The decision to give up driving is a major life decision. Many older members of the community are lifelong drivers, with strong preference for private motor vehicle transport. Driving provides the independence to get to essential services and engage with friends and family.

While driving has many benefits, these benefits must be balanced against the risk of injuries on the road. This is particularly important in the UK, as like many high-income countries there is an ageing driving population. In the 12 months leading up to February 2023, there was a four percent increase in the number of people aged 70 years and older with a full licence in the UK.1

The number of drivers aged 70+ years has increased by 53% compared to the previous decade. A 2022 report on road casualties released by the UK government found road fatality rates to decrease for all age groups from 2012 to 2022 except for those aged 50-59 and 70+ years.2

“The number of drivers aged 70+ years has increased by 53% compared to the previous decade.”

The United National has set two Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs: 3.6 and 11.2), which include a commitment to make the roads safer for all road users and have endorsed the Safe System approach to help countries create safer road systems. This is particularly important for safety of older drivers who have an increased risk of crash involvement and are more vulnerable to serious injuries, due to fragility associated with ageing.3,4

Research has shown that older drivers are more likely to be involved in crashes at intersections than their younger counterparts.5 Driving is a complex task, where information is integrated from a dynamic environment and rapid reactions required for safe movement through the road network. It is likely that many older patients presenting to optometrists in the UK are licensed drivers who may also be encountering age-related changes to their vision.

In the UK, there is no set age when a person must legally stop driving. However, when you reach 70 years of age you need to renew your licence if you wish to continue driving. You then need to renew it every three years afterwards. There is legislation that sets the medical standards for driving that every driver must meet, including minimum eyesight requirements for drivers.

These state that you must have an adequate field of vision and a visual acuity of at least 6/12. These requirements are similar to regulations in other jurisdictions around the world. However, the link between evidence and policy in this field is uncertain. The 2021 Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: vision beyond 2020, looked beyond vision to see how vision loss can have impacts on everyday activities, including driving.6

As part of the commission, two systematic reviews were conducted to investigate the impact of vision on driving and are summarised here. The first review investigated the impact of vision on crash involvement, an important measure of safety.7 In recognition that people who have changes to their vision may also stop driving, this review looked for evidence of associations between vision loss and driving cessation.

The rationale for including these two outcomes is that these outcomes are effectively competing risks, a person with vision impairment or diagnosis of a specific eye diseases may give up driving and therefore mitigate their risk of crash involvement. The second review summarised the impact of vision impairment on driving performance.8 Studies were included where driving was assessed on the road or on test courses but excluded studies that used driving simulators.

Overview of studies included in both reviews

Both reviews included a total of 128 studies; 63 were focused on crash involvement, 34 were on driving cessation, four focused on both crash involvement and driving cessation, and 27 looked at driving performance and on-road driving errors. The first review looking at crash involvement and driving cessation included 778,052 participants, while the second review on driving performance included 6,358 participants.

While we included studies of all age groups, 78 of these studies only looked at older drivers. Most of the evidence (85 studies) were from high income countries, like the UK. Most studies were observational (cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control) with only three randomised controlled trials. The majority of the studies were categorised as low to medium risk of bias with most of the studies rated as having high risk coming from low-middle income countries.

