Domains and learning outcomes (C110164)

• One distance learning CPD point for optometrists and dispensing opticians.

Communication

(s.2.1) After successful completion of this CPD practitioners will be able to explain to patients, parents and carers what constitutes an optimal fitting for ophthalmic frames considering facial anthropometry, frame measurements and prescription using professional judgement to adapt language and communication approach accordingly.

Clinical practice

(s.5.3) After successful completion of this CPD practitioners will be able to evaluate the key associations between facial anthropometry and frame measurements to determine the optimal fitting of ophthalmic frames and apply this to their clinical practice.

“I believe that dispensing is just as important as refracting as it is, after all, by the final product, the pair of spectacles, by which you will most frequently be judged. Most of my patients who complain of their glasses are dissatisfied with the dispensing rather than the refraction. One group of dispensing problems comprises ill-fitting frames…

The cure… is to improve standards of dispensing… and it could be argued that in not offering the client the best dispensing advice you are failing in your professional duty.”

Prof John Weatherill, Owen Aves Memorial Lecture, 1988

At its most basic, a spectacle frame is a medical device or optical appliance that will hold prescription lenses in front of your eyes to make the most of your vision. In 2024, we have a massive amount of choice when it comes to selecting spectacle frames, however, not every frame will be the same in terms of fit, comfort or durability. The selection of frames can be bewildering, especially if you have not worn an optical correction before. Eye care professionals (ECPs) regardless of role, and some skilled trained optical assistants can help navigate the numerous choices and select a suitable frame for each patient.

As the above text from Professor Weatherill indicates, the fit and comfort of a spectacle frame is often what an ECP is judged on, not the clarity of vision, or the detail of the eye examination, but having a constant reminder that their frames are uncomfortable, slipping forward, gripping their temples or at worst painful and sore.

It is also worth noting that in the General Optical Council standards of practice, all registrants (and those under their supervision in the case of regulated dispensing) should ‘reflect on your practice and seek to improve the quality of your work’1 and only provide or recommend examinations, treatments, drugs or optical devices if these are clinically justified and in the best interests of the patient.2

The selection and fitting of spectacle frames could be considered as both an art and a science. An art because, as a medical device, wearers will demand it to be aesthetically pleasing to the eye, not only their own but to peers and onlookers, and a science in that structure and construction are intrinsically linked to facial features and fitting different individual parameters.

What’s the science behind a good fitting frame?

A good fitting spectacle frame should consider both morphology and anthropometry.

Morphology relates to the science of form, in particular the outer form and inner structure (the fitting of frames is more concerned with the outer form of the human head), and the development of, living organisms and their parts. Anthropometry concerns itself with the measurement of the human body. Both are relevant to the design and fitting of ophthalmic frames.

In addition to these two fundamental considerations, patients will all be different – some large, some small, differing positions of certain facial features, such as; eyes, nose, ears, mouth, eyebrows, eyelashes, temples and heads and of course no one is perfect. Most patients are asymmetric despite believing that each side of their face is identical. Add into the mix, differing ethnicities and pathological conditions, which may cause facial or cranial abnormalities such as craniosynostosis or microtia3,4 and it is easy to see why one size really does not fit all.

Where should I start?

Spectacles are required to be worn on the face (unlike contact lenses which are worn on the surface of the eye) and therefore need to be anchored securely to enable good visual acuity. This is especially important in the case of high spherical or more especially astigmatic prescriptions. Visual acuity will be compromised if the frame slips forward altering the effective power of the lenses or if they are not sitting in the correct horizontal or vertical plane.

