Every person is unique, and so are their communication needs. For optical professionals, effective communication should be at the centre of all patient interactions, thus ensuring every patient receives a high and equitable standard of eye care. This article will explore some of the barriers faced by children and adults with complex needs in eye care services and discuss different communication methods and reasonable adjustments which could be implemented in optical practice to make eye care more accessible for this cohort of patients.

According to Public Health England,1 learning disability (LD) can be defined as ‘a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn new skills’, which can impact on the person’s ability to cope with everyday life independently. It is estimated that in 2015 in England there were 1,087,100 people with LD, including 930,400 adults.1 It is likely to be apparent if a person has a severe LD; however, people with mild or moderate LD are less likely to have someone supporting them when attending optical practice.

Therefore, eye care professionals need to be able to recognise the potential signs that a patient may have LD, for example, if they are struggling with explaining symptoms and health problems, completing the forms, understanding new information, remembering their date of birth or address, managing money or telling time.

If a patient displays one or more of these difficulties a member of staff should consider having a conversation with the patient about their communication needs. The appropriate support can then be offered to help them understand and retain information relating to their visit.1 It is irrelevant if someone has a LD how severe their disability may be or whether they can read, use a computer or drive, all people have the same right to wear glasses and to have good vision.

SeeAbility2 highlight that vision ‘is about being able to understand the world around you, moving around safely and communicating with other people’. Children have an additional reason for wearing spectacles, as the period for normal visual development is up to around seven years of age, although it is accepted that some visual improvement can be achieved beyond this age.3 To ensure the best possible visual outcome for the child in the future it is crucial that any visual defect is corrected during this developmental period.

Adults with LD are ten times more likely to have a serious sight problem compared to other adults, this risk increases to 28 times for children with LD.4 However, it may not be always possible to know if someone has a sight problem as there may be no obvious signs of poor eye health or even sight loss. Given that problems with vision are so common in people with LD, it is advisable to assume that someone has a sight problem unless it is confirmed that they do not.

In a study from an opt-in eye examination service in English special schools, 438 out of 923 pupils (47.5%) had a visual deficiency, and five pupils (1.3%) had vision too low to be measured.5 Concerningly, hemianopia was found in 13 cases, with five being previously undiagnosed.

So, what constitutes health inequalities in access to eye care for people with LD and/or autism? Some of the barriers exist at both national and regional levels and are generally associated with poor uptake of primary eye care services, lack of signposting, concerns about cost of care and poorly adapted clinical environment. Collecting adequate health history and accurately identifying eye problems can be challenging due to problems with communication and lack of specialist training and assessment skills. People with LD may have difficulties communicating their symptoms, which can often lead to them being overlooked or attributed to the person’s characteristics.6

Overcoming Communication Barriers

Noise can be one of the key barriers to effective communication which is any interference that happens between the communicators. It can appear in different forms, distractions due to pictures on the wall or objects in the room, a noisy toy, interruptions by other people, a ringing phone, external noise of road traffic or people having a conversation.7

A simple solution to overcome such barriers is to reduce background noise by finding a quiet place away from the shop floor, so that everyone involved in the conversation can concentrate on what is being discussed. At the same time, noise can be a welcome distraction; for example, playing a child’s favourite programme on an electronic device can encourage them to focus long enough for the optometrist to complete objective refraction.

Physical distractions are the physical things that can get in the way of the communication process. A typical example can be the environment, for example the testing room may be too hot or too cold or a chair can be uncomfortable. Sensory rooms can be a perfect place to carry out eye examinations in a special school environment; however, certain objects, such as mirrors, can provide too much stimulus and cause unwanted distractions. However, from the author’s experience of working in special schools, it is beneficial to have a range of objects or toys available in order to attract and keep the attention of young patients (figure 1).

Figure 1: Toys and objects to maintain a child’s attention

Autism

While it is not clear what causes autism, it is not an illness and autistic people can live a full life. There are more than one in 100 people in the UK on the autism spectrum.20 Although autism is different for everyone, some of the common characteristics include:21

- Difficulty communicating and interacting with other people

- Finding it hard to recognise and understand other people’s emotions

- Finding bright colours and loud noises uncomfortable or stressful

- Anxiety in unfamiliar situations

- Taking longer to process and understand information

- Repeatedly doing or thinking the same things

Attitudes and unconscious bias displayed by a practitioner can act as an obstacle in the communication process. Factors here include respect, culture and assumptions based on personal bias or stereotyping. Establishing rapport and building trust with a patient is important for the eye exam and dispensing process to be successful; therefore, it is vital to be able to put aside any preconceptions.

