but optometrists are encouraged to demonstrate sensitivity to patients’ non-verbal cues by being attentive to unspoken signals from the patient that may indicate discomfort or lack of understanding.7 This allows the optometrist to gain a better understanding of the patient, and thus improve patient care.

A study conducted by Wang and colleagues8 highlights the significance of non-verbal communication in the context of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) care. Their findings suggest that optometrists who are sensitive to non-verbal cues, such as facial expressions and body language, are better equipped to gauge patient understanding, knowledge and attitudes related to AMD.8

By incorporating non-verbal communication skills into their practice, optometrists can establish stronger rapport with patients, enhance patient satisfaction, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Proxemics

Proxemics describes the concept of interpersonal distance, ie physical space between individuals during interactions. The strategic use of space is a non-verbal tool that can either enhance or hinder communication and thus influence patient-optometrist interactions and comfort levels.

Optometrists must understand the varying norms and preferences regarding the appropriate personal space and be mindful of adapting the distance between themselves and patients in accordance with cultural norms.5 As Davies highlights, respecting personal boundaries and adapting interpersonal distance according to cultural norms contribute to establishing trust and fostering a positive patient experience during an eye exam.6

By respecting personal boundaries and cultural preferences related to personal space and privacy, optometrists can establish trust and establish a sense of ease, contributing to an overall positive patient experience. This nuanced understanding underscores the significance of cultural competence in creating an inclusive and patient-centred optometric practice.

Touch

The use of touch can be a powerful element of communication where relevant, but it requires a mindful approach. It is important recognise the potential of touch to convey empathy, and thus building rapport and establishing a positive patient experience.5 However, appropriate, and respectful application is the key.

Touch should be employed with sensitivity to individual preferences and cultural considerations, as the same scenario may violate some patients’ cultural or religious beliefs.9 Therefore, understanding how cultural and religious norms influence non-verbal expressions of empathy, like touch, is crucial for developing trusting provider-patient relationships, particularly in cross-cultural clinical encounters.10

Optometry education programs should incorporate training in the interpretation of non-verbal behaviour to enhance empathic cross-cultural communication and reduce implicit biases among healthcare providers.

Vocal cues

Emphasising the content of verbal communication can be achieved through the tone of voice. Vocal cues include factors such as the loudness of the voice, voice pitch, speech rate and tone variations. These cues not only serve to reinforce verbal messages non-verbally but also play a crucial role in expressing emotions, attitudes and intentions during communication.5

For instance, a soothing tone delivered at a moderate pace with pauses can convey patience, empathy or reassurance, creating a sense of comfort and trust. On the other hand, a fast-paced and harsh tone may signal impatience, frustration or anger, potentially leading to misunderstandings or discomfort. The tone of voice significantly influences how patients perceive and interpret interactions with their optometrist during consultations.

Existing studies in optometric care

The importance of non-verbal cues is not new to research. In 1967, psychologist Albert Mehrabian introduced a formula to demonstrate the relative significance of various components in communicating the emotions or attitudes in speech.11 Mehrabian’s model suggests that the majority of meaning regarding feelings and attitudes is conveyed through non-verbal cues rather than verbal expressions.

He measured this by attributing 7% of the meaning to words, 38% to tone and voice, and 55% to body language.11 This principle is commonly referred to as ‘the 7%-38%-55% Rule’. As optometrists, we can take this rule and apply it to clinical practice, by paying attention not only to what is said but also how it is said, and the non-verbal signals being sent to the patients.

Using this rule, optometrists can aim to improve patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment plans and overall outcomes. More recently, Dirk Vom Lehn, Professor of Organisation and Practice, conducted a study to observe how optometrists interact with their patients by watching and analysing video recordings of 62 eye examinations.12

The study found that in addition to verbal communication, non-verbal communication, such as maintaining eye contact at certain key moments and managing the way instruments are brought close to the patient’s eye, was found to help keep patients relaxed and communicative.

The team then collaborated with optometry university departments to create new training material for optometrists. They developed credit-bearing workshops, written material, and an assessed online for continued education for optometrists. This research then influenced the development of university teaching programs.

While existing research highlights the importance of non-verbal communication in healthcare and its effect on patient outcomes,13 further investigation into its precise effects on patient outcomes, such as satisfaction, treatment adherence and diagnostic accuracy specifically in optometric care, is needed.

Understanding the nuances of non-verbal cues in the optometry setting could lead to enhanced patient experiences and improved clinical outcomes.

Training and Education in Non-verbal Communication

Incorporating non-verbal communication training into optometry education programs and continuing professional development, is crucial for equipping optometrists with the skills necessary to provide high-quality patient care.

One effective teaching methodology for non-verbal communication training is simulation exercises with simulated patients.14 These exercises involve simulated patient encounters with actors who are well versed in the patient experience and a patient’s condition, in controlled environments.

This would allow optometry students and practising optometrists to practice and refine their non-verbal communication skills in realistic scenarios. Simulation exercises can encompass a range of patient interactions, from routine eye examinations to sensitive discussions about diagnosis and treatment options.

By providing opportunities for hands-on practice, simulation exercises enable clinicians to develop confidence and competence in using non-verbal communication effectively in the clinical setting. The application of such cues in a more practical setting of the examination room brings together the theory and practice, making these learning points more applicable to daily practice.

