This article aims to summarise the key points made in the preceding three articles in the series and explain how best to apply this knowledge in everyday eye care practice. But, to begin with, a note about appropriate terminology.

‘Autistic person’ or ‘person with autism’?

To the non-autistic person, describing someone as being autistic or having autism probably does not appear any different. In fact, they are likely to gravitate towards the latter person-first language, which is the preferred terminology by healthcare providers. Person-first language puts the person before the diagnosis (e.g., person with diabetes) and advocates valuing the individual, not allowing the health condition to define them. This seems appropriate for ensuring the person is ‘seen’ before the condition they have, and for motivating an individual to not allow their health problems to limit them.

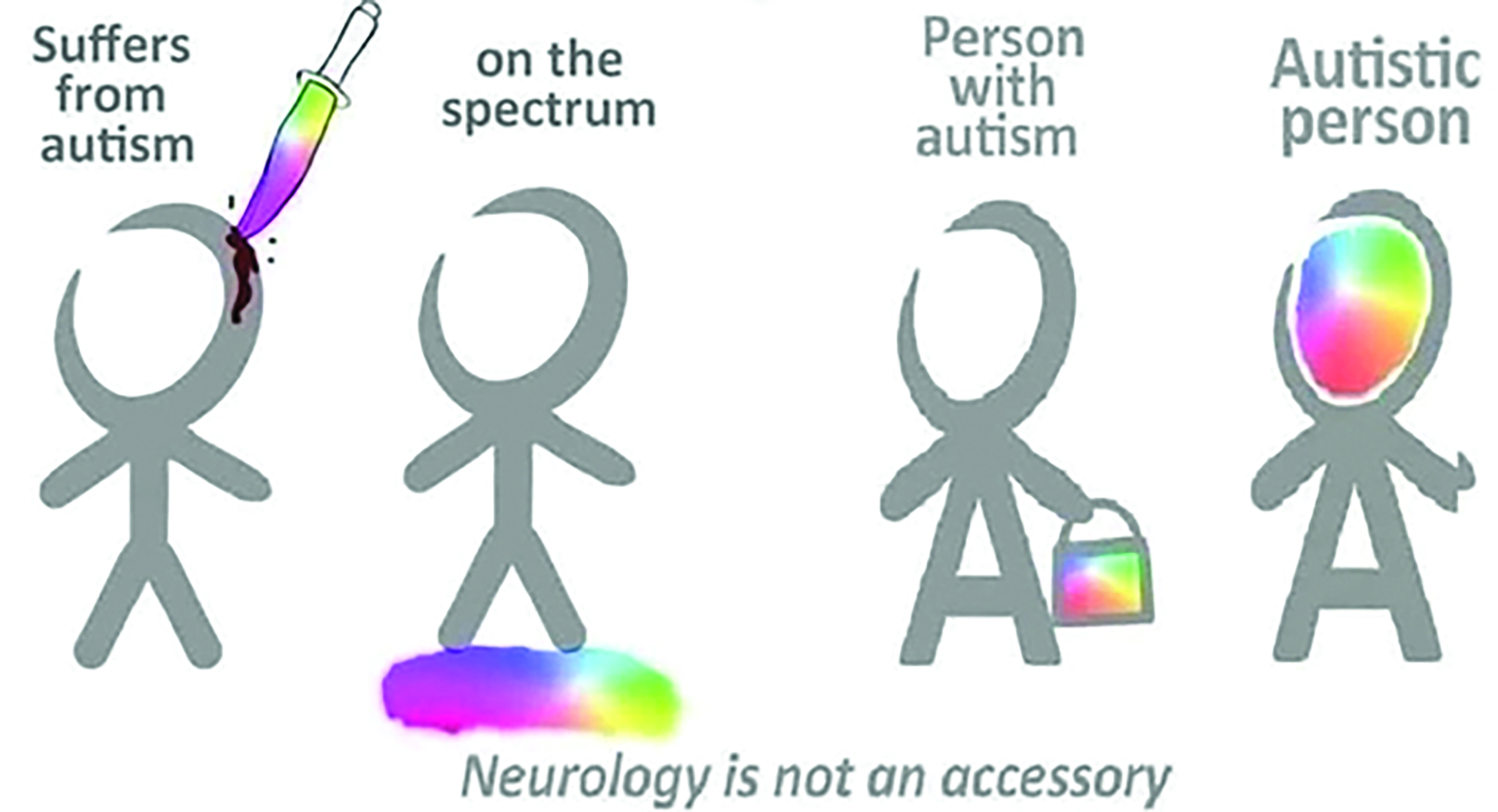

Autism affects the day-to-day living, decisions and experiences of autistic people. But, autism cannot be compared to health conditions such as diabetes or heart disease, which can be developed, controlled or resolved. Although there is debate, the majority of autistic adults, family members and friends strongly prefer identity-first language;1 that is using the prefix ‘autistic-’. Saying ‘person with autism’ implies that autism is a negative add-on. Many autistic people seek and see the strengths of this lifelong neurodevelopmental condition. Autistic people would rather embrace their autism and its features (figure 1).

