Domains and learning outcomes (C109481)

• One distance learning CPD point for optometrists and dispensing opticians.

• Clinical practice

Upon completion of this CPD, ECPs will be able to describe potential risk factors for presbyopia, including early onset presbyopia (s5)

• Communication

Upon completion of this CPD, ECPs will be able to improve communication with patients about presbyopia through a greater awareness of the financial and psychological burdens that may accompany presbyopia (s2)

One of the few aspects of life that is guaranteed is that we will get older. While we gain wisdom from our life experiences, there is often negative stigma associated with some of the changes that occur to our body and mind with advancing age. Interestingly, the World Health Organization believes that most developed world countries characterise old age from 60 years and above, and estimate that between 2015 and 2050 the global proportion of this age group will nearly double from 12% to 22%.1

In optometric practice, part of our regular bread and butter work includes diagnosing, communicating and managing presbyopia, which is often one of the first ocular signs of ageing. This article highlights the key findings from the BCLA CLEAR presbyopia publication relating to the epidemiology, and impact of presbyopia.2

Definition of presbyopia

Across the literature there are various selection criteria for presbyopia, which makes making prevalence comparisons challenging. Some studies rely on visual near vision performance alone, whereas others include a comprehensive battery of clinical tests.

The global consensus definition in the BCLA CLEAR presbyopia publications is:

‘Presbyopia occurs when the physiologically normal age-related reduction in the eye’s focusing range reaches a point that, when optimally corrected for far vision, the clarity of vision at near is insufficient to satisfy an individual’s requirements.’3

The two main ways presbyopia has been classified are:

- a) Functional presbyopia where there is reduced near vision (N8 or less, which is approximately 0.4 logMAR) which can be corrected to improve vision. Logically, this would mean that those whose myopia handily provides good near vision uncorrected would be exempt from studies using this approach.

- b) Objective presbyopia where distance refractive error has been fully corrected and there is near vision of N8 or less due to the associated loss of accommodation. This criterion includes all refractive errors. The definition of accommodation is the change in optical power due to the crystalline lens changing shape and position.

Prevalence of Presbyopia

Naturally studies using functional presbyopia assessments have reported lower overall prevalence levels. In 2015, it was estimated that around one in four people across the world (24.9%) had functional presbyopia, which equates to approximately 1.8 billion individuals.4 When considering the BCLA CLEAR presbyopia definition, this increases to nearer to one in three people (31.7%, 2.3 billion individuals).

The changing population dynamics means the prevalence may well have peaked around 2020 and by 2030 there are likely to be over two billion individuals with functional presbyopia or over three billion when applying the latter criteria (figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of presbyopia, colour coded per research methodology

