Domains and learning outcomes

• One distance learning CPD point for optometrists, and dispensing opticians.

Clinical practice

(5.3) After successful completion of this CPD practitioners will be able to compare current myopia research evidence alongside professional responsibility and apply this to daily clinical practice

Leadership and accountability

(8.1) After successful completion of this CPD practitioners will recognise that patient records must include meticulous, clear, and contemporaneous detail of all myopia and myopia management patient discussions and be accessible to all those involved in the patient’s care

It is recognised that myopia is increasing globally at an alarming rate, with nearly five billion people or 50% of the world’s population predicted to be affected by the condition by the year 2050, including 10% with high myopia.1 Scientific study of myopia can be traced as far back 1604 to Johannes Kepler and has been described in a wide variety of ways, such as presumed aetiology, age of onset, progression pattern, amount of myopia (in dioptres [D]) and structural complications.2

Eye care professional (ECP) engagement with myopia management (MM) according to the last International Myopia Institute (IMI) global cross-sectional survey has increased.3 Single vision spectacles and soft contact lenses were still reported as being the most prescribed correction, average 43% and under correction still used by more than one in 10 ECPs at least ‘sometimes’. Comparing results reported in 20154 (68%) and 20195 (52%), single vision prescribing is on a downward trend.

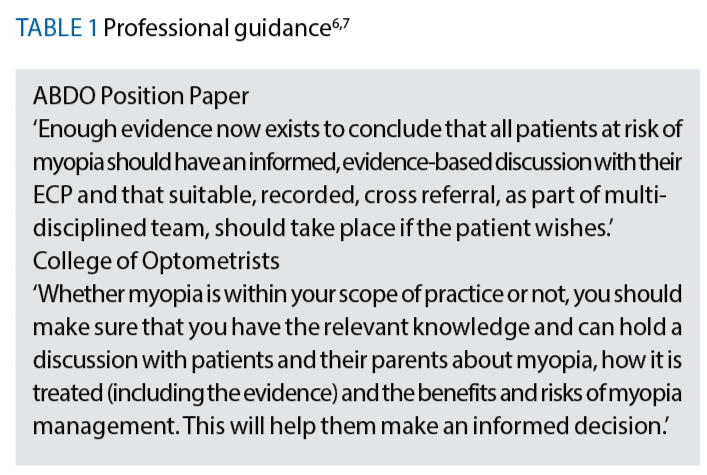

As registered healthcare professionals, optometrists, contact lens opticians and dispensing opticians are expected to incorporate an evidenced-based approach to clinical practice. This means, keeping up to date with the latest research evidence, and being aware of the guidance set out by professional bodies, Association of British Dispensing Opticians (ABDO),6 and College of Optometrists (CO)7 see table 1. The General Optical Council (GOC) Standards of practice for optometrists and dispensing opticians (s.5.3)8 also specifically sets out registrant responsibilities regarding keeping up to date with current research and implementing this into routine clinical practice see table 2.

This article looks at the registrant responsibilities regarding myopia and myopia management and the challenges faced in practice keeping up to date with new research, as well as understanding the different types of research and how research is important in informing our discussions with patients, parents and carers.

This article looks at the registrant responsibilities regarding myopia and myopia management and the challenges faced in practice keeping up to date with new research, as well as understanding the different types of research and how research is important in informing our discussions with patients, parents and carers.

In the authors’ opinion from CPD sessions over the last year, there appears to be a clear move to embedding MM into daily practice demonstrating growing practitioner confidence identifying and managing progressing myopes. Although for some practitioners, myopia discussions with patients, parents and carers are just beginning to take place highlighting there is still inconsistency in provision of MM across the UK, which was confirmed by a recently published qualitative study by Coverdale et al (2024).9

This study conducted among online focus groups of ECPs from both UK primary and secondary care providing insights into practitioners’ views regarding provision and potential barriers in prescribing MM.

It found that the greatest communication barrier was affordability, especially for those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.9 There was also scepticism over efficacy within information produced by manufacturers, but it was accepted that there was considerable research published on MM.

While it is important to consider what products or treatment options manufacturers offer by familiarising yourself with their brochures and lens specifications it is essential to ask for the research evidence that supports their product.

When critically appraising research it is the readers responsibility to determine if there is any bias in either the sampling, testing methods, or reporting of results for any research paper and retaining scepticism can help objectivity in this process.

For those less experienced in critically appraising research there are useful online resources for example, Critical Appraisal Check List Programme (CASP),10 which provides checklists for different research methodologies.

Peer reviewed studies (reviewed by peers in that field) help to ensure accuracy, validity and quality, here are some examples of peer reviewed journals; Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Ophthalmology; British Medical Journal (BMJ) Open; Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics; Eye; Clinical Ophthalmology; Clinical and Experimental Optometry.

The IMI is also an excellent source of information as it consists of a group of global experts that have produced evidence-based recommendations classifications, patient management and research in the form of IMI white papers, which are free to access.11 Series three of the IMI papers are now available.

