Domains and learning outcomes (C109529)

One distance learning CPD point for optometrists and dispensing opticians.

• Communication

(s.2.1) After successful completion of this CPD practitioners will be able to discuss the differing facial characteristics, plagiocephaly and dispensing challenges associated with Cerebral palsy and Down’s syndrome adapting language and communication approach accordingly.

• Clinical practice

(s.5.3) After successful completion of this CPD practitioners will recognise how Cerebral palsy and Down’s syndrome impact visual and facial development and the appropriate spectacle frame adaptions that can be applied to improve fitting.

The challenges faced with paediatric dispensing are well known. Requiring confidence, endless patience and expert communication skills, the dispensing optician must manage the needs and expectations of both the child and the parent/carer while trying to achieve the best fit possible.

However, the dispense can be further complicated when a patient has a condition or syndrome which means a good fit cannot be achieved with a standard pair of glasses. This could be due to head and facial measurements that differ from the age-related norms, dysmorphic features or because of other lifestyle factors that affect the use of the glasses.

Part one of this series (Optician 19.04.24) looked at paediatric dispensing for children with craniosynostosis and congenital cataract. In this second article, we will consider two further paediatric conditions, which may affect the frame and lens choice, required measurements, and the way the patient uses their glasses. For each condition, the pathology and ophthalmic management will also be discussed.

Cerebral Palsy

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a term used to describe a group of non-progressive neurological disorders that begin in infancy or early in childhood and affect movement, muscle coordination, balance, and posture. CP is caused by damage or an abnormality within the developing brain. Damage can be caused by a lack of oxygen, intracranial haemorrhage, infections, toxicity or trauma. The level of disability can vary from slight to profound.

The effect on the eyes

There are numerous visual deficits associated with CP:

- Emmetropisation is often impaired in children with CP and consequently such children are more likely to have a refractive error.1 Research has shown that between 28.5% and 54% of patients with CP will have a refractive error.

- Around 50% of children with CP have reduced accommodation2 and therefore require near spectacle correction as well as the correction of any refractive error.

- Around 33-50% of patients with CP will have strabismus.3

- Nystagmus occurs in approximately 1% to 18% of cases.3

- Ptosis occurs in approximately 1 to 2.5% of cases.3

- Between 60 and 70% of children with CP will have cortical visual impairment (CVI).4 CVI is when there are visual problems caused by the brain and its ability to interpret the visual information rather than any ocular findings.

Damage to any areas of the brain where the higher visual processing takes place can cause problems such as:

- Reduced visual fields, visual acuity and contrast sensitivity.

- Abnormal ocular movements and fixation.

- Inability to recognise faces and facial expressions.

- Inability to recognise shapes.

- Orientation difficulties.

- Difficulties with busy visual scenes.

- Difficulty controlling and moving limbs due to poor visual guidance/spatial processing.

There is currently no cure for CVI, however there are a number of strategies that caregivers can implement in order to tailor the child’s environment to make visual processing and everyday life easier. Many of these strategies are useful when thinking about how we approach dispensing for a child with CVI. For example, a patient with CVI may have impaired attention and difficulty multitasking so we should aim to keep distractions to a minimum and avoid overwhelming them.

It may be helpful to only present one or two frames at a time and to book a dispensing appointment when clinic is quieter with fewer distractions. If a patient has hemianopia, always present glasses from the side they can see and try not to make the patient jump with sudden movement on the side of the restricted fields. Once the patient has collected the glasses, it might help to have a specific place where only the glasses are kept making it easier for the patient to find them.

Dispensing considerations

Some patients that have weakness in the neck muscles cannot hold their head up for a sustained period and may have wheelchair mounted head rests to keep the head in the desired position. This can impact the way the patient wears their glasses. Depending on the position of the headrest, a wide frame or a frame with long temples is unlikely to work. While supporting the patient’s head, the headrest is likely to push on the glasses, altering the position, making the frame uncomfortable and limiting the patient’s vision.

