Domains and learning outcomes (C110400)

• One distance learning CPD point for optometrists and dispensing opticians.

• Communication

(1.5) After successful completion of this CPD practitioners will identify the importance of a patient centred approach for patients living with dementia considering individual patients needs and preferences.

(2.3) After successful completion of this CPD practitioners will recognise the common symptoms of dementia that could indicate a lack of understanding or consent.

• Clinical practice

(5.3) After successful completion of this CPD practitioners be able to recognise the different types of dementia, including posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) visual dementia and apply this to their clinical practice.

Around the world, people are living longer. This increase in the ageing population is accompanied by an increase in the prevalence of dementia, which, while it is not an age-related disease, does affect many older people. This means the numbers of people with dementia seeking help in ophthalmic practice, not only for simple refractive error but also for age-related ocular pathologies, will increase.

Evidence is emerging to suggest that having well-corrected vision (and hearing) can improve the quality of life and independence of people living with dementia (PwD). Several studies have identified that sensory impairment and dementia can be experienced both separately and together, which can prove challenging for both PwD and carers.

Unfortunately, PwD do not always realise they have, or are developing, a sensory impairment. The converse is also true in that someone who has a sensory impairment may not realise they are experiencing the onset of dementia.1

There are an estimated 982,000 people in the UK who are living with a dementia diagnosis.2 One in 14 people in the UK over the age of 65 years have a dementia diagnosis3 and 65% of the people in the UK living with dementia are women.4

Dementia is also the leading cause of death in women since 2011.5 Many patients seen in optometric practice will not have a formal diagnosis and may not realise that anything is wrong, putting symptoms down to getting old.

According to Alzheimer’s Research UK, approximately 40% of people aged 65 years and over, who are thought to be living with a dementia, do not have a formal diagnosis and so do not appear in the official statistics.6

Some people may realise that something is wrong but choose to ignore it for fear of the stigma connected to a dementia diagnosis. Eye care professionals (ECPs) have regular contact with patients and are in a privileged position to support them whether they have an official diagnosis or if they could benefit from further investigation.

This three part series will help ECPs better understand the condition and recognise ways in which they can impact the trajectory of the disease and improve the quality of life of their patients

What is Dementia?