Figure 1: An image portraying the implications of different terminology used to describe autism. The majority of autistic people prefer identity-first language. [Figure courtesy of identityfirstautistic.org]

A common analogy, which exemplifies the importance of this variation in language, is saying ‘person with femaleness’ (person-first language) instead of ‘female’ (identity-first language). Identity-first language for autism also aligns with recommendations from NICE,2 the National Autistic Society3 and Autistica.4 Therefore, healthcare professionals should use the term ‘autistic person/individual/adult/child’.

What we have learned

Autism affects social interaction, communication and behaviour. The condition has a global prevalence of 0.6%.5 Approximately 1.1% of adults6 and 1.57% of children7 are diagnosed as autistic in the UK, although these are likely to be underestimates due to under-diagnosis in females,8 adults9 and ethnic minority groups.10 Up to four times more males are diagnosed as autistic than females,11, 12 and around one-third of autistic people also have a learning disability.13

The majority of autistic people experience altered sensory reactivity,14, 15 meaning they can have increased or reduced sensitivity to sensory stimuli. Additionally, autistic people can display sensory seeking behaviours, such as excessive touching of object edges or fascination with reflections.16 Altered sensory reactivity mostly takes the form of hypersensitivity for autistic individuals,17 but importantly sensory issues are lifelong,18 affect each sense19, 20 as well as multisensory processing.21, 22 The experience can be stressful or pleasant, depending on the nature of the stimuli.23, 24

Part 1 of this series (see Optician 29.07.22) discussed an understanding of autistic sensory issues, focusing on vision. Autistic adults can experience a variety of visual symptoms (the majority being sensory), for example, to different aspects of light (bright, strip and focused lighting), colours, patterns, motion and visual clutter. These can occur alone or contribute to larger multisensory experiences. Although non-autistic people would probably experience some of these symptoms, it is the challenge in daily activities, such as the ability to visit public places or use public transport, which seems to be greater for autistic people. Visual sensory issues also negatively impact physical, emotional and mental wellbeing. Autistic people try to control the effects of visual experiences but with limited success. Coping strategies can involve adapted lighting, avoiding situations that provoke visual sensory experiences, specific eyewear and just trying to cope as best possible.

Where coping is difficult, some autistic people have accessed unregulated management options, such as tinted lenses, which claim to have a calming effect in this population (www.read123.co.uk/en/the-use-of-colour-therapy-and-coloured-lenses-in-autism).

Although visual acuity is comparable between autistic and non-autistic people,25 autistic people may be at greater risk of developing optometric anomalies including higher or significant changes in refractive error, visual stress and binocular vision anomalies: convergence insufficiency, strabismus, amblyopia and accommodative issues.26-28 Overall, if autistic people are more likely to develop optometric issues, they can be expected to need to visit an optometrist regularly.

Part 2 of this series (see Optician 26.08.22) explored the key challenges that autistic adults face when attending eye examinations.29 These begin from the point of booking the examination, to arriving at the practice, and undergoing multiple tests with different staff members. Autistic people can feel anxious and therefore avoid interacting with ‘strangers’, especially over the phone. Sensory issues caused by lights, colours, noise and lots of people can affect how an autistic person feels in the practice. The patient journey, adopted by many optometric practices, can be difficult for autistic adults because it takes them time to feel comfortable around different members of staff. Autistic people feel more confident with an optometrist that they see regularly, regardless of the practitioner’s competence.

In the testing room itself, poor communication from the optometrist can leave autistic people worried about their responses to subjective tests and subsequently the outcomes of the examination. However, the uniform structure, together with the variety of tests and gadgets used during an eye examination creates an interesting experience for some autistic adults. As a result of the significant challenges surrounding eye care, autistic adults can avoid eye examinations. It is evident that when considering how to improve eye care accessibility for autistic people, providers need to take a holistic approach. Failing to ask about accessibility needs, which is a legal requirement as per the Accessible Information Standard,30 does not help service providers in considering and preparing for eye examinations with autistic people.