Research methodologies

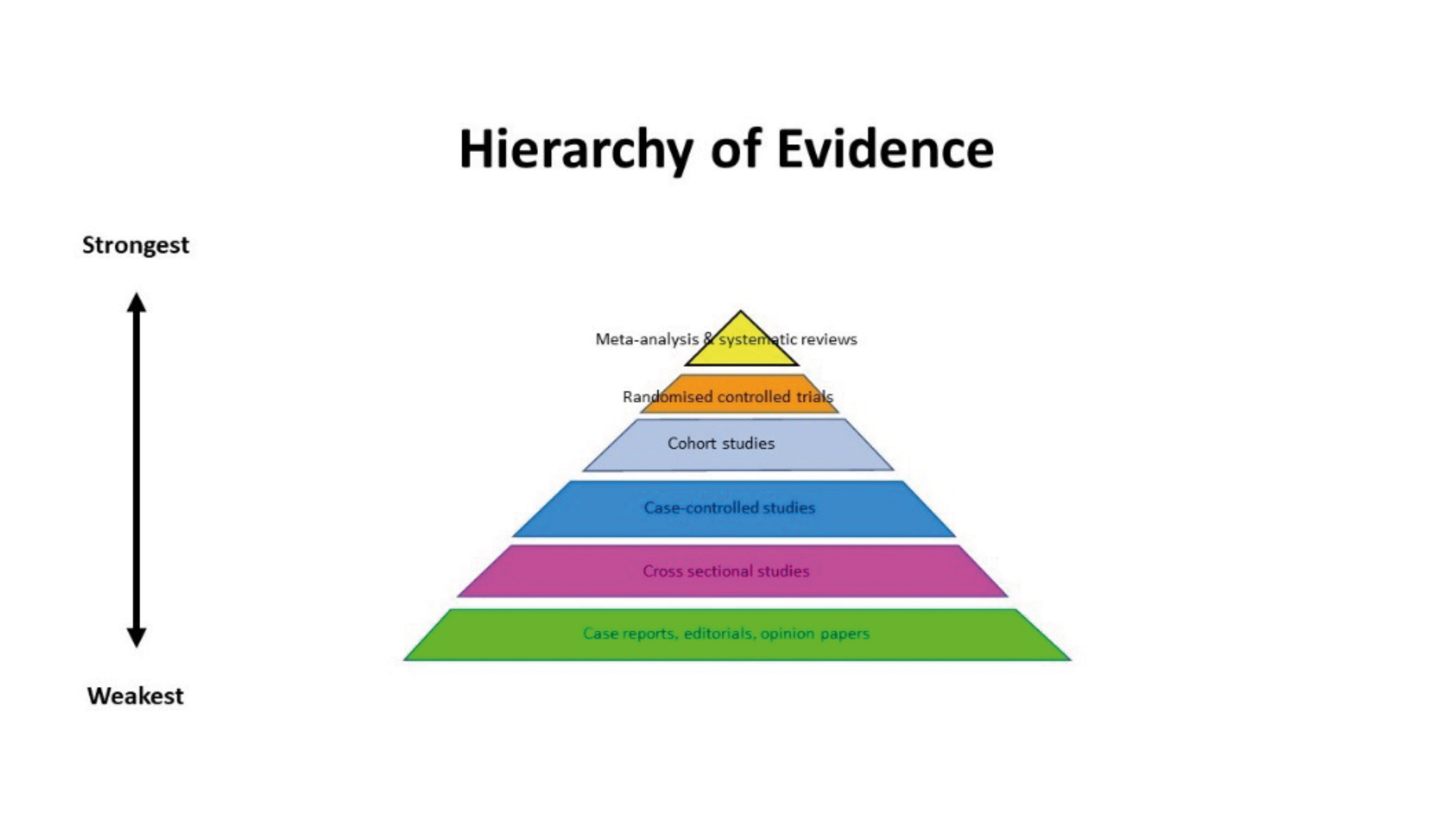

There is a considerable amount of available research on myopia and myopia management, so it is also important to consider the hierarchy of evidence12 (figure 1, below) for example, the best way to determine efficacy is from randomised controlled trial (RCT) a quantitative research methodology.

At the top of the pyramid are systematic reviews, which is a synthesis of all available research evidence (relevant to a specific research question) using a structured and repeatable methodology. A systematic review may also contain meta-analysis a statistical technique used to combine the results of multiple studies allowing researchers to identify overall trends and draw more robust conclusions.13

Qualitative research is also crucial in healthcare because it provides deep insights into patient experiences, emotions, and motivations.14 Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data, qualitative methods such as interviews and focus groups capture the nuanced perspectives of patients and healthcare practitioners.

This approach helps identify underlying reasons for behaviours, such as why patients may not adhere to treatments or how they perceive their illnesses. By understanding these factors, healthcare practitioners can tailor interventions to better meet patient needs, improve patient satisfaction and enhance the overall quality of care.15 Additionally, qualitative research can uncover areas for improvement that might not be evident through quantitative methods alone.