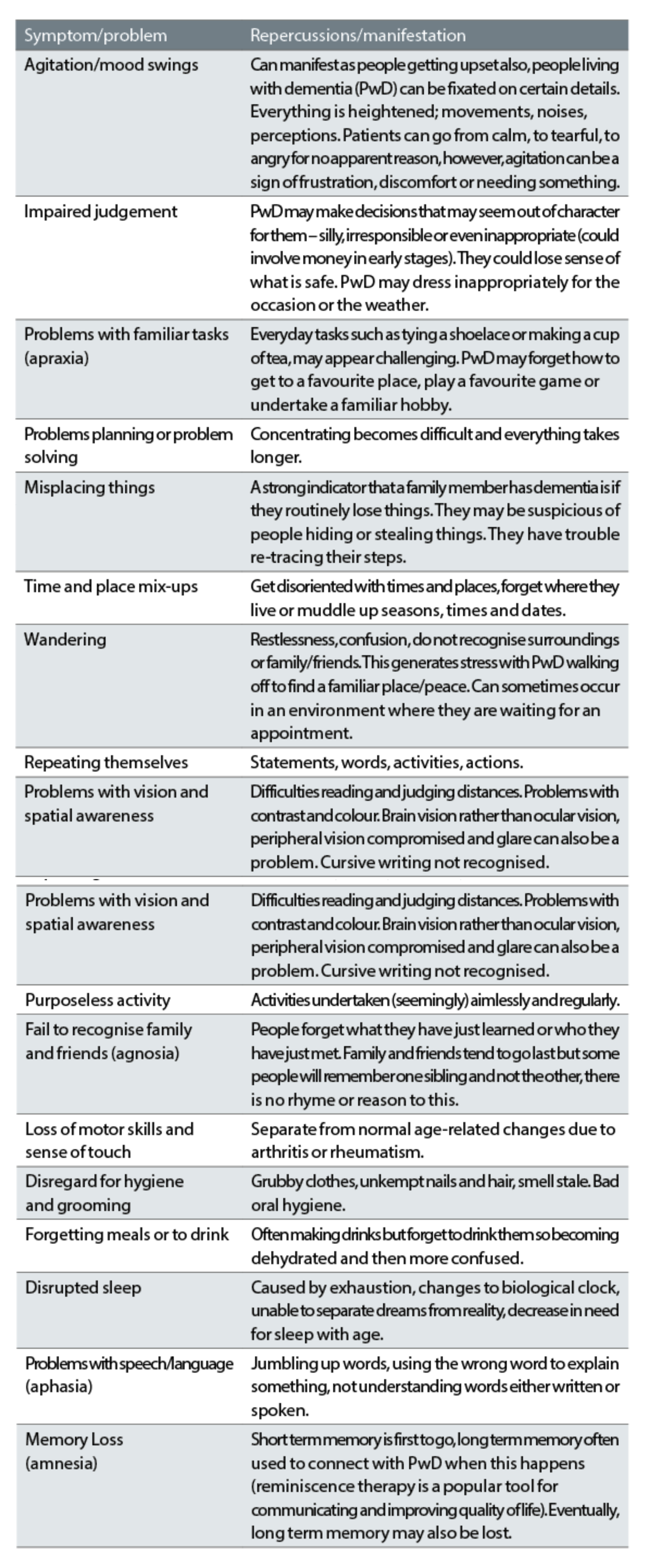

Dementia is an umbrella term for different diseases that result in a loss of cognitive function, leading to a breakdown of everyday thinking skills and sometimes memory.7 The loss in brain function usually happens later in life for a variety of reasons, although it is not classed as age-related.8 It is a progressive and terminal condition, meaning that it will steadily get worse until the patient dies. Dementia can become severe enough to affect everyday life of the person living with the condition. Table 1 highlights some common symptoms of dementia.

Table 1: Common symptoms of dementia

It is important to remember that although we are probably familiar with three main types of dementia: Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and mixed dementia, there are in fact over 100 different variants of dementia.9

Dementia also does not affect everyone in the same way, so the dementia experience is unique for everyone. One of the most important things that ECPs can do is to look beyond the label that a dementia diagnosis gives a patient, look at the person and engage in person-centred care.10

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease accounts for 62% of dementia cases making it the most common form.9 In Alzheimer’s disease, there is a build-up of two forms of protein known as amyloid and tau, which combine to form abnormal clumps in the brain. This bonding process leads to the formation of tiny tangles and plaques which inhibit the brain from functioning properly. The build-up of these structures can lead to brain shrinkage and starve the brain of electrical activity and the formation of chemicals needed for transmission of vital neurological signals.11 The hippocampus (part of the brain used in spatial navigation and memory) has been shown to be at the origin of the amyloid protein build-up.

As the disease progresses and the protein builds up, it then spreads to other parts of the brain.9 As the brain is compromised, symptoms such as memory loss start to appear. People living with Alzheimer’s disease regularly forget recent events, names and faces. They repeat themselves, get confused about dates and times and can get lost, especially in familiar places. The hypothesis of tangles of protein clumps has led researchers to think that removing amyloid protein from the brain may be a way to stop or slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

Figure 1: Confusion with simple tasks

Vascular Dementia

Vascular dementia represents 17% of dementias9 with age considered to be the biggest risk factor, the chances of developing the disease increase sharply after the age of 65 and doubling every five years.12 There are several different types of vascular dementia but this type of dementia is generally caused by a lack of blood flow to the brain, starving it of oxygen, leading to death of brain cells.

Damage can be different in different people, affecting diverse parts of the brain and impacting on many everyday activities. Multi-infarct vascular dementia is caused by a series of mini-strokes including transient ischaemic attacks (TIA), which may be imperceptible.

Another type of vascular dementia is known as subcortical vascular dementia (SVD), which is the most common form. If oxygen and nutrients cannot pass through the vessels due to damage, then the brain tissue becomes compromised. In SVD, blood vessels lying deep in the brain harden and distort due to thickening of cell walls, making it difficult for blood to pass through them. Damage in SVD occurs slowly with damage occurring in the sub-cortex of the brain.