Feedback is the message sent back by the recipient, as they have perceived it.7 Feedback is essential, as without this reaction it is impossible to know if the message was understood correctly. A patient may ask the practitioner to repeat what they have said, equally, non-verbal communication such as a frown or a nod can provide valuable feedback. Having asked a question, it is important that the practitioner waits for a reply; this may sound obvious, but it can take some people with LD longer to reply. Good listening skills and the ability to identify and respond to non-verbal cues can have a significant impact on the effectiveness of the communication process.

Choice of language is also crucial to effective communication. Using specialist optical jargon or abbreviations can create an obstacle in the communication process.8 Similarly, the style of language used must be chosen sensibly. The level of education and knowledge of the patient, parents and carers should be considered, as well as their social and cultural background. Eye care professionals should be honest about how much of the conversation they understood and always give the other person an opportunity to explain points that have not been understood or ask for support.

When having a discussion with a person with LD, patience is very important. While it can be tempting to finish off the patient’s sentences as a way of speeding up the conversation, some people can find this irritating. Instead, the patient should be given an opportunity to demonstrate their preferable communication method(s), thus making communication more successful.9

More than 50% of the meaning of a message is conveyed through non-verbal interactions7(figure 2). These include body language, such as hand gestures, posture, facial expressions, tone of voice, dress code, eye contact and personal space. On the other hand, non-verbal cues can be easily misinterpreted as meaning can vary, so it is worthwhile exercising caution when relying predominantly on non-verbal communication.

Figure 2: Non-verbal communication interactions

The practitioner should determine how the person indicates ‘yes’ and ‘no’. This may not necessarily be through the typical nodding or head shaking. During a conversation it is advisable to face the other person and make eye contact. However, it should be noted that not all children and adults will be happy, or able, to maintain eye contact; those with autism may find this particularly difficult. Finally, it is essential to check for understanding at regular intervals, recap the key information and provide the patient with easy read material if necessary.9

Communicating with Children and Adults with Learning Disabilities

To provide effective eyecare to individuals with LD, all practice staff must have a basic understanding of their needs. When scheduling an appointment, inform the team that the patient has LD so that support staff can ask relevant questions during the initial phone conversation with the carer. Pre-visit materials, such as pre-assessment questionnaires, are helpful for gathering background information.10 A preliminary phone call can also assist the eyecare practitioner in their preparation by asking about the patient’s past experiences, preferences, challenges, access issues and the availability of a communication passport.10, 11

Knowing as much as possible about the patient beforehand is crucial, as the carer accompanying them might not have accurate medical information. Consider booking a longer appointment, which is a relatively easy reasonable adjustment to accommodate the more time-consuming examination and reduce time pressures.

In most cases, optometrists and dispensing opticians will be dependent on the person supporting the patient to help them communicate; however, it is advisable to be prepared by finding out about the preferred method of communication and speak directly to the patient.9

A communication passport is a record of how an individual communicates, rather than a communication method.11 It reflects the person’s personality, including their likes, dislikes, needs, wants and aspirations. These passports offer a practical, person-centred, way to support those who cannot easily speak for themselves by summarising their communication style in an accessible format.11

The goal is to ensure this information is available to those working with the person and to prevent information loss, for example when a child transitions between primary to secondary education. Typically, communication passports are on paper or laminated card, created by hand or using online resources, but they are increasingly becoming multimedia documents, including audio and video files.12

A communication passport may not be the sole document detailing an individual’s support needs; such information might also be in a health action plan or person-centred plan. All relevant information might be combined into one document, or an individual could have multiple documents. For instance, someone might have a detailed passport at home and a more specific version for hospital visits, focusing on health-related information or routine tests.

