Domain and Learning Outcomes (C-110520)

One distance learning CPD point for optometrists and dispensing opticians.

Communication

Upon completion of this CPD, ECPs will be able to identify different tools that may be used to communicate effectively with patients about myopia (s2).

Upon completion of this CPD, ECPs will be able to describe the types of information/misinformation patients may be exposed to including where patients may have undertaken research in advance of the consultation. ECPs will be able to use this information to better explain whether information is not valid or relevant (s1).

Health-related trends can be driven by both traditional and newer forms of media¹. For example, a recent TikTok trend advocates staring at the sun, while more traditional forms of media have recently helped popularise the apparent benefits of yoga eye exercises; both trends offer the promise of perfect vision²,³.

Establishing a direct link between misinformation and impact on health is difficult; however, acting on some of these trends could lead to harm. There are now videos countering the sungazing trend with cautionary tales of solar retinopathy; less overt health risks could include delays in seeking professional care or developing a distrust of healthcare practitioners4.

A report of ophthalmology related TikTok trends concluded that while social media offers opportunities to educate, there is also a risk it promotes life threatening actions2.

Our professional backgrounds in optometry may insulate us against some of the claims made about so-called ‘natural myopia cures,’ but separating fact from fiction poses a greater challenge for patients.

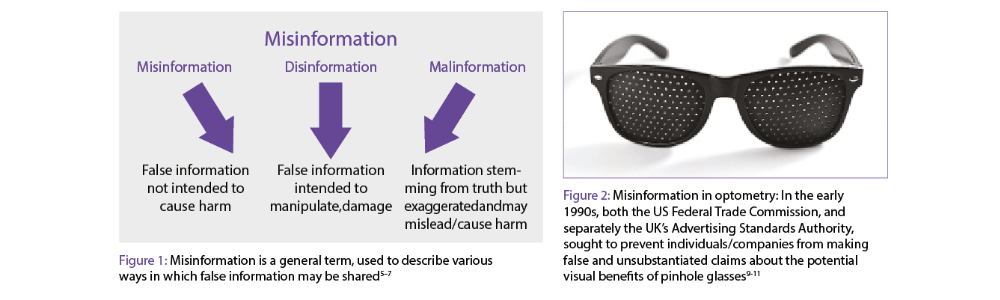

What is misinformation?

‘Misinformation’ is often used as an umbrella term to describe ways through which false information is distributed. The actual definition of misinformation is the sharing of false information without ill intent.

Conversely, it is ‘disinformation’ which describes false information shared with the intention to manipulate, cause damage, or wrongly guide individuals or organisations5-7. Yet, situations are rarely so binary.

In some cases, information may stem from the truth, but will have been exaggerated in such a way that it may mislead or cause harm: this is sometimes referred to as ‘malinformation’6.

Why might misinformation spread?

Misinformation is widespread, which makes avoiding it a challenge. While figures are difficult to estimate, misinformation could account for 0.2-29% of all news consumed, possibly higher in the field of health7. Difficulties in identifying misinformation can further exacerbate matters.

A survey by the UK’s communications regulator, Ofcom, found that while seven in 10 adults reported confidence in identifying misinformation, only around two in 10 were able to identify genuine social media posts without making mistakes8.

Psychological factors, such as pre-existing views or biases, can play a role in susceptibility to misinformation12.

For example, repeated exposure to the same message (or piece of misinformation) increases its believability, and can do so even when the information contradicts an individual’s prior knowledge7; highlighting the need to address misinformation early i.e. before multiple exposures.

Susceptibility to sharing content has been reported to increase if the information portrays the sharer’s ‘opponent’ in a negative manner, i.e. content which supports the sharer’s beliefs or reinforces a particular narrative7.

Researchers also suggest online communities, or ‘echo chambers’, can form, which lead individuals with similar viewpoints to distance themselves from others who disagree with them13. Such communities could reduce exposure to diverse opinions and contribute to the spread of misleading information14.

Other factors which may encourage sharing of content is if the information elicits feelings of anger or outrage. Social media algorithms can track user engagement and prioritise content which elicits strong emotions7.

And, unsurprisingly, individuals are more likely to believe misinformation if it comes from ‘in-group’ sources; individuals they consider to be credible or trustworthy12.

Reinforcement of views and biases

Reasons why individuals may experience a positive effect from some of the less mainstream myopia therapies, such as vision therapy, could include the placebo effect i.e. the individual expects to see a change and so believes there to be one.