Eye test-specific feedback was sought from autistic adults,29 presented in part 3 of this series (see Optician 23.09.22). The eye examination comprises multiple tests, which assess ocular functions, neurological aspects and eye health. However, having to undergo so many tests can leave autistic people feeling distressed.29 Tests involve strong sensory stimuli (e.g., bright lights, and contact from instruments), close proximity and decision-making. These factors can cause stress and anxiety for autistic adults. Although it may not be possible to eliminate these challenges, optometrists can consider how they could be reduced. Autistic people like being told what the tests are for, what equipment will be used, why the test is important and what they will have to do. They appreciate the opportunity to ask questions and being told test outcomes. The practitioner being aware of patient comfort, by having a friendly tone, speaking at a good pace and offering optional breaks, is reassuring.

To further enhance an eye examination experience, practitioners can use aids to help patients describe test results. Furthermore, they can consider conducting more challenging tests earlier in the routine, having some soft background music and allowing patients to handle their own eyelids when instilling drops.

Based on eye examination experiences of, and interview feedback from autistic adults, Parmar et al29 developed recommendations for eye care providers on how they can deliver more autism-friendly services. The majority of these are easy-to-implement, and are discussed in the following section.

Recommendations for providing autism-friendly services

Is your practice ready for autistic patients?

Here are some key steps to consider.

1. Improve your understanding of autism

Staff should consider undertaking autism awareness training. Having a basic awareness of autism will allow you to appreciate the challenges that an autistic person could face in your practice. This will help you consider adaptations for an autism-friendly

service.

Autistic people can feel anxious about eye examinations. They can be made to feel relaxed by staff simply introducing themselves, being patient, explaining procedures well and not providing too much information at once. It is a good idea to have an ‘autism champion’ among your practice staff. This is someone who has an advanced understanding of autism. They can be a point of contact for autistic patients. Other practice staff can seek their advice on autism-friendly adaptations.

2. Autism-friendly practice operation

Entering an optometric practice can be stressful for autistic people, partly because of glaring reflections from displayed spectacle frames and uncomfortable lighting. Autistic people can be hypersensitive to lots of sound or movement, and can feel anxious among lots of people. Identify patterns of quieter periods in your practice and offer appointments during these times to autistic patients. You could have ‘quiet times’ akin to some supermarkets, when practice lights are dimmed and the practice music is turned off. Similarly, consider whether autistic patients could be offered a ‘quiet area’ in your practice to wait instead of a busy waiting area, or possibly have them taken into the testing room straight away.

Some autistic patients may become overwhelmed with the variety of stages, staff and tests involved in an eye examination. If this is evident then offer spreading the appointment over two visits.

3. Try to provide practitioner continuity

It takes time for autistic individuals to feel comfortable around new people. Not only is staff continuity important during an appointment, but also across appointments. Seeing the same optometrist and dispensing staff at subsequent visits allows autistic patients to come to a familiar face, someone who already understands them.

Key steps to consider when booking the appointment are as follows:

1. Provide an electronic booking option

Many autistic people do not like speaking to strangers over the phone. Booking important healthcare appointments can be challenging if telephone is the main method of contact. Therefore, your practice should provide an alternative such as an online booking portal or appointment request form (perhaps, as part of your practice website), or the option for patients to communicate with the practice by email.

2. Accessibility or special requirements

By law, you should ask patients about their accessibility needs. You could add a free-text field to your electronic booking form asking about special requirements. Additionally, you could give examples of adaptations you are able to offer, such as extended appointments and quiet periods. For autistic patients who are comfortable booking appointments via telephone, ensure you seek accessibility information as part of the conversation. Ensure you review this information prior to the appointment. Doing so will allow you to understand any factors that may influence the eye examination.

3. Provide ‘what to expect during your appointment’ information

To reduce autistic patients’ eye examination anxiety, help them prepare for their visit by sending information about what the appointment will involve, which staff they will meet and the different processes they will undergo. This can take the form of an information sheet with pictures accompanying room, staff and test descriptions. This weblink is a useful resource that you can provide to autistic patients: https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/autism-and-vision/patient_resources/

Tips to improve the autistic patient’s visit are as follows:

1. Prepare the autistic patient for what to expect during the appointment

When an autistic patient arrives, sit with them in a quiet space and run through what will be involved in the appointment. Mention having to go to different rooms and which staff they will meet. Of course, if they were sent ‘what to expect during your appointment’ information, then conversation will serve as a good recap.

2. Minimise the number of staff and rooms involved in the visit

Autistic people can feel uncomfortable around strangers. Therefore, having to interact with different staff during an eye examination can cause significant stress. Try to conduct most of the appointment between the optometrist and dispensing staff. The optometrist can conduct pre-screening tests as well as the eye examination. The dispensing staff can fully manage any spectacle dispensing.

