Domains and learning outcomes (C109482)

• One distance learning CPD point for optometrists and dispensing opticians

• Clinical practice

Upon completion of this CPD, ECPs will be able to describe the visible signs of thyroid eye disease (eg proptosis) and associated patient complaints (eg double vision) (s5)

Upon completion of this CPD, ECPs will be able to describe the potential psychosocial burden that thyroid eye disease may cause due to, for example, the patient’s changed appearance (s5)

Upon completion of this CPD, ECPs will be able to recognise when patients should be referred for further examination and/or treatment for suspected thyroid eye disease (s6)

The thyroid gland, located in the neck, produces and stores thyroid hormone (thyroxine). Thyroxine plays a crucial role in metabolic function, bone growth and development of the nervous system.1 Excess production of thyroxine (often due to the immune system targeting the thyroid gland) can lead to hyperthyroidism. Hyperthyroidism can cause many systemic symptoms including weight loss, heat intolerance, heart palpitations, swelling of the fingers to life-threatening thyroid crises/storm.

Thyroid eye disease (TED) also known as Graves orbitopathy, is the main extra-thyroid manifestation of Grave’s hyperthyroidism (GH) and can be present in up to 50% GH patients. TED affects up to 400,000 people in the UK.2, 3 Although more than 80% of patients with TED have a known diagnosis of GH, a smaller proportion can have other forms of thyroid dysfunction and even no thyroid problems. TED affects an estimated 10 per 10,000 of the population in Europe and is 10 times more common in women than men.4 Peak age of diagnosis is between 40-60 years.

TED is the most common cause of unilateral and bilateral forward displacement of the eyes (proptosis), which can result in significant disfigurement. It can also cause disabling double vision and can be sight threatening in 2-8% of TED patients.5

TED can impose a significant psychosocial and economic burden. A large population-based study from Denmark found TED patients are almost three times more likely to die from suicide than the healthy adult population.6 Another study from Germany looking at the socio-economic consequences found many TED patients had lost their jobs, taken early retirement or are on long term sick leave.7

Risk Factors

There are a number of risk factors that increase the risk of TED:

- Smoking significantly increases the risk of developing TED, with smokers having more severe presentations of TED.8 Patients who smoke are also known to have a poor response to immunosuppressant treatment. Smoking cessation is the greatest modifiable risk factor to developing TED.

- Poor thyroid control. Both the American and European Thyroid associations prioritise normalising thyroid function as key to TED treatment.2, 9 A high level of TSH receptor antibodies has also been associated with more severe disease course.10

- Radio-iodine treatment (RAI). Previous treatment with radioactive iodine, typically used to treat hyperthyroidism can increase the risk of TED.11 This risk is mostly mitigated by the use of systemic steroid treatment at the same time as giving RAI, as well as careful optimisation of the thyroid hormone levels after treatment.2

- Autoimmune conditions. Autoimmune conditions are diseases caused by the immune system’s cells or antibodies targeting the body’s own tissues/cells, of which GH is an example.12 TED is associated with other autoimmune conditions including rheumatoid arthritis and vitiligo.13

- Women. Like most autoimmune conditions, women are at increased risk of developing TED compared with males.14

- Hypercholesterolaemia. High levels of cholesterol, a lipid involved in cell membranes, hormone and bile production have been associated with an increased risk of TED.15