Other possible reasons could include the potential memorisation of test charts (where repeated viewing of test charts forms part of the therapy), blur adaptation, and perceptual learning15.

The role of the placebo effect has been demonstrated in various areas of optometry. In a recent study, university students were assigned to experimental conditions in which they were given capsules alleged to confer either a positive effect (placebo), negative effect (nocebo), or exposed to a third condition in which a capsule was not provided (control group).

Accommodative response was found to be more stable with the placebo compared to the nocebo. Better stereoacuity was also found with the placebo compared to the nocebo and control16.

Poor health literacy

Despite some of the flawed logic underlying the sharing of misinformation, perhaps there are other reasons why people feel compelled to turn to social media.

The UK’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) states more than four in 10 adults struggle to understand the health content written for the public and that approximately 7.1 million adults in the UK read at, or below, the levels of an average nine-year-old17.

Additional obstacles to communication may present in the form of language barriers or health conditions that can affect comprehension17.

The NHS suggests that health literacy related problems may account for up to 5% of national health spending. Health literacy can also be linked to health inequality, for example through poorer uptake of preventative health services17, 18.

For some individuals, digital literacy could also present an additional barrier to accessing information and services e.g. problems using online health appointment booking systems19.

So, how well is our messaging about myopia reaching the public?

Public Views of Myopia

Interest in myopia and astigmatism

While there have been many studies providing valuable snapshots of information regarding the public’s views of myopia, most have concentrated on small cohorts or specific populations.

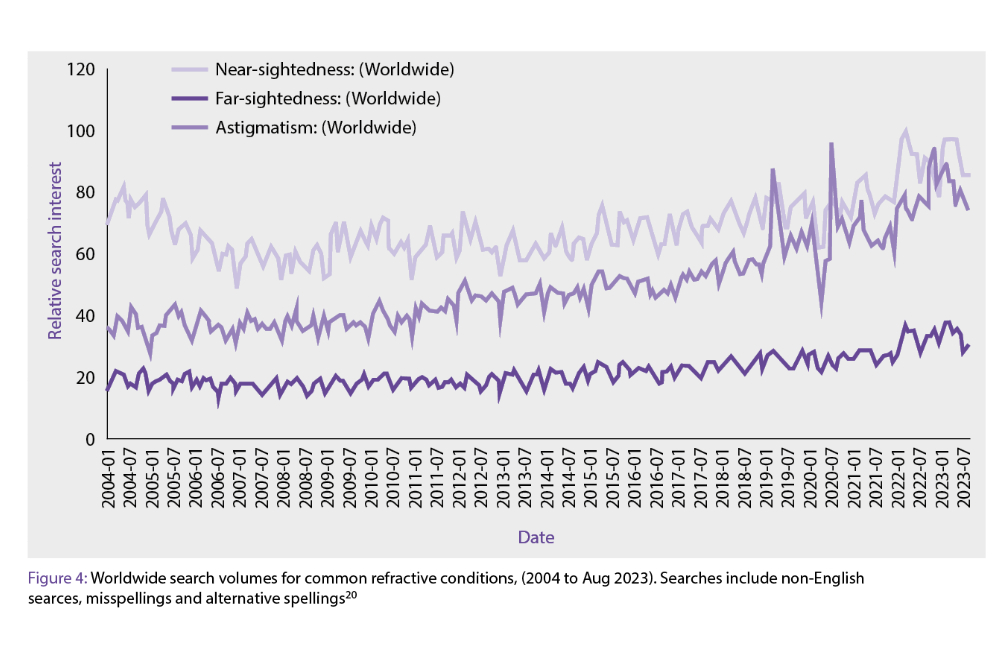

More recently, global Google searches being made for myopia and refractive error related terms were evaluated20. A relative increase in search volume related to myopia was noted, as well as increasing interest in astigmatism.

With respect to interest in myopia control/myopia management, a steep increase in the relative search interest was noted over the past ~eight to nine years. The increase appeared to coincide with the introduction of the recent cohort of myopia management products.

A marked rise in search interest was also noted around 2021. It was speculated that this may be linked to media articles published at the time which had suggested Covid-19 related lockdowns could induce myopia/myopia progression, and thus may have led concerned parents to investigate myopia management options online.

The data also suggested searches were being undertaken for specific myopia management products (including searches for trade names and brands)20. It would seem, therefore, that the rise in marketing efforts and information about myopia is indeed reaching the public. Intriguingly, ‘cost’ was not among the top searches related to myopia management20.