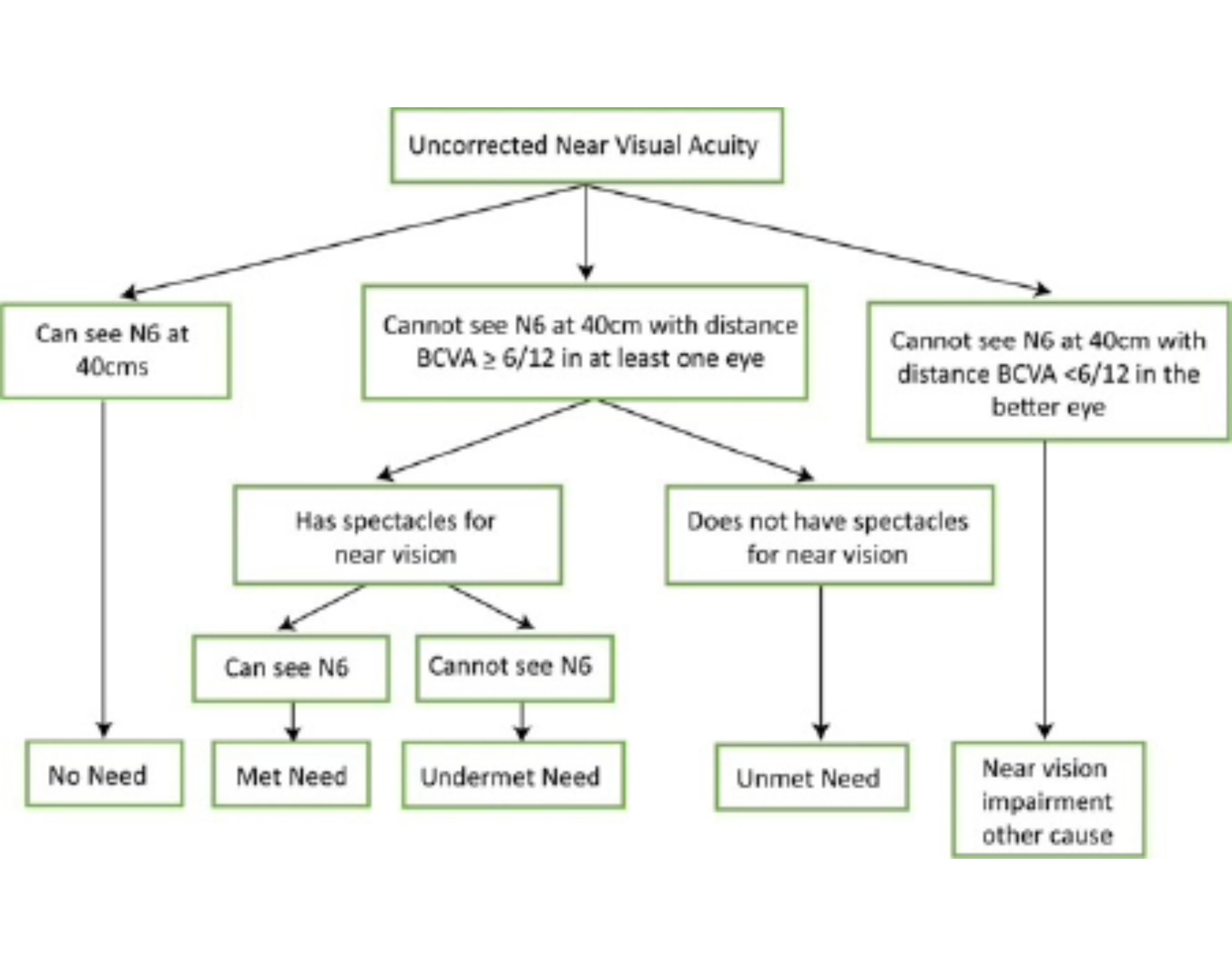

Near effective refractive error coverage (Near eREC)

This represents the proportion of the population that has their near refractive correction with a good quality outcome.

The global near eREC is around one in five adults (20.5%, for adults who are 50 years or over), which is lower than for distance eREC (42.9%),5 promoting the World Health Assembly to set a 40% increase target for near eREC by 2030.

For consistency best practice guidance for near eREC visual assessments include using Times New Roman N6 or N8 font size at 40cm and ensuring distance vision is 6/12 or better, to exclude pathology that may be impacting visual performance. LogMAR is preferable over Snellen acuity measurements.

Figure 2 highlights the inclusion protocol.

Figure 2: Flow chart protocol for near eREC assessments, based on near acuity in the better eye