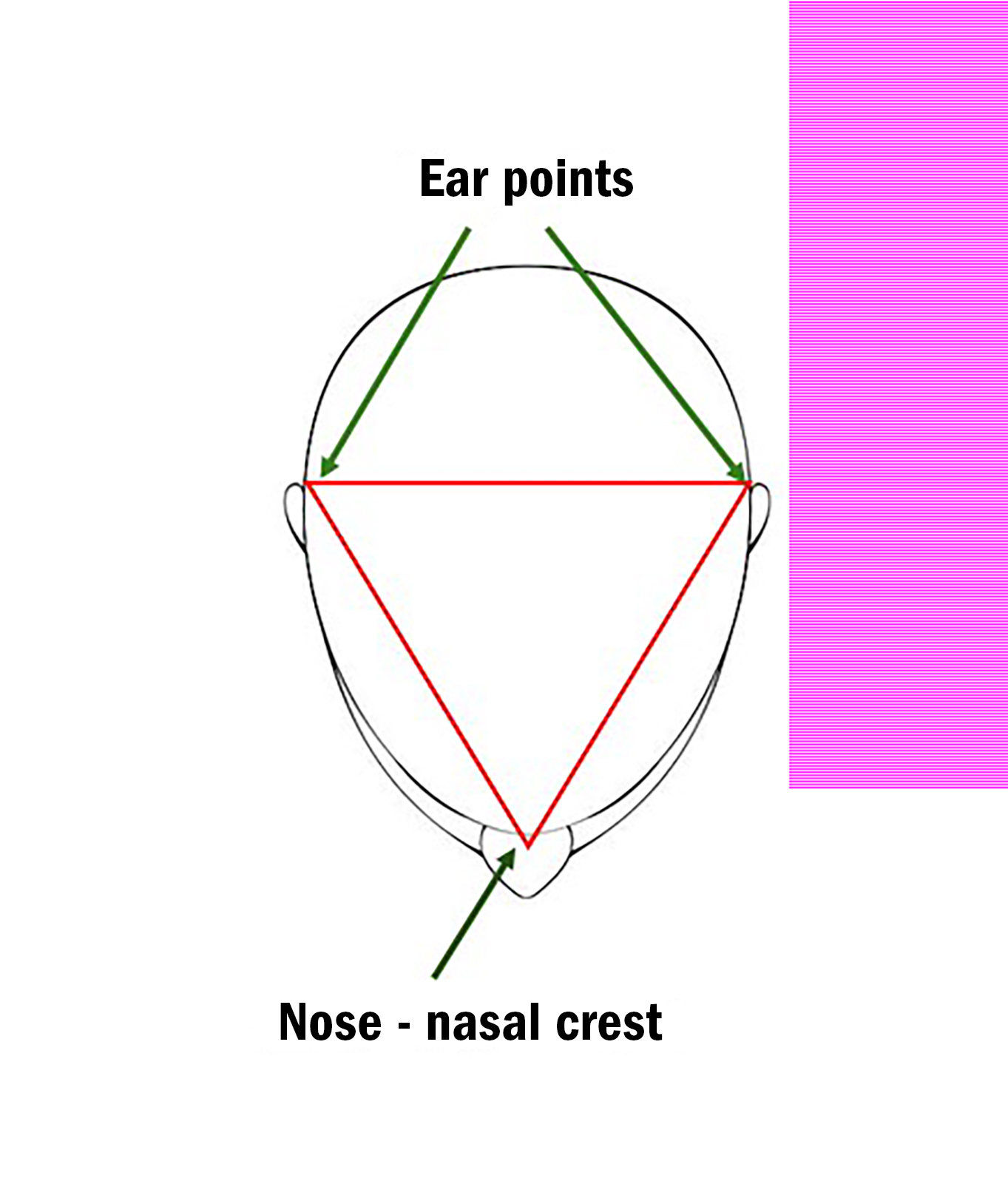

Figure 1 (below) clearly shows the three main ‘anchor’ points of a spectacle frame being the nose and the two ear points. The ideal ‘fit’ should be first assessed at the bridge and then working back via the lug points of the frames to the ear tip points – the weight of the spectacles should be evenly distributed between these three points.

The nasal area will be the major bearing surface and largest area of contact between the front of the frame and the face, especially in a plastics frame. Similarly with a metal frame with pads on arms – the pads will bear the bulk of the weight so good alignment with the bridge is essential.

Another constraint is the width of the front of the frame – it corresponds with the temple width of the face – too wide and the frames may slip forward and too narrow the sides will dig in at the temples and push the frame off.

It’s all about fit

A well-fitting frame should sit comfortably on the nose, be well balanced and have the eyes positioned as centrally as possible in the horizontal plane with enough depth to accommodate the lens design (more important when dispensing progressive power lenses) and allow the wearer to look through the optical centre of the lens.

The example in figure 2 on the right shows a circular plastics frame, which has the eyes well centred in both the horizontal and vertical planes with a wide enough temple width to be comfortable and not dig in. The example on the left shows a frame that is clearly too big for the teenager, the frame is so deep that the wearer is looking over the lens.

There are a few measurements that can be taken from faces and frames that can help achieve a ‘good’ fit. We will now look at these measurements in more detail.

Figure 2: A good fit compared a poor fit

Measuring for success – Facial Measurements

There are many frame and facial measurements that can be taken in optical practice to ensure a better fit, sadly many optical professionals do not showcase their skills and knowledge possibly due to time constraints in a busy practice or by compromising on fit and dispensing a stock frame.

In the author’s experience, while time can be devoted to taking a full set of facial measurements, then choosing a frame that closely matches these parameters, this is seldom done as often patients are much more concerned with how they will look in their new eyewear rather than how they will see through them. As professional ECPs we must balance the clinical aspects with aesthetics for a positive outcome. This said however, the author finds the following measurements helpful when dispensing – especially complex dispensing or paediatrics.