Vascular dementia is commonly triggered by cardiovascular disease but diabetes and stroke also contribute to its onset. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle is important in the prevention of vascular dementia and in many ways, it is a dementia that can be prevented.

A person’s risk is increased with unhealthy lifestyle choices such as smoking, not exercising, eating unhealthy foods and drinking alcohol. People living with vascular dementia often display depression and loss of interest in everyday activities. They may have difficulties with mobility and experience feelings of disorientation. Their thinking becomes slower.9

Figure 2: Dangers of crossing a busy road with visual dementia

Mixed Dementia

Mixed dementia is known to account for 10% of all dementia cases and as the name suggests, it is possible to have more than one type of dementia.

Behavioural changes in Dementia

The front of the brain is responsible for behaviour and social skills. Memory can also be affected when the front of the brain is damaged but is usually okay for some time. Personality changes can be subtle and partners often do not realise straight away, only after progression. It is common to hear people say that they do not recognise their partner anymore or that their loved one has changed. This is known as behavioural variant fronto-temporal dementia (BvFTD) and it is often a sign that is overlooked by families, putting it down to old age.

Visual dementia

The back of the brain (occipital and parietal cortices) is responsible for vision and locating objects in space. Dementia-related visual impairment can occur when the back of the brain is compromised, the most common type being posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) or visual dementia. A definition from Crutch et al (2012) states that PCA is: ‘A progressive neuro-degenerative syndrome that is characterised by higher order visual dysfunction with initial relative sparing of memory and other cognitive functions’.13

People with PCA will display more shrinkage in the back of the brain and this can cause difficulties with more complex tasks such as driving, judging distances or reading.9 People with PCA, may have dyslexia-like symptoms such as difficulties with words jumping or finding the right place on a line of text.

Other skills that rely on the back of the brain, such as spelling and calculating, may be affected early in the disease trajectory. Some people have reported that their world appears fragmented like looking at oneself in a broken mirror. They have difficulty identifying things because they have to piece the scene together like a jigsaw. This can be quite disconcerting for people with the condition and in some cases dangerous, such as when trying to cross a busy road, which appears fragmented and distorted.

Some people report colour vision anomalies such as colour washes in the field of vision and coloured after images. Vision and the importance of correcting visual impairment will be explored in more detail in part two of this series.

Understanding and being understanding: becoming mindful of pre-conceived ideas

A common perception about someone living with dementia is that they are someone who is vacant and not engaged with the world around them. While this may be true with some dementias in advanced stages, most people living with dementia attending for an eye examination will have capacity and will be able to give consent thus, far from the negative stereotype.14

