[CaptionComponent="2917"]

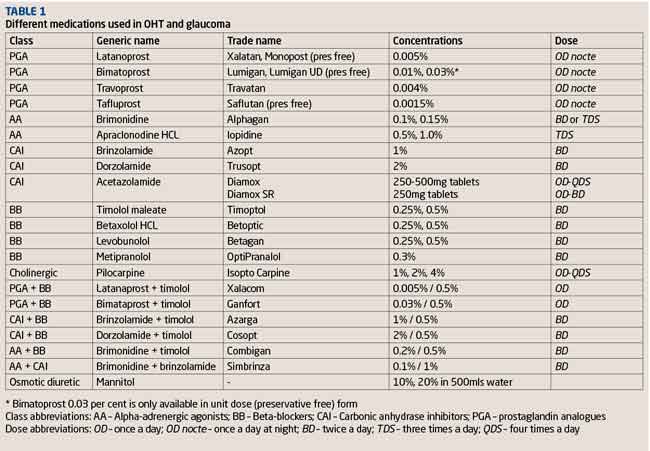

The medical management of glaucoma can seem like a minefield to some. Where do you start, and with what drops? What do you change to if the current drops need to be modified? There is a multitude of options available to choose from, and with drops being referred to either by their trade name or their generic name, this may add to the confusion. (Table 1)

The aim of this article is to cover the basic steps in medically managing ocular hypertension (OHT) and glaucoma.

When to start drops?

It is important to know when it is appropriate to recommend commencing a patient on treatment, or when it may be appropriate to observe them without treatment. Both the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the European Glaucoma Society (EGS) have published guidelines on the diagnosis and management of OHT and chronic open-angle glaucoma (COAG) in adults. In comprehensive reviews of the current literature they have both produced guidelines that advise when to start treatment and what to start with. We have focused on the NICE guidelines in this article.

What is the ‘ideal’ treatment?

If someone requires intraocular pressure (IOP) reduction then it must be borne in mind what would be the ‘ideal’ treatment for the patient to ensure optimal compliance and efficacy with no to minimal side effects (Table 2). Until newer therapies with a longer duration of action become available, for most people this would currently be a single once daily drop of one medication (monotherapy) which achieves a significant reduction in IOP without side effects.1

However, drops can cause significant side effects in some patients and minimal to no side effects in others. Furthermore, some will find drops easier to instil than others. It can therefore be challenging to reach a treatment that both suits a patient best and achieves target IOP.

Main drug categories

There are five main categories of drops and tablets used in the treatment of glaucoma.

Prostaglandin analogues (PGAs)

PGAs were introduced in 1996 and have revolutionised the treatment of OHT and glaucoma. They replaced beta-blockers as the first line choice of drops after proving to significantly lower IOP (latanoprost compared to timolol).2 PGAs are given once a day at night, controlling IOP through its diurnal and circadian fluctuations and are not as affected by tachyphylaxis (loss of effectiveness with repeated use) compared to other glaucoma drops.3 There are a variety of different forms of PGAs, with latanaprost the most commonly prescribed variant. It has recently come off patent from Xalatan (Pfizer) and at the last count there are currently 18 different versions of generic latanoprost. Generic versions of latanoprost are less expensive compared to Xalatan, which has beneficial cost implications to the NHS; however, patients who were previously used to using the Xalatan bottle for years may now be given a different bottle each month on their repeat prescription, depending upon which is dispensed by their pharmacist.

It has also been reported that some patients have not tolerated generic versions of latanoprost and that in others there has been less effective IOP lowering. Branded PGA variants include Travoprost (Alcon), and Bimatoprost (Allergan). There are now preservative free versions of PGAs; Monoprost (latanoprost, Spectrum Thea), Lumigan Unit Dose (bimatoprost) and Saflutan (tafluprost, Santen) which are more commonly used in patients who appear to be intolerant and experience significant side effects from the preservative benzalkonium chloride.

Beta-blockers (BBs)

Beta-blockers have been used to treat glaucoma since the 1970s and prior to the introduction of PGAs were the primary treatment for glaucoma.1 Today they are mainly a second-line therapy, often now used in combination drop form with other agents. They are available in non-selective and ß1-selective forms. They can be applied twice daily, but can also be dosed once daily to still achieve reduction of IOP over 24 hours.4,5 Circadian studies have shown Timolol to be less effective lowering IOP overnight compared to its effects during the day. 6

There are several co-existing medical conditions important to check for before prescribing a beta-blocker. These include asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure, bradycardia and heart block. Beta-blockers can potentially exacerbate these conditions and it is therefore not advisable to use them unselectively in such patients.

