Managing patients with a visual impairment is by no means a ‘quick fix’ and many patients require onward referral to specialist low vision services for a more holistic assessment of their needs, practical challenges and impact of sight loss in their everyday life.

In terms of prescribing low vision aids, there is no ‘one fits all’ approach and each patient deserves to be assessed for the best optical or electronic solution for their lifestyle, their level of vision and their everyday needs. Furthermore, low vision practitioners are used to liaising with sight loss charities, other health and social care providers and peer support groups.

This article provides a guide for optometrists and dispensing opticians with the aim to equip them with more confidence in supporting patients with visual impairment attending their practice.

Accessibility

The first thing to consider is the accessibility of the practice website, literature and premises. Websites need to be easy to navigate and easy to read. The use of large, bold print in contrasting colours for essential information is helpful. It would be better still, to allow resizing of text and modification of text and background colours.

High information content and crowded text and images can pose a challenge for people with a visual impairment, while clear headings aid in navigating the website. The same is true for leaflets and other literature to promote services within the practice. Information needs to be concise and in large, bold print with contrasting colours and clear headings.

Within the building, one can support patients with visual impairment through clear signage and wayfinding, obstacle-free navigation, support from markings and handrails and good lighting, especially on stairs and landings. The RNIB provides useful advice and links for further information.1

Creating a welcoming environment and ensuring good communication

To create a welcoming environment, imagine the patient journey from their perspective. A patient who phones the practice to book an appointment may require more time to search for suitable appointment times in their diaries and to write things down. Extra patience is required if their visual impairment is accompanied by hearing impairment as is often the case in the older population.

Once the appointment is made, it can be helpful to confirm the time and date in writing, using double-spaced bold and large print. Confirm that the patient knows how to access the practice and make a note in the diary if there are any special requirements, so that their needs can be met when they arrive.

The Guide Dogs2 charity provides excellent training on how to guide and support people with a visual impairment. During the consultation, it is important that the practitioner faces the patient when they speak, so their voice is projected towards the patient. This enables the patient to compensate for their sight loss through their hearing and when the practitioner is close enough, they can pick up on facial expressions.

It is particularly important for people with sight loss that all instructions are given before the lights are switched off. At the end of the consultation, patients appreciate a clear explanation about their eye health and vision and what can be expected from their optical correction.

The requirements and expectations need to be explained to the patient and to the dispensing optician if the patient is handed over for a dispense. Information should always be available in large, bold print format. This article does not provide a comprehensive guide on how to perform a low vision assessment as this is not what is expected from a routine eye examination.

However, an important question to ask at the end of a routine eye examination is: ‘Is there anything you find difficult because of your eyesight?’ If the patient answers affirmative, the practitioner needs to consider if they can manage the issues within their practice or if onward referral is required to meet the patient’s visual needs and to offer further support.

The College of Optometrists3 states: ‘You should refer the patient if you do not have sufficient expertise to assess a patient with low vision.’ The next section provides some pointers for supporting patients with sight loss attending an optical practice.

Understanding low vision and the benefit of spectacle corrections

The Low Vision Services Consensus Group4 defines Low Vision as follows:

“A person with low vision is one who has an impairment of visual function for whom full remediation is not possible by conventional spectacles, contact lenses or medical intervention and which causes restriction in that person’s everyday life.”

Appropriate spectacle correction is important for all patients, including those with visual impairment. In the early stages of sight loss patients often like to believe that a stronger pair of spectacles will restore their vision. However, eye care professionals (ECPs) understand that while glasses do correct refractive error, they do not compensate for sight loss due to eye or brain pathology.

Therefore, in some cases, stronger glasses are unlikely to help the patient’s eyesight and the patient risks spending money on products they are unlikely to benefit from. It is important that this is explained to patients for them to make an informed decision. Managing expectations, being transparent about their diagnosis and about what can be achieved with spectacle correction supports patients in their decision-making and their perception of the service they received.5

Once a patient understands that their sight loss cannot be fully restored with spectacle correction, they will be more ready to accept other solutions. Depending on each individual case, some patients with early sight loss can be managed within the optical practice. For example, some patients with early sight loss may benefit from a good task light and a high reading addition.

This brings the text in focus at a closer working distance, also known as relative distance magnification. When this is prescribed, it is important to demonstrate the shorter working distance required to bring their close work in focus and to assess if the patient tolerates this form of magnification.