Instead, the frame should be kept as neat as possible with small lugs. Curl sides may provide more stability and support and fit snuggly around the patient’s ear to limit movement. A silicone covering on the curl sides will be more comfortable and supportive. The curl sides should not extend beyond the ear lobe and the inward angle should match that of the patient’s head. The wheelchair in which the patient has attended the appointment might not necessarily be the wheelchair the patient uses on a day-to-day basis.

If this is the case, check what the everyday wheelchair is like and where the headrests are situated. If a patient spends a lot of time leaning on one side of their head, a thick plastic side may be uncomfortable. The Nanovista frame with a strap attached to the front might be a better option (see figure 1).

Figure 1: A Nanovista frame with a strap attached to the front

Movement – a patient with CP may have unintentional movements that vary depending on the type of CP the patient has. They may be small random muscle movements or larger head and body movements that are sustained, intermittent, irregular or abrupt. The glasses need to stay in the correct position despite these movements.

Nystagmus – A patient may adopt a certain head position utilising the null point in order to reduce the nystagmus and improve their vision. If you notice a patient has nystagmus, check if they have a null point and ensure the glasses are not obstructing this. A frame may need to be chosen that has a shape which allows more vision in the direction of their null point. A large, round aperture may give the best vision.

Helmets – A helmet may be worn to prevent injury if the child falls if they suffer from seizures or if they exhibit challenging behaviours such as headbanging. Ask the parent/carer to bring the helmet with them to the dispensing appointment and check that the frame can be worn comfortably with the helmet.

Strength of the frame – A patient with CP may be heavy handed with their glasses due to limited hand-eye coordination and movement. The frame needs to be able to withstand this lifestyle without needing constant repairs. For older children who still need a strong and flexible frame but require adult sized dimension, the Centrostyle Leisure Time frames are available up to a 53 eye size.

Epilepsy – This is common in patients with CP and so the glasses must be made as safe as possible in case of a seizure. Ideally the frame will have a metal free construction and be made from a strong, flexible material. Lenses should be polycarbonate or trivex with no sharp edges, particularly on high minus lenses. If a high minus prescription is required, keep the edge thickness to a minimum by avoiding decentration and ask for a heavy safety chamfer from the lab. Blended lenticular lenses may be a safer option.

Reduced visual fields – Ensure the frame shape is not limiting the unaffected area of vision. For patients with peripheral vision only, a large round aperture may work well.

Bifocals or single vision lenses – For patients who have good eye movement control, bifocals may work well. For those that do not, looking through the correct portion of the lens may be difficult, and two separate pairs of glasses may be the better option. If two separate pairs are used, dispense two different frames, and ensure that the school know which pair is for distance and which is for reading.

Ptosis – A patient may adapt a chin up posture in order to see the upper visual field. Ensure there is enough depth at the bottom of the frame and set the vertical optical centres lower to account for this.

Eyegaze technology – Patients with CP may use Eyegaze technology. The technology tracks a patient’s eye movements enabling them to move the mouse and communicate. An antireflective coating on the lenses may help the technology to track the eye movements.