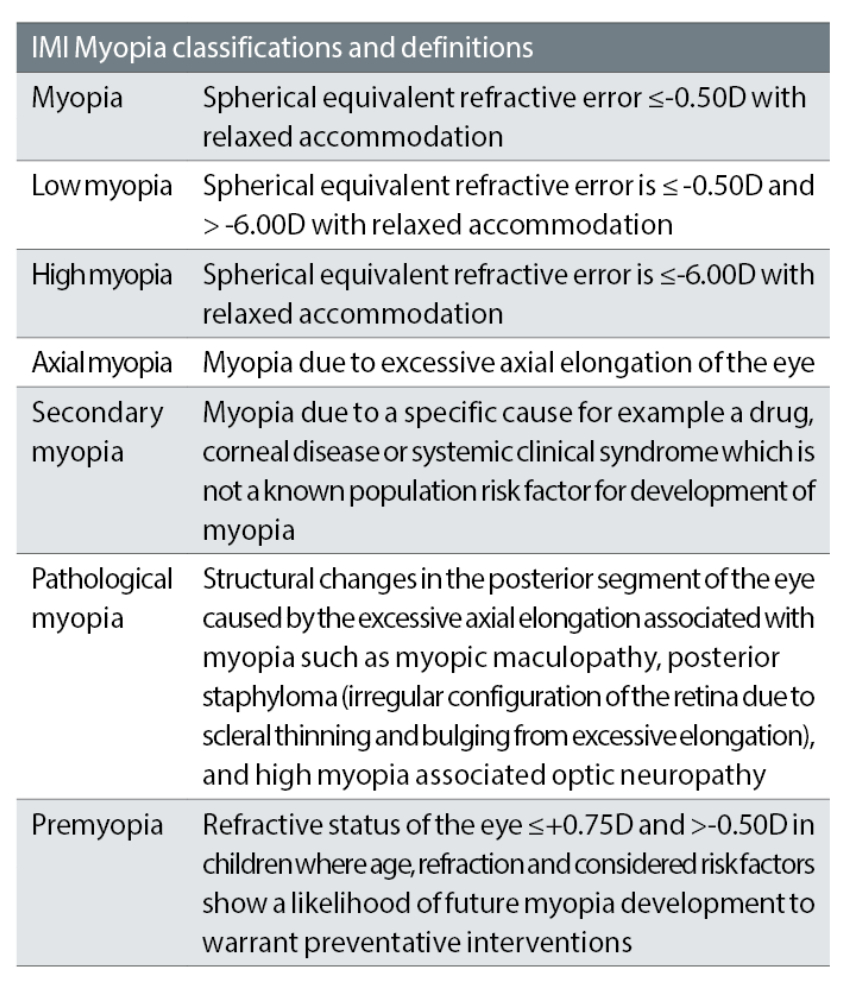

Table 3: Myopia classifications and definitions16

Firstly, is important to understand the current terminology and definitions of myopia creating consistency, table 3 explains the IMI definitions and classifications16 using mathematically valid descriptors, for high myopia ≤ -6.00D meaning more myopic than -6.00D.