Money matters

While data on the issue of cost and myopia are limited, a study conducted on parental views of myopia in Ireland, reported only around a third (31%) considered myopia an expense21.

Larger proportions viewed myopia as a health risk (46%); an optical inconvenience (46%); and few considered myopia to be a cosmetic inconvenience (14%). More recently, a related topic was studied by a group in Spain22.

The investigators were interested in how concerned parents were about myopia and the reasons underlying their concern. This study also found ocular health and the dependence on correction to be key concerns (80.0% and 37.1% respectively); and concerns about cosmesis and cost were comparatively lower (4% and 13.7% respectively).

While the two examples described above are drawn from two separate studies, with differing experimental approaches, and different cohorts, there is a common indication that cost may not be the primary concern for some parents. For UK based Eye Care Professionals (ECPs), however, it appears finance is the greatest barrier to discussing myopia management.

A recently published study found ECPs were uncomfortable communicating the financial aspects to parents and, perhaps most concerning of all, some ECPs felt discouraged from offering treatment especially to those patients they felt would be unable to afford it23.

Myopia misunderstandings?

Ortiz-Peregrina et al (2023) asked parents for their opinions on the causes or habits that influence the onset or progression of myopia in children. The responses paint a mixed picture with most respondents believing genetics (91.3%) and use of electronic devices (mobile phones, tablets, video-game consoles, etc) (85%) played a major role.

Nutrition was also believed to play a role (32.7%), but aspects which have a stronger evidence base, e.g. studies/education, were ranked lower than might be expected.

The same study identified that the level of concern a parent had about myopia was linked to the parent’s perception of how fast the myopia was increasing and the number of health consequences of myopia on eye health.

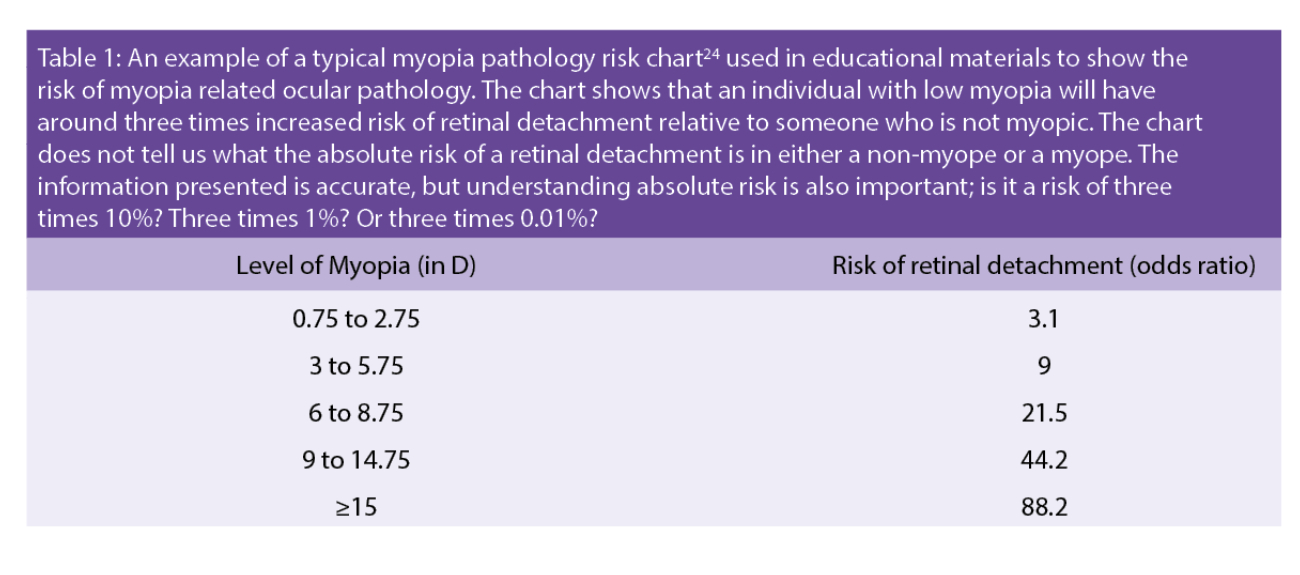

Further analysis showed the ocular health consequence most strongly associated with parental concern was retinal detachment22.