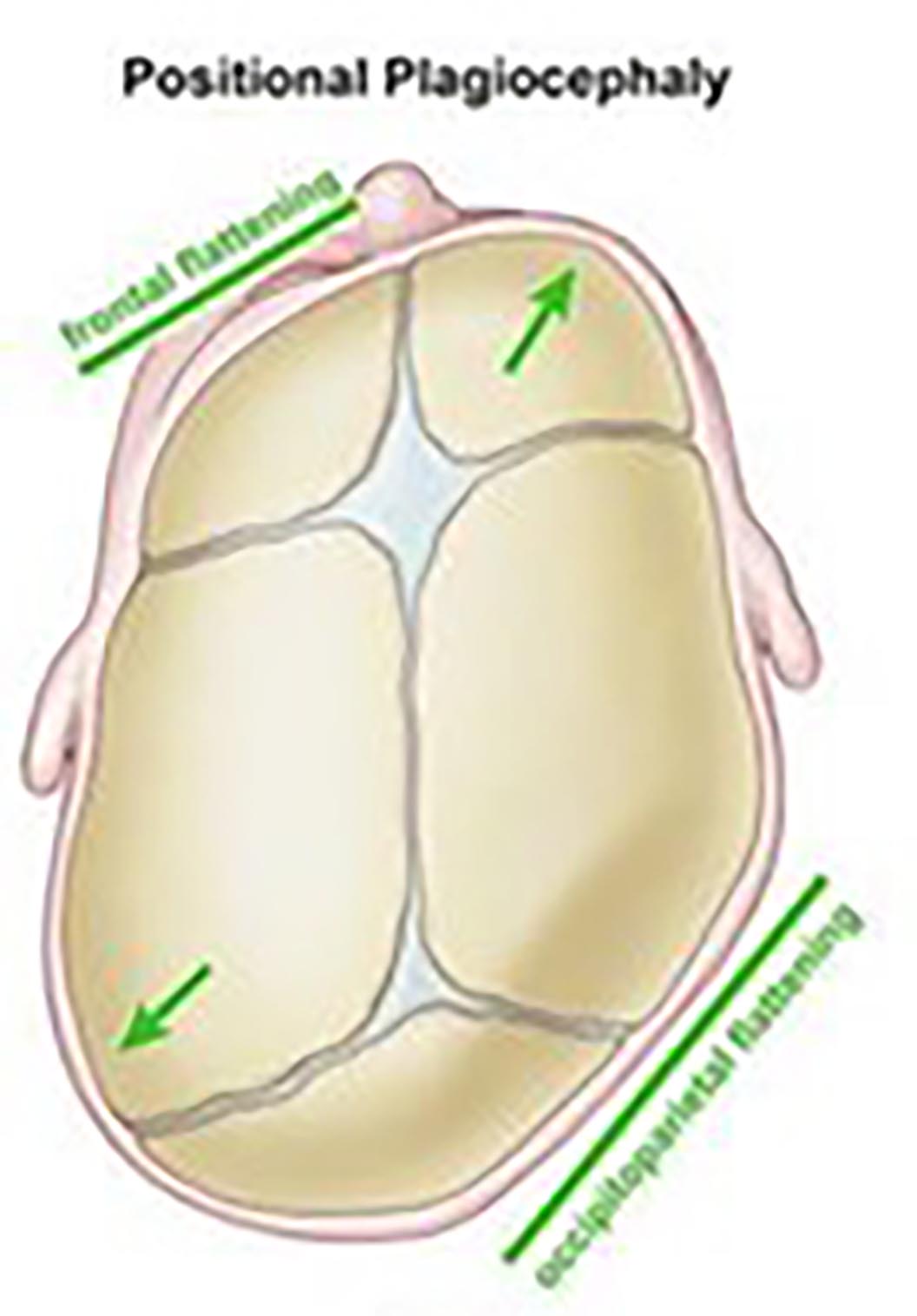

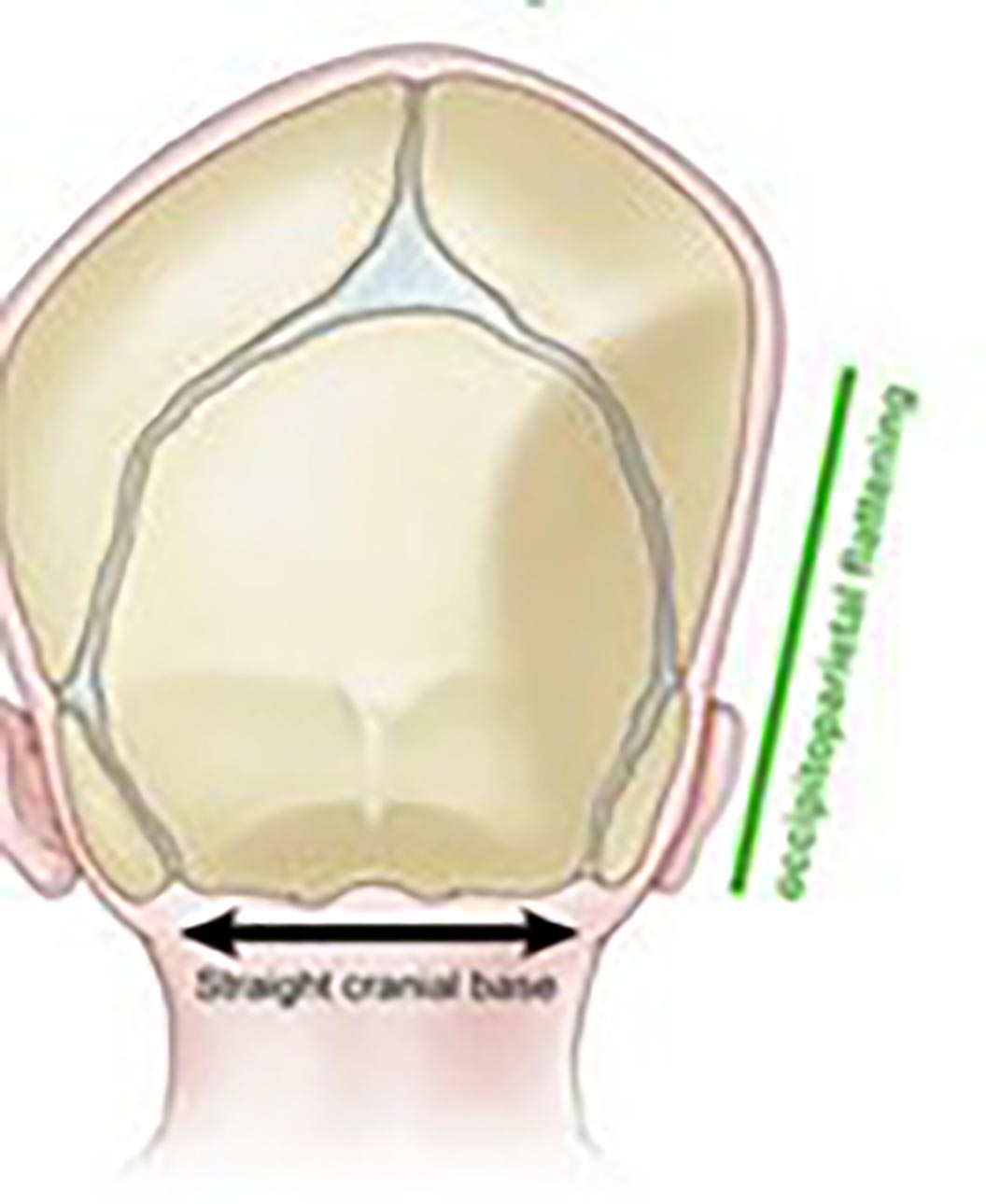

Figure 2: Plagiocephaly

Asymmetrical skull deformity (ASD) or plagiocephaly – This is often seen in children with severe cerebral palsy. It is thought this is due to one sided facial direction development during infancy when the skull is soft (see figure 2). Once ASD has started to develop it can cause an asymmetric posture and more pressure on the flattened side.5 Depending on the location of the plagiocephaly on the skull, plagiocephaly may require glasses that have asymmetric side lengths and lengths to bends, different inward angles of drop and uneven angles of let-back to account for unequal back vertex distances. Dispensing glasses that are easily adjustable is vital.

Figure 3 shows a boy with CP, CVI and aphakia wearing a Centrostyle frame. The large aperture has maximised his field of view, but still maintained good centration and reduced lens thickness at the nasal edges. In order to limit the movement of the glasses, the Centrostyle frame was fitted with soft curl sides.

The patient also uses Eyegaze technology and so a MAR coating was dispensed.

Figure 3: A young boy with CP and CVI wearing a Centrostyle frame fitted with curl sides. The lenses are 1.6 index, 38mm bowl lenticular lenses with a MAR from Optimum Coatings

Down’s Syndrome

Down’s syndrome is one of the most common genetic conditions in the world, with a prevalence of approximately one in 700 live births.6 There are three different forms of Down’s syndrome:

- Trisomy 21 is the most common form of Down’s syndrome, occurring in 95% of cases, where there is a whole extra copy of chromosome 21.

- Translocation occurs when an extra part or a whole chromosome is attached to a different chromosome. Translocation occurs in 4% of children born with Down’s syndrome.

- Mosaicism occurs in around 1% of cases and is where there is a whole extra copy of chromosome 21 but in only a percentage of the body cells. The remaining have the normal number of chromosomes.7

Children with Down’s syndrome may be slower to meet their developmental milestones and have learning disabilities, but with the right support and guidance they are able to fulfil their potential and many can live independent lives.