Crash involvement and vision

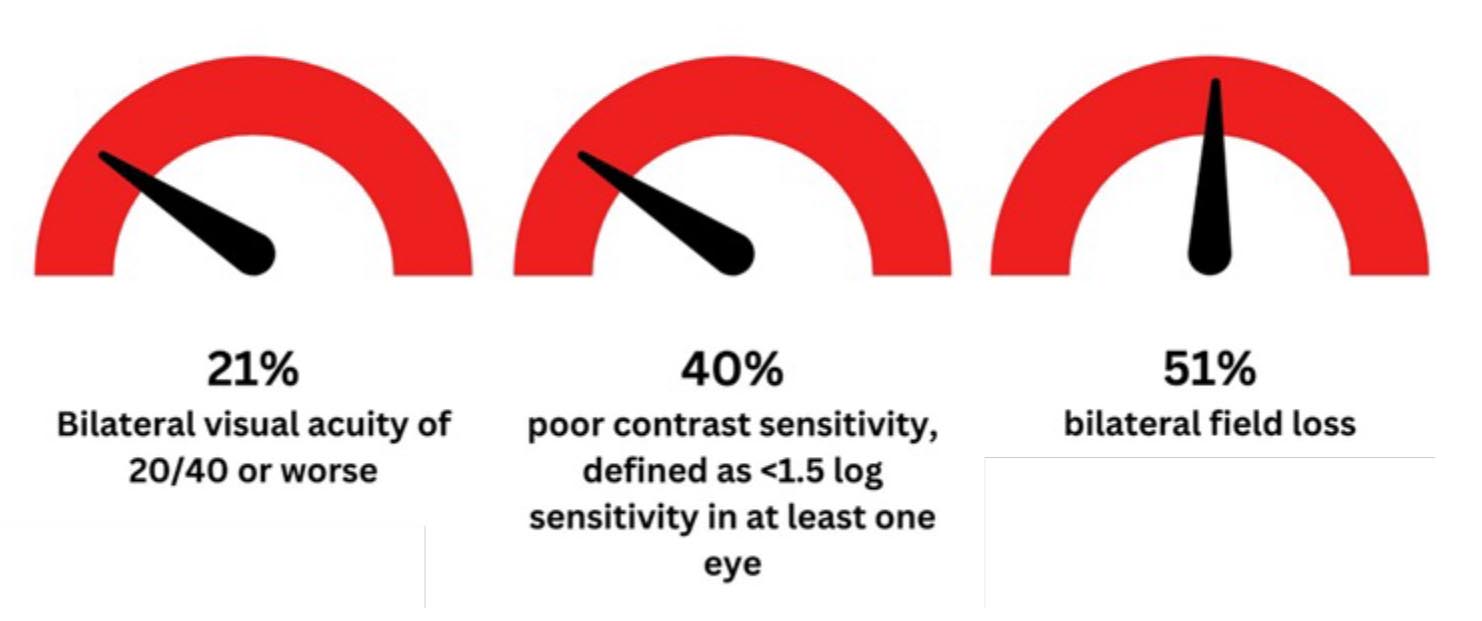

Crash involvement was associated with a several measures of vision. Firstly, drivers with a bilateral visual acuity of 20/40 or worse were found to have a 21% increase in crash risk compared to those with better visual acuity. Secondly, individuals with poor contrast sensitivity, defined as <1.5 log sensitivity in at least one eye, were found to have a 40% increase in crash risk compared to those with normal contrast sensitivity.

And finally, drivers with bilateral field loss were shown to have a 51% increase in crash risk than those without any visual field loss (see figure 1).

Results concerning specific eye diseases, however, were more inconclusive. Despite being one of the most common causes of blindness worldwide, associations between crash involvement and glaucoma were mixed with many studies reporting insignificant increases in crash risk. What was clear, however, was that drivers with more severe glaucoma were consistently found to have higher risks of crashing than those who either did not have glaucoma or had a milder form of the eye disease.

Similarly, associations between increasing crash risk and cataract and AMD were also not found. This suggests that people diagnosed with these eye conditions should have further testing to measure if there is an impact on their vision. Consistent with the results above about poorer vision and worse contrast sensitivity, first-eye cataract surgery was found to halve the risk of crashing. One study went the extra mile and found the risk of crashing post-surgery to be lower in males than female patients.

“First-eye cataract surgery was found to halve the risk of crashing.”

Driving cessation and vision

Poor contrast sensitivity was once again found to be associated with another driving outcome, this time driving cessation. Drivers with poor contrast sensitivity, also defined as <1.5 log sensitivity in at least one eye, had a 30% increased risk of driving cessation than drivers with no impairments to their contrast sensitivity. Glaucoma was found to have an impact on driving cessation, which was related to the severity of disease.