Base-in prisms need to be considered in additions higher than +4.00 and up to +12.00 dioptres, after which binocularity is not achievable. Prescribing high addition reading glasses and other forms of magnification is more effective when this is done in the context of a more holistic low vision assessment. Some important elements of such an assessment will now be considered.

History taking

Patients with a visual impairment experience a range of difficulties in their daily life. Common difficulties include problems with reading and writing, face recognition, watching television and doing tasks for which fine detail is required. Vision impairment affects access to information, mobility, social interactions and emotional wellbeing.

The low vision practitioner seeks to understand the patient’s living situation, their support network, their everyday needs, their risks and how these are related to their visual impairment. With this information, and the information from clinical investigations, the practitioner and the patient discuss what goals may be achievable.

One has to bear in mind that many patients with visual impairment experience negative emotions, which can in turn affect their readiness for rehabilitation. Therefore, emotional wellbeing needs to be addressed in a supportive way.

Assessing visual functions

Distance visual acuity

A standard Snellen chart has very few large letters for people with low acuity. Therefore, a LogMAR chart is the preferred method for acuity testing. It results in a more precise measurement for low acuity and it provides a more positive experience as patients are able to read more letters during the assessment.

Reading acuity

For reading, the Bailey-Lovie word reading chart is commonly used in a low vision setting. This chart contains unrelated words, starting with N80 and gradually decreasing in size.

The reading acuity is a useful tool in predicting required magnification. It is also useful to have a selection of reading samples, such as newspapers and magazines in the practice in order to assess reading ability in a real life setting.

Contrast sensitivity

Reduced contrast sensitivity impacts reading fluency, face recognition and navigation and is an important predictor for quality of life.6-7 Depending on the level of contrast sensitivity, patients may require additional lighting, contrast enhancement or sight substitution.

Different tests are used for contrast sensitivity, such as the Pelli-Robson test or the Mars chart. Demonstrating the effect of low contrast can be a useful tool in explaining the difficulties patients are experiencing.

Visual fields

Amsler grid and confrontation fields provide useful insight into a person’s functional fields. Many patients with macular conditions experience central vision loss and the Amsler grid can provide information about preferred retinal locus for eccentric viewing.

Confrontation fields provide more information about the peripheral fields. Based on the visual fields, advice can be given about visual search strategies, reading strategies and mobility.

Predicting magnification for reading

Firstly, one needs to consider what the patient is currently seeing (threshold print size), what they want to see (target print size) and if this is a spot-reading task or a sustained reading task. For spot-reading tasks it may be sufficient to magnify the print to the level that they can just make out.

Examples of spot-reading tasks are looking up cooking instructions or checking pricing on packages. For sustained reading, such as reading the newspaper, a larger print size is required. As a rule of thumb, the target text needs to be two to three times larger print than the patient’s threshold print size for fluent reading.

This is referred to as the ‘acuity reserve’.8 While this rule of thumb works for many patients, Latham et al9 recommend assessing a patient’s ‘comfortable print size’ to estimate the required magnification level. This can be obtained by asking the patient what is the smallest print size they can read comfortably.

Example 1

A patient finds N16 to be comfortable and they want to read the newspaper (N8). In this case, a 2x magnifier is an appropriate starting point. If the patient also has reduced contrast sensitivity, they may still not be able to see the newspaper despite the appropriate magnification and they may require an illuminated magnifier or a good task light.

Example 2

A patient indicates that their comfortable print size is N48 and that they want to read the newspaper (N8). This would require a magnification of 6x. Here, we need to consider that reading speed slows down significantly with higher magnification requirements due to the reduced field of view whereby the patient can only see a few letters at a time.

The field of view can be increased by holding the magnifier lens closer to the eye. The practitioner would need to have a discussion about realistic expectations before prescribing a higher-powered low vision aid.

Patients with lower acuities are also likely to have reduced contrast sensitivity. Electronic aids could be a suitable option as they can provide contrast enhancement and are available in different screen sizes.

