Trachoma is the leading cause of preventable blindness worldwide. The disease induces blindness through repeated infection of the causative organism Chlamydia trachomatis, writes Dr Iain Phillips

Trachoma is the leading cause of preventable blindness worldwide. The disease induces blindness through repeated infection of the causative organism Chlamydia trachomatis, writes Dr Iain Phillips

Chlamydia trachomatis

There are three main bacterial pathogens in the genus chlamydia. These are Chlamydia trachomatis, C psittaci and C pneumoniae. C psittaci causes psittacosis and C pneumoniae is known to cause respiratory tract infections including pneumonia.

There are 15 serotypes of C trachomatis and the pathology caused by the infection relates to the serotype. Trachoma is caused by serotypes A, B, Ba and C. The sexually transmitted disease caused by C trachomatis is caused by serotypes B, Ba and D to K. As well as causing infections such as urethritis and cervicitis, infection can lead to inclusion body conjunctivitis in both adults and neonates. Lymphogranuloma venereum is caused by serotype L. This is a disease of the genitalia, starting with the formation of a localised genital ulcer and inducing regional lymphadenopathy.

Chlamydia bacteria are obligate intracellular parasites. These bacteria can only grow and replicate inside a cell.1 They lack the necessary metabolic pathways (particularly ATP metabolism) to maintain extra cellular multiplication. This means that they require the host cell to provide compounds such as ATP and particular amino acids. The bacteria survive in intra cellular vacuoles called inclusion bodies. When first discovered the lack of extra cellular activity led researchers to believe they were viral organisms. The presence of bacterial machinery, however, including ribosomes, a cell wall, and both DNA and RNA, indicates they are bacteria.

Chlamydia life cycle

The chlamydia life cycle is unique in the use of two distinct morphological forms to overcome the lack of extra cellular activity. The extra cellular form is the elementary body and the intra cellular form is the reticulate body. The life cycle is divided into five distinct steps. The first step is the attachment of the elementary body to the potentially infected cell through a ligand-receptor interaction. Once bound the bacterium penetrates the cell. Gaining entry to the cell is achieved by the bacterium altering the membrane and cytoskeleton structure in 'non-professional' phagocytes,2 through a mixture of endocytosis, phagocytosis and pincytosis.

Once inside the infected cell, the elementary body undergoes a morphological change to become a reticulate body. The reticulate bodies use the readily available intra cellular metabolites (such as ATP), to undergo cellular growth and replication.

The fourth stage of the life cycle is a reversal of these new reticulate bodies into hardy elementary bodies. The final stage is the release of these infectious particles from the infected cells.3

The host cells use several mechanisms to prevent infection. These include phagocytosis and lysosyme. Phagocytosis is a process used by particular white blood cells in the body to engulf pathogens. This particular population of cells' (including macrophages and dendritic cells) main function is phagocytosis of pathogens. These 'professional phagocytes' then process the pathogen and initiate immune system activation. The host cell binds a membrane bound 'soup' of destructive enzymes (called a lysosome) to the phagocytosed material. This kills the pathogen.

The chlamydia bacteria reduce the efficacy of the host defences in several ways. They avoid typical phagocytosis by inducing the process in non professional phagocytes. They are also able to prevent lysosyme fusion to the internalised material. Chlamydia infection occurs in epithelial cells, where fewer professional phagocytes are found.

PATHOLOGY OF C TRACHOMATIS

Inclusion body conjunctivitis

C trachomatis can cause two types of infective eye disease. The first is trachoma, the second is called inclusion body conjunctivitis and is related to genital chlamydia infection, which can occur in neonates or adults. If the mother has a genital chlamydia infection, then the neonate can be infected during passage through the birth canal. This is known as neonatal inclusion conjunctivitis. Approximately a third of neonates born to women with chlamydia develop conjunctivits. It usually presents 5-12 days after birth, but can present up to six weeks after birth. A similar infection can also be seen in adults.

Half of those adults who develop inclusion conjunctivitis have documented concurrent genital chlamydia. In these cases the source of infection is likely to be autoinoculation.4

Contact tracing of sexual partners should be carried out to ensure the infection is not spread. The cause in those without urogential disease is less clear. Urogenital chlamydia infection is thought to be silent, without symptoms in 50 per cent of women.