There are some health and eye problems that children with Down’s syndrome are more likely to have, although it is important to remember that many children with Down’s syndrome will not have any other health or ocular complications. Thyroid disfunction and congenital heart disease are two examples of such medical conditions.

More common ocular problems include the following:

- Children with Down’s syndrome are less likely to emmetropise than typically developed children and so ametropia and amblyopia are much more likely.

- Strabismus.

- Brushfield spots (benign white, grey or brown spots found on the front surface of the iris that are formed from an aggregation of connective tissue).

- Approximately 15% of children with Down’s syndrome have nystagmus.8

- There is an increased risk of both congenital and acquired cataract.

- Children with Down’s syndrome are more likely to have eyelid abnormalities such as blepharitis, prominent epicanthal folds, and styes.

- Over 70% of children with Down’s syndrome will under accommodate for near work.9

- Children with Down’s syndrome tend to have a poorer visual acuity compared to typically developed children and consequently have poorer visual performance.10 This means this patient group may need extra support at school and visual tasks may be more difficult, despite wearing their glasses.

Dispensing considerations

Children with Down’s syndrome have facial measurements that differ from typically developmental children, as summarised below:11, 12

- Larger frontal angle

- Larger DBR

- Larger apical radius

- Lower crest height (which is often negative)

- Larger temple width

- Wider head width in younger years but a smaller head width when older

- Smaller pupillary distance

- Shorter front to bend

Clearly patients with Down’s syndrome require a more specialised fit with frames that take into account these typical facial characteristics.