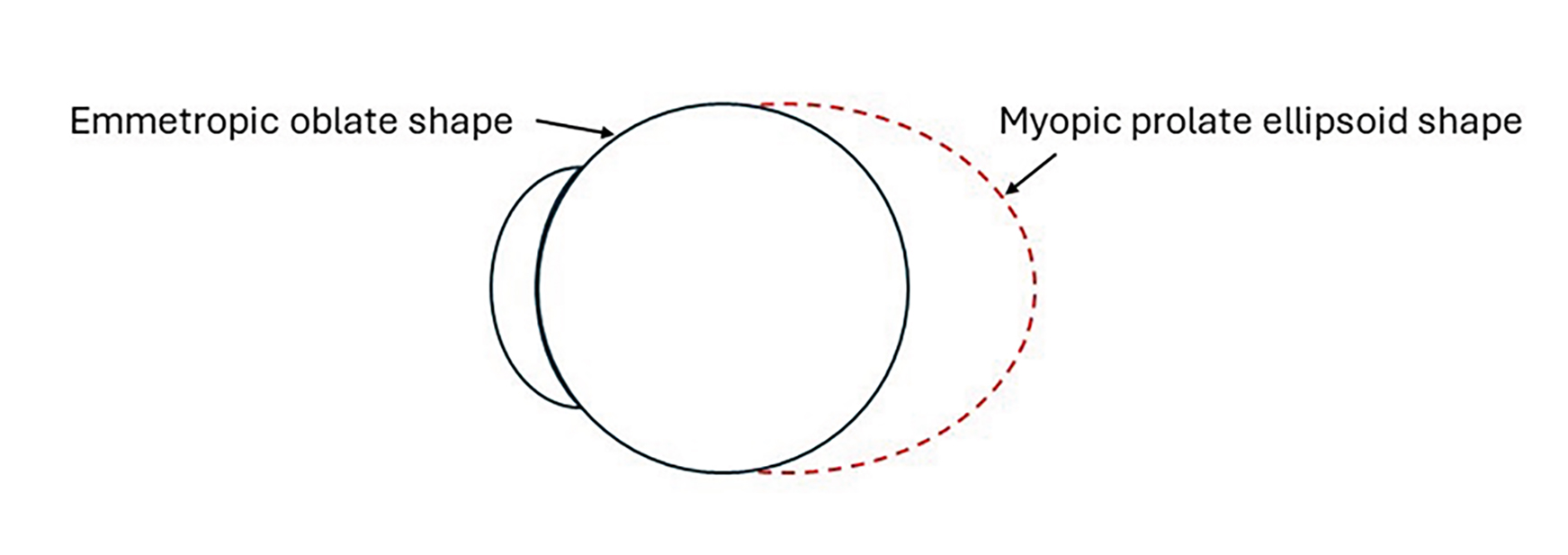

Myopic axial elongation causes the shape of the eye to change from oblate or spherical to a prolate ellipsoid shape meaning the centre of the ocular wall is located posterior to the equator, with horizontal and vertical dimensions affected to a lesser extent17, 18 (figure 2).

Figure 2: Ocular shape of an emmetropic and myopic eye

Risk Factors for Developing Myopia

While the strongest association for myopia in children is parental myopia the specific genetic variants underlying myopia are still not completely understood. There are slightly different figures quoted between studies but Jones et al (2007)19 found an odds ratio of 2.17 and 5.40 for children with one or two myopic parents, respectively. Odds ratio (OR) is a statistical measure used in healthcare research to quantify the strength of association between an exposure and an outcome.

Environmental, lifestyle and behavioural factors are now known to be key factors in the increasing prevalence figures. Myopia risk is increased for children who spend less than two hours per day outdoors20 also, increasing a child’s time outdoors by approximately 76 minutes per day can reduce the risk of incident myopia.21 On the subject of how time outdoors produces a protective effect as well as potentially mitigating myopic progression by increasing time outdoors is a topic in itself. Although the protective effect of time outdoors is thought to be linked with light levels.22

Education is consistently suggested as a risk factor,23 the more education, the more myopia, but a definitive mechanism remains unclear as there are often confounders that also need to be considered like more education can mean less time outdoors and more near work.

In a study by Mountjoy et al (2018),24 Mendelian randomisation (MR) was used to determine whether more years spent in education cause myopia or if myopia leads to more years in education. MR leverages genetic variants as proxies for environmental exposures to infer causality. The researchers performed bidirectional MR analyses.

First, they examined if genetic predisposition to myopia influenced years of education. Second, they assessed if genetic predisposition to higher education levels affected refractive error (a measure of myopia). The results showed that each additional year of education was associated with a more myopic refractive error of -0.27D per year.24

Conversely, there was little evidence to suggest that myopia influenced educational attainment. This study highlights the utility of MR in disentangling complex causal relationships, providing robust evidence that prolonged education is a causal risk factor for myopia.

Indoor time clearly involves a greater demand on ocular accommodation with the use of digital devices, reading and writing. Accommodative lag has been thought of as a mechanism that drives myopic progression but Mutti et al (2006)25 found that lag of accommodation occurred simultaneously with the development of myopia.

Binocular vision status should always be assessed as it improves retinal image formation and the accommodative response to defocus.26 Higher accommodative convergence to accommodation (AC/A) ratio have also been found in children with myopia when compared to emmetropic children.27

Age and refractive status are significant as the amount of hyperopia prior to emmetropia, known as hyperopia reserve (HR) measured as spherical equivalent (SE), may be a key predictor for the early onset of myopia.28 The CLEERE Study, provided suggested base line cut off points varying with age from < +0.75 D at age six years, ≤+0.50 D at ages seven to eight years, ≤+0.25 D at ages nine to 10 years, and ≤ 0.00 D at age 11 years.29

This aligns with the IMI definition for premyopia.13 Therefore, a child aged six years with less than +0.75D of hyperopia is at an increased risk of developing myopia, this should be considered alongside other myopia risk factors.

Long term ocular health concerns related to myopia

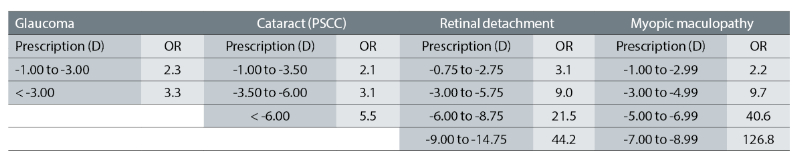

It has been clearly documented that being myopic places an individual at an increased risk of sight-threatening diseases, being highly myopic (≤-6.00DS) increases the risk of these sight threatening diseases/pathologies. Flitcroft (2012)30 is a frequently quoted study providing odds ratios for myopia related pathologies compared to that of an emmetrope, see table 4.