Uncorrected Presbyopia

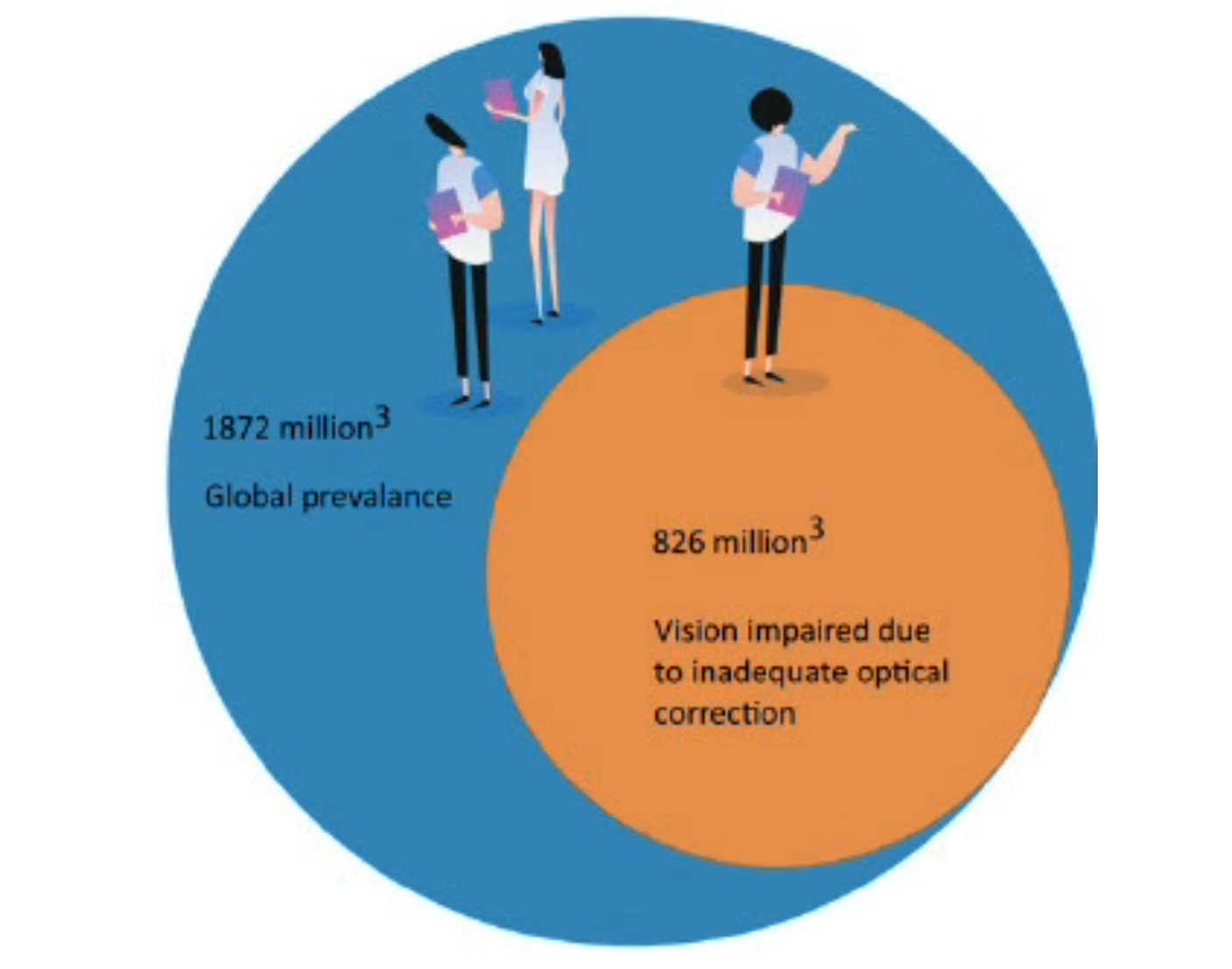

Unfortunately, too many people (1,872 million) suffer from uncorrected or sub-optimal correction of presbyopia, despite the wide range of management options available. This comes with high consequences (figure 3) with too many suffering from visual impairment (826 million) and feeling disabled.

Researchers have revealed that overall refractive error causes more vision impairment at near than in the far distance and the prevalence of uncorrected near vision maybe six times larger than that for uncorrected distance vision.

Figure 3: Statistics relating to uncorrected presbyopia

Risk factors for presbyopia

Although age is just a number, this has the highest single association to presbyopia, with the prevalence increasing with old age. Generally, you would expect patients to start presenting with issues between 40-49 years old (27.6%), although some will present younger, especially if they have multiple risk factors. Nearly all adults will experience presbyopia by 60-69 years old (81.8%). The prevalence of uncorrected presbyopia also increases with age, although there appears to be one exception – in rural Japan; it will be of great interest what learnings can be drawn from this unique society.

Near eREC has been found to increase from around half (47.4%) among 30-49-year-olds to three-quarters (75.7%) in those over 70 years of age.

There are also regional differences with the lowest prevalence levels reported in Central Africa (under 15%) and the highest in Western Europe (which could be nearly 50% depending on the study methodology).

South Asia has the largest number of uncorrected presbyopes (275 million). The best location, in terms of near eREC is Los Angeles (87%) and the worse is Tripura in India (0.3%), showcasing the huge differences across the globe, favouring those in high income countries.