Pathophysiology

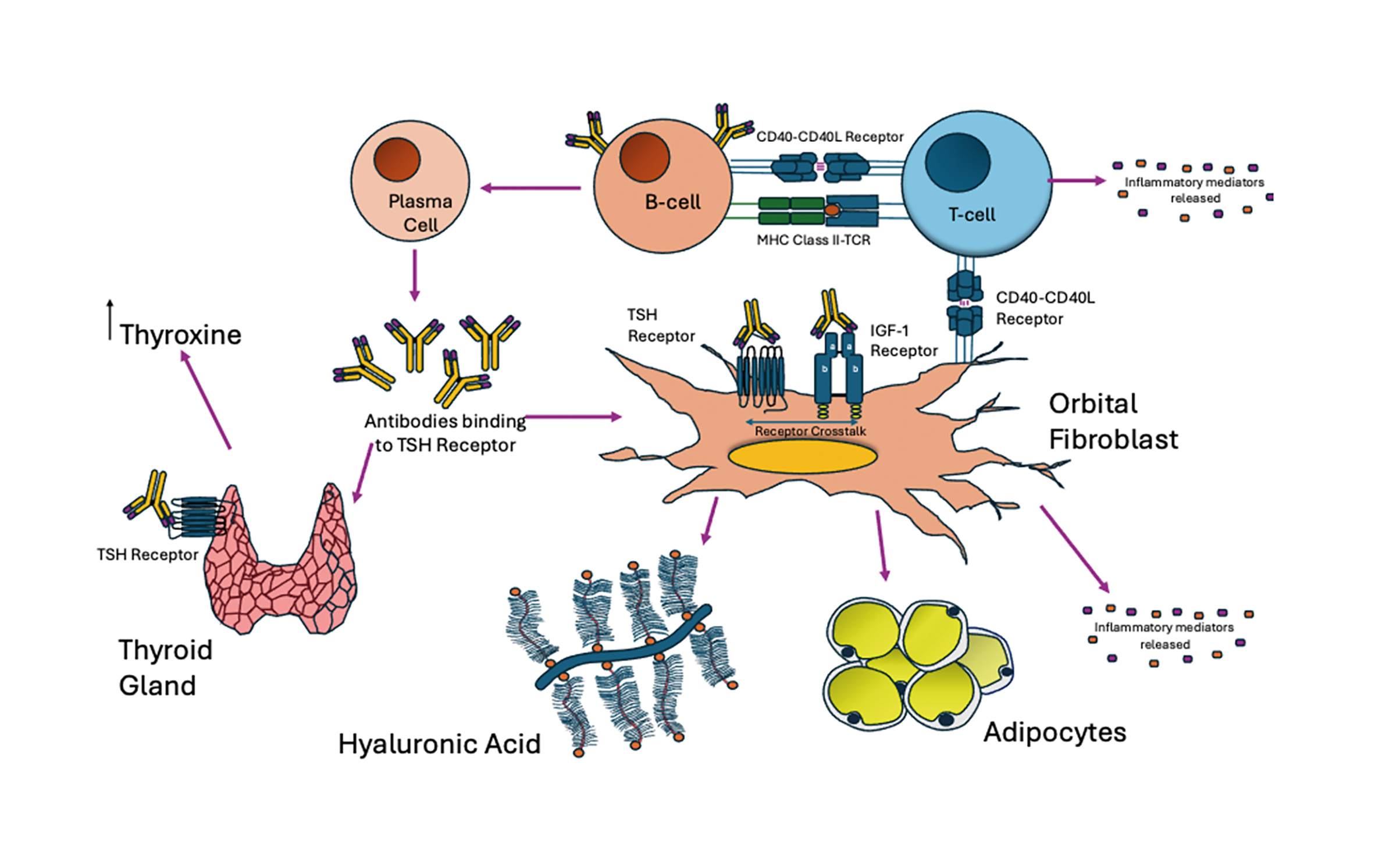

TED is an autoimmune condition where the immune system produces antibodies (using plasma cells from the support of T and B cells), which target and activate the TSH receptor to stimulate the over-production of thyroxine. These TSH receptors are also overexpressed on the retro-orbital fibroblasts in the eye socket; these are stimulated by the circulating anti bodies starting an inflammatory cascade leading to the typical appearance of TED (figure 2).

Figure 2: Pathophysiology of TED: The maturation of B cells into plasma cells using the support of T-cells via CD40/CD40L receptors and MHC Class II, allows the production of antibodies specific for the TSH-Receptor (seen in Grave’s disease). TSH receptors are expressed in the thyroid gland in the neck, which when activated by the TSH Receptor antibody, leads to the over production of thyroxine that causes Grave’s Hyperthyroidism. There is cross talk between TSH-Receptors and IGF-1 receptors found in fibroblasts (cells in the connective tissue) in the orbit at higher levels in TED. When activated by these specific antibodies can lead to increased adipogenesis (fat production) and hyaluron production causing extraocular muscle swelling. T cells and the orbital fibroblasts can interact via receptors (known as CD40/CD40L) and can drive further inflammation by releasing inflammatory mediators promoting the vicious cycle of increasing tissue volume in the confined space of the orbit leading to proptosis and double vision. Image adapted3