Alpha-adrenergic agonists (AAs)

There are two main variants of alpha-adrenergic agonists used today, apraclonidine (Iopidine) and brimonidine (Alphagan). In the UK, apraclonidine’s main use in glaucoma clinical practice is to prevent a post-laser (Nd:YAG peripheral iridotomy, YAG capsulotomy, selective laser trabeculoplasty or Argon iridoplasty) IOP spike, or as an adjunct in the management of acute angle closure glaucoma. It comes in two concentrations (0.5 per cent and 1 per cent) and the usual dose is twice or three times daily. The main limiting factor with apraclonidine is allergic blepharoconjunctivitis reported in as high as 48 per cent of patients with long-term use.7 Pupillary mydriasis and eyelid retraction are other unwanted side effects from the alpha-1 adrenergic receptor pathway.1,8

Brimonidine differs to apraclonidine in that it is a highly selective alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist. This means it avoids potential alpha-1 pathway related side effects. However, allergic blepharoconjunctivitis is still a notable side effect occurring in upwards of 15 per cent of patients.9

Brimonidine is usually used as a second or third line agent in the treatment of COAG, and is also used combined with a beta-blocker (Combigan, Allergan) or a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (Simbrinza Alcon).

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs)

CAIs are available in a systemic form as an oral tablet or intravenous injection (acetazolamide) or more commonly topically (dorzolamide, brinzolamide). The systemic form of acetazolamide is most commonly used in the management of acute angle-closure glaucoma or in circumstances of very high IOP, but its use in treating chronic glaucoma is limited by systemic side effects (Table 2). Topical CAIs have significantly fewer side effects than systemic treatment and are used as second- or third-line therapy in the treatment of COAG, often in combination with timolol.

Cholinergics

Pilocarpine is the only cholinergic used in the UK. Its main roles are in angle-closure glaucoma, intermittent angle-closure and pre-Nd:YAG peripheral iridotomy. It is now rarely used in the long-term management of glaucoma due to side effects including reduced vision from miosis, induced myopia, and brow ache.

OHT or suspected COAG

OHT can be defined as untreated IOP of greater than 21mmHg, confirmed on at least two separate occasions in a patient with open angles, with the absence of optic disc damage, nerve fibre layer (NFL) loss or visual field (VF) loss.10 NICE glaucoma guidelines recommends the treatment of OHT based on a patient’s age, their central corneal thickness (CCT) and untreated IOP measurement (Table 3).10 For example if the cornea is greater than 590 microns thick, and the IOP is between 21-32mmHg then no treatment is recommended. If the cornea is between 555-590 microns thick and the IOP is between 25-32mmHg then a patient should be treated with a beta-blocker until they are 60 years old. At this point, after discussion with, and with the agreement of the patient, treatment could potentially be stopped if there is no evidence of glaucoma. If the cornea is thin, less than 555 microns then a PGA is recommended.10

Once someone has been started on treatment for OHT or as a glaucoma suspect, then they need to be monitored. Monitoring involves assessing if their IOP is now at target and assessing the patient’s risk for converting to glaucoma (Table 4). If their IOP is at target and they are deemed low risk to convert to glaucoma, then they can be followed up in 12-24 months for reassessment to include optic nerve head and visual field examination. If their IOP is at target but they are deemed high risk for conversion, then the follow-up period should be 6-12 months.

Patients whose IOP is not at target but are low risk for conversion should have their treatment adjusted, an IOP check in 1-4 months and a full reassessment at 6-12 months. Those who have high IOP and are high risk for developing glaucoma should have their treatment readjusted an IOP check in 1-4 months and a glaucoma reassessment in 4-6 months.10

Chronic open-angle glaucoma (COAG)

COAG is the term used when a patient has open angles, with a visual field defect associated with glaucoma, optic disc cupping, neuro-retinal rim loss or nerve fibre layer loss.10 There are different types of COAG; primary open angle glaucoma (when treated or untreated IOP is raised above 21mmHg), normal tension glaucoma (untreated IOP is <21mmHg), or glaucoma secondary to pseudoexfoliation syndrome and pigment dispersion syndrome.10

Once a patient has been diagnosed and initiated on treatment for COAG they have to be followed up to ensure the glaucoma is not progressing. NICE have suggested a management and follow-up algorithm as outlined in Table 5.

When to switch or add drops

Switching or adding topical therapy is generally related to three reasons: inadequate IOP control, progression of the disease or medication side effects. Altering therapy may involve switching to a different drop in the same class, a preservative free version, or switching or combining with a different drop from another class. It is good practice to document clearly what reaction the patient had to the drop for future information, as similar situations may arise with other drops.

Clinicians will have their own personal preferred drop escalation regimen which comes from their personal experience with managing patients with glaucoma. Other adjuncts such as selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) or surgery could also be considered.

Alternative and non–traditional treatments for glaucoma

The medical philosophy is often to treat only with evidence-based medications. There is anecdotal evidence supporting other potential natural compounds that have not yet been robustly researched in high quality clinical trials which may be beneficial in the prevention and treatment of glaucoma. These include omega-3 fatty acids and extracts from the Ginkgo biloba tree among others.11,12

Compliance and adherence

Adherence to treatment of chronic disease is estimated at 75 per cent but may well be lower with diseases such as glaucoma whereby most patients are asymptomatic in the early stages.13 Many patients will have different understanding and perceptions of their disease. Some will religiously adhere to their treatment regimen; others however, may not, particularly as they are often visually asymptomatic. It is therefore an important part of the consultation to determine a patient’s understanding of their disease, and the importance of complying and adhering with treatment.