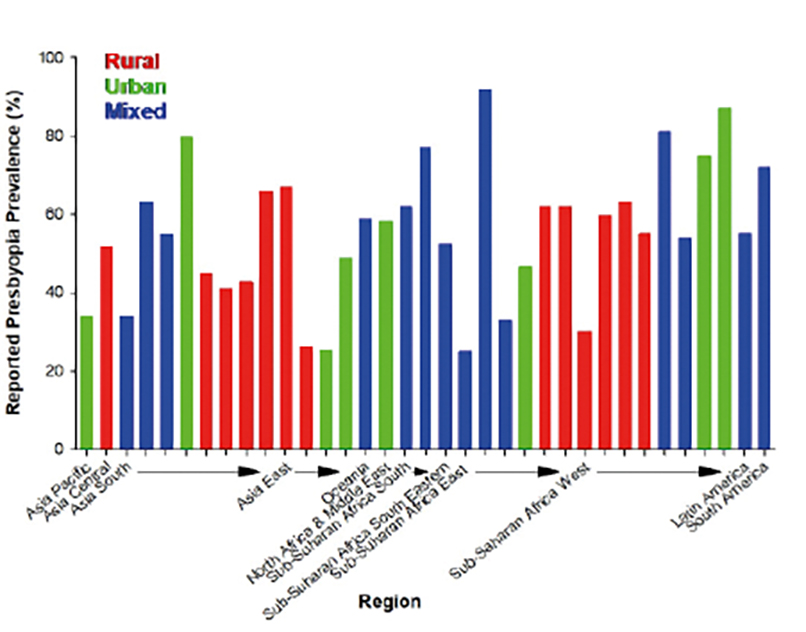

Urban locations tend to have higher prevalence rates (25-80%), when compared to rural populations (36-67%), although there is a large variation (figure 4). Some studies have suggested these differences may only be significant in countries with a low/medium development index and therefore be more related to differing economic conditions. Areas with high air pollutant concentrations have also been linked and may double the prevalence of presbyopia.

Figure 4: Presbyopia prevalence in different locations

Women show a higher prevalence of presbyopia than men, when matched to the same age group, possibly due to the typical tasks and viewing distances utilised. This is interesting as generally males have lower accommodation levels. The findings for near eREC are mixed when comparing males and females.

Socioeconomic status, literacy and education, health literacy and inequality are not easy to isolate from other aspects, although are likely to be lower contributing factors to presbyopia. These associations tend to be plausible rather than proven and include refractive error, diet, ultraviolet radiation (UV), systemic disease and type of work. Equally there may be conflicting outcomes, for example an office-based worker in a higher socioeconomic setting may minimise their exposure to UV/air pollutants but the increased near vision demands may elicit near vision symptoms sooner, when compared to an individual working in a lower income outdoor environment. As with any disease, having access to good education and care is important to maximise awareness and for optimal management of presbyopia.