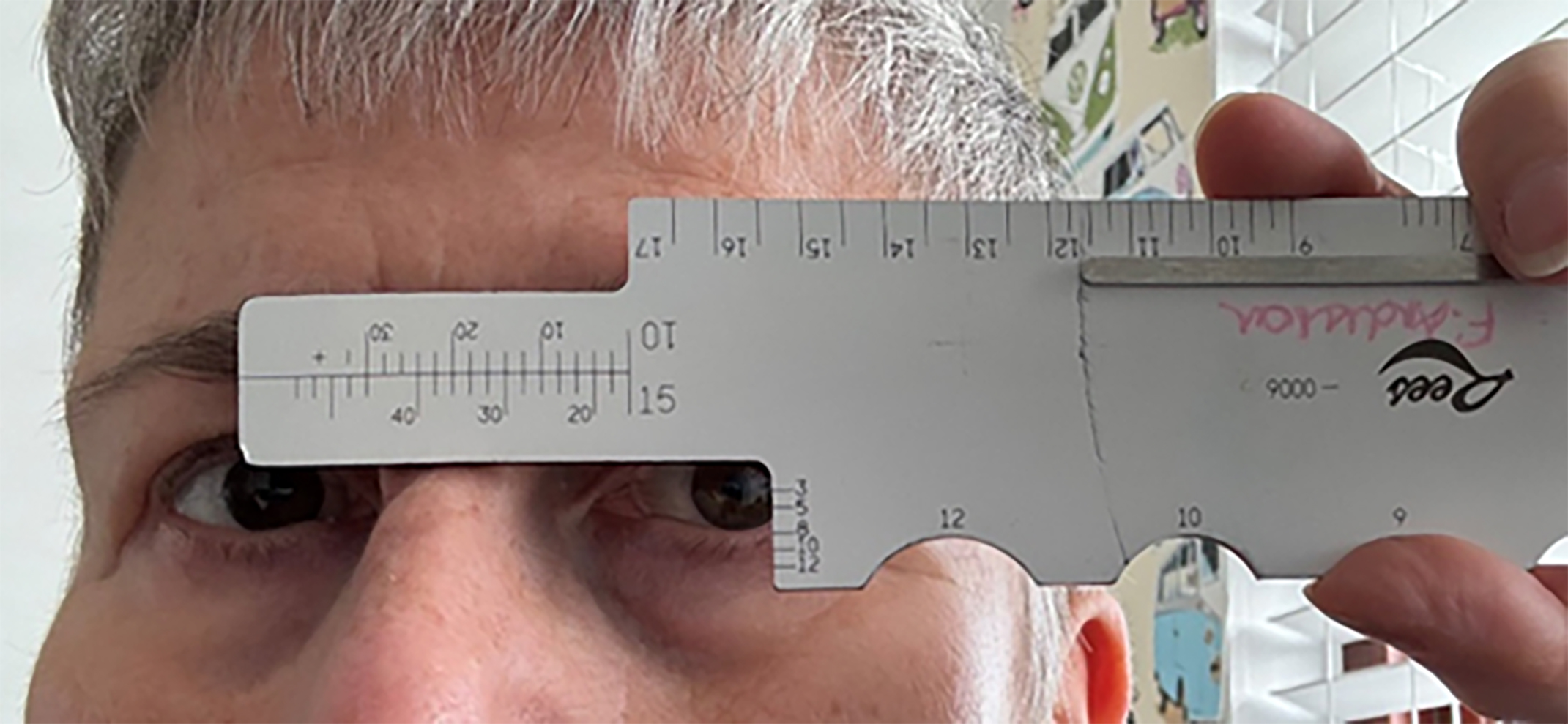

Crest height: This is the vertical distance from the lower limbus to the bearing surface of the nose in the plane of the front.5 The crest height will determine where the frame will sit on the nose. Children tend to have lower crest height measurements when compared to adults due to the growth and development of the nose as they increase in age – the bridge tends to lift and grow away from the face raising the height of the crest.6