Systems such as Sign Supported English (SSE)13 (signing following the English language syntax and speaking English at the same time) and Makaton14 are often the first forms of alternative communication methods introduced in special provision schools. Makaton is a sign language programme that incorporates signs and/or symbols alongside speech. The word order follows spoken English, and signs support the understanding of key spoken words in interactions; for example, in the phrase “a girl is eating a cake,” the signs for ‘girl,’ ‘eat,’ and ‘cake’ would be used.14

Patients with LD may use a limited set of signs tailored to their specific needs and adapted for any physical limitations in hand and body movement. These personalised signs may be easily recognised by someone familiar with the individual, like a family member or teacher; however, optical professionals may need to be shown what each sign means. The Makaton system also includes printed formats, so a familiar sign like ‘home’ has a corresponding printed version.14 These signs are often seen in schools or in easy-to-read information.

For people who are sight impaired, signing from a distance may not be feasible. In such cases, on-body signing14 can be used, where one person places their hands lightly on or under the other’s hands to ‘read’ the signs being made. Often, these signs are modified versions of Makaton or unique personalised signs. On-body signing can also be preferred by someone who is more tactile.

Aided communication covers a range of methods that involve an additional device beyond the two people communicating. This could be a simple object or a sophisticated electronic device. Objects of reference can represent an activity, an idea or a person. For example, a coat could communicate the idea of going out and a spoon could mean that it is lunchtime. Eventually, once the person develops an understanding of some objects of reference, the real objects may be replaced with images; this approach can help the person communicate their choices and express opinions from a young age.