Those with mild glaucoma had a 30% increased risk of driving cessation but those with severe glaucoma were four times more likely to stop driving. Overall, any form of glaucoma increases the risk of driving retirement by 63%. Drivers with cataract were also found to have a 50% increased risk of driving cessation compared to a driver without cataract.

Pooling together studies investigating AMD found drivers with this condition to be 2.2 times more likely than those without macular degeneration to give-up driving. Thankfully though, anti-VEGF injections can prolong driving in affected persons suffering with age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

“...anti-VEGF injections can prolong driving in affected persons suffering with AMD.”

Driving Performance and vision

Poor driving performance measured through a variety of on-road driving measures and errors were linked to declines in visual acuity, contrast and glare sensitivity, and visual field. Impairments in visual acuity led to increased overall errors and poorer scores in on-road driving tests, errors in braking, gap judgement, blind-spot checking, vehicle manoeuvring, indicator use, observations and approach of different driving situations, and mirror checking.

Poor contrast sensitivity resulted in errors in speed control and vehicle manoeuvring while drivers with glare sensitivity struggled with lane changing, speed control and gap judgements. Visual field loss in either eye was associated with poor speed control, restricted or incorrect head and shoulder movements, poor judgements at traffic lights, greater difficulty with turning left when the driver side is on the left, and failure to obey stop signs.

Drivers with severe AMD, causing significant central vision loss, have trouble controlling their speeds and judging the gap they leave from their vehicle to the vehicle in front. These individuals are also less observant while driving and make more errors during traffic light intersections, therefore resulting in poorer overall safety ratings in a driving test compared to someone with either no AMD or mild AMD.

Drivers with more severe glaucoma make more errors dealing with hazard perception and avoidance, observation and approach, and traffic light and give-way intersections than those without glaucoma. These errors may be attributed to the impaired peripheral vision caused by severe glaucoma, which makes it more difficult for the individual to see objects approaching from the sides.

Even though cataracts were not found to worsen driving performance, cataract surgery were found to allow drivers to recognise signs better and make fewer mistakes when recognising and avoiding hazards. Toric corrective lenses can also decrease errors behind the wheel and improve driving performance on on-road tests.

Significance of Results to Eye Health Professionals

These systematic reviews found that poor vision had a measurable impact of driver safety, providing an evidence base for the inclusion of eyesight requirements for licensing. Based on this evidence synthesis, the Lancet Commission for Global Eye Health called for ready access to eye care services for drivers and evidence-based legislation to mitigate the risks associated with vision impairment and driving.

Further, it was stated that with the increasing reliance on motor vehicle transport, maintaining vision is essential for drivers to prevent road traffic injuries and promote independent mobility. The majority of studies in both reviews were focused on older drivers. This makes sense as older adults have higher prevalence of vision impairments and eye diseases.3

Common age-related conditions such as AMD and glaucoma were shown to increase the risk of crashing and was also associated with poor driving performance and driving errors. As a diagnosis of one of these conditions does not necessarily mean that vision is severely impacted. This was supported by the review findings that it was severe glaucoma or AMD that had the greatest impact on safety.

Studies reporting on the milder forms of these eye diseases normally found no associations. Deficits in vision such as reduced visual acuity and visual field loss were consistently shown to impact crashing, driving performance, and driving cessation, revealing the key aspects of vision in glaucoma and AMD that negatively impact driving and decrease safety.

Regular eye examinations, timely access to treatment and active monitoring of progressive eye diseases are therefore critical for maintaining eye health and optimising vision for safe driving.

Ensuring access to the most appropriate eye care services and treatment will also help people to continue safely driving. Fortunately, in the UK, you are entitled to a free eye test if you are 60 years of over, helping to increase access to eye care.

Both reviews have highlighted how important effective cataract surgery coverage is to maintaining driving performance and reducing the risk of crashing.

Efforts to make the cataract surgery pathway clearer to patients are imperative to helping patients ensure their vision is optimised. Effective refractive error correction, including astigmatic correction was also shown to help drivers better see road hazards and signage. As refractive error can impact individuals of all ages it is important that younger drivers are encouraged to regularly test their vision so that any declines can be picked up quickly and monitored.