Complex dosing regimens may have a detrimental effect on compliance to medication. Therefore the patient’s treatment regimen should be simplified where possible. The introduction of combination drop therapy has helped this.

Compliance aids or applications can be very helpful to patients who may forget or struggle to instil eye drops. This is an often an important or forgotten adjunct.

Future therapies

Current medical treatments only lower IOP, a predominant risk factor for glaucoma. Unfortunately, medications are often not completely effective, and management is significantly reliant on patient compliance and technique. Some future therapies aim to reduce the reliance on the patient. Mechanisms include making slow release preparations of the drugs which can be implanted in the conjunctival fornix sub-conjunctivally, trans-sclerally, intra-vitreally or even placed as a punctual plug.3

Research is also currently looking at developing new classes of drugs which target different mechanisms to lower IOP. These include Rho-kinase inhibitors which lower IOP by targeting the cytoskeleton of the trabecular meshwork endothelial cells.3

Conclusion

NICE and the EGS have both developed clear guidelines with treatment algorithms based on the most up-to-date literature to assist clinicians to manage glaucoma. Medical management with drops is predominantly the first line of treatment, which can be escalated with a change of, or additional drops. If glaucoma continues to progress with medical therapy alone insufficient, laser and or surgical therapies are often then considered (see Part 4 of this series to be published next month).

Model answers

Which of the following is NOT a category of drug used in glaucoma treatment?

D Beta-adrenergic agonists

Which of the following is currently recognised as the first choice for pharmaceutical control of IOP?

D Prostaglandin analogues

To which of the following drug categories does apraclonidine belong?

B Alpha-adrenergic agonists

Which of the following statements about systemically-administered is acetazolamide false?

C It is preferred to topical application in glaucoma management

Which of the following may cause a dry mouth?

B Alpha-adrenergic agonists

According to the NICE guidelines, what is the recommended IOP monitoring interval for a patient with target IOP but is exhibiting some disease progression?

B 1 to 4 months

References

1 Whitson JT, Aggarwal NK. Ophthalmology research: Mechanisms of the Glaucomas. Edited by J Tombran-Tink, CJ Barnstable and MB Shields. Towota, New Jersey: Humana Press.

2 Camras CB. ‘Comparison of latanoprost and timolol in patients with ocular hypertension and glaucoma: a six-month masked, multicenter trial in the United States. The United States Latanoprost Study Group.’ Ophthalmology, 1996; 103: 138–147.

3 Schacknow PN, Samples JR. The Glaucoma Book: A Practical, Evidence-Based Approach to Patient Care. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 2010.

4 Zimmerman TJ, Kaufman HE. ‘Timolol, dose response and duration of action.’ Arch Ophthalmol, 1977; 95: 605–607.

5 Soll DB. ‘Evaluation of timolol in chronic open-angle glaucoma: once a day vs twice a day.’ Arch Ophthalmol, 1980; 98: 2178–2181.

6 Liu JH, Kripke DF, Weinreb RN. ‘Comparison of the nocturnal effects of once-daily timolol and latanoprost on intraocular pressure.’ Am J Ophthalmol, 2004; 138: 389–395.

7 Butler P, Mannschreck M, Lin S, et al. ‘Clinical experience with the long-term use of 1 per cent apraclonidine.’ Arch Ophthalmol, 1995; 113: 293–296.

8 Wilkerson M, Lewis RA, Shields MB,. ‘Follicular conjunctivitis associated with apraclonidine.’ Am J Ophthalmol, 1991; 111: 105–106.

9 Schuman JS, Horwitz B, Choplin NT, et al. ‘A 1-year study of brimonidine twice daily in glaucoma and ocular hypertension: a controlled, randomized, multicenter clinical trial (Chronic Brimonidine Study Group).’ Arch Ophthalmol, 1997; 115: 847–852.

10 Sparrow J et al. Glaucoma: Diagnosis and management of chronic open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009.

11 Nguyen CTO, Bui BV, Sinclair AJ, et al. ‘Dietary omega 3 fatty acids decrease intraocular pressure with age by increasing aqueous outflow facility.’ Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci, 2007; 48: 756-762.

12 Mancino M, Ohia E, Kulkarni P. ‘A comparative study between cod liver oil and liquid lard intake on IOP in rabbits.’ Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids, 1992; 45: 239-243.

13 DiMatteo MR. ‘Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research.’ Med Care, 2004; 42: 200-209.

Dr Nicholas Hickley is a specialist trainee in ophthalmology. Mr Dan Nguyen is a consultant ophthalmologist and the lead clinician for glaucoma at Mid-Cheshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. He is a consultant ophthalmologist at Optegra Manchester Eye Hospital where he also collaborates with Optegra’s Eye Sciences associates