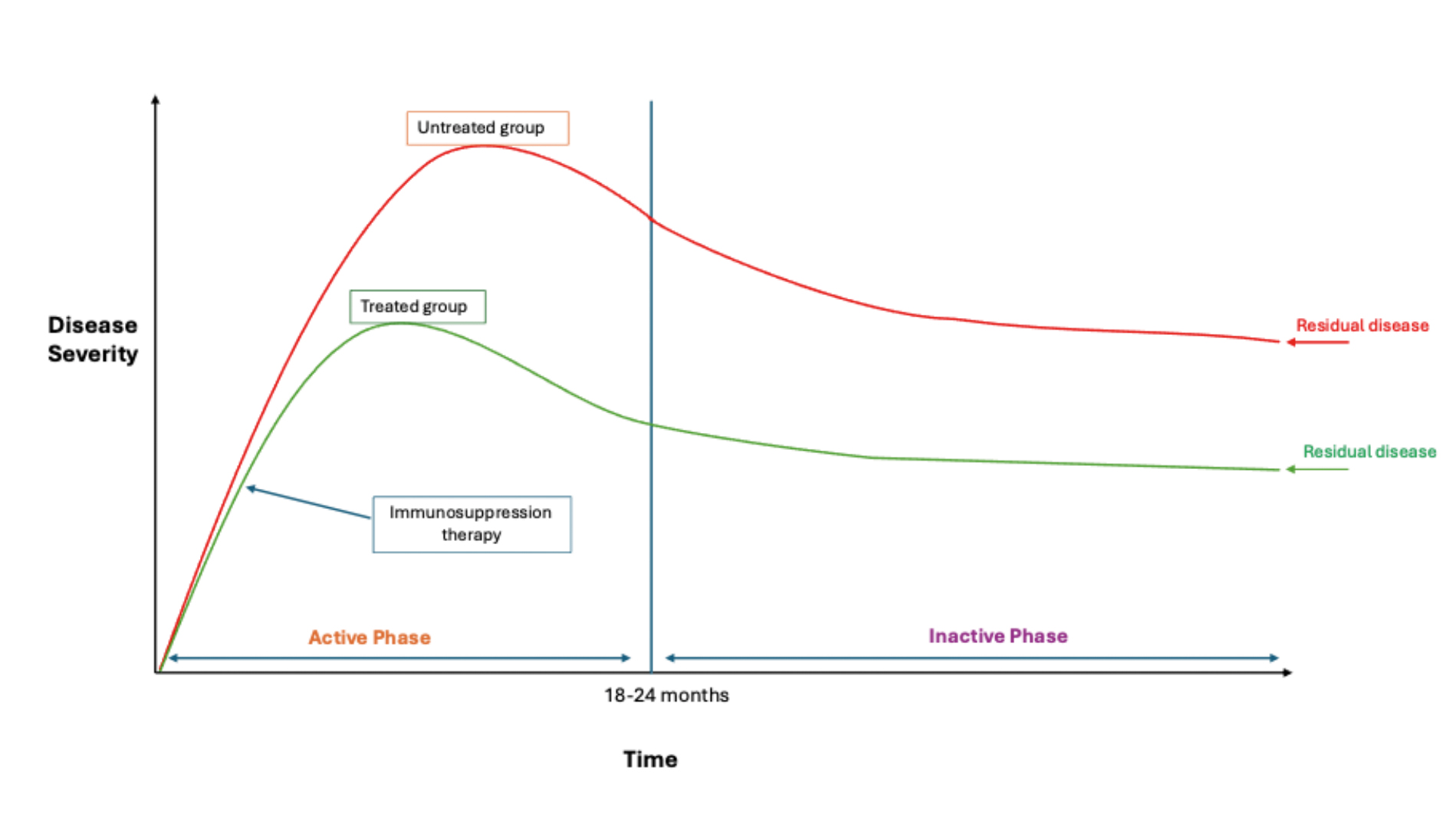

Rundle’s curve (figure 3) describes how clinical activity in TED changes over time. With the natural disease trajectory, clinical inflammatory activity will rise, stabilise and then decline, over a period of a few years. While disease activity will eventually reduce, the patient is often left with residual disease if there was significant disease severity. If immunosuppressive treatment (eg steroids) is provided at an early stage during active disease phase, this will hopefully reduce the level of residual disease in the long term. Therefore, immunosuppressive treatment is more effective when started early during the active phase on Rundle’s curve.3

Figure 3: Rundle’s Curve. Graph showing the natural history (untreated group, red curve) of Thyroid eye disease of disease activity against time. Initially, TED enters an active phase where disease activity is at its highest, which normally resolves by two years; patients will be left with residual disease in the inactive phase. Treatment has initially predicated on initiating immunosuppressant therapy at an early stage which can reduce the level of residual disease as shown in the treated group (green). Note that residual disease whether treated or untreated will never return back to the normal baseline.

Case Study 1:

Case Study 1:

Maya, a 58-year-old Afro-Caribbean nurse, presented to her optician in the early summer (May) with watering eyes. Initially believing her symptoms were related to seasonal allergy, she took fexofenadine, bought over the counter, with no improvement. At this stage she had no double vision. She recently had a Covid-19 infection but was otherwise fit and well and not taking medication.

On examination, the only abnormal feature was slightly raised intra-ocular pressures of 22mmHg, but no other signs of glaucoma. She was advised to seek an ophthalmology referral.

A month later, Maya developed swelling in her right eye. Her GP referred her to a maxillofacial surgeon who arranged an MRI and ultrasound scan of her face. This doctor diagnosed eyelid infection, and she was given antibiotic and steroid ointment; however her symptoms did not improve. She was then reviewed by an ophthalmologist who reassured that there were no signs of glaucoma, but advised she be seen by an oculoplastic surgeon for the eyelid swelling. In the meantime, her GP prescribed oral antibiotics, which improved the swelling. Given her clinical improvement, she cancelled her upcoming appointment with the oculoplastic surgeon.

Another month later (July), she developed severe headaches affecting the whole of her head. She was seen by a neurologist who performed an urgent brain MRI, which was reported as normal. The neurologist then referred Maya to a rheumatologist to investigate for an underlying systemic inflammation, eg sarcoidosis.