Having to go to different rooms is also anxiety provoking for autistic patients, because they have to get used to a new environment. Review your eye examination process and consider how the number of room changes could be minimised during an appointment.

3. Establish a good rapport

The interpersonal relationship between autistic patients and practice staff has a significant impact on the eye examination. It is important that practice staff introduce themselves and describe what they will be doing. For example, ‘my name is Ketan and I will be helping you choose a new pair of spectacles.’ Staff should ensure a kind tone and friendly behaviour. They should be reassuring and avoid rushing the autistic patient. It is also important to be aware of the autistic patient becoming stressed or overwhelmed.

Tips for optometrists during the eye examination:

1. Give clear explanations for each test

Autistic people value understanding:

- a) What test is being conducted

- b) How it will be conducted

- c) Why it is important

- d) What equipment will be used (if any)

- e) What they exactly need to do

When giving test instructions to autistic patients, optometrists should not make any assumptions. For example, when conducting subjective refraction optometrists should describe exactly what the autistic patient should be judging and if they should expect to see no difference between lens options: ‘I am now going to show you two lenses. Tell me which of these make the circle appear clearest and roundest. If you can’t choose between the two that is fine, just let me know.’

Optometrists should report test outcomes to the autistic patient throughout the examination. This includes showing and describing retinal images. If this is not immediately possible then inform the patient.

2. Adapt your routine as per the autistic patient’s special requirements

Autistic people can be hypersensitive to lights and skin contact. Therefore, think about if tests involving these could be replaced or conducted without provoking sensory issues. Near point of convergence can be estimated with a fixation stick instead of using an RAF rule. If it is not possible to replace the test, try to minimise the patient’s exposure to the uncomfortable stimulus. For instance, rather than assessing pupil reactions and ocular health at separate points in the examination, combine them consecutively.

Subjective tests can be difficult, tiring and overwhelming for autistic patients. They may worry as to whether they are responding correctly. Therefore, consider relying on objective tests such as retinoscopy or cover test more if the autistic patient appears to be distressed by subjective tests.

More generally, try to conduct demanding tests early in the examination where possible. Reassure autistic patients that they can ask questions at any point during the examination and offer optional breaks, especially after demanding tests.

Tips for dispensing staff

1. Give autistic patients time and space to choose new spectacle frames

Unless assistance is sought, avoid constantly watching or hovering around autistic patients when they are selecting new spectacle frames, which can make them feel anxious. Give autistic patients the option to return another day to arrange their new spectacles. This would be particularly useful if they feel tired or overwhelmed following the eye examination.

2. Take a sequential approach to spectacle dispensing

Autistic patients can get overwhelmed with too much information at once. Therefore, go through the spectacle dispensing process in a step-by-step manner. Discuss lens choices, then spectacle frames and finally lens tints and coatings.

Key messages

Eye examinations can be challenging for autistic adults. Considerations need to be made concerning the whole practice visit, not just about what happens in the consulting room. Improving communication and adapting to patient needs are examples of good practice. Implementing these simple changes can easily reduce, if not overcome, many of the barriers to eye care services for autistic adults.

A round-up of the series

Research concerning the vision of autistic adults and their accessibility to eye care has been very limited. However, recently published research28, 29, 31 has filled these important gaps in understanding. The key outcomes of this work have been shared in this CPD series, where we have discussed:

- Autism and its key defining features

- Autistic sensory experiences

- The day-to-day impacts of visual sensory experiences for autistic people

- Optometric anomalies in autistic people

- Eye examination experiences of autistic adults and tips for improvement

- The importance of correct terminology in autism

- Easy-to-implement recommendations for autism-friendly eye care

Having a basic understanding of autism can allow us to appreciate the challenges and advantages an autistic person may face. This will subsequently, and importantly, influence how we support an autistic patient accessing our eye care services.

You can find out more about our research here: https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/autism-and-vision. This website also contains resources for autistic patients to help them prepare for an eye examination (which eye care providers can freely use), and recommendations for eye care providers for autism-friendly services as presented in this article.

- Dr Ketan Parmar is a research optometrist at Eurolens Research, and Optometry Clinical Tutor for the undergraduate Optometry degree programme at The University of Manchester.

References

- Kenny L, Hattersley C, Molins B, Buckley C, Povey C, Pellicano E. Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism. 2016;2(4):442-62.

- NICE. NICE style guide. 2019 [09/10/2022]; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd1/chapter/using-this-guide.