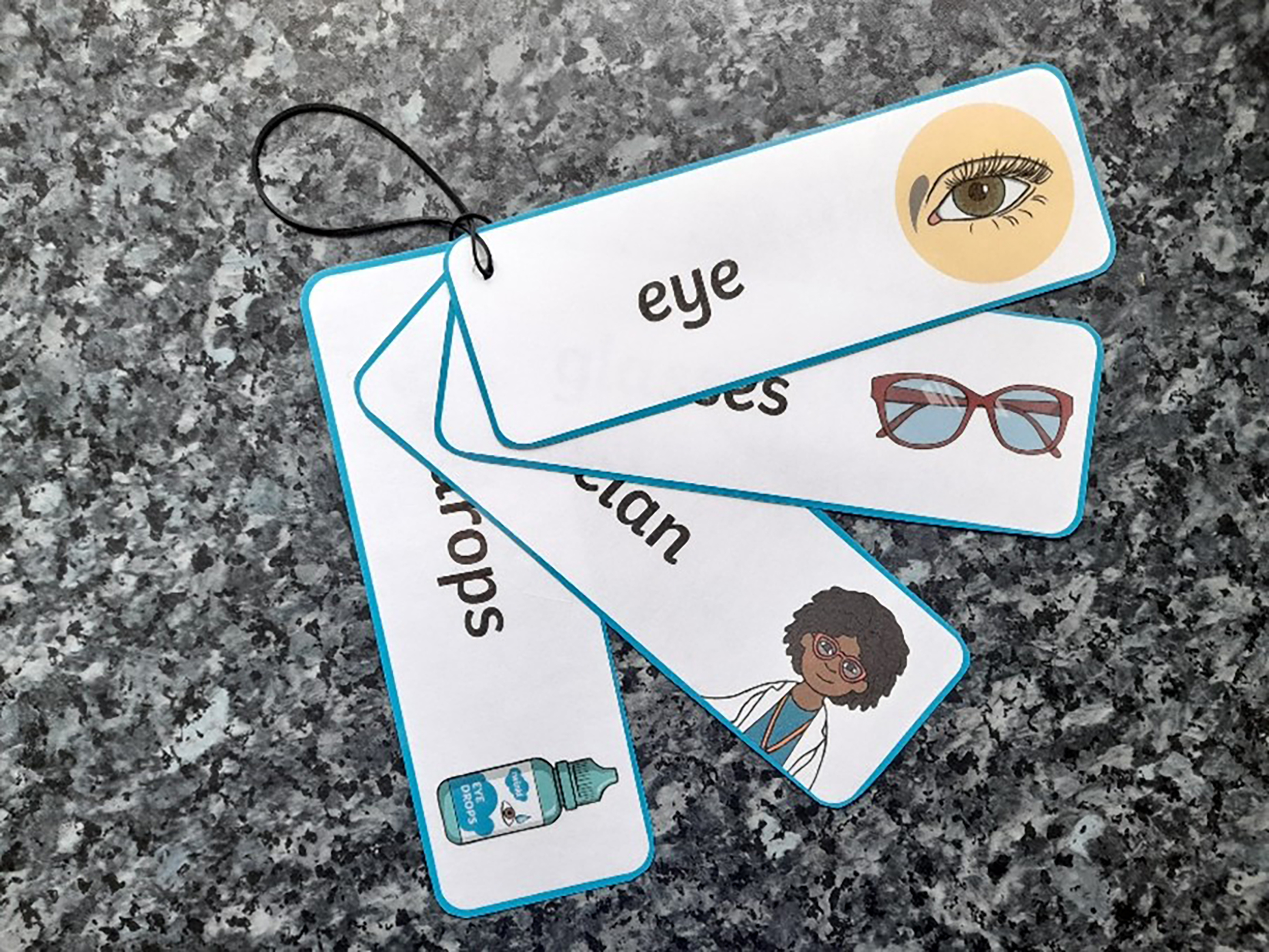

Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS)15 is a more complex method that uses symbols to establish a two-way communication. Flashcards with pictures representing different activities are often used by teaching staff within the special schools setting. Similar sets of cards describing staff members, testing room equipment or spectacle frames can be created and used by the eyecare professionals in practice (figure 3).

Figure 3: Picture exchange communication cards

The Accessible Information Standard

‘The Accessible Information Standard aims to make sure that people who have a disability, impairment or sensory loss get

information that they can access and understand, and any

communication support that they need from health and

care services’16

The Standard guides organisations on how to ensure that patients, service users, their family members and carers can access and comprehend the information they are given. This includes providing information in accessible formats. Additionally, the document instructs organisations on how to ensure individuals receive support from communication professionals, when needed, and on modifying working practices to facilitate effective communication. By law, all organisations providing NHS care or adult social care must follow the Standard from August 1, 2016.16

As part of the Accessible Information Standard, organisations that provide NHS care or adult social care must do the following:16

- Ask people if they have any information or communication needs and find out how to meet their needs.

- Record those needs clearly and in a set way.

- Highlight or flag the person’s file or notes so it is clear that they have information or communication needs and how to meet those needs.

- Share information about people’s information and communication needs with other providers of NHS and adult social care, when they have consent or permission to do so.

- Take steps to ensure that people receive information which they can access and understand and receive communication support if they need it.

The Standard states that service users should have the ability to contact and be contacted by services in accessible ways, for example via email or text message.16 Additionally, they should receive information and correspondence in formats they can read and understand, such as audio, braille, easy read or large print.

Furthermore, patients and their families should be supported by a communication professional during appointments, if needed, to facilitate conversation, for example a British Sign Language interpreter. Finally, they should receive support from staff to communicate, for example to lip-read or use a hearing aid.

The aim of the Standard is to ensure that people with LD, impairment or sensory loss receive information that they can easily read or understand with support, enabling them to communicate effectively with health and social care services.17

Ask, Listen, Do18

By law, people with LD, autistic people, their families and carers have the same rights to high quality services and person-centred care as everyone else. However, achieving this can be challenging when they are not understood, listened to or given an opportunity to complain. Feedback from these individuals and their families indicates that current complaint systems are not working as intended.18

Effective communication allows people to feel valued, at ease and in control of their healthcare. The ‘Ask, Listen, Do’ project helps organisations and practitioners to understand how they can improve the experiences of these people. The project highlights the need to provide clear and accessible information, thus providing everyone with an equal opportunity to complain, raise a concern or give feedback.18

Furthermore, it stresses the importance of communicating with people using methods that work for them.18 People communicate in different ways, therefore sometimes involvement of the right person is required, such as a speech therapist, a family member or an advocate, to ensure everyone can participate. In addition to this, it offers suggestions of reasonable adjustments to support effective communication, such as reducing noise, considering accessibility and allowing extra time. It is important to acknowledge that people have other commitments, hence, whenever possible, schedule appointments around these commitments.