In August, she developed severe pain in her left eye with persistent double vision making it difficult to focus. She consulted an oculoplastic surgeon/thyroid eye specialist who diagnosed her with thyroid eye disease (TED). Thyroid blood tests confirmed Maya had an overactive thyroid alongside elevated thyroid receptor antibodies. She was referred to an endocrinologist who diagnosed Graves hyperthyroidism and started Maya on anti-thyrotoxicosis treatment.

Due to her severe active TED, Maya commenced immunosuppressant therapy (steroid therapy in the form of intravenous methylprednisolone, and oral immunosuppressant mycophenolate mofetil). Maya completed a 12-week course of intravenous steroids, but had minimal clinical improvement regarding pain, swelling and double vision. She remained under regular follow up at the multidisciplinary thyroid eye clinic during the treatment.

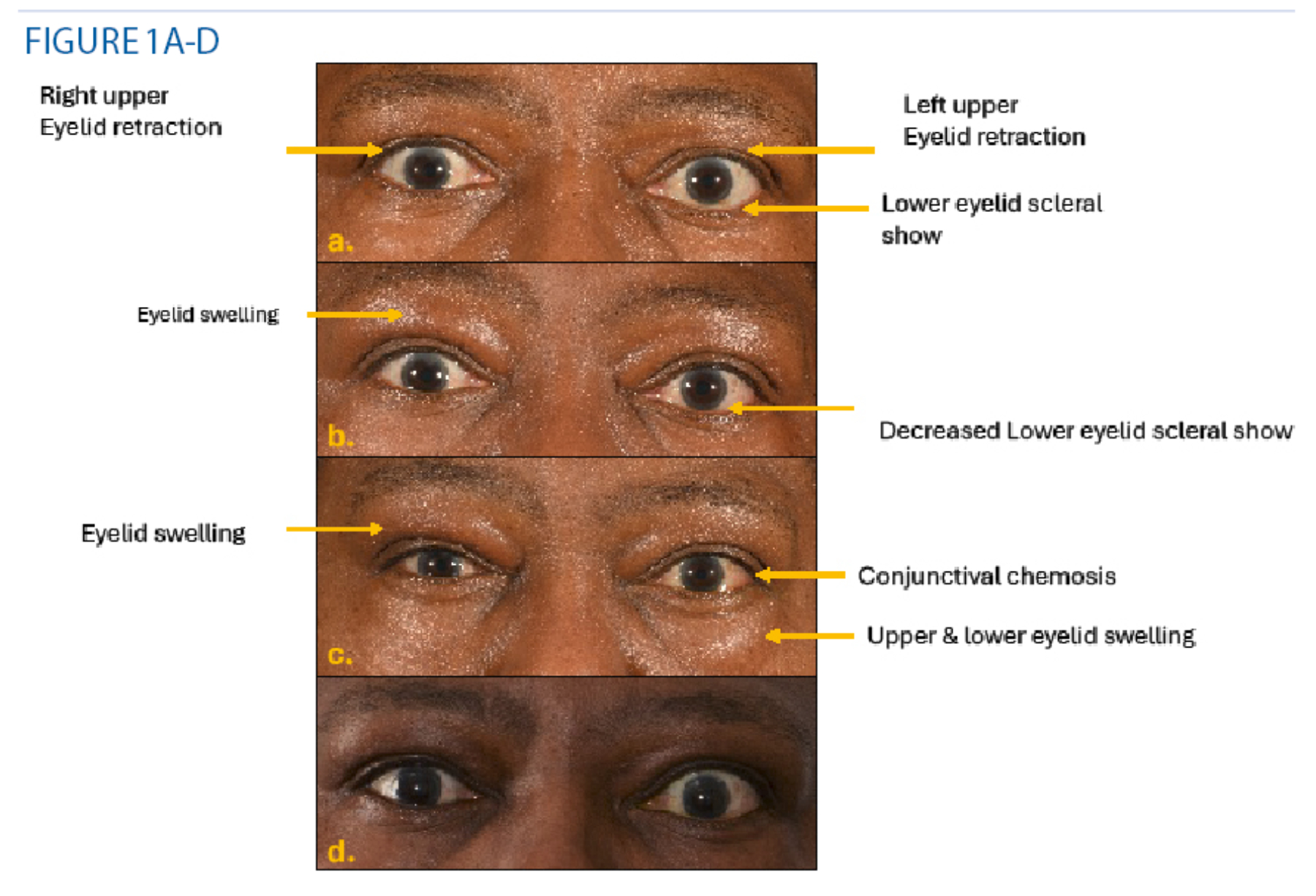

Two weeks following the completion of her steroid course in November, Maya’s vision deteriorated in her left eye, and she was diagnosed with sight-threatening TED (figure 1A) Her CAS score was 3 (pain at rest (1), pain on eye movements (1), deterioration in vision (1). She underwent urgent left orbital decompression surgery with immediate improvement in her left vision and ocular pain.