Figure 3: The measurement of crest height with a facial gauge

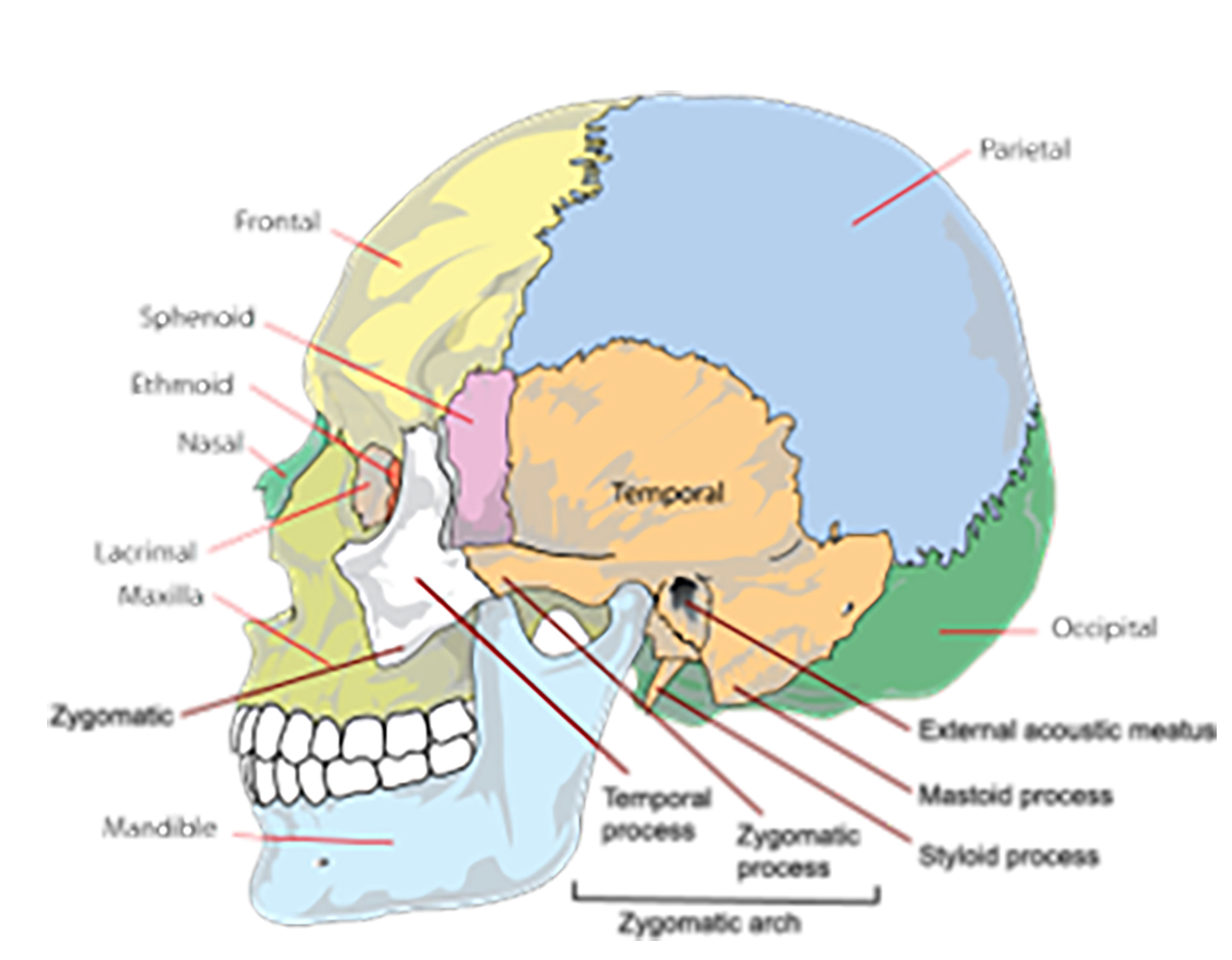

Temple width: This is the distance between the temples on the patient. The temple of the head is also known as the pterion,7 it is a latch where four skull bones fuse: the frontal, parietal, temporal and sphenoid. It is located on the side of the head behind the eye between the forehead and the ear.8, 9