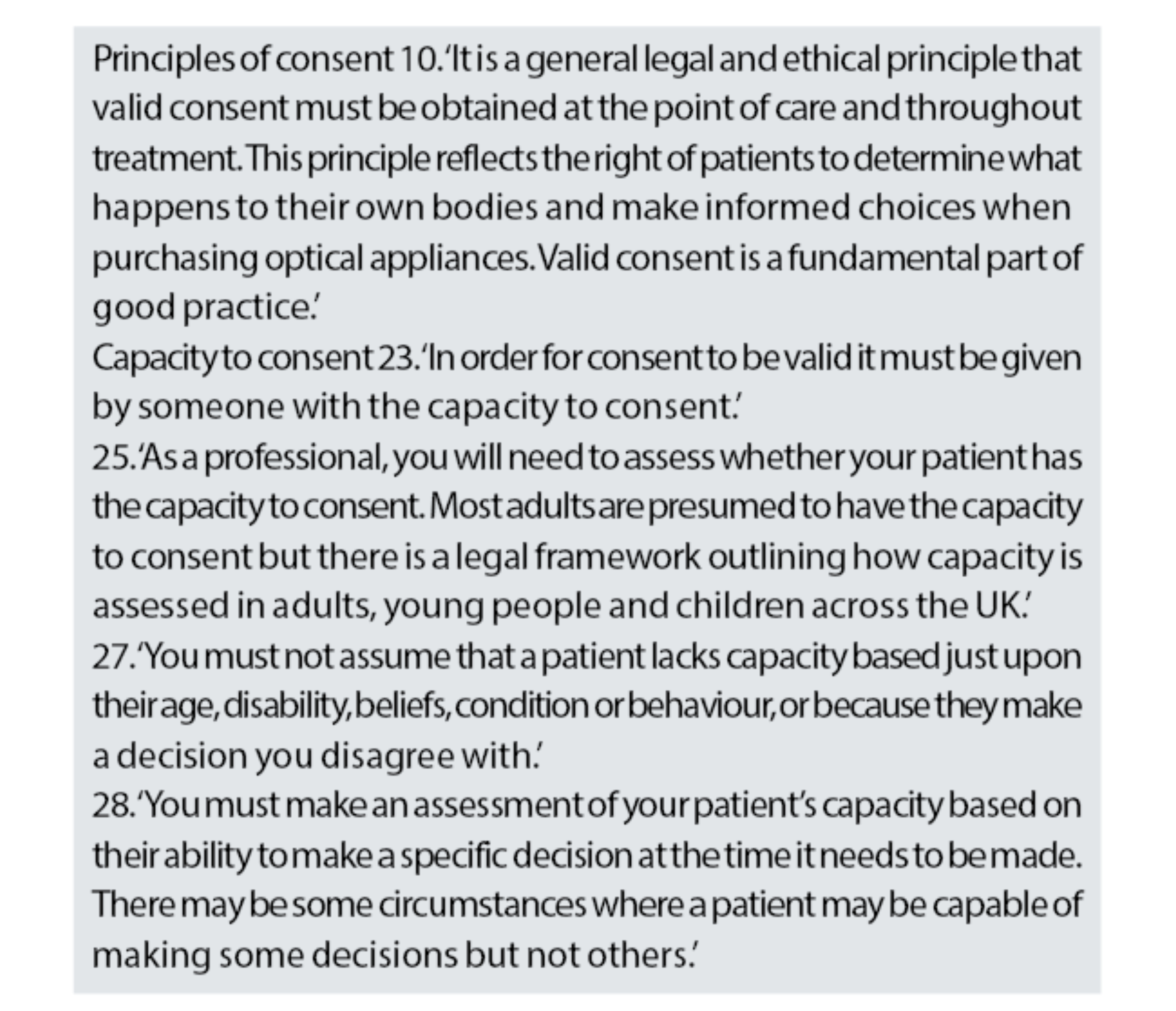

The General Optical Council (GOC) has clear guidance on consent,15 see table 2. Optometrists and dispensing opticians need to assess whether a patient has capacity to consent remembering that people over the age of 16 years are presumed to have capacity to consent. The College of Optometrists also provides guidance on consent.16

Many people are subconsciously influenced about what dementia is, and it is the author’s experience of facilitating CPD sessions, this also holds true for some ECPs. This is why it is important to question our assumptions about dementia by opening up a dialogue about the condition.

Dementia has been considered a taboo topic, probably as it touches on mental health and end of life but people are now becoming more open about mental health issues and dialogue is improving.17 Therefore, conversations about related topics such as dementia should be easier.

Table 2: General Optical Council Supplementary Guidance on Consent15

The way we talk about dementia matters

Despite communication channels opening, dementia has a negative press: 49% of people believe they will be mistaken as crazy (tying in with the taboo theory)18 and 62% felt it meant ‘life is over’ (death, dying and suffering are all emotive subjects).9 In the UK, 57% of over 65-year-olds fear dementia over all other health conditions.19

Ideas pertaining to dementia are often built on hearsay, rather than interaction or discussion with people that have a lived experience. Language has been shown to have a particular impact on people living with dementia. Feeling uncomfortable or uneasy about the condition can occur if there is no first-hand experience due to outside influences such as written or spoken language.

By understanding this, it is easier to make changes and to help our patients to live well for longer. Language used in describing dementia has a role to play conceptualising and influencing a person’s sense of self.20 Language, written or spoken, always has an impact with many derogatory terms being identified as influencing an individual’s self-perception leading people living with dementia to hide their diagnosis.21 In practice, PwD could hide their diagnosis from healthcare professionals.

By communicating about dementia using appropriate words and inflections, narratives can be shaped about living well, adding more humanity and less despair to a diagnosis. Negative language can lead to ‘social death’ and exclusion, with PwD risking alienation from society.22 Using appropriate language saying ‘living with dementia’ rather than ‘suffering from dementia’ becomes immediately more positive.