Being creative in finding ways to engage in positive conversations can be very helpful in establishing rapport and building trust. It is advisable to avoid using service-led language; instead, speak in terms of real-life situations. Unfamiliar technical terms and jargon can make people feel overwhelmed and uncomfortable.

A concept of ‘nothing about me, without me’ encompasses some of the key aspects of person-centred approach in healthcare,19 such as engaging patients in determining what reasonable adjustments are needed, thus ensuring active and inclusive participation from the outset. Eyecare professionals need to create opportunities for meaningful communication, foster positive and supportive environments in practice and respect their patients’ personal views and opinions.18

Understanding local protocols and referral pathways is important for both optometrists and dispensing opticians, the easiest way to do this is to simply get in touch or join your Local Optical Committee (LOC). Attending meetings or becoming a committee member is an ideal way to engage with other eyecare practitioners and have an input into the development of local protocols.

Making reasonable adjustments17

General

Communicate with the patient, where possible, and consider more than one appointment if necessary to complete the eye test.

Making the appointment

Designate a nominated lead for learning disabilities and make staff aware of what changes can be made.

Adjustments to consider:

- Early/late appointment, depending on the patient preference.

- Avoid keeping the patient waiting.

- Arrange a visit to the practice/hospital department prior to appointment.

- Split the appointment if additional tests are required, thus reducing time in eye clinic.

- Where drops are required, if possible, consider home instillation.

Patient information

Discuss with the carer or, where possible, the patient the following information:

- • Current patient medical condition(s).

- • Current patient’s visual performance.

- • Consider any difficulties the patient might experience during the examination.

- • Find out how the patient feels about being touched.

Arrival at the practice/clinic

- Ensure reception staff are aware of adjustments that can be made.

- All staff alerted as patient checks in and quiet area available.

- Optometrist alerted so that they can prioritise patient and minimise wait.

- Optometrist to have room ready prior to patient arrival.

- Appropriate vision tests and assessments decided in advance, thus minimising time in clinic.

Examination and vision assessment

- Explain what is going to happen.

- Warn the patient before turning lights off.

- Warn patient before they are touched.

- Consider different ways of achieving what is needed.

- Alternative ways of checking eye pressure.

- Minimise the use of eye drops, whenever possible.

- Functional vision assessment:

- Are there any concerns regarding vision?

- What has changed for the patient?

- What activities does the patient now find difficult?