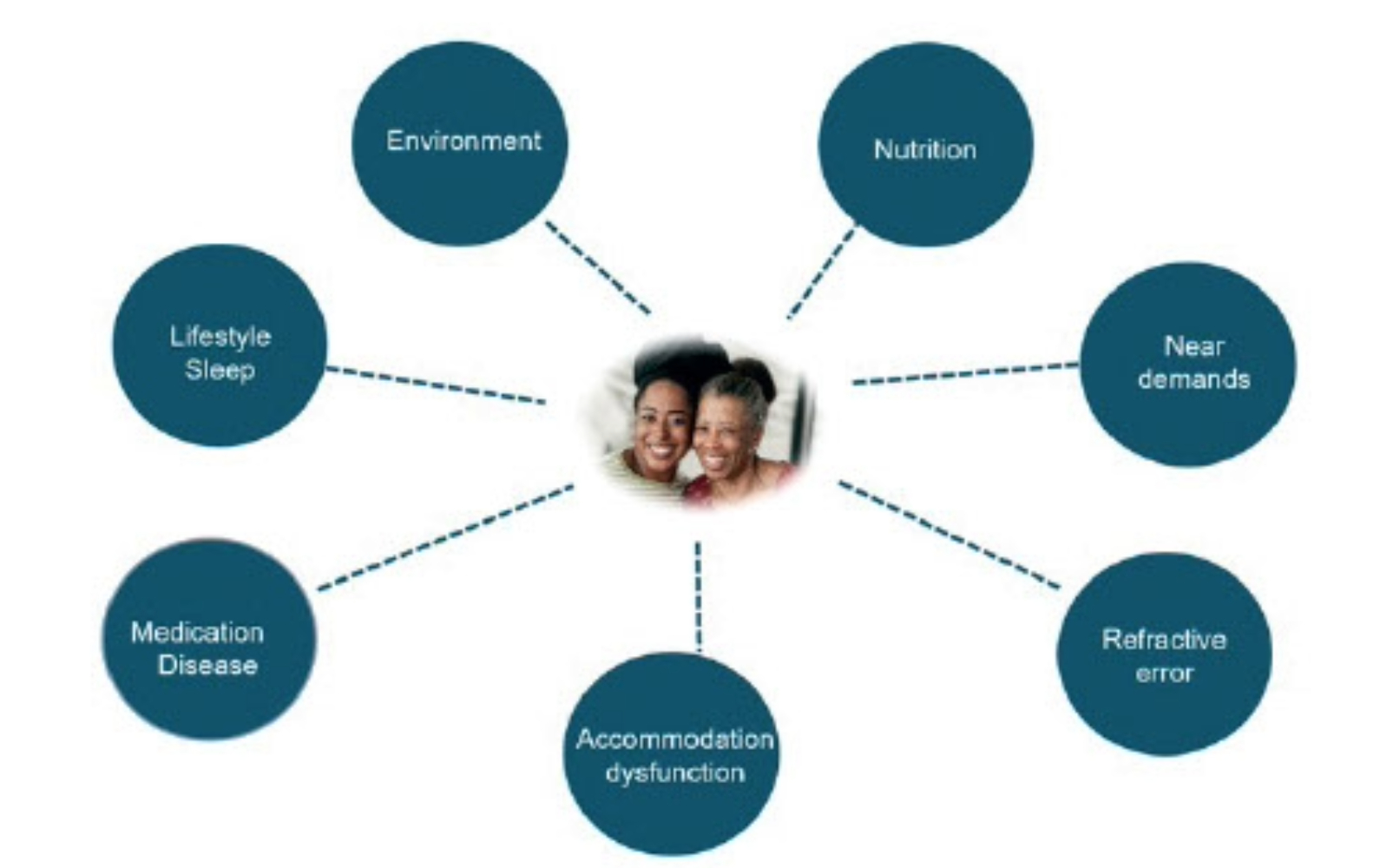

Risk factors for early onset of presbyopia

Comprehensive history taking may identify clues as to those more likely to have presbyopia sooner than usually expected (figure 5).

Figure 5: Risk factors for early onset of presbyopia

In general, environmental aspects such as living in closer proximity to the equator, at lower altitudes where temperatures are hotter and greater toxic exposure areas have been associated with earlier onset of presbyopia. There have been inconsistent findings related to UV, however there may be benefit from utilising UV blocking devices to maintain accommodation ability for longer periods.

A poor diet, especially with insufficient essential amino acids or antioxidant nutrients, may induce presbyopia earlier as they help support healthy functioning of the crystalline lens.

Of interest is how the use of digital devices is influencing our near demands and accommodation amplitude, potentially contributing to the emergence of presbyopia.

Refractive error has been linked to the inception of presbyopia based on the logic that eyeball size may influence accommodative power and due to changes to accommodative demands from different powered spectacle lenses. This suggests spectacle corrected hyperopes become presbyopic earlier than those with no or myopic refractive errors.

Of note some individuals will naturally have lower than average accommodative amplitudes or be taking medications that block acetylcholine neurotransmitters, which reduce accommodative ability. Some examples include:

- Anticholinergics

- Antipsychotics

- Antihistamines

- Antidepressants/anti-anxiety drugs

Diuretics can also lead to lenticular dehydration through changing the balance of fluid. Some non-prescription/recreational drugs can also have consequences resulting in accommodation disorders, which may be transient changes or dosage-related.

On the other side of the coin some medications may potentially hinder the birth of presbyopia, such as pilocarpine by stimulating muscarinic receptors and accommodative activity.

Any ocular condition that causes damage or impact to the lens or ciliary muscle is more likely to induce presbyopia, for example trauma, aphakia, iridocyclitis, Aide’s syndrome. Associated systemic conditions include:

- Diabetes

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myasthenia gravis

- Down’s syndrome

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Good sleeping patterns are beneficial for many reasons and may have protective properties that contribute to helping reduce presbyopia progression according to one study. Ageing reduces the amplitude of the circadian rhythm and its response to light; older age has been associated with sleep disorders.6

Quality of life impact of presbyopia

Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs ) are a useful way to determine how presbyopia may be impacting an individual’s quality of life. Several presbyopia specific questionnaires have been developed and some examples include:

- Near Activity Visual Questionnaire (NAVQ)

- Near Vision-related QoL questionnaire (NVQL)

- Presbyopia Impact and Coping Questionnaire (PICQ)