However, in the following weeks she develops new painful swelling in her right eye (alongside her left); she continued to have disabling double vision. About two months after stopping the intravenous steroids and being maintained only on oral mycophenolate the TED was flaring up in both orbits. The right orbit was also becoming more inflamed whereas previously it was mainly the left orbital involvement.

Figure 1b demonstrates the development of bilateral features. Her CAS score was 4 with bilateral pain at rest (1), with eye movements (1), swelling (1) and redness (1) of eyelids). However, the left proptosis has decreased with a decreased lower eyelid scleral show after the orbital decompression surgery.

The thyroid eye specialist in the MDT clinic recommended 10 cycles of orbital radiotherapy to control her TED.

Following radiotherapy, she experienced an initial significant improvement in the movement of her eye muscles with less double vision and without pain.

Unfortunately, a month following radiotherapy, her TED inflammation flared again (figure 1c), with recurrence of swelling around eyelids bilaterally with a CAS score of 5 pain at rest (1)and with eye movements(1) swelling (1) and redness (1) of eyelids, left conjunctival chemosis (1).

She was then given orbital steroid injections, since she had exceeded the maximum safe dose of intravenous steroids. She was advised to undergo thyroidectomy (removal of her thyroid gland) to control her eye disease.

Despite an uneventful thyroidectomy, her TED inflammation persisted, so Maya was started on a new biological therapy Tocilizumab. Fortunately, Tocilizumab has improved her pain, double vision and her appearance (figure 1d). At her last visit, she had a CAS score of 1 (eyelid swelling) with minimal double vision. Maya could continue working as a nurse. She remains on oral mycophenolate treatment and close follow up in the thyroid eye clinic.

Case study: Maya 2

Unfortunately, Maya saw a number of medical specialists who did not consider TED as a diagnosis. As a result, her treatment was significantly delayed, allowing the disease activity and severity to progress to such a severe extent that it was difficult to control, even when appropriate treatment was started.

Clinical Features

Symptoms of TED can mimic dry eye disease with conjunctival redness, epiphora and grittiness. Ocular surface inflammation is commonly found in TED.16 More severe symptoms include proptosis, pain around the eyes and eye misalignment (strabismus) are caused by the underlying orbital inflammation.

Proptosis occurs when there is intra-orbital volume expansion secondary to the increased size of the extra ocular muscles, fat or both. This can be extremely disfiguring and disabling. Visual loss can occur due to exposure keratopathy (eyelid retraction cause drying of the exposed cornea) or compressive optic neuropathy (due to the intra-orbital volume expansion compressing on the optic nerve at the back of the eye).

Clinical Assessment

When screening patients for TED, the Vancouver Orbital Rule (VOR) is a useful screening tool to perform:17

- Swelling or feeling of fullness in one or both of upper eyes?

- Bags under eyes?

- Redness in eyes or eyelids?

- Do your eyes seem to be too wide open?

- Is your vision blurry (even with glasses/contacts)?

If yes to Q1 or Q2 and yes to any of Q3 to Q5? →Refer patient to a TED specialist clinic.

When assessing a patient suspected of TED, visual acuity, visual fields and colour vision should be performed (which can assess for progression of sight threatening disease affecting the optic nerve). Ocular motility assessment quantified using Hess charts, field of binocular single vision and uniocular ductions should be performed to assess double vision and movement for each eye.

Clinical activity score (CAS)

In TED, CAS scores for three key aspects of inflammation (one point for each area eg redness in both the eyelids and conjunctiva would score two points):

Clinical Activity Score (CAS)18

Add 1 point for each finding:

- Symptoms

- Pain or pressure in a periorbital or retroorbital distribution

- Pain with upward, downward or lateral eye movement

- Signs

- Swelling of the eyelids

- Redness of the eyelids

- Conjunctival injection

- Chemosis

- Inflammation of the caruncle or plica

- Changes

- Increase in measured proptosis > 2mm over one to three months

- Decrease in eye movement limit of > 8º over one to three months

- Decrease in visual acuity (two Snellen chart lines) over one to three months

A CAS of three or more would suggest active TED.2

Case study: Maya 3

Maya’s initial Cas score Yes to Q1-3. Notably, CAS does not consider proptosis, ocular motility disturbance or optic nerve compromise at the first visit, and therefore should not be relied upon as the only assessment tool.3 Moreover, as the scoring was developed in a white population in the Netherlands CAS can be less reliable for patients from other ethnic groups.

Radiology

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best imaging modality to assess patients with TED, due to its superior resolution of soft tissues5 and can also help assess the activity and the fat: muscle contribution to the proptosis as well as excluding other possible causes like orbital tumours.