- National Autistic Society. How to talk and write about autism. 2022 [09/10/2022]; Available from: https://www.autism.org.uk/what-we-do/help-and-support/how-to-talk-about-autism.

- Autistica. Media Communications Guide. 2022 [09/10/2022]; Available from: https://www.autistica.org.uk/about-us/media-communications-guide.

- Elsabbagh M, Divan G, Koh YJ, Kim YS, Kauchali S, Marcín C, et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism research. 2012;5(3):160-79.

- Brugha T, Cooper S, McManus S, Purdon S, Smith J, Scott F, et al. Estimating the Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Conditions in Adults: Extending the 2007 Adult Psychiatric. 2012.

- Taylor B, Jick H, Maclaughlin D. Prevalence and incidence rates of autism in the UK: time trend from 2004-2010 in children aged 8 years. BMJ open. 2013;3(10):e003219-e.

- Hull L, Petrides KV, Mandy W. The Female Autism Phenotype and Camouflaging: a Narrative Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020;7(4):306-17.

- Kapp SK, Gillespie-Lynch K, Sherman LE, Hutman T. Deficit, difference, or both? Autism and neurodiversity. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(1):59-71.

- Hussein AM, Pellicano E, Crane L. Understanding and awareness of autism among Somali parents living in the United Kingdom. Autism. 2019;23(6):1408-18.

- Loomes R, Hull L, Mandy WPL. What Is the Male-to-Female Ratio in Autism Spectrum Disorder? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):466-74.

- Fombonne E. Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Paediatric Research. 2009;65(6):591.

- Lemmi V, Knapp M, Rahan I. The Autism Dividend. London: 2017

- Green D, Chandler S, Charman T, Simonoff E, Baird G. Brief report: DSM-5 sensory behaviours in children with and without an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(11):3597-606.

- Kientz M, Dunn W. A Comparison of the Performance of Children With and Without Autism on the Sensory Profile. The American journal of occupational therapy. 1997;51(7):530-7.

- Simmons D, Robertson A, McKay L, Toal E, McAleer P, Pollick F. Vision in autism spectrum disorders. Vision research. 2009;49(22):2705-39.

- Ben-Sasson A, Gal E, Fluss R, Katz-Zetler N, Cermak SA. Update of a Meta-analysis of Sensory Symptoms in ASD: A New Decade of Research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2019;49(12):4974-96.

- Crane L, Goddard L, Pring L. Sensory processing in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2009;13(3):215-28.

- Baum SH, Stevenson RA, Wallace MT. Behavioral, perceptual, and neural alterations in sensory and multisensory function in autism spectrum disorder. Progress in neurobiology. 2015;134:140-60.

- Clery H, Andersson F, Bonnet-Brilhault F, Philippe A, Wicker B, Gomot M. fMRI investigation of visual change detection in adults with autism. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2013;2:303-12.

- Beker S, Foxe JJ, Molholm S. Ripe for solution: Delayed development of multisensory processing in autism and its remediation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018;84:182-92.

- Marco EJ, Hinkley LB, Hill SS, Nagarajan SS. Sensory processing in autism: a review of neurophysiologic findings. Pediatric research. 2011;69(8):48-54.

- Robertson AE, Simmons DR. The Sensory Experiences of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Qualitative Analysis. Perception. 2015;44(5):569-86.

- Smith RS, Sharp J. Fascination and isolation: A grounded theory exploration of unusual sensory experiences in adults with Asperger syndrome. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2013;43(4):891-910.

- Anketell P, Saunders K, Gallagher S, Bailey C, Little J. Brief report: Vision in children with autism spectrum disorder: What should clinicians expect? Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2015;45(9):3041-7.

- Gowen E, Porter C, Baimbridge P, Hanratty K, Pelham J, Dickinson C. Optometric and orthoptic findings in autism: a review and guidelines for working effectively with autistic adult patients during an optometric examination. Optometry in Practice. 2017;18(3):145-54.

- Little JA. Vision in children with autism spectrum disorder: a critical review. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2018;101(4):504-13.

- Parmar KR. An investigation of optometric and orthoptic conditions in autistic adults. The University of Manchester: The University of Manchester; 2022.

- Parmar KR, Porter CS, Dickinson CM, Pelham J, Baimbridge P, Gowen E. Autism-friendly eyecare: Developing recommendations for service providers based on the experiences of autistic adults. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2022;42(4):675-93.

- England N. Accessible Information Standard – Overview 2017/2018. 2017.

- Parmar KR, Porter CS, Dickinson CM, Pelham J, Baimbridge P, Gowen E. Visual sensory experiences from the viewpoint of autistic adults. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12.