Table 4: Summary of the Flitcroft odds ratios for myopia related pathologies30

It is important to make patients aware of these potentially sight-threatening conditions and that their risk appears to be proportionate their degree of myopia. The figures in table 4 highlight the need for discussions on myopia at the earliest opportunity as for prescriptions between -3.00D to -5.75D the risk of retinal detachment is nine times that of an emmetrope.

These OR figures certainly become relevant when considering the young adult that is undertaking a period of intense study even when their prescription falls within the category of low myopia but is demonstrating myopic progression.

The CO in consultation with ABDO published their March clinical file on myopic management guidance for practice teams when dealing with external prescriptions, this joint approach is welcomed ensuring both optometrists and dispensing opticians are supported by clear consistent guidance.31

Challenges

As discussed at the beginning of this article, MM provision is inconsistent across the UK9 so for some practitioners they are just beginning to have myopia discussions with patients and parents. Patients and parents look to ECPs as the ‘experts’ regarding eye care, which for some practitioners will mean undertaking new or updating existing learning, reviewing research evidence and professional guidance, becoming familiar with the now extensive range of MM licenced treatment options as well as individual myopia risk factors.

Training needs to extend to all practice staff as consistent messaging is essential. Discussions should routinely take place between ECPs embedding the latest research and guidance into routine clinical practice. Written information should be made available to patients to reinforce discussions, and for those that wish to conduct their own research recommendations of appropriate websites and organisations for example, MyKidsVision mykidsvision.org is an excellent patient-facing website.

The practitioner version is MyopiaProfile, which provides comprehensive reviews of currently published research. For those that do ask for more technical information the IMI offers an extensive range of unbiased reports (white papers) produced by the leading global experts.

One of the best ways to learn about MM is undertaking CPD, there are some excellent peer review and discussion workshop sessions currently available.

Discussions with peers in the authors’ opinion is an ideal learning format for the following reasons: peer review provides the opportunity of knowledge sharing of real-life case studies and experiences; improved clinical decision-making; enhanced communication skills by learning to listen to others’ viewpoints and articulating your own thoughts; reflective practice, which allows ECPs to evaluate their own performance as well as identifying areas for improvement. As Benjamin Franklin said: ‘Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn.’

Knowledge and confidence to discuss myopia and answer patient’s questions is fundamental to delivering professional eye care.

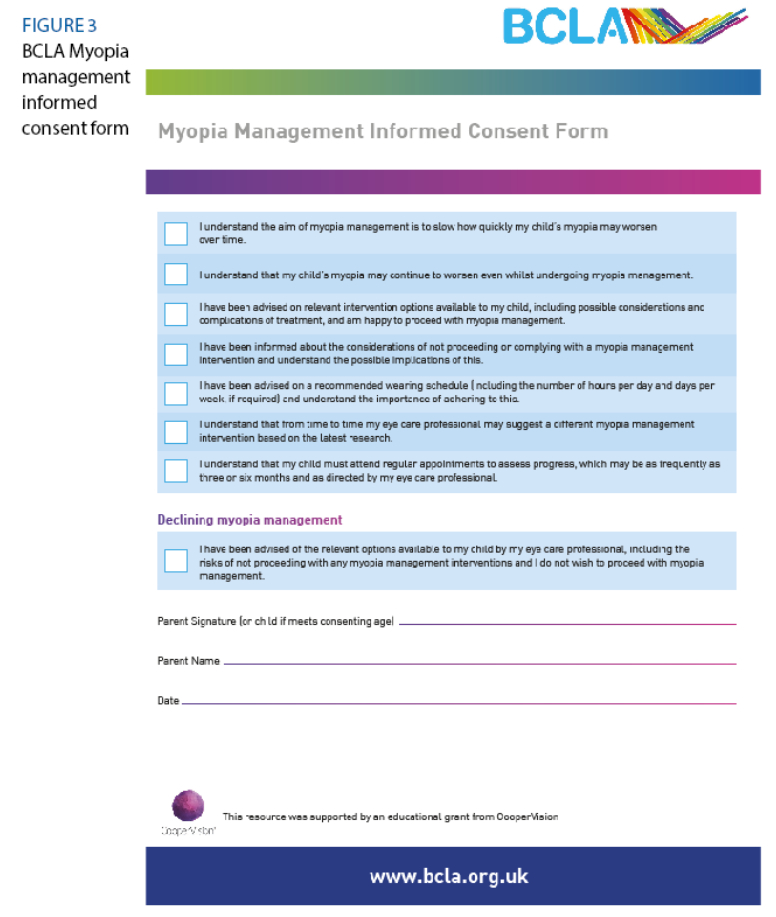

Informed consent

This is not something new to ECPs, informed consent is required before examining a patient providing treatment, or sale of an optical appliance. There is clear guidance regarding obtaining valid consent (s.3)8 and supplementary guidance on consent,32 some of the key standards are shown in table 2 (pictured, above). Many ECPs ask parents to sign a consent form (explicit consent) before commencing treatment, there are several templates available one such example is from the British contact Lens Association (BCLA).33 It should be remembered that informed consent is) ‘part of an on-going discussion and decision-making process’ (figure 3).