While a higher risk of retinal detachment is linked to greater magnitudes of myopia, it may be worth considering how that risk presented.

The College of Optometrists’ guidance on myopia management makes clear that ‘there is evidence that people with myopia have a relatively small increased absolute risk for ocular complications as a result of myopia’25.

There are many other potential benefits of myopia management, e.g. retaining uncorrected vision at a better level, reduced likelihood of thicker or heavier lenses, less need to pay for thinner lenses, impact on quality of life, or even the possibility of better corneal refractive surgery outcomes25.

Optimising Communication in Myopia

The above lays out some of the challenges with relaying messages about myopia. So, how can communication about myopia be improved? The World Council of Optometry statement on myopia suggests having frequent discussions with parents which cover: the definition of myopia, lifestyle factors impacting myopia, increased risks to long term health, and approaches you may use to manage myopia and slow its progression26.

The College reminds ECPs that patient response to a myopia intervention may not be as expected and that it may take time for this to become apparent. Other discussion points may also include parental/patient time commitments and costs associated with myopia management27.

Making healthcare related changes is challenging.In other fields of healthcare, various behavioural change models have been used as part of healthcare initiatives28; these models suggest different factors may influence behaviour.

For example, an individual might consider the ‘perceived threats’ of a health condition, such as the perceived severity and perceived susceptibility i.e. how likely am I (or my child) to become myopic? What are the negative effects I (or my child) may experience?

An individual may consider the perceived benefits and perceived barriers associated with acting, i.e. weighing up the pros and cons; and an individual’s self-belief that they can make a health-related change, ‘self-efficacy’, may also play a role.

Finally, consideration may be given to triggers that encourage action (‘cues to action’)28, 29, such as reminders to go outside to prevent myopia onset. Factors such as demographics (e.g. age) and psychological characteristics may also exert an influence on health-related behaviours.

Yet, relying on a single appointment to address all the points, without any further reinforcement of messaging, may prove difficult and possibly ineffective.

Regular reminders?

Various elements of a health behaviour model, with respect to myopia, were evaluated in a group of highly myopic university students29. The students responded to a questionnaire to establish their baseline knowledge and feelings about myopia.

This was followed by a single 150 min education session involving a lecture and simulation of several types of myopia related pathologies. Immediately after the education session, the questionnaire was completed a second time, and then run a third time six weeks after the education session.

The results showed that although there was an increased awareness in some elements following the education session, there was no significant effect on others (e.g. perceived benefits, perceived barriers). The authors concluded that for long-term change in behaviour, repeated interventions (education programmes), and goal progress feedback may be required29.

Further support for repeated reminders may be found in the findings of a randomised controlled study, where parents were sent text messages, twice a day, for one year, encouraging them to take their children outdoors.

Researchers found children in the intervention group did experience greater light exposure and time outdoors compared to the control group. Axial elongation and myopia progression were also slower in the text message group.

Although the texts were only sent over one year, the researchers found that axial elongation and myopia progression were slower over three years30.

While the findings are valuable, outside of a research study, it is unclear how many parents would welcome twice daily text messages from their optometrist! However, there are plenty of other resources available to those wishing to improve patient education.

Mobile health apps and online simulation

A wide range of myopia-related apps and online tools are available to parents and patients. Such tools can help parents, and practitioners, calculate a myopia risk profile using different pieces of information such as age, myopia level, parental history.

Some of these tools contain percentile charts which provide a visual representation of how a child’s eye growth compares to other children. Some platforms also include prediction charts of how much a child’s refractive error and/or axial length may change with/without myopia management interventions.

Among the numerous potential benefits of such tools is that they allow easy tracking of myopia progression and axial elongation, helping parents and practitioners develop more comprehensive records which can inform decisions around myopia management options, goal setting, and target monitoring.

Some biometers for axial length measurement also incorporate features such as percentile charts and myopia risk analysis tools.

Use of simulators that show different levels of dioptric blur could also facilitate communication about myopia. For parents who are not myopic, such simulators may provide a better insight into their child’s visual experience.

Wearable technology

To understand the role of light and environmental factors on myopia development and its progression, researchers have used wearable technologies such as light monitors or made use of activity trackers31, 32.

Last year, the tech giant Apple released new vision health features for several of its devices (iPhone, iPad, and Apple Watch). Apple’s press release specifically highlighted aims to encourage healthy behaviours and reduce the risk of myopia33.