Figure 4: The temple on the human skull

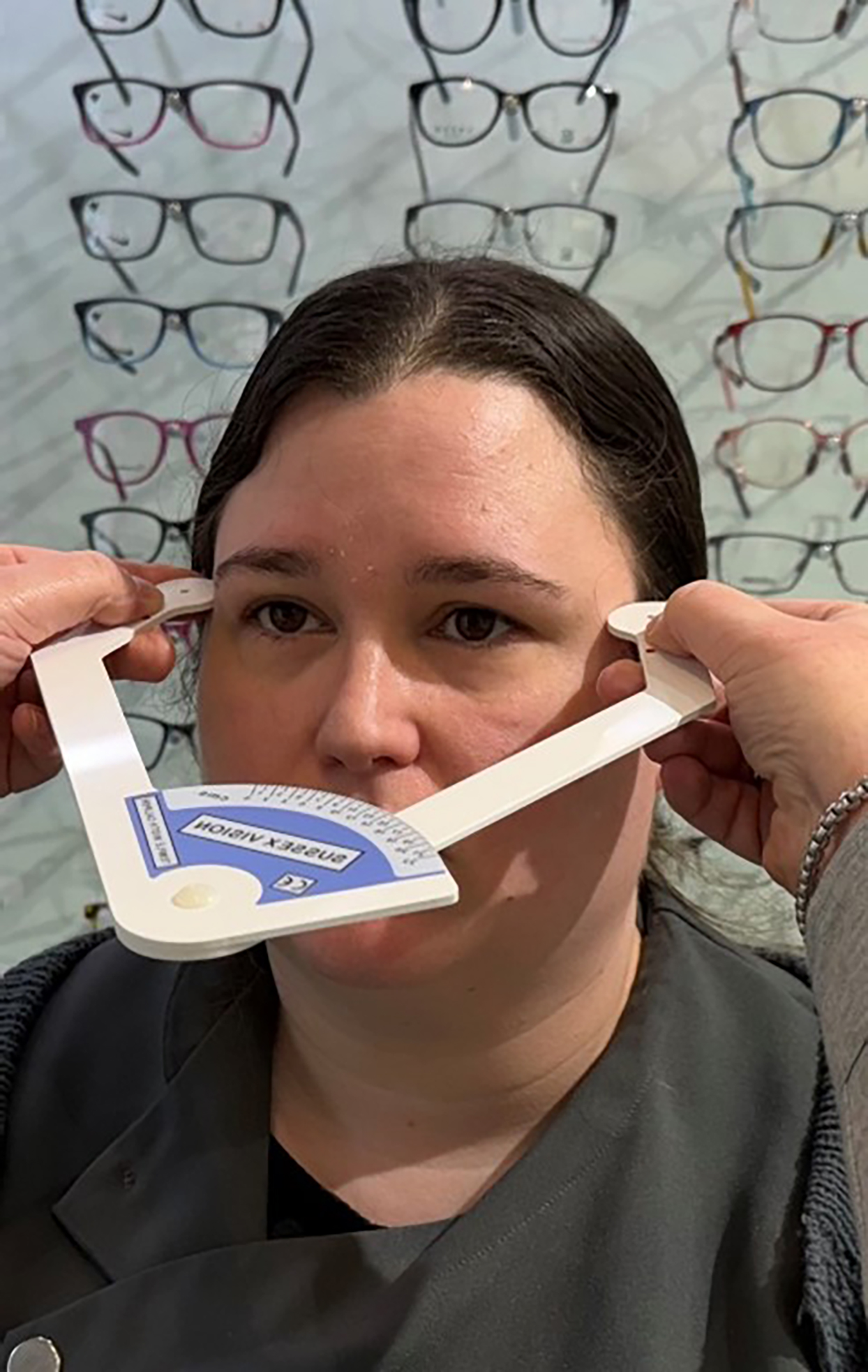

Head width: This is the distance between the ear points, the ear point sits in the uppermost part of the groove between the ear and the skull.5