Popular culture is often guilty of procuring stigma around dementia, whether through literature, film or the news, this negative language and images are known to create social distance between PwD and those without the condition.

Several media stereotypes of dementia use language and images suggesting PwD are inactive due to impairment or age, with no quality of life so unfortunately leading to this common perception.23, 24

Low and Purwaningrum (2020),25 studied books and films pertaining to dementia, finding many stories with negative narratives, such as decline, death and institutionalisation. The press also often depicts dementia as bigger than the person, overwhelming PwD who then feel that there is no way out.26

Alzheimer’s (often mistaken for dementia) is marketed in the media as debilitating, demeaning and desperate.27 Phrases like, ‘condition for which there is no cure’, ‘nothing can be done’, immediately eliminate any sense of hope or notion of maintaining quality of life. The weight of negative outside reactions, can lead to PwD becoming defined by their dementia diagnosis and losing their identity. Relegating dementia into the ranks of terminal disease, fuels fears about developing dementia. As this series of articles continues it will highlight how ECPs play a key role in providing much needed hope to PwD and how they can improve their quality of life.

Many people are too scared of a dementia diagnosis to follow-up any symptoms, thereby delaying seeking help.28 Globally, the non-disclosure rate is estimated to be around 40%. The most common reason medics give being the emotional distress their words may cause.29

The effect of not having these discussions whether due to hesitance on the part of the person living with the condition or the healthcare professional, is that the PwD are denied the chance of making key decisions regarding their future,30 putting their affairs in order,31 thinking of how they wish treatment to be administered in the later stages,32 or even if they wish to take drugs to improve their quality of life.30

In the author’s research into language and stigma, the work of Susan Behuniak (2011)33 stood out exposing inflammatory violent language and unsavoury graphic images. Language treating PwD as ‘already dead’ or ‘walking corpses’ (despite obvious signs of life) leads to them being pitied and feared.34 The risk is that this fear and pity find their way into ophthalmic practice or domiciliary care in a subconscious, non-intentional way.

Scholl and Sabat (2008)35 highlight that emotional responses such as disgust and fear position PwD as ‘others’, outcast from society. Butchard and Kinderman (2018)20 state that dehumanisation, from emotive, terrifying descriptions, make PwD less worthy of compassion than others.

Dementia is often written about in terms of a natural catastrophe with an increase in words depicting dementia as a force of nature threatening to overpower everyone.36 Epidemic language suggests PwD can pass on the condition like a plague, inferring they should be avoided. This is worth noting, since many PwD talk of being lonely and feeling isolated.37

A problem faced by dementia charities is that dementia is associated with ageing and the stigma from ageist language adds to their disability,38 despite dementia not being classified as an age-related condition makes it even more unfair. Then adding mental health further stigmatises the older person39 creating a knock-on effect where assumptions are made about people in the form of negative stereotypes.

The direct impact of ageist propaganda leads to poor quality care, being excluded by society and neglect.40 Being old and discriminated against can lead to feelings of desperation, loneliness and worthlessness affecting the older person’s wellbeing. Quality of life in terms of access to services and inclusion can also be affected.41

Changing the narrative by learning from people with dementia

Many advocates have come forward to document their personal experiences and viewpoints and some advocates make up the Dementia Advisory Board at the University of Hull. This helps people who do not have the condition to ‘walk in their shoes’, better understanding the consequences of negative words and actions.

A recent study looked at the reactions of PwD to the language used describing behaviour changes and some language was found offensive and disrespectful of human rights.42 Language, especially that which implies PwD are difficult or obstructive, was deemed unacceptable. The authors’ recommended knowing the reality and experiences of PwD was the only way to destigmatise the condition and communicate what language is appropriate.43

Figure 3: See the person not the condition

Speaking the truth about dementia through personal experience

Peter Berry: Peter Berry, enjoys life riding his bike, sharing his words – transferring his voice to paper in the form of poetry. Via interviews, he urges people to not talk about PwD but to PwD.44 He uses positive language about living with dementia, such as ‘inspiring’, ‘adapting’, ‘different’.