Record keeping

Maintaining clear, contemporaneous records (S.8.1) of all discussions, advice and treatments is essential and allows any ECP that follows a clear understanding of what has already taken place ensuring continuity of patient care.

In situations where either a MM contact lens or spectacle lens has been prescribed but for some reason the patient/parent decides against the suggested treatment option for example, due to concerns regarding cost this should documented.

All ECPs must always recommend treatments or optical devices that are clinically justified and, in the patient’s, best interest (S.7.6).8 In this circumstance, the patient should not be made to feel guilty, but advice given to ensure the patient and parent understand the importance of constant wear of their most up to date single vision prescription ensuring the patient is fully corrected.

Encouraging the patient to return if the spectacles should require any adjustment again ensuring visual exposure to the full correction. Advice should also be given on lifestyle choices, spending at least two hours per day outdoors,20 away from digital devices. The patient/parent should also be encouraged to return at any time if they do wish to proceed with MM.

Measuring axial length

Refractive error is how myopia is normally defined in practice but as myopic progression for children can be almost entirely attributed to axial length it is this measurement that is significant.

Accurate measurement of axial length using an optical biometer is ideal as it provides base line data and the ability to monitor progression but not all practices have access to this equipment.

For those that do not have a biometer, it is possible to estimate axial length using keratometry with refractive error, Morgan et al (2020) found this does provide a good estimate of absolute axial length.34 CooperVision provides an online axial length estimator,35 another interesting site to visit is the Brien Holden Vision Institute (BHVI),36 which uses a myopia calculator and plots myopic progression with and without myopia management. These are very useful resources for those without optical biometers.

Prescribing off label

Even for those that have been actively involved in MM for some time prescribing off label may appear daunting this will depend entirely upon current knowledge and experience also; practitioners are also reminded to recognise and work within the limits of your scope of practice (S.6.1).8

The IMI – Onset and Progression of Myopia in Young Adults37 white paper provides valuable insight into myopic progression among adults, especially those undertaking a period of intensive study. Those practices that are located near to a university are more likely to see young adults (18-22 years old) experiencing myopic progression.

According to Bullimore and Brennan (2024),38 ‘there is no safe level of myopia’. Considering the odds ratios for myopia-related pathology presented earlier a patient aged 20 years old undertaking further study with a prescription around -3.50D and showing myopic progression it is clear myopia and MM discussions should be taking place with their ECP.

The important considerations here are that prescribing for this patient will be ‘off label’ and it should be made clear to the patient that currently there is no evidence base to support MM in this age group and advertised efficacy figures will not apply. The key points are to ensure there is informed consent and apply meticulous record keeping. It is also recommended to have a discussion with the relevant manufacturer to check if the warranty would still apply relating to lens replacement.

The other patient group to consider is the premyope, remembering a child aged six years old with less than +0.75D of hyperopia is at an increased risk of developing myopia. Clinical decision-making will clearly be made on a case-by-case basis with considerations of other underlying risk factors taken into account.

A discussion on myopia should be undertaken and it is often a good approach to ‘plant the seed’ providing the patient/parents with information and resources they can go away and review, not forgetting that recommending time outdoors is free. And promotes healthy lifestyle. Caledonian Optical Imperium myopia management lens is available from +0.50D.39

Myopia Discussions

All discussions should be evidence-based and delivered using clear language that the patient would use, avoiding the use of ‘technical jargon’ also provide leaflets, as well as online resources to aid patient understanding. Good communication skills are essential actively listening to patients and responding to any concerns.

A frequent patient complaint when receiving information is the clinician being negative and rushing discussions. Be open and honest regarding the evidence remembering to explain that MM treatment options will help ‘slow’ the progression of myopia, but it cannot stop it.

Use examples of what to do and how to do it, which will help parents to adopt the strategy of improving their child’s visual diet encompassing increased time outdoors, limiting their time on digital devices and near vision tasks, all these things will help but will in themselves be unlikely to mitigate myopic progression.

Include within the discussion that efficacy is dose-related so patient compliance is required and MM treatment will require more follow-up visits to the practice. Whether it is contact lens comfort or accurately fitting spectacles these must be continually assessed to ensure optimum effect.

Patients and parents need to be aware that while myopic progression slows with age myopia stabilisation will differ for everyone, with variations between ethnicities, and some patients still progressing in their twenties.41 Myopic progression should also be considered over a 12-month period as more progression can occur during the winter months.42

Considering the strong evidence base and every dioptre matters, myopia discussions should be taking place where a patient is identified as myopic and at risk of myopic progression but if MM is not offered as an option in your practice a referral should be made to another practice providing this service. Subsequently, patient records should clearly outline the conversation with the patient and that consent was given for the onward referral.