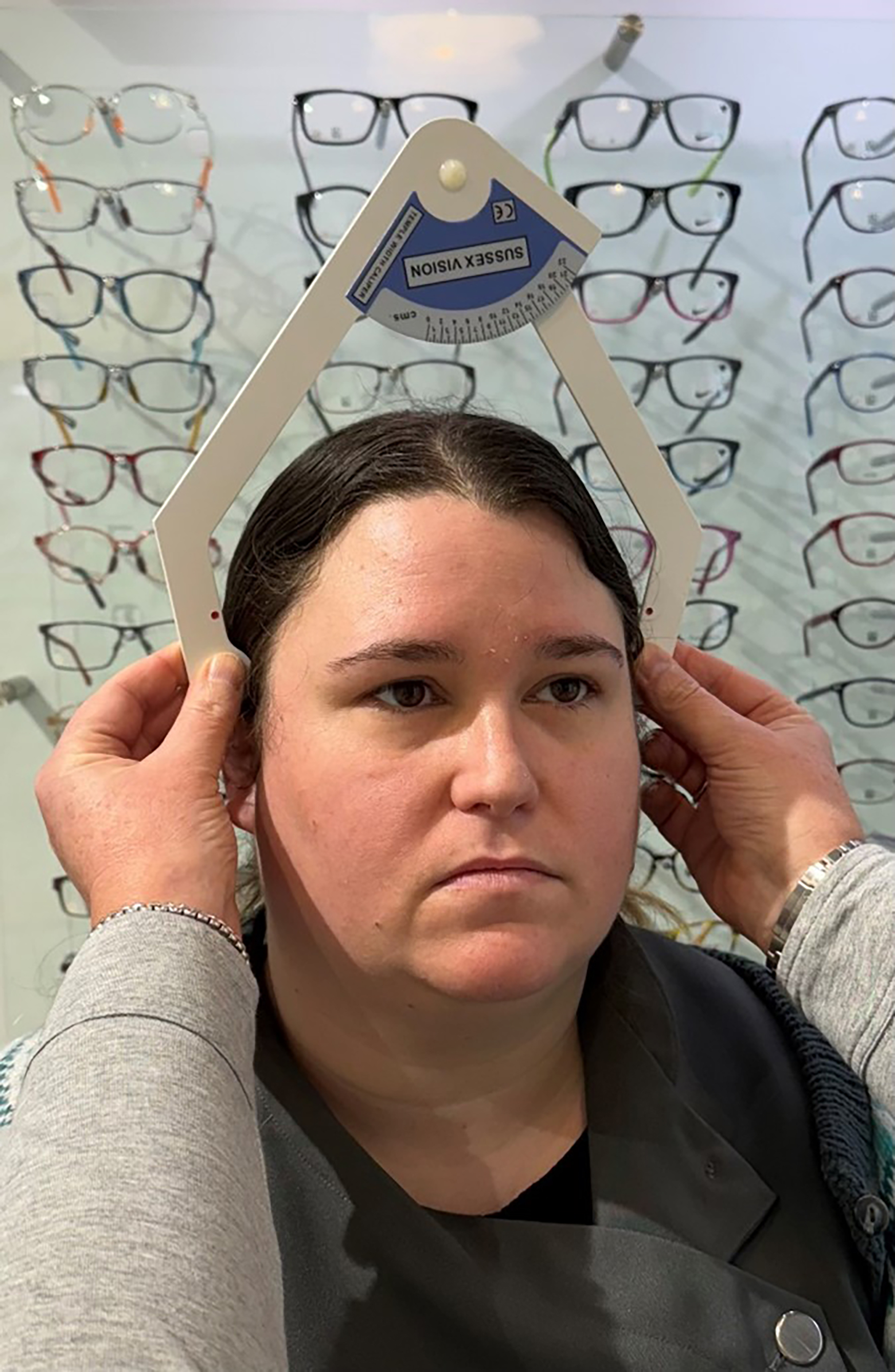

Figure 5: The measurement of temple width with callipers

Measuring for success

Frame measurements are similarly useful when dispensing and helping patients select a suitable frame. If the ECP has previously taken facial measurements this will aid selection.

Crest height ensures the front of the frame sits in an appropriate position on the face. The rule of thumb is that the eyes sit centrally within the frame – ideally on the mid-point or horizontal centre line (HCL). With modern fashion frames this is often just not possible however, so long as the lenses are correctly centred taking into account the pantoscopic angle this will ensure optimum visual acuity should be achieved.

Temple width can aid the selection of a suitably sized frame. The size marked on a frame will detail the eye size and bridge size. Whilst different manufacturers may use different methods of measuring and recording frame sizes, the numbers stamped on a frame give a skilled practitioner a notion of what frames to select for their patient to try on. The measurement of temple width further enhances and narrows the selection as it can give a pretty accurate approximation of the width the front of the frame will need to be to fit comfortably.

The temple width measurement is particularly helpful in selecting an appropriate frame as it suggests an appropriate size for the front.

Figure 6: The measurement of head width with callipers

Relating frame and facial measurements

Temple width as measured on patient = 115mm

Frame size stamped on selected frame = 45 x 16

Total frame dimensions = R eye 45 + 16 + L eye 45 + R lug 5 + L lug 5 = 116mm

It is safe to assume that the chosen frame will be a suitable size as the front of the frame is almost exactly the same size as the measured temple width.

The measurement of temple width on a frame is taken 25mm behind the assumed plane of the front of the spectacle frame. This measurement corresponds to where the facial measurement would be taken.

Head width is another measurement which is useful when setting up a frame prior to collection. If the head width measurement is taken at the time of dispensing, then the frames can be ‘set up’ to reflect that measurement and only minimal adjustments may need to be made at a collection appointment.

Often the facial measurement is recorded as the actual measurement value – this is referred to as the uncompensated head width. When setting up the frame the compensated value is usually achieved by reducing the total head width measurement by 5mm each side (10mm in total) to increase grip and achieve a secure fit. It should also be noted that the length to bend, inward angle of drop and angle of let back all influence the final fitting of the frame.