Role-playing scenarios are another valuable tool for enhancing optometrists’ competence in non-verbal communication skills. In role-playing exercises, participants take on different roles, such as optometrist and patient, and engage in simulated interactions that mimic real-world clinical encounters. Subsequently, the optometrist can observe how the non-verbal cues can be given as well as taken.

This approach enables participants to explore various communication techniques, receive feedback from peers and teachers and identify areas for improvement. Role-playing scenarios encourage active participation and create a supportive learning environment conducive to skill development. This method of teaching has been adopted by many medical schools and is also transferable to optometry education.

Reflective practice is key to non-verbal communication training in optometry education and professional development.14 Optometrists are encouraged to reflect on their communication experiences and consider how their non-verbal signals may have influenced patient interactions and outcomes. Reflective practice promotes self-awareness and critical thinking, empowering optometrists to perfect their communication skills over time.

Furthermore, mentorship and peer support can play a valuable role in non-verbal communication training.14 Supervising optometrists can serve as mentors, providing guidance, feedback and encouragement to students and trainees. This is something that has been widely incorporated throughout the pre-registration programme and has proven successful in the training for optometrists.

Conclusion

In conclusion, perfecting non-verbal communication is not just a skill but a foundation of effective optometry practice. By recognising its importance in patient-clinician interactions, optometrists can improve the quality of care they provide and create meaningful connections with their patients.

Moving forward, optometrists can enhance their practice by actively incorporating non-verbal communication techniques into their daily interactions. This may involve ongoing training programs and workshops tailored to developing proficiency in reading and responding to non-verbal cues.

Additionally, incorporating awareness and sensitivity to cultural differences in non-verbal communication can further strengthen patient relationships and promote inclusivity within optometric practices. Therefore, the importance of incorporating non-verbal communication training into optometry education programs and continuing professional development initiatives is imperative.

This ability to connect on a non-verbal level is particularly crucial in optometry, where patients may feel vulnerable or anxious about their eye health. Competence in non-verbal communication is a vital skill that allows optometrists to provide patient-centred care that is both empathetic and effective, leading to improved clinical outcomes and overall patient well-being.

- Anneka Ali is a part time optometrist at Evolutio Ophthalmology and is now pursuing a medical degree at St George’s University of London. With a keen interest in medical education, she actively engages in roles such as anatomy demonstrator and clinical and communications skills peer tutor at the university.

Disclosures

The author declares no conflicts of interest related to this article.

References

- Best Practice for Patient-Centered Communication: A Narrative Review. King, Ann and Hoppe, Ruth B. 3, 2013, J Grad Med Educ, Vol. 5, pp. 385-393.

- The Calgary – Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: An aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Kurtz, Suzanne M. Silverman, Jonathan D. 1996, Medical Education, Vols. 30,2, pp. 83–89.

- How clinical communication has become a core part of medical education in the UK. Brown, Jo. s.l.: Medical education, 04 2008, Vol. 42, pp. 271-8.

- Communication in optical practice 1: Importance of communication. I, Davies. s.l.: Optician, 17 January 2020, Vol. 7838, pp. 28-31.

- Cousin, Gaëtan and Mast, Marianne. Non-verbal communication in health settings. Encyclopedia of Health Communication. 2014.

- Communication in optical practice 3: Non-verbal communication. Davies, Ian. 2020, Optician, Vol. 7838, pp. 28-31.

- Clinicians’ accuracy in perceiving patients: its relevance for clinical practice and a narrative review of methods and correlates. Hall, Judith A. 3, Sep 2011, Patient Educ Couns, Vol. 84, pp. 319--324.

- Effective health communication for age-related macular degeneration: An exploratory qualitative study. Wang, E and Kalloniatis, M and Ly, A. 5, s.l.: Wiley Online Library, Sep 2023, Ophthalmic Physiol Opt, Vol. 43, pp. 1278--1293.

- Cultural Religious Competence in Clinical Practice. Swihart, Diana L. and Yarrarapu, Siva Naga S. and Martin, Romaine L. s.l.: StatPearls Publishing, 2024, StatPearls [Internet].

- Culture and non-verbal expressions of empathy in clinical settings: A systematic review. Áine Lorié 1, Diego A Reinero 2, Margot Phillips 1, Linda Zhang 1, Helen Riess 3. 3, Mar 2017, Patient Educ Couns, Vol. 100, pp. 411--424.

- Inference of attitudes from non-verbal communication in two channels. Mehrabian, Albert and Ferris, Susan R. 3, 1967, Journal of Consulting Psychology, Vol. 31, pp. 248--252.

- London, King’s College. Watching for ways to make sight tests better. [Online] Jun 2021. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/spotlight/watching-ways-make-sight-tests-better.

- Association between non-verbal communication during clinical interactions and outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stephen G Henry 1, Andrea Fuhrel-Forbis, Mary A M Rogers, Susan Eggly. 3, Mar 2012, Patient Educ Couns, Vol. 86, pp. 297--315.

- The effect of communication training using standardized patients on non-verbal behaviors in medical students. Park KH, Park SG. 2, Jun 2018, Korean J Med Educ, Vol. 30, pp. 153-159.