Quality of life (QoL)

Given the significant psychosocial burden, the GOQOL is a widely adopted and validated TED QoL outcome measure tool to assess the visual and psychosocial impact of the patient’s changed appearance19 and to assess the efficacy of treatment.

Management

The ideal treatment would restore visual function, diplopia, proptosis and visual disfigurement with an optimal safety profile. The Thyroid Eye disease Amsterdam Declaration Implementation group (TEAMeD-5) was created to improve awareness of TED, and facilitate referral to specialists including ophthalmologists, endocrinologists for early treatment, based on recommendations from the European Group on Graves Orbitopathy (EUGOGO).5

When treating TED, two clinical questions should be initially asked:

- What is the severity of the illness – mild, moderate to severe or sight threatening? (Based on EUGOGO classification)

- Is the disease active or inactive?

Mild disease: Typically features will have a minor impact on QoL

Treatment usually focuses on controlling risk factors for disease:

- Smoking cessation20

- Selenium supplementation20

- Controlling thyroid dysregulation5

- Thyroid dysregulation can be controlled with anti-thyroid medication, radioactive iodine or surgery to remove the thyroid (total thyroidectomy).2

- Anti-thyroid medication – usually employs carbimazole first line or propylthiouracil. Alternatively, ‘block and replace’ treatment can be used where a constantly higher dose of anti-thyroid medication can be used over a short time duration, alongside thyroxine supplementation which can avoid an underactive or overactive thyroid levels (although has compliance issues and is contraindicated in pregnancy).21

Local treatments including maximising dry eye treatment.2

Often with mild disease, there will be spontaneous resolution of symptoms – usually watchful waiting, optimising risk factors and local treatments is usually sufficient. However, if the patient reports a severe impact on their QoL then low dose immunomodulation may be considered in active disease, or rehabilitative surgery for inactive disease.2

Moderate to severe: Significant impact on QoL

Active disease: During the initial active phase, while optimising risk factors (as for mild TED), immunosuppressant therapy is used to reduce the disease activity, ideally offered within six weeks from presentation.20

First line treatment consists of intravenous methylprednisolone (steroid therapy) infusion over 12 weeks, with mycophenolate (an additional immunosuppressant agent).2 Intravenous therapy is often better tolerated than oral corticosteroids. Studies have shown all patients with methylprednisolone have a reduction in their CAS score compared to only 33% of placebo.3

Second line treatment includes oral prednisolone, orbital radiotherapy and other immunomodulating drugs such as Azathioprine, Cyclosporine and biological therapy including Tocilizumab and Teprotumumab.3

Inactive disease: Once inactive, patients can be considered for rehabilitation surgery. This involves multiple procedures performed on separate days: initially orbital decompression (to treat the proptosis), followed by intraocular muscle surgery and eyelid surgery to correct the diplopia and disfigurement.3 This is performed once the disease is inactive, as suboptimal outcomes will occur if patients relapse following surgery.

Sight threatening: This is an emergency scenario. Sight threatening TED would include features suggestive of optic neuropathy, corneal exposure, and eyeball displacement. Sight threatening TED should be treated initially with several single high doses of intravenous methylprednisolone over three consecutive days with daily clinical examinations. If a satisfactory response is made to steroid therapy, this is subsequently repeated and slowly tapered down.2

If response is partial or absent to steroid therapy, then the patient is referred for urgent orbital decompression surgery. Notably, severe corneal exposure or eye displacement should also be referred for urgent orbital decompression surgery.2

Traditionally, management of TED has predicated on providing immunosuppression at an early stage during the ‘active’ phase in patients with moderate to severe or sight threatening disease to reduce the long-term residual disease burden (see Rundle’s curve).

Immunosuppressive treatment should improve double vision, swelling and visual loss, but will not reverse the proptosis. The proptosis and eyelid retraction can usually only be improved by rehabilitation surgery when TED activity is inactive, and the thyroid is controlled. This means as most patients who are started on medication for 18 months to two years will have to wait for that time before surgery can be safely undertaken due to the risk of hyperthyroidism in 50% patients after stopping anti-thyroid medication, which can lead to a reactivation of TED.

Case study: Maya 5

Maya was initially diagnosed as active moderate-severe category of TED given her constant double vision and the marked impact on her QoL. Given the severity, she was treated with a course of intravenous methyl prednisolone, but the inflammation was so severe that this did not resolve all her symptoms.

Unfortunately, once she stopped the steroids her TED flared, and she developed sight threatening TED. This required urgent orbital decompression surgery that initially improved her vision and provided a chance for the second line immunosuppression treatment (mycophenolate) to take effect. Orbital radiotherapy was another second line treatment given to try to control her TED. As her inflammation was still active, she was started on third line biological therapy with Tocilizumab, and her TED finally became quiescent.

There is debate how much thyroidectomy helps in the control of severe TED, highlighting the need for multidisciplinary expertise to guide management.