Myopia related features include a light sensor which detects the amount of time spent in daylight, a measure of screen distance, and a measure of screen time34. Other simpler technologies such as pedometers/step counters are widely available and estimates of screen time usage are a common feature of electronic screen-based devices.

A ‘gamification’ type approach may prove useful in encouraging changes to health behaviour. In one example, where myopia researchers studied enablers and barriers to children spending time outdoors, children were found to be motivated by incentives (including monetary) related to their step count (measured using a pedometer).

Competitions were also reported between family and friends to see who could achieve the highest number of steps31.

Reputable sources of information

Thanks to the efforts of our professional bodies and wider profession, it is possible for ECPs to find high quality patient information about myopia, making it easier to redirect patients to reputable sources.

For example, the creators of the well-known Myopia Profile website which is aimed at eyecare practitioners35, also run a patient friendly site offering multiple resources including video guides and easy to read articles about myopia36.

The site also includes a myopia risk assessment tool and easy to understand infographics that can be printed and shared with patients.

The NHS recommends potential content creators follow the NHS design principles which can be found here: https://service-manual.nhs.uk/design-system/design-principles38. Some sites, such as the College’s patient information website (https://lookafteryoureyes.org/), carry a Crystal Mark in recognition of their compliance with the Plain English Campaign39, 40.

More formal guidance has also been developed. In 2023, the International Organisation for Standardisation published a plain language guide to facilitate creation of written documentation41.

Multiple tools have also been developed to evaluate the ‘readability’ of written health communications42, 43. Microsoft Word generates both a Flesch Reading Ease score, (using a 100-point scale, a higher score indicates ease of understanding) and generates a Flesch Kincaid grade level to assess for which US school grade the text is most suitable44.

The potential role of artificial intelligence

One of the more intriguing developments of recent years has been the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI). The performance of AI in answering questions about myopia appears to be surprisingly good.

In one study, two versions of ChatGPT (a free version and a paid version), and Google’s AI tool Bard were all considered when answering common myopia related queries45. While the performance of all three tools was impressive, the paid version of ChatGPT was ranked as ‘good’ by experts ~80% of the time.

Such tools could, in future, alleviate the burden on healthcare practitioners. We are already seeing some healthcare providers incorporating AI Chatbots onto their websites.

Stopping Misinformation

Report misinformation

Most social media sites allow individuals to report false or inappropriate content, helping to stop the spread of misinformation. Additional safeguards have also been introduced to help patients select more reputable sources of information.

For example, YouTube, the video sharing platform, has begun using a verification system which makes clear to viewers when the content creator is a registered healthcare professional46.

Content creation

Another way to stop misinformation is through sharing evidence-based corrections i.e. debunking12.

A recent study evaluating myopia information on TikTok found that while videos published by healthcare professionals and non-profit organisations were of high quality, they tended to be less popular47.

Popular myopia videos focussed on outcomes, management of myopia, and risk factors, but videos which were less popular were those longer than 60 seconds duration. While only a few of us may engage in social media content creation, it is worth noting that the same study reported just 219 myopia related videos had received 2.25 million likes and 0.2 million shares.

Few practitioners will reach such large audiences through practice websites alone; it may be worth considering how these newer forms of communication can be incorporated into businesses or how larger optical companies can help by promoting accurate and engaging information on their social media channels.

Clear and engaging information is a good start, but researchers have also stressed the importance of building public trust in health authorities in order to help combat health misinformation48.

Also, since each social media platform appeals to specific demographics, selecting the most appropriate platform may be key to maximising information dissemination.

Improving health literacy

It may be possible to improve health literacy through ‘prebunking’ i.e. education against misinformation before it has occurred. This could be on social media or via alternative approaches such as school-based delivery.

In one example, regular reminders sent to parents about myopia inhibiting habits via an online messaging service were linked to a small decrease in the rate of myopia incidence49, 50; demonstrating the potential of positive messaging.

Conclusion

Unlike the advice received during a single eye examination, social media can offer repeated exposures to information, and present information in different and engaging forms.

There are many ways to harness internet-based resources for positive health communication about myopia. For example, redirecting individuals to reputable sources of information, or towards online tools for parents/patients to use outside of the regular eye examination.

When communicating information about myopia, it may be helpful to both explain the potential risks of myopia but also discuss potential protective behaviours or actions an individual can take.

And finally, even if we may not offer myopia management ourselves, professional guidance encourages ECPs to at least have that initial conversation about myopia.