Keith Oliver: Eloquence and advocacy come from ex-primary headmaster Keith Oliver, who was diagnosed aged 55, while at the top of a career he loved. He carried on in his leadership role until he felt his standards starting to slip. This is when he decided to use his communication skills and real-life experiences to help others.45, 46

Kate Swaffer: Kate Swaffer talks passionately about her diagnosis, how she is outraged at some of the language used and misconceptions generated, and how she plans to further awareness and research.47

As ECPs we can all learn from engaging with the writings of many PwD, discovering personal journeys and understanding their evolving views about dementia as the condition progresses over time.48

Why we should be interested

More than half of adults in the UK (53%) are reported to know someone with dementia. This may be a family member or a friend, or in the case of ECPs, this is more likely to be a patient.19 Dementia is progressive and prevalence of dementia has been found to increase dramatically with age; 1.7% of people aged between 55 and 69 affected compared to >40% of people aged 95 and over.49 Optometrists and ophthalmologists report seeing a large number of people aged >65 years old for eye examinations.50

The worldwide population of people aged 60 years and over is predicted to double by 2050.51 This population increase, coupled with the increasing prevalence of dementia suggests that the >60 demographic, seeking eye care services in the future, risks being affected by this shift.

The majority of care for PwD comes from family members, benefitting people living with dementia but also society.52 Also, 70% of PwD are reported to be living at home with care often falling to the female family member although, all family members will in some way be affected. Optics is a female-dominated profession, which raises the question of the impact on our profession.

A recent publication from the Lancet Commission53 identified uncorrected refractive error as a modifiable risk factor for dementia. This means that ECPs have an important role to play in informing patients of the benefits of regular eye examinations in later life, as well as improving outcomes for patients who may already have a dementia diagnosis. In part two of this series we will look at what research tells us about the role of good vision in dementia prevention and the role of the ECP in improving quality of life for PwD.

Conclusion

Both dementia and visual impairment are associated with senior citizens, a population who are linked to a variety of ocular conditions such as glaucoma, cataract, macular degeneration and simple refractive error, which lead to visual impairment in older people. Many of these eye care anomalies can be avoided, managed or treated if caught early through an eye examination highlighting the role of ECPs.

Every person living with dementia is different. Dementia affects people in a multitude of different ways and our patients will be at different points on their dementia journey. Sitting down with them and getting to know about them as people rather than a condition, discovering their needs and how their quality of life can be improved is key. Understanding how individuals may have been pre-programmed to think in a certain way about dementia and learning to change the narrative, will help ECPs better serve this growing population in the future.

- Elaine Grisdale is the scientific director of the Silmo Academy and director of development for the International Opticians’ Association. She holds a Masters degree in dementia and a First Class Honours degree in vision science. Grisdale was head of professional services and international development at ABDO for over 16 years and before that international professional relations manager for Essilor International and co-director and founder of the successful Varilux University in Paris. She is a liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers, a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and a fellow of the European Academy of Optometry and Optics. She also sits on the executive board of the European Council of Optometry and Optics and serves as secretary for ECOO’s Public Affairs and Economic Committee

References

- Aldridge, A and Newsome, S. Dementia and Sensory Impairment. Journal of Community Nursing. 2022; 36(3), pp56.

- Carnall Farrar. The Economic Impact of Dementia; Module 1 The Annual Cost of Dementia. May 2024. Available at: https://www.carnallfarrar.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Alz-report.pdf

- Wittenberg, R, Hu, B, Barraza-Araiza, L, Rehill, A. Projections of Older People Living with Dementia and Costs of Dementia Care in the United Kingdom, 2019–2040. London: Care Policy and Evaluation Centre, London School of Economics and Political Science. 2019 Nov;79.

- World Health Organisation. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia. September 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033245

- Alzheimer’s Research UK. The Impact of Dementia on Women (How Women are Disproportionately Affected Across Their Lives and What Needs to Change). May 2022.

- Azheimer’s Research UK, Dementia Statistics Hub. 2024. Available at: https://dementiastatistics.org/about-dementia/diagnosis/

- Alzheimer’s Association, What Is Dementia? 2021. Available at: https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia

- LoGuidice, D and Watson, R. Dementia in Older People: an Update. Internal Medicine Journal. 2014; 44, pp.1066-1073.