Biological Therapy – changing the paradigm

New drugs over the past two decades have been developed which can prime the immune system targeting cell receptors or proteins in the body. These biological therapies consist of therapeutic antibodies that target a specific part of the immune system minimising side effects and are widely used in other systemic inflammatory conditions.

Rituximab, a drug first developed for haematological cancers, targets antigens found on B-cells which can suppress inflammation in TED, while Tocilizumab is widely used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. These biological therapies can be effective second line agents in treating TED and has benefitted Maya.

However, neither Rituximab or Tocilizumab are licensed for use in TED, so these drugs are used ‘off label’, and often require special funding requests to be used in the NHS.

Teprotumumab targeting the IGF-1 receptor has shown to address both the inflammation and disfigurement in TED and is approved for TED in the USA.22 Notably, Teprotumumab also appears to be effective in chronic TED, providing new evidence to contradict Rundle’s curve that residual disease once inactivated, would not respond to medical therapy. Teprotumumab is not currently available in the UK, costly and carries uncertainty regarding the longevity of the therapeutic response.

Side effects of Teprotumumab can include hearing loss and hyperglycaemia. Nevertheless, it has created a paradigm shift in TED therapy that has promoted the development of many novel drugs targeting the same receptor as Teprotumumab, as well as other aspects of the TED inflammatory pathway.3

Conclusion

TED is a complex and debilitating condition, and its irreversible disfigurement can have a significant impact psychosocial wellbeing. In the primary care setting, there should be a low threshold to implement appropriate screening tools including the VOR and CAS to identify patients at initial stages to facilitate early referral to multidisciplinary specialist clinics where both the TED and the thyroid dysfunction can be optimally managed.

To improve awareness of TED, TEAMeD-5 consortium published five key recommendations:5, 20

- 1. Diagnose – Identify patients with Graves’ disease, checking for antibodies targeting the TSH-Receptor.

- 2. Screen – Grave’s disease patients for TED.

- 3. Alert – Patients with Graves’ disease of the risk of developing TED

Improves education and management.

Provide an early warning card (available at specialist clinics)

- 4. Prevent – Risk factor modification

- Smoking cessation.

- Correct thyroid dysregulation.

- 5. Refer to specialist clinic with multidisciplinary input

- Timely referrals to MDT clinics with specialists including ophthalmologists, endocrinologists, and radiologists.

- Early referral to specialist centres leads to improved control of symptoms, with combined expertise to improve time to diagnosis and treatment.

- BOPSS (British Oculoplastic Surgery Society) national directory available to identify your local specialist service for TED referrals: www.bopss.co.uk/ted-directory.

Case study: Maya 6

Maya’s symptoms from acute TED included dry eyes, proptosis, eyelid swelling, and restriction of eye movements causing severe double vision, as well as sight threatening compression of her left optic nerve. She finally responded after all the available conventional treatment – intravenous methylprednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil, orbital radiotherapy and tocilizumab. She also had urgent left orbital decompression. When her inflammation and disease activity have settled off all immunosuppression, if she remains unhappy, with the disfigurement or has residual severe double vision she may be suitable for rehabilitation surgery.

- Miss Vickie Lee specialises in treatment of all orbital, lacrimal and eyelid conditions. She is a leading specialist in orbital trauma and thyroid eye disease. She is the British Oculoplastic Surgery Society’s National Lead for Thyroid Eye Disease (TED) and authored the national guidelines for TED and led the compilation of a national directory for thyroid eye services. She leads multidisciplinary TED services across three NHS hospitals for TED that are internationally recognised.

- Dr Kitt Dokal is a junior doctor working in London. He recently completed a specialised foundation programme in infectious diseases at Imperial College London and has a keen interest in medical ophthalmology.

Declarations of interest

Vickie Lee is the British Oculoplastic Surgery Society National Lead for Thyroid Eye disease and is the Principal Investigator for studies by Horizon Viridian Sling and Lassen. She has received honoraria for consultations and served on advisory boards for Horizon Amgen and Viridian.

References

- Pirahanchi Y, Tariq MA, Jialal I. Physiology, Thyroid. StatPearls [Internet]. 2023 Feb 13 [cited 2024 Aug 2]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519566/

- Bartalena L, Kahaly GJ, Baldeschi L, Dayan CM, Eckstein A, Marcocci C, et al. The 2021 European Group on Graves’ orbitopathy (EUGOGO) clinical practice guidelines for the medical management of Graves’ orbitopathy. Eur J Endocrinol [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Aug 2];185(4):G43–67. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.1530/EJE-21-0479

- Moledina M, Damato EM, Lee V. The changing landscape of thyroid eye disease: current clinical advances and future outlook. Eye [Internet]. 2024 Jun 1 [cited 2024 Aug 2];38(8):1425. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC11126416/

- Lazarus JH. Epidemiology of Graves’ orbitopathy (GO) and relationship with thyroid disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab [Internet]. 2012 Jun [cited 2024 Aug 2];26(3):273–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22632364/