In conclusion, despite the evident challenges in the provision of MM, the robust evidence base and professional guidelines underscore the duty of care and professional responsibility of ECPs. It is imperative that discussions regarding myopia are conducted with all patients who are myopic or at risk of myopic progression.

A comprehensive understanding of myopia terminology, definitions and potential risk factors for myopia-related pathologies will facilitate more confident and effective patient discussions.

Informed consent and meticulous record-keeping for all patient interactions are essential components of professional practice. These practices ensure that any subsequent ECP can accurately understand the patient’s history and provide continuity of care. MM presents an ideal opportunity for both dispensing opticians and optometrists to demonstrate their unique skill sets within the healthcare profession.

By staying informed about the latest research and treatment options, ECPs can ensure the best possible outcomes for myopic patients, thereby fulfilling their professional obligations and enhancing patient trust and satisfaction.

- Fiona Anderson BSc(Hons) FBDO R SMC(Tech) FEAOO is past president of the International Opticians Association, ABDO past president, past chair Optical Confederation, Optometry Scotland member, past Grampian AOC member, EAOO – co-opted trustee, ECOO European Qualifications board member, Renter Warden: Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers, Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers Liveryman & Fellow of the European Academy of Optometry & Optics.

- Tina Arbon Black, GOC number D-15212, is an experienced CPD author and presenter and is one of the clinical editors for Optician Magazine as well as a director of OrbitaBlack Ltd, an approved CPD provider that works with customers to produce CPD programmes. She is an ABDO College tutor, theory script marker and former ABDO practical examiner and frequently authors and delivers CPD for ABDO.

References

- Holden BR, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, Jong MJ, et al. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016; 123(5); 1036-1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006

- Kepler J. Optics (Ad Vitellionem paralipomena). Frankfurt: Claudius Marnius and heirs of Joannes Aubrius. 1604.

- Wolffsohn JS, Whayeb Y, Logan NS, Weng R, et al. IMI-Global Trends in Myopia Management Attitudes and Strategies in clinical Practice-2022 Update. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023; 64(6):6. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.64.6.6

- Wolffsohn JS, Calossi A, Cho P, Gifford K, et al. Global trends in myopia management attitudes and strategies in clinical practice. Contact Lens Anterior Eye. 2016; 39:106–116. https://publications.aston.ac.uk/id/eprint/27805/1/Myopia_management_attitudes_and_strategies_in_clinical_practice.pdf

- Wolffsohn JS, Calossi A, Cho P, et al. Global trends in myopia management attitudes and strategies in clinical practice—2019 Update. Contact Lens Anterior Eye. 2020; 43:9–17. https://publications.aston.ac.uk/id/eprint/40939/1/Myopia_Control_Attitudes_and_Practice_CLAE_2019_PURE.pdf

- ABDO. Myopia Position Paper. Available from: https://www.abdo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/224743-Position-on-Myopia-ABDO-Policy-Doc-JUL22-i.pdf [Accessed 9th July 2024]

- College of Optometrists. College publishes new guidance and evidence on myopia management 2022. Available from: https://www.college-optometrists.org/news/2022/august/college-publishes-new-guidance-and-evidence-review [Accessed 9th July 2024]

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. London: General Optical Council; 2016

- Coverdale S, Rountree L, Webber K, Cuffin M, et al. Eyecare practitioner perspectives and attitudes towards myopia and myopia management in the UK. BMJ Open Opth. 22024; 9: e001527. https://bmjophth.bmj.com/content/bmjophth/9/1/e001527.full.pdf

- CASP. Critical Appraisal Checklists. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ [Accessed 9th July 2024]

- The International Myopia Institute (IMI). White Papers. Available from: https://myopiainstitute.org/imi-white-papers-clinical-summaries/ [Accessed 9th July 2024]

- Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper 5th Edn. England: John Wiley & sons Ltd 2014; p. 41.

- Bowling A and Ebrahim S. Handbook of Health Research Methods. England: Open University Press; 2005.

- Hissong A, Lape J, Bailey D. Bailey’s Research for the Health Professional 3rd Edn. America: FA Davis Company; 2015 P95-99.

- NHS England. Building greater insight through qualitative research. Available from: bitesize-guide-qualitative-research.pdf (england.nhs.uk) [Accessed 9th July 2024]

- Flitcroft DI, He M, Jonas JB, Jong M. IMI – defining and classifying myopia: a proposed set of standards for clinical and epidemiologic studies. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2019;60(3). Available from: https://myopiainstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Defining-and-Classifying-Myopia-IMI.pdf

- Jones JB, Spaide RF, Ostrin LA, Logan NS. et al. IMI-Nonpathological Human Ocular Tissue changes with Axil Myopia. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2023;64(6). https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.64.6.5

- Jonas JB, Ohno-Matsui K, Holbach L, Panda-Jonas S. Association between axial length and horizontal length and vertical globe diameters. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017; 255(2): 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-016-3439-2