Chlamydia is an increasingly important cause of infertility. As the infection can be silent, it can lie undiagnosed for many years. Chronic infection leads to infertility through chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, fallopian tube infertility and spontaneous abortion. Other important sequaelae include ectopic pregnancy and chronic pelvic pain syndrome.

Trachoma

Trachoma is the leading cause of infectious blindness world wide. The disease is more commonly found in dry, arid areas. It is found in many areas around the world, including Africa, the Middle East, south east Asia and the Indian sub continent. It can also be found in Australia, Central and South America and parts of the Pacific. Of the 500 million people affected, some nine million are blind. The number of people affected in endemic areas is staggering. Everyone over the age of one will have clinical signs of trachoma infection. A quarter of those over 60 will be blind, due to the nature of the pathology, chronic repetitive infection.

The most important risk factor leading to loss of vision associated with trachoma is the level of repetitive infection of an individual. The first or a single episode of chlamydia conjunctivitis causes a self-limiting infection. However, reinfection leads to the severe inflammation associated with chronic trachoma.

Other risk factors include facial cleanliness, distance from nearest water supply, the density of household flies, larger families (with less attention regarding cleanliness of the individual) and certain religious beliefs are all associated with increased risk of trachoma. A positive history of these risk factors makes the cycle of repeated infection in an individual more likely.

Infection leads to severe inflammation and can be spread in several ways. The disease can be spread within the same individual from infected tissue to uninfected tissue. Elementary bodies can be spread from genitalia to eye or vice versa. The disease can be spread through sexual intercourse if urethritis or cervicitis is present.

If chlamydia is present in the genital tract, it is possible to transmit the pathogen to a newborn baby. This leads to inclusion body conjunctivitis. The disease can be spread through fomites as the elementary bodies are able to survive in a similar way to fungal or bacterial spores. A fomite is an inanimate object used to transfer an infection. In this context they may include towels, clothes and flies. Flies feed on the exudate in the secretions of the infection. The largest reservoir of infection resides in young children. This explains why women (who are caring for the children) have a four-fold increased risk of developing trachoma.

If chlamydia is present in the genital tract, it is possible to transmit the pathogen to a newborn baby. This leads to inclusion body conjunctivitis. The disease can be spread through fomites as the elementary bodies are able to survive in a similar way to fungal or bacterial spores. A fomite is an inanimate object used to transfer an infection. In this context they may include towels, clothes and flies. Flies feed on the exudate in the secretions of the infection. The largest reservoir of infection resides in young children. This explains why women (who are caring for the children) have a four-fold increased risk of developing trachoma.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Neonatal inclusion conjunctivitis

Infection is typified by a watery discharge from the eye, which progressively becomes more purulent. The eyelids swell and the conjunctiva becomes red, inflamed and thickened. If left untreated the disease lasts from three to 12 months. However, a mild sub-clinical form of the disease can persist for several years. This can lead to scarring and corneal lesions. This type of conjunctivitis is associated with rhinitis and genital inflammation in female infants.

Adult inclusion conjunctivitis

Chlamydia infection of the eye occurs in the form of an acute follicular infection. In early infection (first two weeks) there is hyperaemia and a mucoid discharge, which becomes increasingly purulent. Lymphoid follicle formation occurs and can often progress to epithelial keratitis and the development of corneal lesions. Blood vessels invade the cornea, causing pannus formation.

It is not possible to differentiate this condition from early trachoma infection. Otitis media and pre-auricular lymphadenopathy are other clinical signs that may be associated with the infection.

Inclusion conjunctivitis rarely becomes a chronic infection displaying signs of trachoma. However, in most cases it is a self-limiting disease that does not lead to a loss of vision. A differential diagnosis must include viral conjunctivitis. It is difficult to gain a definitive diagnosis without demonstrating the presence of the organism, either through culture of the bacteria or polymerase chain reaction of viral material.

Trachoma

The severe inflammation and cycle of reinfection means that the clinical appearance of the eye can be used to identify the severity of the disease.