- Farag S, Feeney C, Lee V, Nagendran S, Jain R, Aziz A, et al. A ‘Real Life’ Service Evaluation Model for Multidisciplinary Thyroid Eye Services. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) [Internet]. 2021 May 7 [cited 2024 Aug 2];12:669871. Available from: www.frontiersin.org

- Ferløv-Schwensen C, Brix TH, Hegedüs L. Death by Suicide in Graves’ Disease and Graves’ Orbitopathy: A Nationwide Danish Register Study. Thyroid [Internet]. 2017 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Aug 2];27(12):1475–80. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29084476/

- Ponto KA, Pitz S, Pfeiffer N, Hommel G, Weber MM, Kahaly GJ. Quality of Life and Occupational Disability in Endocrine Orbitopathy. Dtsch Arztebl Int [Internet]. 2009 Apr 24 [cited 2024 Aug 2];106(17):283. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2689575/

- Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM. Smoking and Risk of Graves’ Disease. JAMA [Internet]. 1993 Jan 27 [cited 2024 Aug 5];269(4):479–82. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/403015

- Burch HB, Perros P, Bednarczuk T, Cooper DS, Dolman PJ, Leung AM, et al. Management of Thyroid Eye Disease: A Consensus Statement by the American Thyroid Association and the European Thyroid Association. Thyroid [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Aug 6];32(12):1439–70. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2022.0251

- Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM, Mourits MP, Koornneef L, Berghout A, Van Der Gaag R. Effect of Abnormal Thyroid Function on the Severity of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Arch Intern Med [Internet]. 1990 May 1 [cited 2024 Aug 5];150(5):1098–101. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/613355

- Träisk F, Tallstedt L, Abraham-Nordling M, Andersson T, Berg G, Calissendorff J, et al. Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy after Treatment for Graves’ Hyperthyroidism with Antithyroid Drugs or Iodine-131. J Clin Endocrinol Metab [Internet]. 2009 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Aug 6];94(10):3700–7. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-0747

- Perros P, Hegedüs L, Bartalena L, Marcocci C, Kahaly GJ, Baldeschi L, et al. Graves’ orbitopathy as a rare disease in Europe: a European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy (EUGOGO) position statement. Orphanet J Rare Dis [Internet]. 2017 Apr 20 [cited 2024 Aug 6];12(1):1–6. Available from: https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-017-0625-1

- Kelada M, Avari P, Farag S, Akishar R, Jain R, Aziz A, et al. Association of Other Autoimmune Diseases With Thyroid Eye Disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) [Internet]. 2021 Mar 5 [cited 2024 Aug 2];12. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33746907/

- Bartalena L, Piantanida E, Gallo D, Lai A, Tanda ML. Epidemiology, Natural History, Risk Factors, and Prevention of Graves’ Orbitopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) [Internet]. 2020 Nov 30 [cited 2024 Aug 6];11. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7734282/

- Sabini E, Mazzi B, Profilo MA, Mautone T, Casini G, Rocchi R, et al. High Serum Cholesterol Is a Novel Risk Factor for Graves’ Orbitopathy: Results of a Cross-Sectional Study. Thyroid [Internet]. 2018 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Aug 6];28(3):386–94. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29336220/

- Liao X, Lai KKH, Aljufairi FMAA, Chen W, Hu Z, Wong HYM, et al. Ocular Surface Changes in Treatment-Naive Thyroid Eye Disease. J Clin Med [Internet]. 2023 May 1 [cited 2024 Aug 10];12(9). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37176507/

- Mohaseb K, Linder M, Dolman P, Wilkins GE, Rootman J. Validation of a Screening Rule for Thyroid Orbitopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003 May 1;44(13):768–768.

- Mourits MP, Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM, Koornneef L. Clinical activity score as a guide in the management of patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) [Internet]. 1997 [cited 2024 Aug 6];47(1):9–14. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9302365/

- Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Mourits MP, Gerding MN, Baldeschi L, Kalmann R, et al. Interpretation and validity of changes in scores on the Graves’ ophthalmopathy quality of life questionnaire (GO-QOL) after different treatments. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2024 Aug 2];54(3):391–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11298093/

- Lee V, Avari P, Williams B, Perros P, Dayan C. A survey of current practices by the British Oculoplastic Surgery Society (BOPSS) and recommendations for delivering a sustainable multidisciplinary approach to thyroid eye disease in the United Kingdom. Eye [Internet]. 2020 Sep 1 [cited 2024 Aug 2];34(9):1662. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7608203/

- Bartalena L. Treatment of hyperthyroidism: block and replace versus titration. Endocr Abstr. 2008;16(S1.1).

- Kossler AL, Douglas R, Dosiou C. Teprotumumab and the Evolving Therapeutic Landscape in Thyroid Eye Disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab [Internet]. 2022 Sep 1 [cited 2024 Aug 2];107(Suppl 1):S36. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9359446/