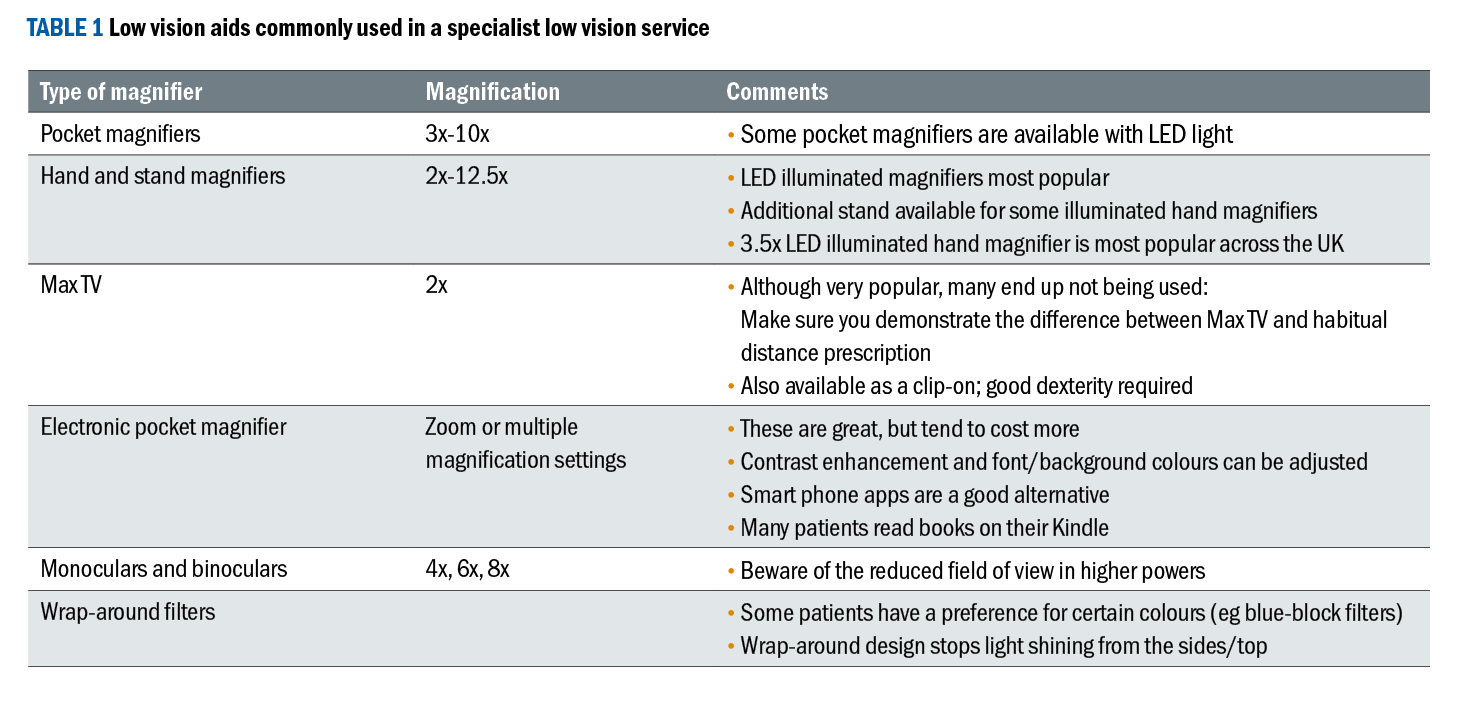

Prescribing appropriate magnifiers requires the practitioner to be familiar with a wide range of magnifiers and a solid understanding of the advantages and disadvantages of specific magnifiers. Table 1 provides an overview of low vision aids that are frequently used in low vision services, but is by no means an exhaustive list.

Sight substitution and strategies

Common strategies for people with a visual impairment are optimising contrast and lighting, and reducing clutter. The home environment can be adapted to facilitate visual search and navigation. Visual search, scanning and reading strategies can be taught. The use of tactile stickers and kitchen aids can improve independence and safety in the kitchen.

Many strategies are case-specific and therefore, patients benefit from a thorough understanding of the underlying reasons for their difficulties in order to empower them with tools to develop their own strategies.

For example, once a patient understands that they have a lower field impairment, they understand that they cannot see the ground ahead of them and may benefit from a stick for tactile guidance.

The same patient may benefit from storing important items in a high cupboard, rather than a low cupboard and from using a reading slope for reading and using a stool for their feet when doing up their laces.

Another patient may have trouble in low contrast and therefore, strategies are aimed at increasing contrast; for example, marking door frames and stairs, improving lighting on stairs and landings, using high contrast chopping boards, crockery and table mats, using thick pens and paper with thicker lines, avoiding patterned tablecloths and furnishings and making sure that their conversation partner does not have a light source behind them.

In both examples, the patient is at risk of falling and therefore, onward referral for mobility training is indicated.

Vision and driving

If a patient does not meet the visual standards for driving, the optometrist has a duty to discuss this with the patient, to advise them to stop driving and to contact the DVLA. Alternative transport options can be discussed with the patient.