- Jones LA, Sinott LT, Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, et al. Parental history of Myopia, sports, an Outdoor Activities, and Future Myopia. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007; 48(8): 3528-3532. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.06-1118

- Bourke M, Loughman J, Flitcroft DI, Loskutova E, et al. We can’t afford to turn a blind eye to myopia, QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2023; 116(8): 635–639, https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcz076

- Xiong s, Sankaridurg P, Naduvilath T, Zang J, et al, Time spent in outdoor activities in relation to myopia prevention and control: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Ophthalmol, 2017. 95(6): p. 551-566. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13403

- Muralidharan A, Biswas C, Barathi V, Shermaine L, et al. Light and myopia: from epidemiological studies to neurobiological mechanisms. Therapeutic Advances in Ophthalmology. 2021; 13:1-45. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/25158414211059246

- Morgan I, Chang P, Ostrin LA, Willem J. IMI Risk Factors. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2021; 62(5): 3. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.62.5.3

- Mountjoy E, Daies NM, Plotnikov D, Smith GD, et al. Education and myopia: assessing the direction of causality by mendelian randomisation. bmj. 2018 Jun 6;361 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2022

- Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Hayes JR, Jones LA, et al. Accommodative Lag before and after Onset of Myopia. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2006; 47(3): 8370846. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.05-0888

- Huang PC, Hsiao YC, Tsai CY, et al. Protective behaviours of near work and time outdoors in myopia prevalence and progression in myopic children: a 2-year prospective population study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020; 104(7): 956–961. Available from: http://old.medlib.am/aknabujutyun/(2)_956.full.pdf

- Mutti DO, Jones LA, Moeschberger ML, Zadnik K. AC/A ratio, age, and refractive error in children. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2000; 41(9): 2469–2478. Available from: https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2162387

- Li S-M, Wei S, Atchison DA, et al. Annual incidences and progressions of myopia and high myopia in Chinese schoolchildren based on a 5-year cohort Study. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2022; 63:8. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.63.1.8

- Zadnik K, Sinnott LT, Cotter SA, et al. Prediction of Juvenile-onset Myopia. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2015; 133(6):683-689. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.0471

- Flitcroft DI. The comples interactions of retinal, optical, and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2012; 31: 622-660. Available from: https://adriansalgado.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/flitcroft-2012.pdf

- ABDO. Myopia management for practice teams. Available from: https://www.abdo.org.uk/regulation-and-policy/advice-and-guidelines/clinical/myopia-management-guidance-for-practice-teams/

- General Optical council. Supplementary guidance on consent. Available from: https://optical.org/media/4dibfi3g/supplementary-guidance-on-consent.pdf [Accessed 9th July 2024]

- British contact Lens Association. Myopia Management Informed Consent Form. Available from: https://www.bcla.org.uk/common/Uploaded%20files/Fact%20sheets/Children%20and%20myopia%20management/BCLA%20Consent%20form%20MM%20for%20your%20child.pdf [Accessed 9th July 2024]

- Morgan PB, McCullough SJ, Saunders KJ. Estimation of ocular axial length from optometric measures. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye. 2020;43(1): 18-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2019.11.005

- Coopervision. Axial length estimator. Available from: https://coopervision.co.uk/practitioner/tools-and-calculators/optiexpert/optiexpert-web#/axial-calculator [Accessed 9th July 2024]

- Brien Holden vision Institute. Myopia Calculator. Available from: https://bhvi.org/myopia-calculator-resources/ [Accessed 9th July 2024]

- 37Bullimore MA, Lee SS, Schmid KL, Rozema JJ, et al. IMI – Onset and Progression of Myopia in young Adults. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2023; 64(6): 2. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.64.6.2

- Bullimore MA, Brennan NA. Juvenile-onset myopia – who to treat and how to evaluate success. Eye. 2024; 38: 450-454. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41433-023-02722-6

- Caledonian Optical. Lens Catalogue 2023. Available from: https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/images.caledonianoptical.com/images/technologies/Cale-Catalogue.pdf [Accessed 9th July 2024]

- Hildenbrand GM, Ammon M. Patient perceptions of healthcare provider (un)helpful approaches to explaining health information. Communication Research Reports. 2024; 1-12 https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2024.2370778

- Hyman L, Gwiazda J, Hussein M, et al. Relationship of Age, Sex, and Ethnicity with Myopia Progression and Axial Elongation in the Correction of Myopia Evaluation Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(7):977–987. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.7.977

- Nilsen NG, Gilson SJ, Lindgren H, Kjaerland M, et al. Seasonal and Annual change in Physiological Ocular Growth of 7-11-year-old Norwegian Children. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2023; 64(10). https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.64.15.10

- Bullimore MA and Brennan NA. Myopia Control: Why Each Dioptre Matters. Optometry and Vision Science. 2019;96(6):463-465. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/optvissci/Abstract/2019/06000/Myopia_Control__Why_Each_Diopter_Matters.11.aspx