- Near Vision Presbyopia Task-based Questionnaire (NVPTQ)

- Activities of Daily Living (ADL) framework

There are also relevant non-presbyopia specific questionnaires that can be effective for comparing presbyopia treatment options. For example, the National Eye Institute Refractive Quality of Life (NEI-RQL), which has been used to reveal a better outcome and functional vision preference for multifocal contact lenses over monovision contact lenses. There are also positive PROMs findings for surgical options. Given the vast range of optical and surgical options available for presbyopia understanding the patient’s visual and lifestyle needs is important to result in the best recommendations. Good product/lens design knowledge and keeping pace with new offerings is important to ensure the most suitable options are discussed.

These management solutions do not cure presbyopia and can come with frustrations, for example the steaming up of spectacle lenses, breaking/losing eyewear or the inconvenience of having to use a near optical correction. There is also the potential for activity limitations (figure 6) including reading, writing, seeing digital screens, recognising faces up close, cooking, needlework, applying makeup and cutting finger/toenails. The increasing difficulty performing close tasks has been linked with the amount of presbyopia. In some cases, hobbies may be ceased or engaged with less enthusiasm due to the near visual challenges.

However, coping strategies include increasing font size, use of spectacles/contact lenses, holding near material at a different distance – the ‘trombone effect’, squinting when reading, use of additional lighting or simply relying on others.

Figure 6: Examples of difficulties with everyday activities for those with presbyopia

Psychological and health impact

The consequences of presbyopia differ between individuals, for some it is one of the first realisations of getting to a certain age milestone and can generate emotional responses such as feeling self-conscious, old, denial, embarrassment, anger, insecurity, low sense of accomplishment or fear of presbyopia progression.

To measure the psychological impact of a disease researchers often use a ‘time trade-off’ concept, where those with the disease are asked how many years of their lifetime, they would sacrifice to be free of the condition. For presbyopia the outcomes were similar to distance vision impairment and hypertension.

Presbyopia has been associated with depression and anxiety. Medications often taken as part of treatment plans for these conditions have the potential to induce issues with accommodative functionality. If the person becomes more socially reclusive, develops unhealthy habits and decreases fitness related activities this could elicit physical as well as mental health issues.

The risk of falls is higher in those over 65 years old (30-40% may fall once a year) meaning careful consideration of the best eyewear solutions with appropriate advice is important.

Financial burdens

An incredible $30bn is the estimated global cost of correcting presbyopia and using the appropriate correction can increase work productivity.7 A study of Indian tea workers showed a 20% increase in work productivity by simply providing near vision spectacles. Sub-optimal correction has been found to lead to a greater than two-fold increase in near task difficulty and having the most beneficial correction option for the individual’s needs is linked to increased productivity-adjusted life years.

There are financial implications to the individuals, society and employers. For those with presbyopia the cost of purchasing eye care services/products could result in a low personal spend of somewhere in the region of US $5 every three years (if favouring off-the-shelf reading spectacles without any eye services) to more than a whopping US $4,000 per year (for those investing in multiple options including surgery and the associated eye appointment costs). Most are likely to spend somewhere on this spectrum, with most of the cost dependant on the frames/lenses/contact lenses selected. Additional costs may come from investing in better lighting and spectacle cleaning products.

Unfortunately for some access to eye care or/and the costs result in trying to cope with out the best correction for their presbyopia especially in low-income areas.

While the benefits of presbyopia correction are generally appreciated, there are plenty of patients who willingly share their annoyances in the workplace of needing to borrow a colleague’s spectacles to better conduct near tasks or the temporary hindering of performance during the adaption period to new eyewear. If fatigue or symptoms results this could lead to time off work, mistakes, avoiding near vision tasks or the perception that this could influence their chances for future career opportunities.

Employers may have increased costs in supporting employees, for example when supplying presbyopia specific safety eye wear, from loss of productivity and when covering periods of absence. A data modelling study estimated that the potential productivity loss related to a lack of correction for presbyopia could be $25.4bn or 0.037% of the global gross domestic product.8 The risk of work-related injuries have also been reported to be higher in those with presbyopia, one study found older welders were 4.2 times more likely to have an ocular injury than those younger ‘free of presbyopia’ welders.

For occupations where minimum near visual standards have been recommended these are frequently not met – one study of dentists found most (93.5%) dentists likely to have presbyopia (45 years old and above) did not achieve the minimum recommended near vision work requirements.