The author has come across patients on the register for sight impairment who had never been told they should give up driving, so we should never assume that patients are already informed.

Visual hallucinations

Visual hallucinations, also known as Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS) are common among people with sight loss. Although more and more people with sight loss are familiar with CBS, some patients experience hallucinations and are concerned about their experiences. They are often relieved when the ECP explains this phenomenon and reassurance is often all that is required. The RNIB, Macular Society and Esme’s Umbrella provide further information about CBS and tips about managing the symptoms.

Emotional impact

The emotional impact of sight loss should not be underestimated and screening for depression is becoming a standard aspect of a low vision assessment. When low mood or loneliness are experienced by the patient, signposting to support groups and sight loss charities as well as a referral to the GP for management of these symptoms are recommended.

Certification and registration

Certification for sight impairment or severe sight impairment is the responsibility of the consultant ophthalmologist in most parts of the UK. This is different in Wales, where accredited optometrists within the Low Vision Service Wales have authority to certify patients under specified conditions.

ECPs who provide services for patients with a visual impairment need to be familiar with the benefits, criteria and process of certification and registration in their local area, in order for patients to receive appropriate support at the right time. However, it is not necessary for patients to be registered before they can access services from sight loss charities.

Signposting and getting to know your local support groups

While it is essential for low vision practitioners to have a comprehensive directory of services and a network of professionals who support patients with sight loss in their local community, this is not realistic for all optometrists.

It may be more realistic to have a couple of key contacts, such as the local eye clinic liaison officer (ECLO) or equivalent, local peer support groups and the nearest provider of low vision assessments and low vision aids.

Concluding thoughts

A guide for optometrists and dispensing opticians about supporting patients with low vision would be incomplete without the advice from the experts in the field: our patients. The author attended a local peer group meeting from the Macular Society and asked the group members what was most important to them in terms of the support that optical practices could offer.

They agreed that accessibility was very important and emphasised the need for bold, large, good contrasting print with bite-size pieces of information. They were disappointed that optical professionals (including the hospital eye service) provide appointment letters and other information in tiny print, which is inaccessible for the target group.

They also agreed that a practice should consider accessibility of the premises, as well as communication and guidance throughout a patient’s visit. When they were asked what they valued the most, they all agreed that signposting to sight loss charities, low vision services and local support groups were the most important things an optical practice could do to support patients with sight loss.

- Cirta Tooth works as a specialist low vision optometrist in the hospital eye service as well as in private practice and has just completed a Master’s in clinical optometry at Cardiff University. She enjoys supporting adults and children with visual impairment through teaching, research, raising awareness and involvement in the local community. For information about online or in-person workshops for practice teams, contact Cirta Tooth via her LinkedIn page.

References

- RNIB. Creating accessible information and communication resources for health and social care. Available at: https://www.rnib.org.uk/living-with-sight-loss/independent-living/accessible-nhs-and-social-care-information/creating-accessible-information-and-communication-resources-for-health-and-social-care/ [Accessed 4 March 2024].

- The Guide Dog for the Blind Association. 2024. Sighted Guide Training. Available at: https://www.guidedogs.org.uk/how-you-can-help/sighted-guide-training/ [Accessed 1 March 2024].

- The College of Optometrists. Knowledge, skills and performance: Assessing and managing patients with low vision. Available at: https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/guidance/knowledge,-skills-and-performance/assessing-and-managing-patients-with-low-vision [Accessed 4 March 2024].

- Low Vision Services Consensus Group. A framework for low vision services in the United Kingdom. 1999. London: Royal National Institute for the Blind

- Berger, ZD et al. Patient centred diagnosis: Sharing diagnostic decisions with patients in clinical practice. British Medical Journal. 2017;359. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4218.

- Havstam Johansson L, Skiljic D, Falk Erhag H et al. (2020). Vision-related quality of life and visual function in a 70-year-old Swedish population. Acta Ophthalmologica 98(5), pp.521-529.

- Roh M, Selivanova A, Shin HJ et al. (2018). Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity are two important factors affecting vision-related quality of life in advanced age-related macular degeneration. Pols One 13(5). Article Number e196-481.

- Whittaker SG, Lovie-Kitchen J. Visual requirements for reading. Optometry and Vision Science. 1993;70(1):54– 65. doi:10.1097/00006324-199301000-00010.

- Latham, K, Subhi, H and Shaw, E. Further validation of comfortable print size as a parameter for clinical low-vision assessment. Translational Vision Science and Technology. 2023;12(6): 18. doi:10.1167/tvst.12.6.18.