Frame options

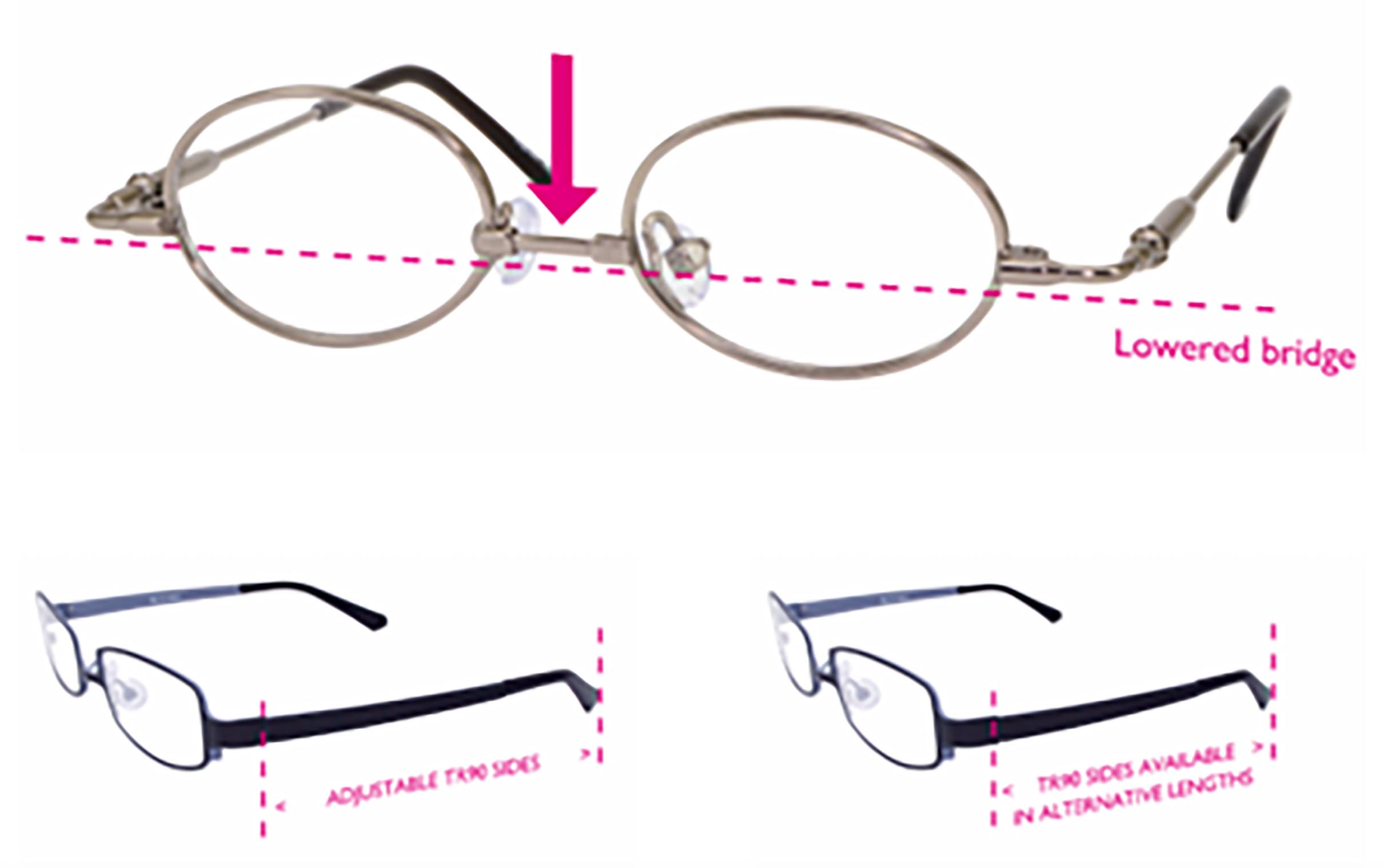

Dibble Optical and Erin’s World have a range of specialised frames for children and adults with Down’s syndrome (see figure 4). The bridge is attached at a point much lower on the nasal rim to account for a smaller crest height, as well as shorter sides that can be easily cropped and adjusted to ensure a suitable length to bend and length of drop.

The wider lugs mean that the boxed centre distance can be kept smaller to match the patient’s PD, while allowing for larger head widths. If a bifocal lens is required, care should be taken to ensure that there is adequate frame depth to accommodate a bifocal, with at least 10mm of distance vision.

Figure 4: Features of the Erins World frame

Tomato glasses are often the most appropriate frame choice for children with Down’s syndrome. Not only are the frames robust, and available in a huge variety of colours and designs, but the frame features and their adjustability make them an ideal choice for children with Down’s syndrome.

Fitting the bridge on the lowest of the three settings (see figure 5), reduces the crest height of the frame and ensures good vertical centration. The one-piece A1 bridge is normally the most appropriate nose pad for broad, flat bridges typical for these children. The sides can then easily be cropped individually to the correct length to tangent, and the glasses can be held securely in place with a strap.

Figure 5: Fitting an A1 one-piece silicone bridge on the middle or lowest setting normally works well for children with Down’s syndrome

In some cases, the length to tangent may need to be shorter than the shortest setting of the side. In this scenario, the side can be cropped to the required length and a further screw hole drilled (see figure 6). For older children and adults, the Junior C range can give a mature look while still providing a great fit.

Figure 6: Drilling an extra screw hole when a shorter length to tangent is required