Summary

Presbyopia is common and the numbers are growing, luckily it is easily managed with optical and/or refractive surgery, although using these solutions can come with frustrations and inconveniences. There is a need for a universally agreed definition (which the BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia publications now provides) and by standardising future research approaches will enable for better comparisons of the literature.

As eye care professionals (ECPs), we have an important role in supporting those with presbyopia and addressing the lack of awareness or in some cases denial. We should be empathic as to how presbyopia may mentally and financially impact an individual and adapt our communication style accordingly. Uncorrected/sub-optimal correction of presbyopia can result in a substantial burden, reduced quality of life and productivity, which impacts the individual, society and economy.

A proactive approach will help with identifying risk factors and signs including those approaching presbyopia. For example, a 35-plus years old with asthenopia during prolonged near vision on digital devices may present earlier than typically expected or those taking certain medications that reduce accommodation ability.

A comprehensive history, clinical assessment and visual task analysis is key to ensuring management discussions best match the patient’s needs. Most likely several eyewear options will provide the best outcomes and often the reason given by patients for not having certain presbyopia solutions (for example contact lenses) is the lack of recommendation by the ECP.9 The preferred choices will change with time in line with the evolving demands of the patient, with introduction of new technology/products and simply reflecting that presbyopia is not a static condition. Discussions should include relevant supplementary advice on aspects including work ergonomics and the benefits of lighting.

Presbyopia and age-associated changes are likely to be contributing factors to wider issues including health conditions and through regular eye screening we can help detect red flags and make a significant difference to our patients’ lives.

- Neil Retallic is an optometrist with experience working in practice, education, industry and head office roles. He currently works as the head of professional development at Specsavers and as an assessor and examiner for the College of Optometrists. He is a past president of the BCLA and a member of the GOC Education Committee. He is completing a PhD with the University of Bradford, focusing on the mental welfare status within the optical profession.

- Acknowledgement and recognition to the authors of the original paper-Maria Markoulli, Timothy Fricke, Anitha Arvind, Kevin Frick, Kerryn Hart, Mahesh Joshi, Himal Kandel, Antonio Macedo, Dimitra Makrynioti, Neil Retallic, Nery Garcia-Porta, Gauri Shrestha and James Wolffsohn. The full report can be accessed at BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Epidemiology and impact - Contact Lens and Anterior Eye (contactlensjournal.com).

- This initiative was facilitated by the BCLA, with financial support by way of educational grants provided by Alcon, Bausch + Lomb, CooperVision, EssilorLuxottica, and Johnson & Johnson Vision. The editors for this article series are Neil Retallic and Dr Debarun Dutta.

- The full report can be accessed at BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Epidemiology and impact in the Contact Lens and Anterior Eye journal, available at: contactlensjournal.com, or by following the QR code:

References

- WHO. Ageing and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- Markoulli M, Fricke TR, Arvind A, et al. BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Epidemiology and impact. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Apr 8 2024:102157. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2024.102157

- Wolffsohn JS, Naroo SA, Bullimore MA, et al. BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Definitions. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Apr 11 2024:102155. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2024.102155

- Fricke TR, Tahhan N, Resnikoff S, et al. Global Prevalence of Presbyopia and Vision Impairment from Uncorrected Presbyopia: Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Modelling. Ophthalmology. Oct 2018;125(10):1492-1499. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.04.013

- Bourne RRA, Cicinelli MV, Sedighi T, et al. Effective refractive error coverage in adults aged 50 years and older: estimates from population-based surveys in 61 countries. Lancet Glob Health. Dec 2022;10(12):e1754-e1763. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(22)00433-8

- Li Y, Tan Y, Zhao Z. Impacts of aging on circadian rhythm and related sleep disorders. Biosystems. Feb 2024;236:105111. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2023.105111

- Donaldson KE. The Economic Impact of Presbyopia. J Refract Surg. Jun 2021;37(S1):S17-s19. doi:10.3928/1081597x-20210408-03

- Frick KD, Joy SM, Wilson DA, Naidoo KS, Holden BA. The Global Burden of Potential Productivity Loss from Uncorrected Presbyopia. Ophthalmology. Aug 2015;122(8):1706-10. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.04.014

- Naroo SA, Nagra M, Retallic N. Exploring contact lens opportunities for patients above the age of 40 years. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Dec 2022;45(6):101599. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2022.101599