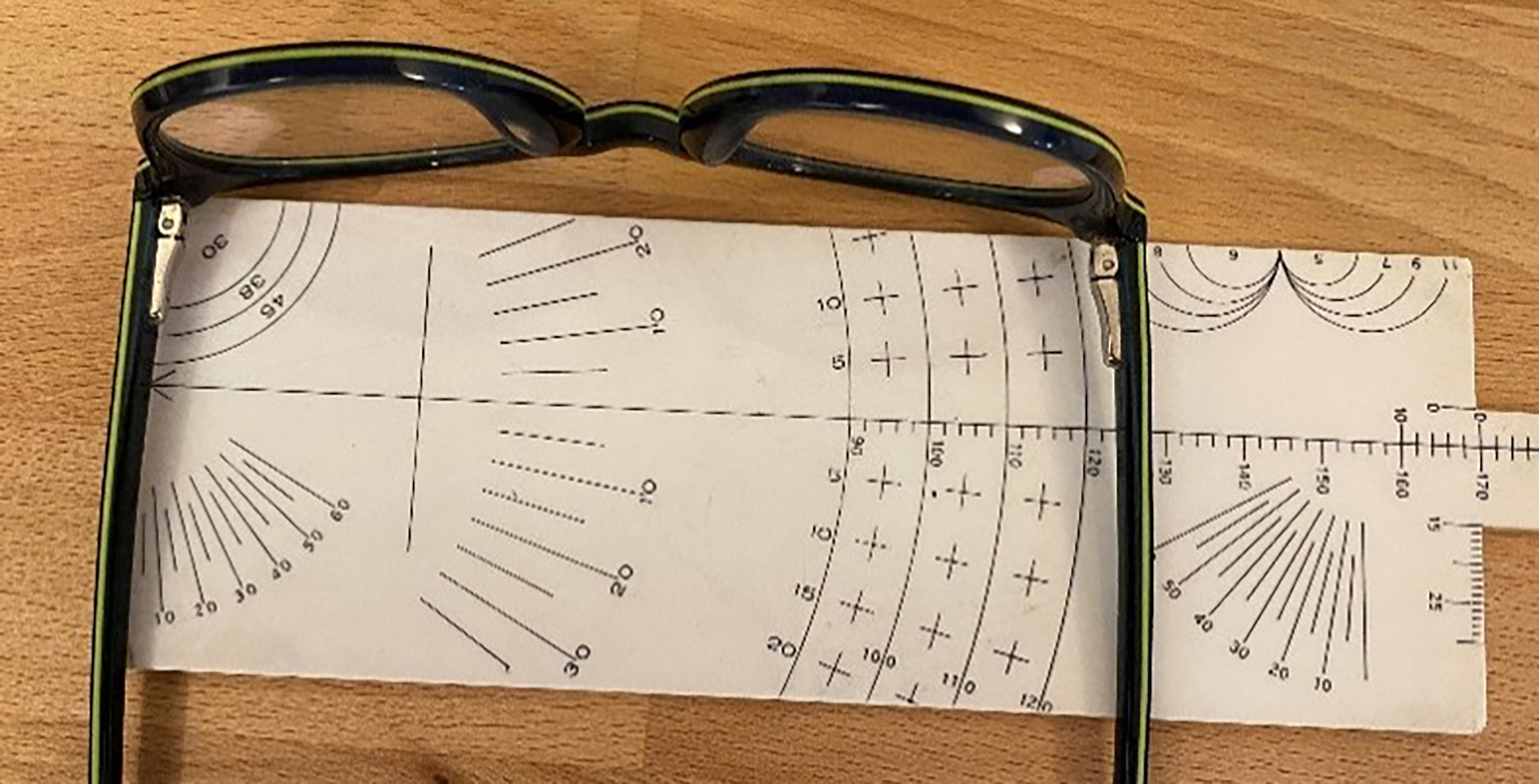

Figure 7: Crest height as measured on a frame

Figure 8: Temple width measured on a frame

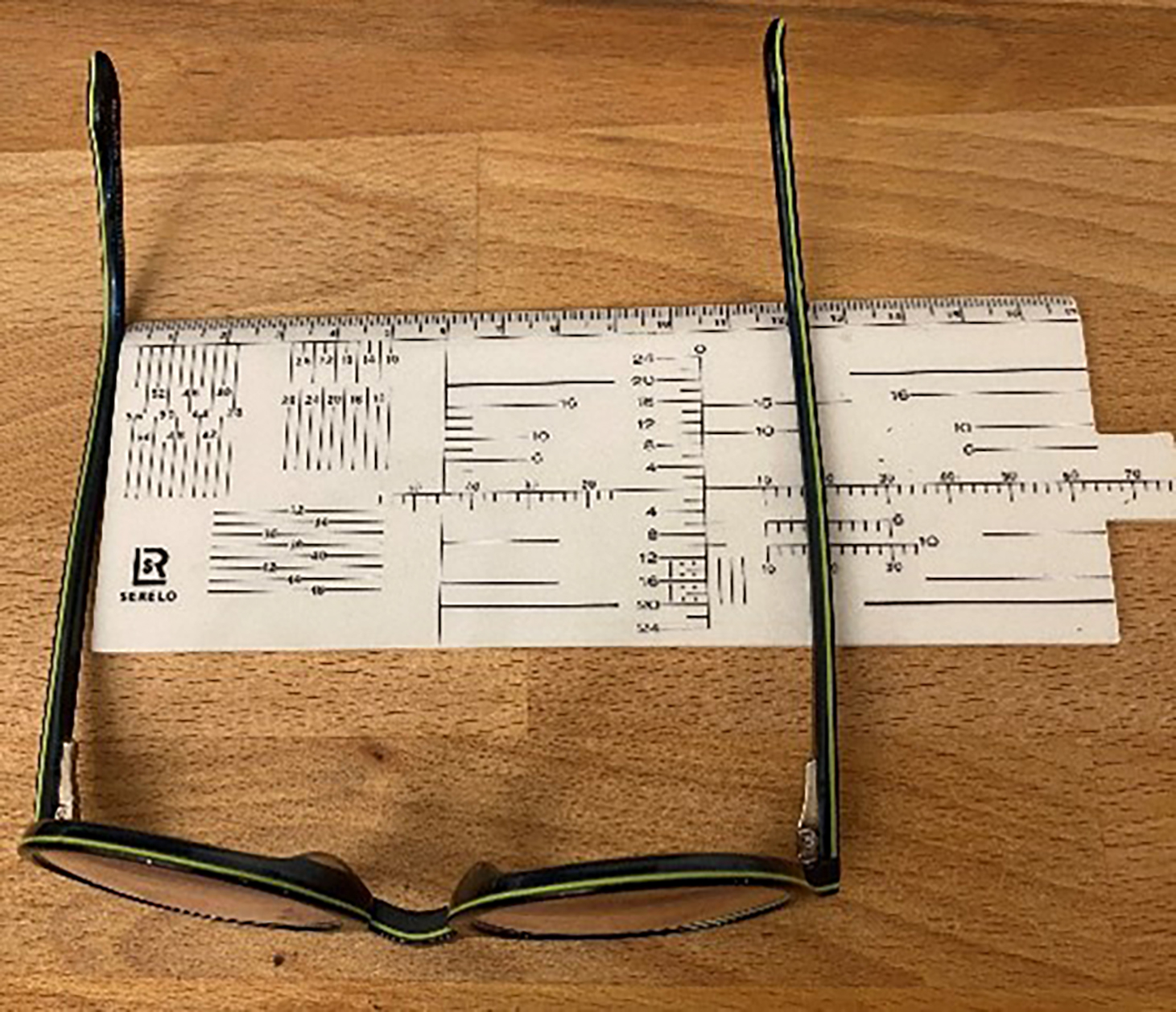

Figure 9: Frame head width

Frame Materials

A comprehensive analysis of spectacle frame materials is beyond the scope of this CPD article – it is a colossal subject in its own right – however, it is worth noting that different materials have different construction methods and this impacts on the overall fit and aesthetics of a spectacle frame.

Most modern materials are lightweight and robust and can be adjusted to improve the fit and comfort for the wearer, yet, one of the biggest causes of patients returning to an optical practice is because their spectacles do not fit, slip down or even hurt. Many patients do not return to their optical practice and suffer in silence when often a minor adjustment or tweak to the fit is all that is required.

Plastics frame materials – a good fit for the patient should distribute weight between the principal bearing surfaces of the nose and ears. Despite this, plastics frames do require adjustments and refitting from time to time. Plastics materials will alter with excessive heat, if left in a hot car for example, or if a patient is heavy handed and continually removes their spectacles with one hand then the angle of let back may become enlarged resulting in the fit being altered. All optical practices should offer an ongoing aftercare service to their patients and advise them to return regularly to have the fit and adjustment of their spectacles checked and monitored.

Metal frames with pads on arms – are not immune from straying from the perfect fit. Again, poor handling can increase the angle of let back of the lug and render the frame unstable. Nose pads are notorious for needing to be replaced it is also not uncommon for patients to experience discomfort from older, more brittle nose pads and may require them to be replaced at regular intervals, or at the very least adjusted to ensure as much of the surface area as possible remains in contact with the bridge of the nose to ensure optimum weight distribution.

An added drawback with non-hypoallergenic metal materials is that if a frame is very out of alignment and any of the frame comes into contact with the skin the patient may experience contact dermatitis symptoms due to a reaction between their skin and the metal compound, hence, it may be of even more importance to have regular checks and adjustments if the frames are made from metal as often more allergies are reported from these materials.10

Summary