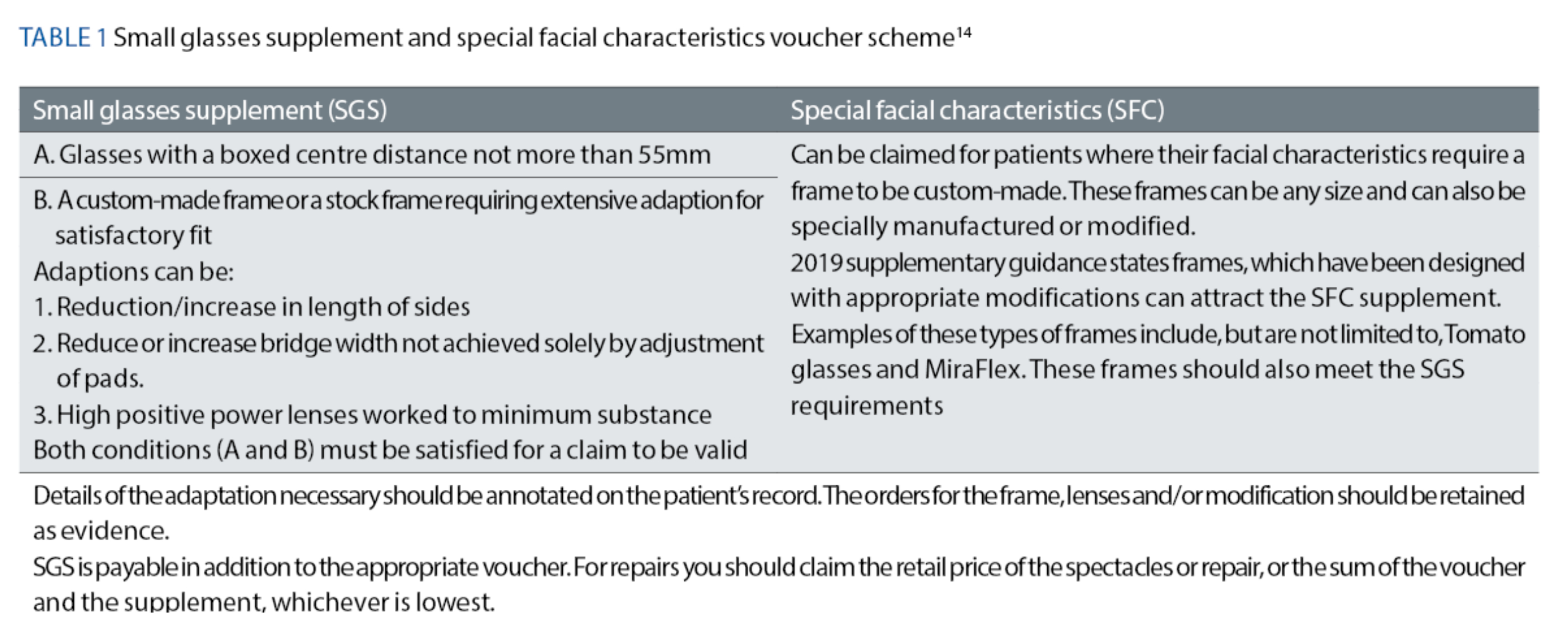

The NHS small glasses supplement (SGS) and special facial characteristics (SFC) as discussed in the previous article should not be overlooked as they provide financial support reducing the overall cost of specially modified or custom made frames – see table 1.

Hypersensitivity

For some children, especially those that are hypersensitive, getting used to wearing glasses can be challenging. These children often will not tolerate anything on their head or face – hairbands, hats or glasses. Children with Down’s syndrome or neurodevelopmental disorders like autism, for example, may struggle to adapt to the feel of the glasses on their face or the way the world looks through the spectacle lenses. The aim for these children is to get them used to the sensation of glasses on their face and to slowly build up wear time.

While fit is still important, the main priority should be dispensing a frame, which the child feels is as comfortable as possible. Something like the Centrostyle frame shown in figure 7 can work well – the lack of nose pads and curl sides means the frame should feel less restrictive and is easier to remove – although this sounds counterintuitive, this can make the child feel more in control and wear time can be increased slowly (even if only a few seconds at a time are managed). Distracting the child with something they enjoy and keeping their hands occupied will hopefully aid adaptation.

Figure 7: Centrostyle ‘Spring collection’ frame. The sides are wrap-around and flexible with a soft rubber lining

Bifocals

Bifocals normally work well for children with Down’s syndrome who have reduced accommodation. Research has shown that the use of bifocals may actually improve a child’s ability to accommodate.9 A +2.50 reading add is recommended for children with Down’s syndrome who under-accommodate, regardless of the amount by which the child under-accommodates (unless they have very poor vision or are very myopic and used to a short working distance).13

Bifocals should be set much higher for children than for adults to ensure use. A large segment such as a D35 should be set at the lower pupil margin. There must be adequate depth in the frame so that there is enough room for the reading area and at least 10mm of clear distance vision at the top. Inset and segment drop should be measured as they will likely differ to adult measurements. As with all first-time bifocal wearers, the glasses should first be worn in a familiar environment when doing close work until the patient is confident enough to wear them outside.