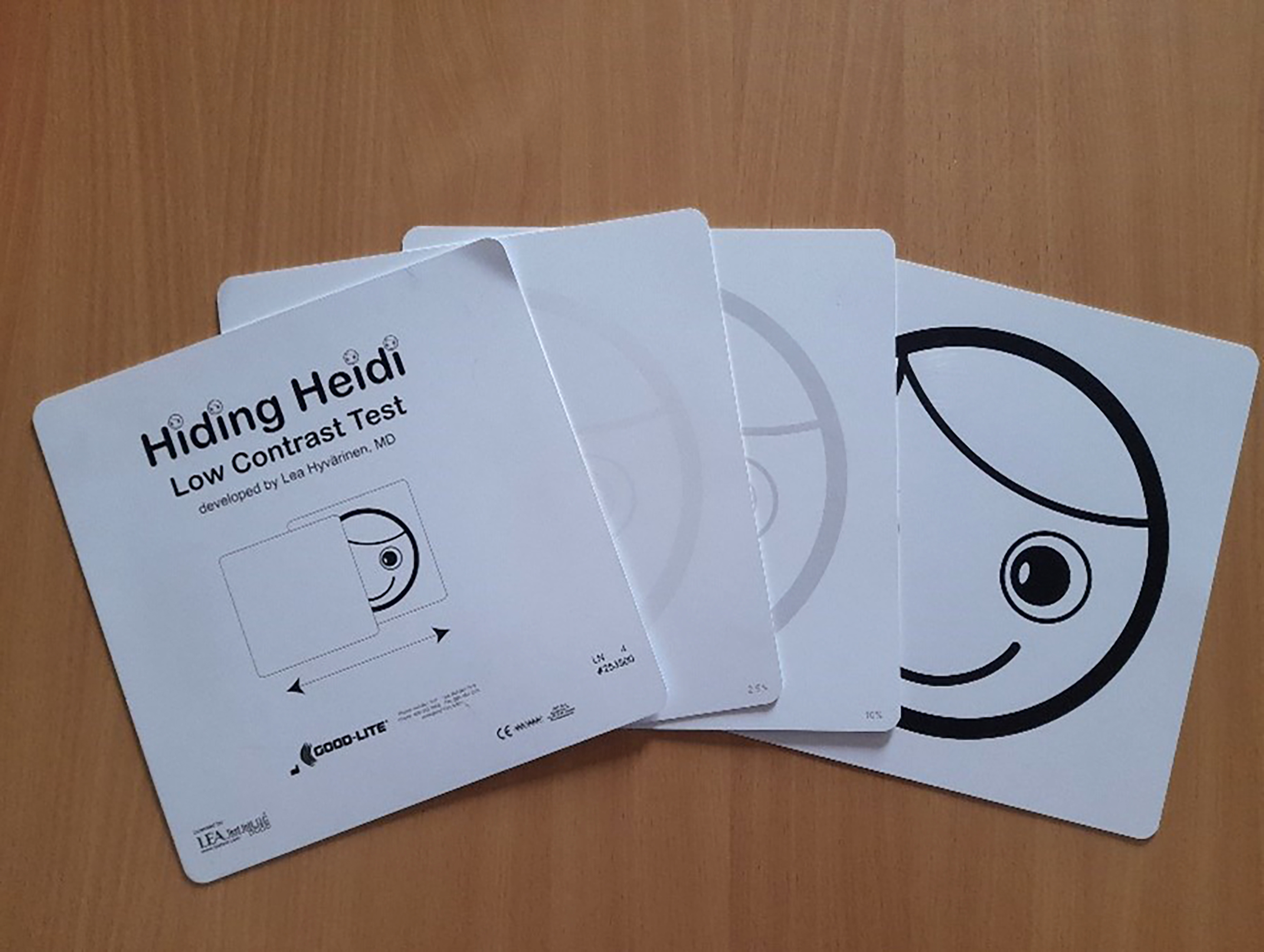

- Visual acuity assessment, preferential looking, matching shapes (Figure 4,5,6).

Figure 4: Visual acuity assessment

Figure 5: Low contrast test

Figure 6: Matching shapes

Spectacles

- Glasses for eating are as important as glasses for reading; patients who cannot read should not be denied glasses to help them see close up.

- Glasses should be discretely labelled with the patient’s name if they live in a shared setting and with their purpose (near or distance) if they have more than one pair.

Conclusion

So, what can be done in practice to ensure patients with LD have a positive experience? Using clear communication methods to suit individual needs, and making reasonable adjustments, will ensure the best outcome for these patients. Additionally, raise awareness with all optical staff, and regularly organise staff training on communication and how to best support people with LD. Ensure support staff use appropriate materials (SeeAbility) when collecting patient information and discuss the type of questions asked during telephone conversations.

Before the appointment, speak to family or carers to understand how the person communicates and check if there is a communication passport available. Inquire about any access issues and preferences or dislikes in the clinical setting. Consider scheduling a longer appointment to ensure a more relaxed experience.

Whether there is an eye condition that needs to be treated or managed, or a vision impairment present, eye care providers must ensure that everyone concerned with the patient’s health and wellbeing has a clear understanding of their individual needs, the treatment or management plan and what effective adaptations can be made when delivering care.

Accessible eye care services require careful planning, with an ultimate goal of enabling everyone to make the most of their vision. Connecting with LOCs and getting involved in the development of local protocols provides optometrists and dispensing opticians with an ideal opportunity to ensure eyecare services are as accessible as possible and offer the best outcomes and experiences for all patients.

- Maryna Hura has worked for Boots Opticians since 2003, she qualified as a Dispensing Optician in 2008 when she also joined the Ophthalmic Dispensing team at Bradford College. Hura completed her teaching qualification in 2013 and Masters in Education in 2018. She also achieved Level 1 qualification in British Sign Language (BSL) in 2019, Level 2 in 2020 and is currently working towards a Level 3 certificate. Hura has been a member of the GOC Education Visitor Panel since 2018 and is also a member of the Leeds LOC, Huddersfield Deaf centre committee (Secretary) and a fellow of the Higher Education Academy HEA).