- Futurelearn. The Many Faces of Dementia [UCL]. 2018; Available at: https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/dementia-care

- Kitwood, T. Towards a Theory of Dementia Care: Ethics and Interaction. Journal of Clinical Ethics. 1998; 9(1), pp.23-34. Available at: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abd/10.1086/JCE199809103?journalCode=jce

- Alzheimer’s Society. Alzheimer’s Disease. 2024; Available at: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/types-dementia/alzheimers-disease

- Alzheimer’s Society. Vascular Dementia. 2024; Available at: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/types-dementia/vascular-dementia

- Crutch, SJ, Lehmann, M, Schott, JM, Rabinovici, GD, Rossor, MN, Fox, NC. Posterior Cortical Atrophy. The Lancet Neurology. 2012 Feb 1;11(2):170-8. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S1474-4422%2811%2970289-7

- Shah,R, Edgar,DF, Bowen, M, Hancock, B. Dementia and Optometry: A Growing Need. Optometry in Practice. 2017;18(4):177-86. Available at: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/19275/1/

- General Optical Council. Supplementary Guidance on Consent. Available from: https://optical.org/media/4dibfi3g/supplementary-guidance-on-consent.pdf [Accessed 25th November 2024]

- College of Optometrist. Consent, Capacity to consent - adults. Available from: https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/guidance/communication,-partnership-and-teamwork/consent/capacity-to-consent-%E2%80%93-adults [Accessed 25th November 2024

- Gillespie, L. Talking About My Generations. Occupational Health & Wellbeing. 2020; Volume 72, no. 4, pp. 24-25.

- Alzheimer’s Society. Over Half of People Fear Dementia Diagnosis, 62 Per Cent Think it Means ‘Life is Over’. 2024. Available at: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/news/2018-05-29/over-half-people-fear-dementia-diagnosis-62-cent-think-it-means-life-over

- Alzheimer’s Research UK. Dementia Attitudes Monitor. November 2023. Available at: https://dementiastatistics.org/attitudes/Dementia%20Attitudes%20Monitor%20-%20Wave%203%20report.pdf

- Butchard, S and Kinderman, P. Human Rights, Dementia and Identity. European Psychologist. 2019; 24(2), 159-168.

- Alzheimer’s Society. Positive Language: An Alzheimer’s Society Guide to Talking About Dementia. 2022. Available at: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-09/Positive%20language%20guide_0.pdf

- George, DR. Overcoming the Social Death of Dementia Through Language. The Lancet. 2010; 376(9741), pp. 586-587.

- Gerritsen, DL, Oyebode, J, Gove, D. Ethical Implications of the Perception and Portrayal of Dementia. Dementia. 2018; 17(5): 596-608

- Ballenger, JF. Framing Confusion: Dementia, Society and History. AMA J. Ethics. 2017; 19(7): 713-9.

- Low, LF and Purwaningrum, F. Negative Stereotypes, Fear and Social Distance: A Systematic Review of Depictions of Dementia in Popular Culture in the Context of Stigma. BMC Geriatrics. 2020; 20:477.

- Brookes, G, Harvey, K, Chadborn, N, and Dening, T. “Our Biggest Killer”: Multimodal Discourse Representations of Dementia in the British Press. Social Semiotics. 2018; 28(3), pp. 371-395.

- Jolley, DJ and Benbow, SH. Stigma and Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes, Consequences and a Constructive Approach. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2000; 54, 2, 117-9.

- Bond, J, Stave, C, Sganga, A, Vincenzo, O, O’Connell, B, Stanley, RL. Inequalities in Dementia Care Across Europe: Key Findings of the Facing Dementia Survey. Int. J. Clin. Pract.. 2005; 59 (s146), 8-14.

- Bamford, SM. Dementia: The Challenge and Importance of Diagnosis in Europe. Br. J. Neurosci. Nurs.. 2010; 6(3);110.

- Mitchell, G. Applying Pharmacology to Practice: The Case of Dementia. Nurse Prescrib.. 2013;11(4): 185-90.

- Milne, A. The ‘D’ Word: Reflections on the Relationship Between Stigma, Discrimination and Dementia. Journal of Mental Health. 2010; 19, 227-233.