Conclusion

These two articles have considered a variety of paediatric conditions and how they can impact on spectacle dispensing, as well as how the provision of the SGS and SFC supplement can help families with support towards any specialist frames or frame modifications. It is vital to remember that every child is unique and there is not one solution that will work for all children with the same condition.

Some conditions are associated with an increased likelihood of having an eye or vision problem, and these children are also likely to need more specialist dispensing care due to atypical head and facial measurements, or other complexities associated with their conditions. Although these children have a greater need for expert eye care, it is not always possible for families to access this locally. This can be due to a number of factors including a lack of suitable frames, or even limited confidence when dealing with paediatric patients.

With practice, experience, and a little extra care however, it is possible to provide these patients with suitable, comfortable and well-fitting glasses. A simple solution that can dramatically improve a child’s quality of life and help a family navigate the day-to-day challenges they often live with. Hopefully this article has shown that dispensing opticians really can make the biggest difference for little eyes.

- Jessica Gowing BSc (Hons) FBDO is a qualified dispensing optician who has worked in both private practice and a hospital setting. She is a senior dispensing optician at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London where she has been working since 2014. Gowing works as part of a multi-disciplinary team to provide a specialist service for children with a wide range of conditions and complex prescriptions and fitting requirements. Gowing also presents lectures and workshops on paediatric dispensing.

References

- Dutton, Julie Calvert, Deborah Cockburn, Hussein Ibrahim, Catriona Macintyre-Beon Visual disorders in children with cerebral palsy: the implications for rehabilitation programs and school work. Eastern Journal of Medicine. 2012; 17: 178 -187.

- McClelland JF, Parkes J, Hill N, Jackson AJ. Accommodative dysfunction in children with cerebral palsy: a population-based study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 1824-1830.

- Sanjay Marasini, Nabin Paudel, Prakash Adhikari, Jyoti Baba Shrestha, Merrill D. Bowan.Ocular manifestations in children with cerebal palsy. Optometry and vision development. 2011: 42 (3): 178.

- Chenk-Rootlieb AJ, van Nieuwenhuizen O, van Waes PF, van der Graaf Cerebral visual impairment in cerebral palsy: relation to structural abnormalities of the cerebrum. Neuropediatrics. 1994: 25: 68-72.

- Michiyuki Kawakami, Meigen Liu, Tomoyoshi Otsuka, Ayako Wada, Ken Uchikawa, Asako Aoki and Yohei Otaka. Asymmetric skull deformity in children with cerebral palsy: Frequency and correlation with postural abnormalities and deformities. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2012; 45(2): 149-153.

- Sherman SL, Allen EG, Bean LH, et al. Epidemiology of Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13:221–227.

- Types of Down Syndrome. CMDSS. Available at cmdss.org. [Accessed 21th January 2023].

- PADS. Nystagmus in children with Downs Syndrome. DSUK, 2022.

- Al-Bagdady M et al. Bifocal Spectacles as a Treatment for Accommodation Deficit in Children With Down Syndrome. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2009(2443); 50.

- Little, Julie-Anne, et al. The Impact of Optical Factors on Resolution Acuity in Children with Down Syndrome. Clinical and Epidemiologic Research. 2007:48. 3995-4001.

- Thompson, A. Paediatric facial anthropometry applied to spectacle frame design. Aston University. 2021. Dissertation. https://web.archive.org/web/20220506051335id_/https://publications.aston.ac.uk/id/eprint/43749/1/THOMPSON_ALICIA_JANE_2021.pdf

- Margaret J Woodhouse, Stuart J. Hodge, Richard A Earlam. Facial characteristics in children with Down’s syndrome and spectacle fitting. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics. 1994: 14 (1): 25-31.

- Woodhouse, M. Dispensing bifocal spectacles to children (and adults) with Down’s syndrome: Guidelines for eyecare practitioners. Optometry & Vision Sciences, Cardiff University, 2010. Availble at https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/161067/Guidelines-for-Dispensing-bifocals-professionals.pdf [Accessed 21st Jan 2021].

- Association of British Dispensing Opticians. Making Accurate Claims in England 2022. Available at: https://www.abdo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/MACE-guide-2022.pdf [Accessed 20th January 2024]