The first trachoma infection is very likely to occur before the age of two. This active disease can then persist for several years. To assist in diagnosing and grading the severity of the disease the World Health Organisation (WHO) has designed a simple grading system.

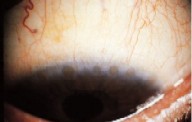

Initial trachoma infection shows active inflammation and is characterised by the presence of follicles in the superior tarsal conjunctiva. Follicles are elevated (0.25-2mm) pale yellow or white spots. They are germinal centres composed of immune cells, B lymphocytes surrounding a core of T lymphocytes. The conjunctiva becomes thickened and papilla (red dots) are seen. Papilla are associated with trachoma infection, but are not specific. Their number dramatically increases in the presence of a secondary bacterial infection. If follicles are present, then the number of the papilla is proportional to the severity of the trachoma infection. If there is severe inflammation of the tarsal conjunctiva it becomes velvety red in colour.

During active infection other features can include a punctate keratitis and the presence of inflammatory infiltrates in the superior cornea. As the chronic infection develops, corneal opacification begins to develop. New blood vessel formation leads to pannus formation, which is characteristic of trachoma infection. Pannus can extend onto the cornea. However, it is rare for it to spread sufficiently to affect vision. The follicles seen in acute infection resolve leaving depressions in the conjunctiva. These lesions are clear and known as Herbert pits.6

The disease does not produce many symptoms in the early stage, unless there is a secondary bacterial infection. The major feature of chronic trachoma is repeated infection and as a result inflammation that leads to scarring. The scarring process begins with small stellate areas which coalesce and accumulate to form a basket weave network. These patches of scar tissue combine to form thick bands of scar tissue across the conjunctiva. This process of fibrosis is achieved through the collection of extra-cellular matrix. This process is mediated by the expression of fibrogenic growth factors.7

A distinctive band of scar tissue called Arlt's line can develop. This is a line of scar tissue that develops in parallel and above the lid margin. As the follicles and patches of scar tissue coalesce, it is difficult to tell between the two. The scarring disrupts the normal anatomy of the eye in two ways. Firstly, the process of scarring the conjunctival tissue distorts and buckles the tarsal plate. An early sign of this can be seen in the loss of regular alignment of the meibomian glands. Secondly, the tissue contracts pulling the margin of the eyelid inwards, causing entropion.

The consequence of the eyelid turning in, is the eyelashes continually rub against the surface of the cornea. This causes damage to the cornea. Over time it causes corneal oedema, ulceration and ultimately opacification and blindness.

Laboratory Diagnosis

The traditional method of diagnosis was to stain conjunctival scrapings of a suspected infected individual with Giemsa stain. This technique has been superseded by more accurate, sensitive and specific diagnostic tests. Techniques such polymerase chain reaction are thought to be highly sensitive to clinical infection. Of those with clinical signs of disease, only two thirds with severely inflamed eyes and a quarter of those with active disease have laboratory signs of infection. Laboratory diagnosis is often unavailable in areas of endemic trachoma, as a result the disease is often diagnosed clinically using the WHO grading scheme.8

Trachoma treatment

Trachoma is a major public health problem and, as a result, strategies need to be implemented to prevent the spread of the disease as well as treating the infected individuals. The WHO has launched a programme to eliminate trachoma by 2020,9 through the use of the SAFE campaign. This stands for Surgery for Trichiasis, Antibiotic provision, Facial cleanliness and Environmental improvement.

Environmental factors are important in reducing the incidence of the disease, as well as stopping the disease causing reinfection after eradication using antibiotics. Simple measures can drastically reduce the incidence of trachoma. These include reducing the density of the fly population and regular face washing. It has been shown that using insecticide to control the fly population reduces trachoma by 55-61 per cent.10

The choice of antibiotic therapy has been the cause of some debate. A range of antibiotics have been used including tetracycline, erythromycin and sulphonamides. The traditional mainstay of treatment has been topical tetracycline. It has made little impact on a community-wide level and side effects mean it should not be used as a systemic antibiotic in children.