- Woods, B. and Pratt, R. Awareness in Dementia: Ethical and Legal Issues in Relation to People with Dementia. Ageing Mental Health. 2005; 9(5), 423-9.

- Behuniak, S. The Living Dead? The Construction of People with Alzheimer’s Disease as Zombies. Ageing and Society. 2011; 31, 70-92.

- Aquilina, C, and Hughes, JC. The Return of the Living Dead: Agency Lost and Found? In Hughes, JC, Louw, SJ and Sabat, SR. (eds) Dementia: Mind, Meaning and the Person. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2006; 143-161.

- Scholl, JM and Sabat, SR. Stereotypes, Stereotype Threat and Ageing: Implications for the Understanding and Treatment of People with Alzheimer’s Disease, Ageing and Society. 2008; 28, 103-130.

- Zeilig, H. Dementia as a Culture Metaphor. Gerontologist. 2014; 54(2), 258-67.

- Moyle, W, Kellett, U, Ballantyne, A, Gracia, N. Dementia and Loneliness: An Australian Perspective. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011; 20; 1445-1453.

- Thornicroft, G. Actions Speak Louder…Tackling Discrimination Against People With Mental Health Problems. London: Mental Health Foundation. 2006

- Godfrey, M, Surr, C, Boyle, G, Townsend, G, Brooker, D. Prevention and Service Provision: Mental Health Problems in Later Life. Institute of Health Sciences and Public Health Research, University of Leeds and Division of Dementia Studies, University of Bradford. 2005.

- Victor, C. The Social Context of Aging: A Textbook of Gerontology. Abingdon: Routledge. 2005.

- Age Concern and Mental Health Foundation. Promoting Mental Health and Well Being in Later Life. London: Age Concern. 2006.

- Cahill, S. Dementia and Human Rights. Policy Press. (2018)

- Wolverson, E, Dunn, R, Moniz-Cook, E, Gove, D and Diaz-Ponce, A. Behaviour Changes in Dementia: A Mixed Methods Survey Exploring the Perspectives of People with Dementia. J. Adv. Nurs.. 77: 1992-2001. (2021)

- La Bey, L. Peter Berry - Living Graciously When Diagnosed With Dementia. 2018. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0e-u0XU3g28

- Oliver, K. Dear Alzheimer’s: A Diary of Living with Dementia. Great Britain: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2019.

- NHS Kent and Medway. Keith Oliver. 2022. Available at: https://www.kmpt.nhs.uk/get-involved/participation-and-involvement/living-with-dementia/dementia-envoys/keith-oliver/

- Swaffer, K. Dementia, Stigma, Language and Dementia-Friendly. United Kingdom; Sage Publications, Sage, UK. 2014.

- Zimmerman, M. Alzheimer’s Disease Metaphors as Mirror and Lens to the Stigma of Dementia. Lit. Med.. 2017; 35(1); 71-97.

- Bowen, M, Edgar, DF, Hancock, B, Haque, S, Shah, R, Buchanan, S, Iliffe, S, Maskell, S, Pickett, J, Taylor, JP, O’Leary, N. The Prevalence of Visual Impairment in People With Dementia (the PrOVIDe Study): a Cross-Sectional Study of People Aged 60-89 Years With Dementia and Qualitative Exploration of Individual, Carer and Professional Perspectives. Health and Delivery Research. 2016; Volume 4, No. 21.

- Kergoat, H, Leat, SJ, Faucher, C, Roy, S, Kergoat, MJ. Primary Eye-Care Services Offered to Older Adults. European Geriatric Medicine. 2015 Jun 1;6, pp. 241-244.

- United Nations. World Population Ageing. 2017. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2017_Highlights.pdf

- World Health Organisation. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia. Geneva: World Health Organisation. 2021. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1962&context=srhreports

- Livingston, G, Huntley, J, Liu, KY, Costafreda, SG, Selbæk, G, Alladi, S, Ames, D, Banerjee, S, Burns, A, Brayne, C, Fox, NC. Dementia Prevention, Intervention and Care: 2024 Report of the Lancet Standing Commission. The Lancet. 2024 Aug 10;404(10452):572-628.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01296-0