Acknowledgements

- Hoya Vision Care are gratefully acknowledged for supporting the author in preparing this article.

References

- Kaňková J, Binder A, Matthes J. Health-related communication of social media influencers: A scoping review. Health Commun. 2024 Sep 11;1–14.

- Al Hassan S, Bou Ghannam A, S Saade J. An emerging ophthalmology challenge: A narrative review of TikTok trends impacting eye health among children and adolescents. Ophthalmol Ther. 2024 Apr;13(4):895–902.

- McCarthy-McClean A. Calling out This Morning’s eye yoga segment [Internet]. Optician Online. 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.opticianonline.net/content/news/calling-out-this-morning-s-eye-yoga-segment/

- Borges do Nascimento IJ, Pizarro AB, Almeida JM, Azzopardi-Muscat N, Gonçalves MA, Björklund M, et al. Infodemics and health misinformation: a systematic review of reviews. Bull World Health Organ. 2022 Sep 1;100(9):544–61.

- Disinformation and public health [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/disinformation-and-public-health

- How to identify misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation (ITSAP.00.300) [Internet]. Canadian Centre for Cyber Security. 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.cyber.gc.ca/en/guidance/how-identify-misinformation-disinformation-and-malinformation-itsap00300

- Using psychology to understand and fight health misinformation [Internet]. 2023 Nov [cited 2024 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/health-misinformation

- The genuine article? One in three internet users fail to question misinformation [Internet]. www.ofcom.org.uk. 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/media-use-and-attitudes/attitudes-to-news/one-in-three-internet-users-fail-to-question-misinformation/

- File:Rasterbrille.Jpg [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 17]. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rasterbrille.jpg

- Hicks C. The truth about pinhole glasses. Independent [Internet]. 1997 Jul 28 [cited 2024 Nov 17]; Available from: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/the-truth-about-pinhole-glasses-1253113.html

- Kanclerz P, Khoramnia R, Atchison D. Applications of the pinhole effect in clinical vision science. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2024 Jan 1;50(1):84–94.

- Ecker UKH, Lewandowsky S, Cook J, Schmid P, Fazio LK, Brashier N, et al. The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nat Rev Psychol. 2022 Jan 12;1(1):13–29.

- Törnberg P. Echo chambers and viral misinformation: Modeling fake news as complex contagion. PLoS One. 2018 Sep 20;13(9):e0203958.

- Gao Y, Liu F, Gao L. Echo chamber effects on short video platforms. Sci Rep. 2023 Apr 18;13(1):6282.

- Elliott DB. The Bates method, elixirs, potions and other cures for myopia: how do they work? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2013 Mar;33(2):75–7.

- Vera J, Redondo B, Ocaso E, Martinez-Guillorme S, Molina R, Jiménez R. Manipulating expectancies in optometry practice: Ocular accommodation and stereoacuity are sensitive to placebo and nocebo effects. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2022 Nov;42(6):1390–8.

- Powell M. Health information: are you getting your message across? [Internet]. National Institute for Health Research; 2022 Jun [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/collection/health-information-are-you-getting-your-message-across/

- Health literacy - NHS digital service manual [Internet]. nhs.uk. [cited 2024 Nov 17]. Available from: https://service-manual.nhs.uk/content/health-literacy

- Alturkistani A, Greenfield G, Beaney T, Norton J, Costelloe CE. Cross-sectional analyses of online appointment booking and repeat prescription ordering user characteristics in general practices of England in the years 2018-2020. BMJ Open. 2023 Oct 12;13(10):e068627.

- Nagra M, Wolffsohn JS, Ghorbani-Mojarrad N. Using big data to understand interest in myopia. Optom Vis Sci. 2024 Jan 1;101(1):37–43.

- McCrann S, Flitcroft I, Lalor K, Butler J, Bush A, Loughman J. Parental attitudes to myopia: a key agent of change for myopia control? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2018 May;38(3):298–308.

- Ortiz-Peregrina S, Solano-Molina S, Martino F, Castro-Torres JJ, Jiménez JR. Parental awareness of the implications of myopia and strategies to control its progression: A survey-based study. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2023 Sep;43(5):1145–59.

- Coverdale S, Rountree L, Webber K, Cufflin M, Mallen E, Alderson A, et al. Eyecare practitioner perspectives and attitudes towards myopia and myopia management in the UK. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2024 Jan 11;9(1):e001527.

- Flitcroft DI. The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012 Nov;31(6):622–60.