Systemic antibiotic use appears to reduce the complications of the disease, as well as reducing the rate of secondary bacterial infection. If the antibiotics are not given systemically and not given to all of the community, the disease will continue to be transmitted. This occurs for several reasons, firstly topical antibiotics only temporarily reduce the presence of chlamydia bacteria in the eye. Secondly if antibiotics are not given community-wide the infection will pass from those who still have the disease to those who do not.

Recent research suggests that single dose antibiotics in low prevalence areas give effective C trachomatis control.11 The most effective antibiotic appears to be azithromycin. This is an erythromycin derivative and is effective as a single dose due to its sustained concentration in the body (20mg/kg).12 It also has the advantage that it is less expensive than tetracycline or erythromycin. In hyperendemic areas bi-annual treatment with azithromycin prevents trachoma recurrence.13

Surgical options in treating trichiasis are important to prevent blindness. The aim of surgery is to correct chronic corneal damage caused by the continual rubbing of eyelashes. Surgery is indicated when one or more eyelashes turn in and touch the cornea, with the patient looking straight ahead. Although many different procedures have been tried, it appears that a simple process of tarsal rotation is effective.

SAFE combines simple prevention such as facial cleanliness with new drugs and surgery. It is hoped that the future of trachoma and its treatment is the elimination of the disease. The use of the SAFE campaign suggests that we now have the weapons to defeat trachoma.14 It is likely that mathematical modelling will be necessary to predict the best strategy to eradicate the disease.

Research has shown that raising economic standards leads to a decrease in the disease. Many questions, however, remain unanswered. These include the reasons for recurrence of infection after antibiotic use and how these infections can be minimised, more research is necessary to understand a disease that has been known for at least 3,500 years. Unlike many other causes of visual loss, trachoma is a preventable disease and we have the means to eradicate it.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks David and Sharon Phillips for their help with this article.

REFERENCES

1 Jutras I, Abrami L et al. Entry of the lymphogranuloma venereum strain of Chlamydia trachomatis into host cells involves cholesterol-rich membrane domains. Infection and Immunology, 2003;71(1):260-6.

2 Balana M, Niedergang et al. ARF6 GTPase controls bacterial invasion by actin remodelling, Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118(10):2201-2210.

3 Schachter J. Chlamydia. In: Infectious Diseases. Eds Gorbach S, Blacklow N et al. W B Saunders Company. 1992:244;1633-1640.

4 Thylefors B, Dawson C et al. A simple system of the assessment of Trachoma and its complications. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 1987;65:477-483.

5 Taylor H and Vajpayee R. Tropical Ophthalmology. In: Oxford Textbook of Ophthalmology, 1st edition. Eds Easty D and Sparrow J. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999:361-365.

6 Weir E. Trachoma:leading cause of infectious blindness, Canadian Medical Assocation Journal, 2004;170(8):1225.

7 Stamm E, Jones R et al. Chlamydia trachomatis. In: Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 6th edition. Eds Mandell G, Bennett J et al, 2005: 2239-2251

8 Melese M, Alemayehu W et al. What more is there to learn about trachoma? British Journal of Ophthalmology, 2003;87:521-522.

9 Rabiu M, Alhassan M et al. Environmental sanitary interventions for preventing trachoma. Cochrane database system review, 2005;April 18 (2)CD004003.

10 Burton M, Holland M et al. Re-emergence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection after mass antibiotic treatment of a trachoma endemic Gambian community: a longitudinal study. Lancet, 2005;365(9467):1321-8.

11 Abu El-Asrar A, Al-Kharashi S et al. Expression of growth factors in the conjunctiva from patients with active trachoma. Eye, 2005. Published online

12 Solomon A, Holland M et al. Mass Treatment with single dose azithromycin for trachoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 2005;352(4):414-415.

13 Melese M, Chidambaram J et al. Feasibility of eliminating ocular Chlamydia trachomatis with repeat mass antibiotic treatment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2004;292(6):721-725.

14 Frick K, Hanson C et al. Global Trachoma and economics of disease. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2003;69(supplement 5):1-10.

- Dr Iain Phillips is a house officer with a special interest in infectious diseases