In conclusion, the skills of registrant opticians whether dispensing opticians or optometrists and well-trained optical assistants or frame stylists can enhance the patient journey for many. Choosing the right frame not only looks good but feels good; often so good that patients forget they are wearing spectacles.

- Fiona Anderson BSc(Hons) FBDO R SMC(Tech) FEAOO is past president of the International Opticians Association, ABDO past president, past chair Optical Confederation, Optometry Scotland member, past Grampian AOC member, EAOO – co-opted trustee, ECOO European Qualifications board member, Renter Warden: Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers, Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers Liveryman & Fellow of the European Academy of Optometry & Optics.

References

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians, s5. Keep you knowledge and skills up to date. London: General Optical Council; 2016 p 10.

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians, s7.6 Conduct appropriate assessments, examinations, treatments and referrals. London: General Optical Council; 2016 p 12

- Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children. Conditions treated by the craniofacial unit. Available at: https://www.gosh.nhs.uk/wards-and-departments/departments/clinical-specialties/craniofacial-information-parents-and-visitors/conditions-we-treat/ [Accessed 30th September 2024]

- 20/20. Fitting the Un-Triangle. Available at: https://www.2020mag.com/article/fitting-the-untriangle-p2p-080524#:~:text=When%20fitting%20a%20microtia%20ear,ear%2C%20and%20the%20right%20ear. [Accessed 30th September 2024]

- Obsfeld H. Spectacle Frames and their Dispensing. London: WB Saunders Company Ltd; 1997 p 132

- Thompson AJ. Paediatric Facial Anthropometry Applied to Spectacle Frame Design. Available at: https://research.aston.ac.uk/files/60296803/THOMPSON_ALICIA_JANE_2021.pdf [Accessed 30th September 2024]

- Adejuwon SA, Olopade FE, Bolaji M. Study of location and morphology of the pterion in adult Nigerian skulls. ISRN Anat. 2013. E403937. https://doi.org/10.5402%2F2013%2F403937

- Obsrfeld H. Spectacle Frames and their Dispensing. London: WB Saunders Company Ltd; 1997 p 133

- Maseedupalli S, Priyanka PV, Konda S, Kolli LN. Head and facial anthropometry of the Indian population for designing a spectacle frame. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023; 71(3): 989-993.

- Walsh G. Materials and allergens within spectacle frames: a review. Contact Dermatitis. 2006; 55(3): 130-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0536.2006.00791.x