- Childhood-onset myopia management: Guidance for optometrists [Internet]. The College of Optometrists. [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.college-optometrists.org/category-landing-pages/clinical-topics/myopia/myopia-management-–-guidance-for-optometrists

- Resolution: The Standard of Care for Myopia Management by Optometrists - world council of optometry [Internet]. World Council of Optometry -. World Council of Optometry; 2021 [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://worldcouncilofoptometry.info/resolution-the-standard-of-care-for-myopia-management-by-optometrists/

- [cited 2024 Nov 22]. Available from: https://www.college-optometrists.org/category-landing-pages/clinical-topics/myopia/myopia-management-–-guidance-for-optometrists#PatientsParents

- Hilton CE. Behaviour change, the itchy spot of healthcare quality improvement: How can psychology theory and skills help to scratch the itch? Health Psychol Open. 2023 Jul;10(2):20551029231198936.

- Tseng G-L, Chen C-Y. Evaluation of high myopia complications prevention program in university freshmen. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Oct;95(40):e5093.

- Li S-M, Ran A-R, Kang M-T, Yang X, Ren M-Y, Wei S-F, et al. Effect of text messaging parents of school-aged children on outdoor time to control myopia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2022 Nov 1;176(11):1077–83.

- Drury VB, Saw SM, Finkelstein E, Wong TY, Tay PK. A new community-based outdoor intervention to increase physical activity in Singapore children: findings from focus groups. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013 May;42(5):225–31.

- Harb EN, Sawai ES, Wildsoet CF. Indoor and outdoor human behavior and myopia: an objective and dynamic study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Oct 31;10:1270454.

- Apple. Apple provides powerful insights into new areas of health [Internet]. Apple. 2023 [cited 2024 Nov 22]. Available from: https://www.apple.com/uk/newsroom/2023/06/apple-provides-powerful-insights-into-new-areas-of-health/

- Health [Internet]. Apple (United Kingdom). [cited 2024 Nov 22]. Available from: https://www.apple.com/uk/health/

- Myopia Profile [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.myopiaprofile.com/

- My Kids Vision [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.mykidsvision.org/en-US/

- Understanding myopia with infographics [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.mykidsvision.org/knowledge-centre/understanding-the-myopia-profile-infographic

- [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://service-manual.nhs.uk/design-system/design-principles.

- Soames B. Internet crystal Mark holders [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.plainenglish.co.uk/services/internet-crystal-mark/internet-crystal-mark-holders.html

- Eye health advice & care [Internet]. Look After Your Eyes. 2012 [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://lookafteryoureyes.org/)

- ISO 24495-1:2023 [Internet]. ISO. 2023 [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.iso.org/standard/78907.html

- Fitzpatrick PJ. Improving health literacy using the power of digital communications to achieve better health outcomes for patients and practitioners. Front Digit Health. 2023 Nov 17;5:1264780.

- Hemingway Editor [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://hemingwayapp.com/

- Get your document’s readability and level statistics [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 26]. Available from: https://support.microsoft.com/en-gb/office/get-your-document-s-readability-and-level-statistics-85b4969e-e80a-4777-8dd3-f7fc3c8b3fd2

- Lim ZW, Pushpanathan K, Yew SME, Lai Y, Sun C-H, Lam JSH, et al. Benchmarking large language models’ performances for myopia care: a comparative analysis of ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4.0, and Google Bard. EBioMedicine. 2023 Sep;95(104770):104770.

- Gerken T. YouTube starts verifying health workers in the UK. BBC [Internet]. 2023 Sep 8 [cited 2024 Nov 19]; Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-66716501

- Ming S, Han J, Yao X, Guo X, Guo Q, Lei B. Myopia information on TikTok: analysis factors that impact video quality and audience engagement. BMC Public Health. 2024 Apr 29;24(1):1194.

- Zhang S, Zhou H, Zhu Y. Have we found a solution for health misinformation? A ten-year systematic review of health misinformation literature 2013-2022. Int J Med Inform. 2024 Aug;188(105478):105478.

- Li Q, Guo L, Zhang J, Zhao F, Hu Y, Guo Y, et al. Effect of school-based family health education via social media on children’s myopia and parents’ awareness: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021 Nov 1;139(11):1165–72.

- Nischal KK. Government instituted public health policy for myopia control in schools-the overlooked variable in myopia prevention interventions? EYE [Internet]. 2024 Oct 21; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41433-024-03406-5