References

- Public Health England. Eye care and people with learning disabilities: making reasonable adjustments. 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/eye-care-and-people-with-learning-disabilities/eye-care-and-people-with-learning-disabilities-making-reasonable-adjustments [Accessed 18th June 2024]

- Seeability. Wearing glasses. Available from: https://www.seeability.org/eye-care/wearing-glasses Accessed [18th June 2024]

- Holmes JM, Lazar EL, Melia BM, Astle WF, et al. Effect on response to amblyopia treatment in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011; 129(11): 1451-1457. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.179

- Emerson E, Robertson J. The estimated prevalence of visual impairment among people with learning disabilities in the UK. Learning Disabilities Observatory report for RNIB and SeeAbility. 2011. Available from: https://media.rnib.org.uk/documents/Estimated_prevalence_of_VI_among_people_with_LD_in_UK_-_Research_report.pdf Accessed [18th June 2024]

- Donaldson LA, Karas M, O’Brien D, Woodhouse JM. Findings from an opt-in eye examination service in English special schools. Is vision screening effective for this population. PloS one. 2019; 14(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212733

- Blair J. Diagnostic overshadowing: see beyond the diagnosis. British Journal of Family Medicine. 2017;17:34-5.

- Mindtools. Barriers to effective communication. Available from: https://www.mindtools.com/auu6hxk/barriers-to-effective-communication Accessed [18th June 2024]

- Lee AC, Herrieven E, Harrower NA. Health inequalities for people with learning disabilities: why it matters and what emergency physicians need to know. British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2024; 85(2). https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2023.0357

- Karas M, Laud J. The communication needs of people with profound and multiple learning disabilities. Optometry In Practice. 2015; 16(2). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marek-Karas/publicati on/337445305_The_communication_needs_of_people_with_profound_and_multiple_learning_disabilities/links/5e75f1eda6fdcccd62127754/The-communication-needs-of-people-with-profound-and-multiple-learning-disabilities.pdf

- Seeability. Resources. Available from: https://www.seeability.org/resources?resource_specialism=10&page=1 [Accessed 18th June 2024]

- Millar SV, Aitken SA. Personal communication passports: Guidelines for good practice. Edinburgh: Call Centre; 2003.

- Goldbart J, Caton S. Communication and people with the most complex needs: What works and why this is essential. Mencap. 2010. Available from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/198309/1/Mencap%20Comms_guide_dec_10.pdf [Accessed 18th June 2024].

- Sense. Sign Supported English (SSE). Available from: https://www.sense.org.uk/information-and-advice/ways-of-communicating/sign-language/#:~:text=Sign%20Supported%20English%20(SSE)%20is,same%20grammatical%20rules%20as%20English. [Accessed 18th June 2024].

- Makaton. About Makaton. Available from: https://makaton.org/TMC/AboutMakaton.aspx?hkey=c8a4263d-78cc-4c30-b135-153eb6ac3118 [Accessed 18th June 2024]

- Bondy AS, Frost LA. The picture exchange communication system. Semin Speech Lang. 1998;19(4):373-88; quiz 389; 424. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1064055. PMID: 9857393.

- NHS England. Accessible Information Standard – Overview 2017/2018. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/accessible-information-standard-overview-20172018/ [Accessed 18th June 2024]

- Department of Health. Turner S, Kill S, Emerson E. Making Reasonable Adjustments to Eye Care Services for People with Learning Disabilities. 2013. Available from: https://www.ndti.org.uk/assets/files/IHaL-2013_-01_Reasonable_adjustments.pdf . [Accessed 18th June 2024]

- NHS England. Ask Listen Do – feedback, concerns and complaints. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/learning-disabilities/about/ask-listen-do/

- Department of Health. Liberating the NHS: No decision about me, without me. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216980/Liberating-the-NHS-No-decision-about-me-without-me-Government-response.pdf [Accessed 18th June 2024]

- LOCSU. About Us. Available from: https://locsu.co.uk/about-us/ [Accessed 18th June 2024]

- National Autistic Society. What is autism? Available from: https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/what-is-autism [Accessed 18th June 2024]

- NHS. What is autism? Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/autism/what-is-autism/ [Accessed 18th June 2024]