The conclusions drawn from both reviews therefore support the 74th World Health Assembly resolution (2021) to increase global refractive error coverage by 40% and cataract surgery coverage by 30% by 2030.7 While there is personal responsibility to ensure that you meet medical standards for driving, eye care and other healthcare professionals play a critical role in promoting road safety.

An optometrist can have an active role, discussing driving with patients and informing patients if they have eye conditions or changes to their vision that can impact driving. Giving up driving is a difficult conversation, and clinicians need to be mindful of the need for support during this transition. It has been shown that driving cessation can lead to poorer physical and mental health outcomes in community-dwelling older drivers.

This is why eye care professionals must ensure they do not only tell older drivers they can longer drive but also be able to direct them to resources that help them navigate life post driving, including advice on alternative transport options. Even though such conversations are emotionally difficult to navigate, an evidence-base is available to inform recommendations on driving participation that support safe mobility.

- Dr Helen Nguyen is currently a research fellow based at the George Institute for Global Health. She obtained her PhD from UNSW in 2023 for her thesis, which focused on better understanding safe transport and mobility for older drivers in Australia through the Safe System approach. Dr Nguyen previously worked as a research assistant within the Injury Division for the George Institute for Global Health and then in a similar role at UNSW’s School of Optometry and Vision Science (SOVS).

- Professor Lisa Keay is head of the School of Optometry and Vision Science at UNSW in Australia, she is also an Honorary Professorial Fellow at the George Institute for Global Health. Prof Keay’s research aims to understand two major causes of injury to older people: falls and road traffic injuries. In addition to her academic role, Prof Keay has acted in formal advisory roles to government agencies.

References

- Rathbone M. Surge in senior drivers: UK sees record number of drivers over 70 [Internet]. Driving Instructors Association. 2023. Available from: https://www.driving.org/surge-in-senior-drivers-uk-sees-record-number-of-drivers-over-70/

- Reported road casualties Great Britain, annual report: 2022 [Internet]. GOV.UK. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/reported-road-casualties-great-britain-annual-report-2022/reported-road-casualties-great-britain-annual-report-2022#:~:text=In%20reported%20road%20collisions%20in

- Owsley C, Ball K, Sloane ME, Roenker DL, Bruni JR. Visual/cognitive correlates of vehicle accidents in older drivers. Psychology and aging. 1991 Sep;6(3):403.

- Koppel S, Bohensky M, Langford J, Taranto D. Older drivers, crashes and injuries. Traffic injury prevention. 2011 Oct 1;12(5):459-67.

- McGwin Jr G, Brown DB. Characteristics of traffic crashes among young, middle-aged, and older drivers. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 1999 May 1;31(3):181-98.

- Burton MJ, Ramke J, Marques AP, Bourne RR, Congdon N, Jones I, Tong BA, Arunga S, Bachani D, Bascaran C, Bastawrous A. The lancet global health commission on global eye health: vision beyond 2020. The Lancet Global Health. 2021 Apr 1;9(4):e489-551.

- Nguyen H, Di Tanna GL, Coxon K, Brown J, Ren K, Ramke J, Burton MJ, Gordon I, Zhang JH, Furtado J, Mdala S. Associations between vision impairment and vision-related interventions on crash risk and driving cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2023 Aug 1;13(8):e065210.

- Nguyen H, Di Tanna GL, Coxon K, Brown J, Ren K, Ramke J, Burton MJ, Gordon I, Zhang JH, Furtado JM, Mdala S. Associations between vision impairment and driving performance and the effectiveness of vision-related interventions: a systematic review. Transportation research interdisciplinary perspectives. 2023 Jan 1;17:100753.

- Crofts-Lawrence J, Aindow H. World Health Assembly: New targets for a new decade on eye health [Internet]: The International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness. 2021. [cited 2023]. Available from: https://www.iapb.org/blog/world-health-assembly-new-targets-for-a-new-decade-on-eye-health/.